United/States: A Revolutionary History of American Statehood

Where did states come from? Almost everyone thinks that states descended immediately, originally, and directly from British colonies, while only afterward joining together as the United States. As a matter of legal history, that is incorrect. States and the United States were created by revolutionary independence, and they developed simultaneously in that context as improvised entities that were profoundly interdependent and mutually constitutive, rather than separate or sequential.

“States-first” histories have provided foundational support for past and present arguments favoring states’ rights and state sovereignty. This Article gathers preconstitutional evidence about state constitutions, American independence, and territorial boundaries to challenge that historical premise. The Article also chronicles how states-first histories became a dominant cultural narrative, emerging from factually misleading political debates during the Constitution’s ratification.

Accurate history matters. Dispelling myths about American statehood can change how modern lawyers think about federalism and constitutional law. This Article’s research weakens current support for “New Federalism” jurisprudence, associates states-rights arguments with periods of conspicuous racism, and exposes statehood’s functionality as an issue for political actors instead of constitutional adjudication. Flawed histories of statehood have been used for many doctrinal, political, and institutional purposes in the past. This Article hopes that modern readers might find their own use for accurate histories of statehood in the future.

Introduction

“Nations reel and stagger on their way; . . . they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things. And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all this, so far as the truth is ascertainable?”

—W.E.B. Du Bois1W.E. Burghardt Du Bois, Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880, at 714 (1935). Du Bois rejected historical theories from his era that simplified and distorted the recreation of American statehood and government after the Civil War. The political stakes of truth telling with respect to eighteenth-century statehood might be less urgent, yet Du Bois’s willingness to challenge intellectual orthodoxy has inspired many kinds of history, including this Article. See also Jill Lepore, This America: The Case for the Nation 10 (2019).

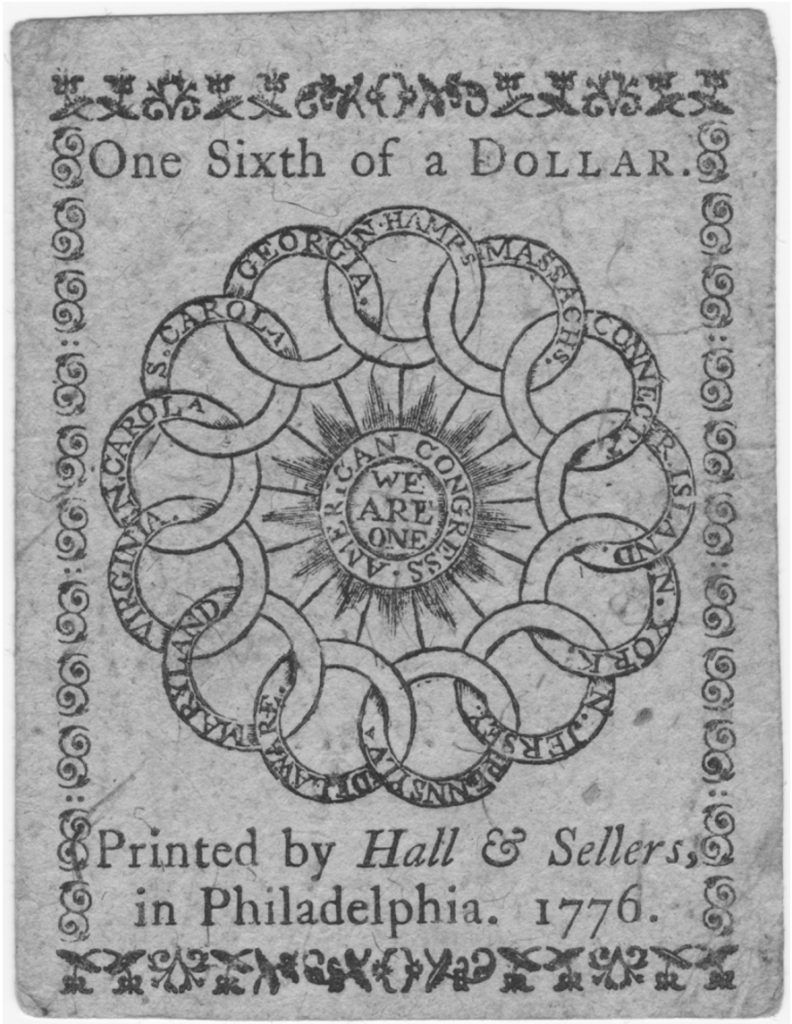

This Article starts with a fundamental question in legal history: where did states originally come from?2Two related questions will also need attention: What does the word “state” mean, and what time period should be used in describing where states “came from”? See infra Parts I, II. Two responses have been widely circulated, and even though one of them is very popular, both are dramatically flawed. The popular “states-first” answer is that states historically preceded all forms of interstate government. Thirteen British colonies reopened as thirteen American states under “New Management” signs, and those entities fit together like colored pieces of a map-shaped puzzle.3Eighteenth-century maps looked very different from modern puzzles. See, e.g., Carington Bowles, Bowles’s New Pocket Map of the United States of America; the British Possessions of Canada, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland, with French and Spanish Territories of Louisiana and Florida, as Settled by the Preliminary Articles of Peace Signed at Versailles the 20th. of Jany. 1783 (1784), https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3700.ar074500/ [https://perma.cc/C568-EF2B]. See also Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States 7–12, 74–75, 221–23, 343–44 (2019). For efforts to trivialize the eighteenth-century transition from colonies to states, see Thomas Jefferson, The Article on the United States in the Encyclopédie Méthodique (Jan. 24, 1786), reprinted in 10 The Papers of Thomas Jefferson 3, 11–12 (Julian P. Boyd et al. eds., 1954), and Allan Nevins, The American States During and After the Revolution, 1775-1789, at 1 (1924). Historians, lawyers, and schoolchildren rely on states-first histories whenever they say that “states came together” to form the United States.4Gordon S. Wood, Federalism from the Bottom Up, 78 U. Chi. L. Rev. 705, 724 (2011) (book review) (stating that, under the Articles of Confederation, “[t]hirteen independent and sovereign states came together to form a treaty”); see also, e.g., David C. Hendrickson, Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding (Wilson Carey McWilliams & Lance Banning eds., 2003); Michael J. Klarman, The Framers’ Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution 14 (2016); Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788, at 17 (2010); Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution 163 (1996); Akhil Reed Amar, The David C. Baum Lecture: Abraham Lincoln and the American Union, 2001 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1109, 1124. According to standard historical narratives, states emerged first—as the essential and primary entities of American law and territory—while the United States arrived later as a derivative project.

The unpopular “union-first” answer is that statehood was secondary because the legal category itself was conceived and implemented through interstate government.5An even less popular alternative was once sketched by Willi Paul Adams, The First American Constitutions: Republican Ideology and the Making of the State Constitutions in the Revolutionary Era (Rita Kimber & Robert Kimber trans., 1980). For criticism of Adams, see Jack N. Rakove, Book Review, 38 Wm. & Mary Q. 297, 297–301 (1981). Abraham Lincoln proclaimed that “[t]he Union is older than any of the States; and, in fact, it created them as States. Originally, some dependent colonies made the Union; and, in turn, the Union threw off their old dependence . . . and made them States, such as they are.”6Abraham Lincoln, Special Session Address (July 4, 1861), reprinted in 4 The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln 421, 433–35 (Roy P. Basler ed., 1953). A generation earlier, Andrew Jackson roared that “[t]he unity of our political character . . . commenced with its very existence.”7Proclamation No. 26, Respecting the Nullifying Laws of South Carolina (Dec. 10, 1832), reprinted in 11 Stat. 771, 777 (1859). The United States predated its component parts because “[u]nder the royal government we had no separate character; our opposition to its oppressions began as United Colonies. We were the United States under the confederation, and the name was perpetuated . . . . In none of these stages did we consider ourselves in any other light than as forming one nation.”8Id.

One eighteenth-century eyewitness, James Wilson, ridiculed any historical argument that states were independent of interstate government: “It is objected . . . that under [the Constitution] there is no sovereignty left in the state governments. . . . but I should be very glad to know at what period the state governments became possessed of the supreme power.”9Remarks of James Wilson in the Pennsylvania Convention to Ratify the Constitution of the United States, 1787, in 1 Collected Works of James Wilson 258 (Dec. 11, 1787) (Kermit L. Hall & Mark David Hall eds., 2007) (emphasis added); see id. at 201 (Dec. 1, 1787); Remarks by James Wilson at the Debates in the Convention of the State of Pennsylvania on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (Dec. 1, 1787), in 2 The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787, at 443 (Jonathan Elliot ed., Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott Co. reprt. 2d ed. 1937) (1836) [hereinafter State Conventions (1836)]. Wilson presciently warned that, when Americans do not understand the true history of statehood, discussions collapse into “a mere illusion of names. We talk of states, till we forget what they are composed of.”10Remarks by James Wilson at the Debates in the Convention of the State of Pennsylvania on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (June 30, 1787), in 5 Debates on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution in the Convention Held at Philadelphia, in 1787; with a Diary of the Debates of the Congress of the Confederation 261, 262 (Jonathan Elliot ed., Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott Co. 1845) [hereinafter State Conventions (1845)] (emphasis added). Even though prominent historical figures like Lincoln, Jackson, and Wilson all argued that the United States came first—with states emerging afterward as legal subordinates—almost no one believes that today.11See Amar, supra note 4, at 1124 (rejecting Lincoln’s approach). But see Richard B. Morris, The Forging of the Union Reconsidered: A Historical Refutation of State Sovereignty over Seabeds, 74 Colum. L. Rev. 1056, 1056, 1089 (1974) (arguing incorrectly that states were “a creation of the Continental Congress, which preceded them in time and brought them into being”); Garry Wills, Inventing America: Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, at ix (1978) (adopting Morris’s thesis after once having denied it).

This Article rejects both theories, which have been endlessly repeated in American politics and law. Advocates have used states-first and union-first histories to debate the Alien and Sedition Act in the eighteenth century, state nullification of nineteenth-century tariffs, secession during the Civil War, and twentieth-century resistance to racial desegregation.12For states-first arguments against the Alien and Sedition Act, see Thomas Jefferson, Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 and 1799, reprinted in 4 State Conventions (1836), supra note 9, at 540–44. For states-first arguments that favor tariff nullification, see South Carolina, Ordinance to Nullify an Act of the Congress of the United States, entitled “An Act Further to Provide for the Collection of Duties on Imports,” Commonly Called the Force Bill (Mar. 18, 1833), reprinted in Journal of the Convention of the People of South Carolina 129–30 (Columbia, S.C., R.W. Gibbes 1833), and 9 Reg. Deb. 364 (1833).

For secession and the Civil War, see Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union (1860), reprinted in John Amasa May & Joan Reynolds Faunt, South Carolina Secedes 76, 76–81 (1960), and 1 Alexander H. Stephens, A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States 370 (Philadelphia, Nat’l Publ’g Co. 1868).

For twentieth-century racial segregation, see James Jackson Kilpatrick, The Sovereign States: Notes of a Citizen of Virginia 258–63 (1957). Other prominent applications of states-first history include Franklin Pierce, Veto Message on Legislation Funding Public Works (Aug. 4, 1854), in 6 A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents 2789, 2789–90 (James D. Richardson ed., New York, Bureau of Nat’l Literature 1897), and Letter from Sec’y of State Thomas Jefferson to President George Washington (Mar. 18, 1792), http://jeffersonswest.unl.edu/archive/view_doc.php?id=jef.00105 [https://perma.cc/S4WN-U86M].

As we have seen, Lincoln and Jackson advanced union-first histories in their opposition to nullification and secession. See supra notes 6–7 and accompanying text. Lincoln further claimed that “[o]ur States have neither more, nor less power, than that reserved to them, in the Union, by the Constitution—no one of them ever having been a State out of the Union.” Lincoln, supra note 6, at 433. If Lincoln’s theory were deemed legally acceptable, then all originalist analysis of statehood should focus exclusively on the late 1780s, regardless of earlier historical evidence about independence and confederation. See Part III (describing unresolved debates over statehood during the 1780s). For an exaggerated vision of preconstitutional unity after Lincoln’s death, see Charles Sumner, Address Before the New York Men’s Republican Union: Are We a Nation? 11 (Nov. 19, 1867) (transcript on file with the Michigan Law Review). Supreme Court cases have cited states-first history to support slavery under Dred Scott, modern doctrines of “freestanding federalism,” and many other legal results.13For academic discussion of “freestanding federalism,” see infra Section IV.A; John F. Manning, Federalism and the Generality Problem in Constitutional Interpretation, 122 Harv. L. Rev. 2003 (2009); Gillian E. Metzger, The Constitutional Legitimacy of Freestanding Federalism, 122 Harv. L. Rev. F. 98 (2009); see also Craig Green, Erie and Problems of Constitutional Structure, 96 Calif. L. Rev. 661 (2008); Henry Paul Monaghan, Supremacy Clause Textualism, 110 Colum. L. Rev. 731 (2010).

For sixteen examples when the Supreme Court has invoked states-first history, see Federal Maritime Commission v. South Carolina State Ports Authority, 535 U.S. 743, 752 (2002); Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898, 918–19 (1997); United States Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779, 802–03 (1995) (quoting Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1, 9 (1964)); Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452, 457 (1991); Blatchford v. Native Village of Noatak, 501 U.S. 775, 779 (1991); Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1, 16, 18 (1890); Texas v. White, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 700, 725 (1868), overruled in part by Morgan v. United States, 113 U.S. 476 (1885); Jackson v. The Steamboat Magnolia, 61 U.S. (20 How.) 296, 323 (1857) (Campbell, J., dissenting); Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393, 434 (1857); Thurlow v. Massachusetts, 46 U.S. (5 How.) 504, 587 (1847), overruled in part by Leisy v. Hardin, 135 U.S. 100 (1890); Martin v. Lessee of Waddell, 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 367, 410 (1842); Rhode Island v. Massachusetts, 37 U.S. (12 Pet.) 657, 693 (1838); Sturges v. Crowninshield, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 122, 192–93 (1819); and Ware v. Hylton, 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 199, 224 (1796) (Chase, J.). See also Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U.S. 238, 295–96 (1936). The Supreme Court has issued very few examples of “union-first” history. See United States v. Curtiss-Wright Exp. Corp., 299 U.S. 304, 317 (1936). Only one Supreme Court opinion points toward a third possibility that has the benefit of being, perhaps inadvertently, historically accurate. See Lane County v. Oregon, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 71, 76 (1868) (“Both the States and the United States existed before the Constitution.”). In 2019, the Supreme Court declared that “[a]fter independence, the States considered themselves fully sovereign nations,” and it concluded that therefore “the States retain their sovereign immunity” up to the present.14See Franchise Tax Bd. v. Hyatt, 139 S. Ct. 1485, 1493, 1498 (2019). An earlier opinion from Justice Breyer contradicted the approach in Hyatt, despite Breyer’s own casualness about underlying historical facts. “The original 13 States, once dependents of Britain, became independent entities perhaps at the time of the Declaration of Independence [1776], perhaps at the signing of the Treaty of Paris [1783], perhaps with the creation of the Articles of Confederation [1781]. (I need not be precise.)” Puerto Rico v. Sanchez Valle, 136 S. Ct. 1863, 1878 (2016) (Breyer, J., dissenting). Using states-first history to overturn a forty-year-old precedent, the Court confirmed that the legal status of eighteenth-century statehood remains important today—at least in some contexts and for some audiences.15Hyatt, 139 S. Ct. at 1493, 1499 (overturning Nevada v. Hall, 440 U.S. 410 (1979)).

Despite widespread disputes, no one has written an adequate history of legal statehood.16Peter Onuf’s attention to the historical construction of statehood is a partial counterexample, but his conclusions remain deeply affected by states-first assumptions. See Peter S. Onuf, The Origins of the Federal Republic: Jurisdictional Controversies in the United States, 1775–1787 (1983); Peter S. Onuf, State-Making in Revolutionary America: Independent Vermont as a Case Study, 67 J. Am. Hist. 797 (1981); see also Peter S. Onuf, Statehood and Union: A History of the Northwest Ordinance (1987); Peter S. Onuf, Jefferson’s Empire: The Language of American Nationhood (2000). By contrast, analysis by German scholar Willi Paul Adams offers a useful complement or corrective to existing historical narratives. See Adams, supra note 5. The American public has ignored basic questions about how and when statehood developed, perhaps assuming that states arrived along with sailors’ luggage or developed through some kind of natural evolution. Most scholars have likewise presumed that the status of American states was essentially constant from 1776 to 1788, thereby drawing artificially straight lines from colonial status to constitutional statehood.17See, e.g., Nevins, supra note 3, at 1. Civics-class mythology has obscured the historical meaning of eighteenth-century statehood, and it has also distorted efforts to understand how states became what they are today.

To begin with obvious errors, it was impossible for thirteen British colonies to become thirteen American states because only twelve colonies joined the Revolution. The thirteenth state, called by its new name “Delaware,” spent nearly a century as the “Lower Counties” of Pennsylvania, and colonists in that region claimed independence from William Penn and Britain at precisely the same time. Some readers will be shocked to hear that there never was a British colony “Delaware.”18One could collect thousands of inaccurate references to “thirteen” rebellious British colonies. Every generation of citizens, lawyers, and scholars has accepted that number as the unquestioned truth. E.g., Robert J. Allison, The American Revolution: A Very Short Introduction 4, 19 (2015). But the analytical point runs much deeper than any simple factual correction. Every popular history of statehood appears more supportable if one assumes that there were thirteen colonies, and so do conventional histories of Delaware and triumphal myths about the Constitution.19E.g., Akhil Reed Amar, America’s Constitution: A Biography 247 (2005) (claiming that Delaware was omitted from a 1776 version of Benjamin Franklin’s snake cartoon “Join, or Die” because Franklin came from Pennsylvania). In fact, Benjamin Franklin was quite familiar with the Lower Counties’ status as a semiautonomous entity inside Pennsylvania, having published the first copy of the Laws of the Government of New Castle, Kent, and Sussex [Counties] upon Delaware in 1741, and having also printed currency for the Lower Counties’ government. See The Earliest Printed Laws of Delaware 1704–1741, at 12 (John D. Cushing ed., 1978); Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin 125 (Leonard W. Labaree et al. eds., 2d ed. 1964). For orthodox Delawarean history, see John A. Munroe, History of Delaware 63 (5th ed. 2006) [hereinafter Munroe, History of Delaware], and John A. Munroe, Colonial Delaware: A History 217–34 (Delaware Heritage Press 2003) (1978) [hereinafter Munroe, Colonial Delaware]. Perhaps Amar deserves credit as one of the only law professors to notice anything at all odd about Delaware during the revolutionary period. This Article suggests that dominant narratives about statehood have repeatedly ignored awkward details. Correcting historical narratives is one step toward fixing constitutional law. With respect to American statehood, inattention to Delaware dramatically illustrates how far there is to go.

Twelve other revolutionary states used prerevolutionary colonial names, which verbally announced new entities’ existence and the old regime’s annihilation.20Similar tactics about governmental names appear among modern postrevolutionary governments as well. See 1 Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes, at xv–xvi (Neil J. Kritz ed., 1995). The act of claiming those names was politically important, yet the new states “Virginia” and “New York” were legally different from the colonies that came before. The Revolution altered legal definitions of state citizenries, officials, and institutions, while also transforming boundaries that defined the states themselves.21See Daniel J. Hulsebosch, The Revolutionary Portfolio: Constitution-Making and the Wider World in the American Revolution, 47 Suffolk L. Rev. 759, 776 (2014) (“[E]ach state prosecuted native-born or long-domiciled residents who remained loyal to the Empire as traitors. Treason prosecutions, by judicial verdict and statutory attainder, also became an important source of revenue for the states.”); Alan Taylor, Expand or Die: The Revolution’s New Empire, 74 Wm. & Mary Q. 619, 630 (2017) (“We often overlook the enhancement of state power because of our preoccupation with a national story focused on the federal Union.”). For centuries, British imperial law created and sustained colonies as territorial entities. The renunciation of British law produced a new category of “statehood” that reflected an aspirationally emerging legal order.

Prerevolutionary colonies were supposed to be formally subservient, malleable, and derivative creations of the British Empire.22Colonial experience did not always follow such a rigid hierarchy in practice. See Jack P. Greene, The Quest for Power: The Lower Houses of Assembly in the Southern Royal Colonies 1689-1776, at 3–4 (1963). American states had different objectives—a major impetus for the Revolution—and no state acted alone in creating or pursuing its augmented legal status. States did not rise onto naturally independent feet. Nor did interstate negotiations resemble international diplomacy where background norms about negotiators’ legal status and territorial existence were taken for granted.23Dan Hulsebosch and David Golove have shown that diplomacy and the law of nations were essential components of eighteenth-century statehood, as they also were essential to the United States’ emergent nationhood. See David M. Golove & Daniel J. Hulsebosch, A Civilized Nation: The Early American Constitution, the Law of Nations, and the Pursuit of International Recognition, 85 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 932, 935, 980 (2010) (describing “The International Constitution”); Daniel J. Hulsebosch, Being Seen Like a State: How Americans (and Britons) Built the Constitutional Infrastructure of a Developing Nation, 59 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1239, 1242–46 (2018) (adding international commerce and credit to analysis of governmental structures); Hulsebosch, supra note 21, at 769 (“[R]evolutionary institution-building was performed on an international stage.”); see also Eliga H. Gould, Among the Powers of the Earth: The American Revolution and the Making of a New World Empire (2012) (describing the United States’ emphasis on international reputation). Although such works have sometimes analogized early statehood to an international treaty among sovereign European governments, they also acknowledge that “the political relationships among the states and between each state and the Congress were left unmapped,” Golove & Hulsebosch, supra at 951, which illustrates a fundamental difference between American statehood and most examples from European history. See Daniel J. Hulsebosch, Constituting Empire: New York and the Transformation of Constitutionalism in the Atlantic World, 1664–1830, at 189 (2005) (“Throughout the war, the relationship between the state and the Continental Congress, and then Confederation government, was unclear.”); Hulsebosch, supra note 21, at 774 (“There was . . . no internationally prescribed mode for gaining recognition as an independent state.”); cf. Hulsebosch, supra at 170 (“We have a government, you know, to form; and God only knows what it will resemble.” (quoting a letter from John Jay on July 6, 1776)).

Other research has shown that negotiations with and violence against Native Americans are frequently overlooked aspects of revolutionary and constitutional statehood. Gregory Ablavsky, The Savage Constitution, 63 Duke L.J. 999, 999 (2014); Craig Green, Creating American Boundaries: Federalism and Dispossession (unpublished manuscript) (on file with author). Even though this Article will focus on the development of legal materials by white North Americans, no one should assume that such episodes were ever fully isolated from European and Native American forms of power, law, or influence.

On the contrary, legal characteristics of American states and statehood were created and negotiated in the same historical moments as the United States’ central government, often through the same legal documents. States and the United States repeatedly leaned on one another for support and recognition, operating and functioning together, of necessity and also by design. Both layers of government jointly manufactured structures to organize populations and territory even as they struggled with one another over particular substantive points. American law borrowed heavily from British experience in other regards,24See 1 William E. Nelson, The Common Law in Colonial America: The Chesapeake and New England, 1607–1660 (2008); 2 William E. Nelson, The Common Law in Colonial America: The Middle Colonies and the Carolinas, 1660–1730 (2013). but establishing the status of states and their relationship to central government would require substantial innovation and improvisation.

American statehood was never determined by abstract theory, nor was it produced by facile imitation. To ask which came first as a historical matter—the states or the United States—yields a paradox of chickens and eggs that is widely overlooked. Exploring that paradox raises deeper questions about what statehood originally meant and how states developed in the centuries that followed. This Article analyzes in detail the former issue of origins, while highlighting later historical developments as an important topic for future research.25See Alison L. LaCroix, The Interbellum Constitution: Union, Commerce, and Slavery from the Long Founding Moment to the Civil War (forthcoming 2020); Maeve Glass, Founding Properties (unpublished manuscript) (on file with author).

American states were not easily derived from British colonies, just as the United States did not simply recreate the British Empire. Hundreds of books have analyzed how the national United States displaced British North America, yet almost no scholarship has considered how states displaced colonies.26E.g., Jack P. Greene, The Constitutional Origins of the American Revolution (2011). This Article’s history of statehood is distinct from abundant histories of federalism, though it obviously borrows from that literature. Histories of federalism typically cover different subjects and use different source materials that bypass the origins of states, while shifting attention toward the integration, separation, and interrelationship of such entities relative to the United States. Compare Alison L. LaCroix, The Ideological Origins of American Federalism (2011), and David Brian Robertson, Federalism and the Making of America (2d ed. 2018), with infra Part I. To understand statehood as a legal category requires new interpretations of the Revolution and the Constitution. It also raises questions about history’s practical significance when modern courts interpret and apply constitutional law.

This Article proceeds in four steps. Part I explains what it means to study states and statehood as objects of legal history. Comparable to “cities,” “colonies,” “corporations,” and “nations,” states and statehood are technical legal entities that only sometimes overlap with nonlegal experience.27For example, one could define a “city” based on particular standards for high-density residence, aggregations of urban infrastructure, or cultural features like television channels and sports teams. See Jean Gottmann, Megalopolis: The Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the United States 24 (1961) (defining a New York-centered urban area based on sociological concentrations of population, “banking, insurance, wholesale, entertainment and transportation activities”). From a strictly legal perspective, however, cities are formal entities that possess technically prescribed borders, governments, origins, powers, and responsibilities. Hendrik Hartog, Public Property and Private Power: The Corporation of the City of New York in American Law, 1730–1870, at 2 (Cornell Univ. Press 1989) (1983). One could similarly use the word “corporation” to describe almost any powerful aggregation of wealth or personnel—as in “corporate America”—or the term could be reserved for a specific kind of legally chartered entity with prescribed legal powers and a technical residence. Cf. James Wilson, Address to the People of Philadelphia, Speech Delivered at the Pennsylvania Ratifying Convention (Oct. 6, 1787), https://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/1787-wilson-address-to-the-people-of-philadelphia-speech [https://perma.cc/98YU-3SSV] (“In common parlance, indeed, [the word ‘corporation’] is generally applied to petty associations for the ease and conveniency of a few individuals; but in its enlarged sense, it will comprehend the government of Pennsylvania, the existing union of the states, and even [the proposed Constitution] . . . .”). A few scholars have analyzed states as economic, social, intellectual, or cultural entities, and their research has focused on economic, social, intellectual, and cultural materials.28Some of the best scholarship in this group has described economic, social, intellectual, and cultural forces that transcend or challenge the limits of statehood and nationhood. See Contested Spaces of Early America (Juliana Barr & Edward Countryman eds., 2014); Mary Sarah Bilder, The Transatlantic Constitution: Colonial Legal Culture and the Empire (2004); Charles S. Maier, Once Within Borders: Territories of Power, Wealth, and Belonging Since 1500 (2016). By contrast, this Article offers an “unapologetically” legal history of statehood, which is tightly focused on legal documents and negotiations without addressing broader relationships to economic practice, social reality, intellectual theory, or cultural characterization.29Hendrik Hartog, Man and Wife in America: A History 2 (2000) (describing the potential importance of focused legal history, despite its clear imperfections). Such legally oriented analysis cannot be the last word on the history of states and statehood, but perhaps it will provide a useful step forward.

Part II presents three kinds of evidence from 1775 to 1788 about the origins and nature of statehood. One category involves the first American constitutions, which effectively inaugurated provincial government outside of British authority. From their earliest existence, breakaway colonies-and-states were not manufacturing constitutions in their capacity as self-authorized sovereignties, standing alone and boldly announcing their existence. On the contrary, provincial constitutional systems were requested by, coordinated with, and validated through the Continental Congress as an aspirationally central government.

A second category of evidence surrounds declarations of independence that rejected British authority to formally produce anticolonial statehood. Revolutionary colonies and states asserted legal independence from Britain through highly interdependent mechanisms, analogous to state and central cooperation in the contemporaneous war that they were trying to survive. There was never any historical moment when states could have preceded the United States because both layers of government were interrelated in their joint and codependent legal struggles for existence. From the beginning, states and the United States had to function together, and their developing legal status reflected that interlocking set of needs.

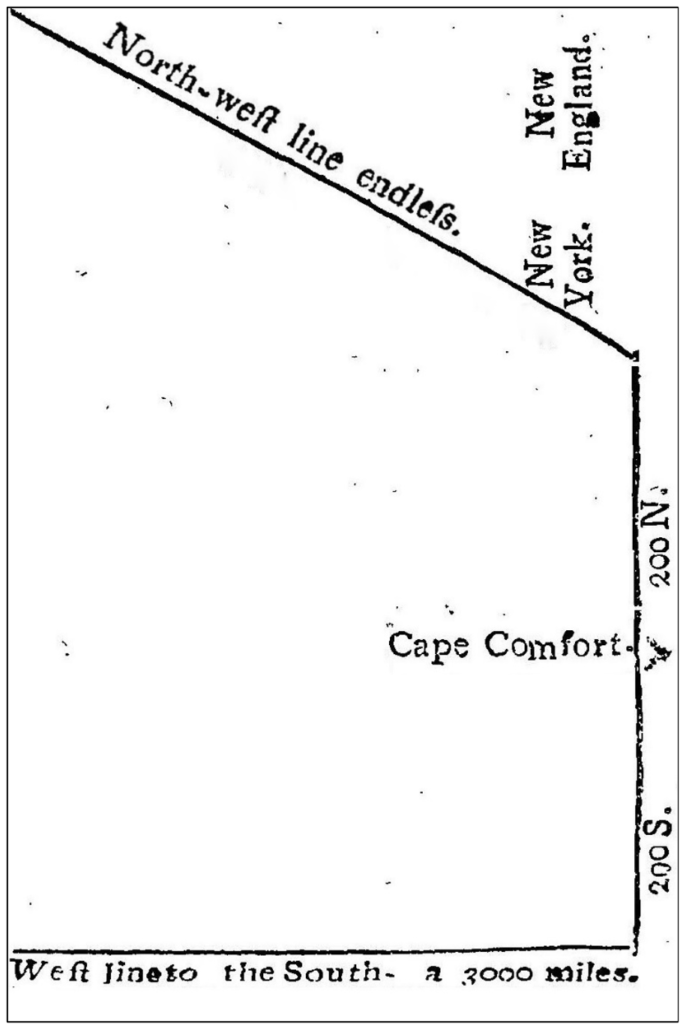

The third category involves states as territorial entities with geographically specific borders, authorities, and responsibilities. Renouncing British imperial government implied that states and central governments had to decide for themselves—and alongside one another—how territorial claims could be asserted and challenged. Legal borders defined where states were located, and those decisions determined states’ economic and demographic future, while also establishing a framework for states to exist and coexist.

All of these eighteenth-century materials indicate that states were very different from colonies. They were also different from international countries like France, as well as existing confederacies like the Netherlands or the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee). Revolutionary states were never independent from one another, much less were they autonomous from the interstate governments that they helped to inaugurate. American “States” were always “United,” and those words were repeatedly contested and constructed in the same historical episodes.

As an ancillary project, Part III examines the origins of inaccurate myths about preconstitutional states and statehood. States-first and union-first arguments have served diverse political purposes throughout United States history, including the Constitution’s framing and ratification. This Article’s thesis is that such theories were always developed and contested, rather than timeless, original, or conventional. During eighteenth-century ratification debates, for example, Federalists and Anti-Federalists disagreed about the Constitution’s substantive merit. Yet both sides circulated broken histories of the Articles of Confederation, characterizing states as primary, essential, and sovereign in contrast to the weak and derivative central government. After ratification, similarly distorted images of preconstitutional state-centrism were even more prominent. Modern intellectuals and lawyers cannot hope to escape this flawed consensus unless they look beyond Federalist and Anti-Federalist pamphlets. Reliance on that deeply political literature explains many Americans’ orthodox misimpression that somehow—in the beginning—there were states.

Part IV briefly considers possible normative implications. Supreme Court decisions espousing “freestanding federalism” have relied on abstract intuitions about eighteenth-century history without attention to factual details. Although this Article will not address specific doctrinal questions, it rejects any assumption that constitutional statehood was a primordial fact or an eighteenth-century consensus. States did not enter the union fully formed of their own volition. Under such circumstances, states could not legally rely on implicit assumptions about their new constitutional status—they had to depend on postratification politics. In the late eighteenth century, statehood was not a background convention that simply went without saying. It was a contested legal category that changed several times, with some aspects explicitly resolved, and many questions persistently unanswered.

As with the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution did not simply diminish states by making them compromise preexisting status and authority; it also established state powers that were previously lacking. Contrary to popular myths, states did not give up one fraction of their natural sovereignty to silently preserve the rest. Instead, the Constitution composed and reformed statehood itself as a legal category, revising and borrowing from earlier models, clarifying some issues while leaving others undecided. Most modern doctrines that affirm and establish states’ rights cannot be credibly planted in the shifting sands of eighteenth-century statehood. Right or wrong, today’s states-rights advocates must seek constitutional support from other historical periods and materials.

Historical mistakes have allowed modern conventions about states’ rights to slip backward in time, from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries toward an undifferentiated period of 1776 to 1788. There were plenty of states-rights arguments during ratification, and those positions gained more power as the United States’ economic and legal systems developed. The problem is that rewritten timelines can help states-rights advocates to insulate arguments about constitutional statehood from the politics of later periods, including massive plantation slavery and Jim Crow racism. This Article challenges a phenomenon that could be called “Founders-Chic Federalism” in order to clarify the specific history of states-rights doctrines, while also inviting closer attention to the use of historical arguments elsewhere in constitutional law.30See Francis D. Cogliano, Founders Chic, 90 History 411, 412 n.2 (2005) (book review); David Waldstreicher, Founders Chic as Culture War, 84 Radical Hist. Rev. 185 (2002). For one especially sophisticated example of “Founders Chic” scholarship, see Joseph J. Ellis, American Dialogue: The Founders and Us 7–9 (2018) (“Given our current condition as a deeply divided people, my hope is that the founding era can become a safe space to gather together, not so much to find answers to . . . questions as to argue about them.”); id. at 223–24 (“Soon after their departure, a thick cloud of incense formed around the founders . . . . The founders desperately wanted to be remembered. But they must not be canonized.”).

Enthusiasm for historical accuracy depends on a broad legal audience more than any particular author.31See supra note 1 and accompanying text (quoting W.E.B. Du Bois concerning the “Propaganda of History”). This Article may convince some readers that constitutional law demands more careful and accurate historical analysis. Other readers might think that constitutional law should make fewer substantive claims based on casual historical characterizations. Insofar as modern federalism doctrine is serious about eighteenth-century history, the consequences of this Article’s revisionism are substantial and obvious. By contrast, if modern uses of eighteenth-century history are simply ornamental, lawyers must acknowledge that constitutional statehood has changed over the years, despite prevalent rhetoric about timeless consistency. Under either scenario—historical instability in the eighteenth century or doctrinal instability afterward—this Article proposes that most issues concerning statehood should be presumptively decided by modern political instruments instead of constitutional adjudication. The latter institutional mechanisms rely too often on unfortunate mixtures of flawed eighteenth-century history and misplaced twenty-first-century functionalism. Some aspects of statehood were constitutionally specified, including the Electoral College, allocation of Senate seats, and territorial boundaries. Yet most details remain open for political debate and disposition, as was also true in the beginning.

I. Analyzing States as Legal Entities

The time period between the Revolution and the Constitution is one of the most widely studied in United States history, yet almost no one has analyzed eighteenth-century states as legal entities. This Part briefly explains this Article’s relationship to two general categories of existing scholarship. The first category tends to highlight national development of the United States and constitutional federalism without analyzing the revolutionary origins, contours, and composition of statehood.32See Amar, supra note 19, at 122; Klarman, supra note 4, at 5; Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787, at 355–56 (1969). Such nationalist scholarship of federalism centers on the allocation of powers to central governments as though states already existed as fully formed elements of the constitutional system.33See George William Van Cleve, We Have Not a Government: The Articles of Confederation and the Road to the Constitution 3–7 (2017). Many political theorists have produced blueprints about American nationhood and federalism that portray states as mostly inert or unexamined entities until the ratification debates.34See Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution 25–32, 324–37 (enlarged ed. 1992); Maier, supra note 4, at 126. There are many histories that involve states without providing histories of statehood. Even as the legal shift from Britain to America has received extraordinary attention, the legal shift from colony to state has not had nearly enough.

A second set of research has considered individual states in isolation, typically beginning with European ships and colonial charters long before states or statehood were even imagined.35See, e.g., Jere R. Daniell, Colonial New Hampshire: A History 14–22 (Univ. Press of New Eng. 2015) (1981); Munroe, Colonial Delaware, supra note 19, at 15; Peter Wallenstein, Cradle of America: A History of Virginia 1–5 (2d rev. ed. 2014). Law is rarely central to these provincial histories, and the law of statehood never is.36Cf. Howard Pashman, Building a Revolutionary State: The Legal Transformation of New York, 1776–1783, at 20–21 (2018) (discussing the transformation of private law alongside revolutionary politics, without directly analyzing statehood as a legal category). On the contrary, the point is to describe an imaginary or essential entity whose history transcends formal categories of colonies or statehood. Provincial histories often describe cultural, religious, economic, and social dynamics in order to understand how particular groups of people gathered and organized themselves in places called “Virginia” or “Massachusetts.”37See, e.g., Marsha L. Hamilton, Social and Economic Networks in Early Massachusetts: Atlantic Connections 8–15 (2009). Less attention is paid to a state’s peers in different locations, and very little is given to the legal category that defined the peership itself. Provincial histories often culminate in stories about the United States, thus resembling the first category of nationalist scholarship.38See supra notes 32–34 and accompanying text. In other respects, however, most research about particular states could just as easily describe British Quebec, New Spain, and East or West Florida, which never became individual states at all.39Similar historical treatment is common for territorial governments outside the United States. For example, James Kennedy’s analysis of the Netherlands explicitly considers “historical developments within the territory that at present constitutes the Kingdom of the Netherlands.” James C. Kennedy, A Concise History of the Netherlands 3 (2017). The first chapter starts 15,000 years ago with groups whose lived experiences had no connection to modern ideas about “the Netherlands” as such. See id. at 10–11. The point is not to criticize Kennedy’s approach—much less provincial scholarship concerning individual states—but rather to identify potentially variable starting points for any history of the Netherlands, Virginia, or the United States. With the land or first residents, with any self-identified polity, or with the first government to use the modern name? This Article will focus exclusively on legal history, but certainly that is just one way—with benefits and costs—to analyze such complicated questions. For current purposes, such provincial histories often include descriptions of particular states without exploring the category of statehood.

This Article highlights states and statehood by identifying when and how states came into being, separate and apart from colonial entities that—aside from Delaware—operated for a long time under the same names. Such close attention to preconstitutional statehood sets an important baseline for identifying what states originally meant and how they developed in the revolutionary period. Unlike most scholarship, this Article’s source materials are not especially ideological—focused on ageless philosophers or theorists—nor are they especially materialist—focused on allocations of human bodies and property. Instead, the ambition is to implement a mezzanine-level history of legal statehood that focuses on how aspirationally legal ideas were expressed in operative documents and negotiations.40Attempts to define “law” and “legal” can be especially complex in discussions that involve historical materials. See 1 G. Edward White, Law in American History: From the Colonial Years Through the Civil War 1–15 (2012); see also Sally Falk Moore, Law and Social Change: The Semi-Autonomous Social Field as an Appropriate Subject of Study, 7 Law & Soc’y Rev. 719, 719–20 (1973); Hendrik Hartog, Snakes in Ireland: A Conversation with Willard Hurst, 12 Law & Hist. Rev. 370, 377–78 (1994). Instead of offering analytical theories of what law is today, much less what it was for these historical actors, this Article will narrowly focus on groups of legal materials that should be easily recognizable as such in the modern era and would be similarly recognizable to Anglo-Americans in the eighteenth century. Erudite arguments that all Eurocentric law conceptually derived from Roman history presents a cautionary tale against trying to elaborate similar themes in this Article. See Aldo Schiavone, The Invention of Law in the West (Jeremy Carden & Antony Shugaar trans., 2012).

This Article’s methodology assumes that groups of disgruntled colonists were tied to one another by something more than unvarnished economics, religion, and social factors. They were also bound together by law, and those legal documents were not identical to political propaganda or European intellectualism. This Article emphasizes revolutionary Americans who started to produce, manage, and serve collective entities that were self-consciously legal, including a peculiar mixture of American “states” that were “united” from the start.

Legal statehood deserves attention. Alongside familiar concepts of eighteenth-century liberty, equality, republicanism, and nationhood, the revolutionary period was also essentially concerned about “states.” None of the concepts on that list was a simple legacy from Britain, nor did any of them acquire singular meanings at specific moments thereafter.41See Alan Taylor, American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804, at 1–9 (2016); Daniel T. Rodgers, Republicanism: The Career of a Concept, 79 J. Am. Hist. 11, 11–38 (1992). Just like other revolutionary ideas, statehood exists dynamically among the fundamental “keywords, the metaphors, the self-evident truths” of American politics that matter “too deeply for us to use them in any but contested ways.”42Daniel T. Rodgers, Contested Truths: Keywords in American Politics Since Independence 16 (1998).

Statehood is already an implicitly fundamental feature of revolutionary history. Patriots did not fight simply to lower taxes, and military struggle is often a counterproductive way to reduce fiscal burdens.43See Justin du Rivage, Revolution Against Empire: Taxes, Politics, and the Origins of American Independence 5–23 (2017). At one level, colonists were essentially disputing what kinds of legal entities should tax and govern.44See James Otis, The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved (1764), reprinted in 1 Pamphlets of the American Revolution, 1750-1776, at 408 (Bernard Bailyn ed., 1965). Eighteenth-century revolutionaries argued that lawmakers and tax assessments should mostly derive from individual colonies or states, and sometimes from the United States.45Articles of Confederation of 1781, art. XIII (“[T]axes . . . shall be laid and levied by the authority and direction of the legislatures of the several States.”). Even though the British Empire made substantive governmental errors that the United States hoped to avoid, the Revolution’s most immediate and lasting guarantees concerned basic structures of leadership, government, and authority.46See Rivage, supra note 43, at 22. The operative legal entities after the war were declared to be states instead of colonies, and the United States instead of Britain. What any of those words meant in practice was up for grabs, and to understand what happened requires examining precisely when and how states emerged as legal entities.

II. Riddling About Chickens and Eggs

To explore the historical origins of legal statehood, this Part examines three sets of preconstitutional materials. First are efforts to create provincial governments through documents that were eventually called “state constitutions.” These represent the earliest efforts to announce new governmental structures that sought to establish—perhaps temporarily—states’ existence beyond British authority. Modern observers have viewed state constitutions as archetypically local episodes, and that characterization has made such documents especially important for states-first historians.47See 2 James Bryce, The American Commonwealth 22 (1888) (calling state constitutions “the oldest things in the political history of America”); see also Akhil Reed Amar, Of Sovereignty and Federalism, 96 Yale L.J. 1425, 1437–49 (1987). However, every state constitution—including the first examples in New Hampshire and South Carolina—emerged through the intimate cooperation and coordination of local authorities and the aspirationally Continental Congress. Revolutionary Americans established different levels of provincial and central governments improvisationally, in mutual reliance, and all at once. Neither states nor the United States could have plausibly claimed historical antecedence based on their legal actions, much less could either have claimed normative priority. Revolutionary politicians who were bracing for war did not have time to debate the theoretical chronology of chickens and eggs.

A second category of evidence involves efforts to identify “states” using that particular noun. Much like colonial status under the British Empire, the category of legal statehood was not something that happened through unexamined accidents. On the contrary, American statehood was claimed and contested at identifiable moments, including the Declaration of Independence’s description of the “United States” as “Free and Independent States.”48The Declaration of Independence (U.S. 1776). The Declaration of Independence itself was a formally collective document that recognized and created states as legally individual entities. A different declaration of statehood occurred in the same period, as a small revolutionary entity, the Lower Counties (modern Delaware), repudiated legal authority from Britain and Pennsylvania alike.49John A. Munroe, Revolution and Confederation, in 1 Delaware: A History of the First State 95, 106–07 (H. Clay Reed ed., 1947). Both the interstate Declaration of Independence and the Lower Counties’ provincial resolution emerged from complex legal relationships that represented indissoluble mixtures of state and interstate authority. Under every circumstance, declarations of legal independence from Britain created opportunities for debating what American states were supposed to be, and simultaneously how states were supposed to be organized inside the United States. Those two dynamics happened at the same time, with mutual interreliance and functional togetherness among various levels of government.

A third category of evidence involves states’ scope and existence as territorial entities. Many observers trivialize such issues under the misleading label “western lands,” but territorial law was more important than that.50See Peter Onuf, Toward Federalism: Virginia, Congress, and the Western Lands, 34 Wm. & Mary Q. 353, 353–56 (1977). One of a state’s earliest characteristics was its purported geographic location. Prerevolutionary and postrevolutionary states were legally identified by their connections to land, placing “Virginia” over here and “New York” over there.51But cf. John Mitchell, Thomas Kitchin & Andrew Millar, A map of the British and French Dominions in North America, with the Roads, Distances, Limits, and Extent of the Settlements, Humbly Inscribed to the Right Honourable the Earl of Halifax, and the Other Right Honourable the Lords Commissioners for Trade & Plantations (1755), https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3300.np000009/ [https://perma.cc/NRP3-E4TK] (depicting Virginia and New York with the same color and thus inseparably blending each into one another). Before the Revolution, some colonial borders were vague, and their location seemed purely theoretical with respect to areas that Europeans seldom visited.52See Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815, at xxv–xxxii (20th anniversary ed. 2011) (indicating how territorial and other intercultural disputes were changed by more solid legal institutions and more aggressive European migration).

As a matter of legal status, Britain always possessed formal authority to create new colonies, create or merge existing ones, or relocate boundaries.53See Eliga H. Gould, Zones of Law, Zones of Violence: The Legal Geography of the British Atlantic, Circa 1772, 60 Wm. & Mary Q. 471, 475 (2003). It was much less clear how postrevolutionary institutions and substantive law would identify borders or resolve disputes among states. Territorial decisions were vital to determining states’ tax policies and migration patterns, their political relationship to other states, and even their survival as social and economic units. During this period, questions about the location of “Virginia” and “New York” were also connected to territorial construction of the United States under the Articles and the Constitution. Even as splotches or lines on a map, the definition of statehood and the formulation of interstate nationhood were inextricably linked.

No single element of this eighteenth-century evidence stands alone in defining American states, and this Article’s explicit goal is to consider different ways of identifying statehood’s legal origins. In the aggregate, however, such evidence suggests that efforts to sequentially order the histories of states and the United States are flawed. There was no primordial moment when states came together, nor was there a moment when the United States conceived states out of nothing. As a matter of legal rhetoric and action, different categories of revolutionary government claimed and recognized each other’s authority in exactly the same time period. The states and United States leaned against one another as co-constitutive entities, and all of this might seem perfectly obvious, if it were not so widely forgotten and ignored.

A. Constitutions for Colonies, and for States

The earliest state constitutions were not called “state constitutions,” and establishing “states” is not what they tried to do. During these particular moments, it was unclear whether statehood, war, or independence would ever come to pass. Nevertheless, such prerevolutionary efforts to organize at the colonial level helped start the process of statehood, much as the Continental Congress started the process of interstate government.

The first of these provincial documents came from New Hampshire, during a period when prerevolutionary strife was affecting colonies in different ways.54Lawrence Friedman, The New Hampshire State Constitution, at xvii (2d ed. 2015). Massachusetts residents had thrown tea in Boston Harbor, leading Parliament to suspend the provincial assembly, increase the royal governor’s power, and impose harsh legal restrictions.55Gordon S. Wood, The American Revolution: A History 37–38 (2002). By contrast, New Hampshire’s Governor John Wentworth urged London to “restore the powers of [royal] Government,” while predicting that his own colony had fortunately “passed the crisis without much mischief.”56John Wentworth, Seizure of Arms and Powder at Fort William and Mary. The Finale of the Provincial Government in New-Hampshire., 23 New Eng. Hist. & Genealogical Reg. 274, 274–78 (1869) (letters of Governor Wentworth, Nov. 9, 1774). Wentworth spoke too soon. In late 1774, rioters sacked New Hampshire’s munitions depot, and the governor was powerless to chastise the thieves.57Id. at 277. Crowds pointed a stolen cannon at Wentworth’s front door, and the “frantic rage and fury of the people” made him retreat to the colonial armory that now lacked “men or ammunition.” 58Id. at 278. By the end of 1775, Wentworth left New Hampshire forever.59See Friedman, supra note 54, at 5.

Terrorizing the royal governor destabilized New Hampshire’s status as a British colony, and questions emerged about who should decide what happened next. New Hampshire residents mustered a “provincial congress” and militias to resist imperial troops.60Id. at 5, 7; Lynn Warren Turner, The Ninth State: New Hampshire’s Formative Years 10 (1983). Yet as a legal matter, colonists did not act alone in composing a new government. They urgently sought instructions from the Second Continental Congress:

We would have you immediately use your utmost endeavours to obtain the advice and direction of the Congress, with respect to a method for our administring Justice, and regulating our civil police. We press you not to delay this matter, as, its being done speedily . . . will probably prevent the greatest confusion among us.613 Journals of the Continental Congress 1774–1789, at 298 (Worthington Chauncey Ford ed., 1905) [hereinafter J.C.C. (1905)].

The Continental Congress itself was an improvised entity with uncertain authority. One historian called Philadelphia’s motley group of politicians “no doubt the strangest government we have ever had.”62Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence, at xxi (1997). Nevertheless, Congress answered New Hampshire’s request with formal legal recommendations. Local patriots should “call a full and free representation of the people” and, “if they think it necessary, establish such a form of government, as, in their judgment, will best produce the happiness of the people, and most effectually secure peace and good order in the province.”63J.C.C. (1905), supra note 61, at 319.

Did the Continental Congress have valid authority to promote anti-imperial policies?64The Continental Congress had already taken similar actions concerning Massachusetts—at the latter’s request—but Massachusetts did not produce a formal document establishing anti-imperial government. Hulsebosch, supra note 21, at 770–71. Most colonies simply followed the Continental Congress’s instructions directly, as though the latter were sufficient authorization in themselves. See id. at 778; 2 J.C.C. (1905), supra note 61, at 77, 83–84. Could New Hampshire have created a government without anyone’s approval?65For eighteenth-century arguments that New Hampshire’s constitution was invalid notwithstanding the Continental Congress’s support, see Bezaleel Woodward, Clerk, Address at Hanover (July 31, 1776), reprinted in 10 New Hampshire State Papers 229, 229–35 (Concord, N.H., Edward A. Jenks 1877), https://sos.nh.gov/archives-vital-records-records-management/archives/publications-collections/new-hampshire-state-papers/ (follow link to “Volume 10” to view full volume). The best answers to those questions of legal theory involve actions that the respective governments took in practice. Cooperation and coordination among colonial and intercolonial leaders made it unnecessary to resolve abstract and potentially delicate issues about who was sovereign over whom—or what sovereign superiority even meant in this context. New Hampshire’s effort to recompose its government deliberately exhibited profound interdependence. According to Congress, New Hampshire’s government was supposed to continue only “during . . . the present dispute between G[reat] Britain and the colonies.”66J.C.C. (1905), supra note 61, at 319. No one knew how long that dispute would last.

On January 5, 1776, New Hampshire’s arguably treasonous provincial politicians implemented Congress’s arguably treasonous recommendations, creating a new government that was operationally detached from homeland British law but intimately connected to intercolonial authority.67Friedman, supra note 54, at 5–6. New Hampshire explained that the “Sudden & Abrupt Departure of his Excellency John Wentworth . . . and Several of the Council” left the colony “Destitute of Legislation, and no Executive Courts being open to Punish Criminal Offenders; whereby the Lives and Propertys of the Honest People of this Colony, are Liable to the Machinations & Evil Designs of wicked men.”68N.H. Const. of 1776.

Such complaints about Wentworth’s departure were crocodile tears, and New Hampshire residents were not pining for new royal courts “to Punish Criminal Offenders.”69Id. New Hampshire residents were not trying to restore British officialdom. They were announcing new legal authority to “Pursue Such Measures as we Should Judge best for the Public Good.”70Id. Most important, New Hampshirites did not act entirely on their own initiative, which is why they did not invoke foundational or organic localism as a source of legal authority. On the contrary, New Hampshire’s radical charter expressed colonists’ wish “to establish Some Form of Government, Provided that Measures should be recommended by the Continental Congress.”71Id. (emphasis added).

Modern observers might not expect colonial dissidents in a revolutionary context to worry so much about legal technicalities. But it was only after “a Recommendation to that Purpose [was] Transmitted to us From the Said Congress” that the New Hampshire assembly sought to “Take up CIVIL GOVERNMENT for this Colony . . . . During the Present Unhappy and Unnatural Contest with Great Britain.”72Id. Through their explicit language and legal actions, New Hampshire politicians relied on the Continental Congress for authorization because they did not wish to act alone. The result was to produce a hybrid and mutually reliant legal entity from top to bottom.

New Hampshire’s leaders did not call their document a “constitution,” much less did anyone seek to identify a “state.”73See id. (using the word “state” exclusively to describe Great Britain as New Hampshire’s “parent state”); Hulsebosch, supra note 21, at 777 (describing New Hampshire’s “act of civil government”). Nonetheless, the event marked a new beginning. The governmental plan created exclusively North American institutions to regulate a self-identified “Colony of New-Hampshire” outside homeland British authority.74N.H. Const. of 1776 (emphasis omitted). The document also included medium-term electoral rules and bureaucratic responsibilities, just in case “the Present unhappy Dispute with Great Britain Should Continue longer than this present year.”75Id.

New Hampshire did not declare sovereign autonomy, emphasizing that “we Never Sought to throw off our Dependence upon Great Britain.”76Id. And whatever this new kind of “New Hampshire” was supposed to be, it absolutely was not independent from intercolonial authority. On the contrary, “we Shall Rejoice if Such a reconciliation between us and our Parent State can be Effected as shall be Approved by the Continental Congress in whose Prudence and Wisdom we confide.”77Id. The new provincial legislature was an explicitly tentative and subordinate entity, whose governmental institutions were authorized to function only insofar as “the Continental Congress Give no Instruction or Direction to the Contrary.”78Id. Constitutive legal actions were taken at both levels of government, interdependently, and at the same time.

The second colony to act was South Carolina, and its history paralleled that of New Hampshire. After South Carolina’s governor was physically threatened in the fall of 1775, he fled in January 1776.79Robert A. Olwell, “Domestick Enemies”: Slavery and Political Independence in South Carolina, May 1775–March 1776, 55 J.S. Hist. 21, 45–46 (1989). As with New Hampshire, South Carolina’s politicians sought approval from the Continental Congress before they attempted any governmental reorganization.80Adams, supra note 5, at 57; Terry W. Lipscomb, The South Carolina Constitution of 1776, 77 S.C. Hist. Mag. 138 (1976). See also J.C.C. (1905), supra note 61, at 326–27; S.C. Const. of 1776. On November 4, 1775, Congress recommended that a “full and free representation of the people” should establish a new form of government.81J.C.C. (1905), supra note 61, at 320, 326. And on March 26, 1776, South Carolina became the first colony in British North America to produce a “constitution” under that name.82S.C. Const. of 1776. South Carolinians insisted that they wanted to accommodate “the unhappy differences between Great Britain and America,” despite being “treated as rebels” by homeland British officials.83Id. South Carolina’s document was not optimistic about transatlantic reconciliation, however, and collective resistance to British imperialism throughout the colonies made their provincial constitution seem every day more permanent.

As an exercise of interdependent governance, South Carolinians asserted their new constitution’s legitimacy by repeating exact language from Congress’s authorization, promising “a full and free representation of the people of this colony.”84Id. art. I. Provincial actors did not act as though they were locally independent sovereigns. They were constructing a legal system that was intentionally mixed together with intercolonial authority. South Carolina’s constitution said that “the resolutions of the Continental Congress, now of force in this colony, shall so continue until altered or revoked by them.”85Id. art. XXVIII (emphasis added). The opposite of announcing absolute local sovereignty and self-governance, South Carolina’s constitution disclaimed authority for provincial legislators to contradict intercolonial resolutions—thereby granting the Continental Congress power that intercolonial officials could not have claimed on their own. South Carolina’s constitution vested power in the Continental Congress at the same time that the province was claiming power for itself.

The South Carolina Constitution did assert slightly more self-sufficiency than New Hampshire, perhaps reflecting the southern document’s emergence later in time. New colonial officeholders promised to “support, maintain and defend the Constitution of South Carolina” until disputes with Great Britain could be amicably resolved.86Id. art. XXXIII. But South Carolina’s Constitution also provided that the new colonial legislature must choose “delegates of this Colony in the Continental Congress.”87Id. art. XV. As a matter of legal rhetoric and action, the establishment of provincial government was linked with authority to obtain representation and participation in the intercolonial Congress. Systems of local and intercolonial authority appeared together as comparably elemental parts of South Carolina’s “constitution.” This again was a legal expression of interrelationship, not autonomy.

Modern observers often call documents from New Hampshire and South Carolina “the first state constitutions,” but that shifts them anachronistically forward in time, while also neglecting the creation of statehood as a legal category.88E.g., William Clarence Webster, Comparative Study of the State Constitutions of the American Revolution, 9 Annals Am. Acad. Pol. & Soc. Sci. 64 (1897). In the spring of 1776, there certainly were not any legal “states” called New Hampshire or South Carolina. None of North America’s colonial governments claimed that status, nor were they asserting independence from Britain, and the latter was a necessary predicate for any legal form of anticolonial statehood.

Cultural, social, and political continuities throughout the revolutionary era cannot erase the constitutive difference between colonies and states as legal entities. Properly understood, early efforts of New Hampshire and South Carolina to challenge British authority reveal the creation of mutually reinforcing legal entities that tried to mimic other colonies while urgently pursuing intercolonial authorization and support. Such legal language and documents were always seeking to achieve the “constitution” of something bigger than a merely isolated, autonomous locality. The precarious circumstances and political ambitions of revolutionary war would require state and interstate governments all at once.

The next step in the history of statehood was May 10, 1776. Citing the British Empire’s declining functionality, the Continental Congress recommended that all assemblies and conventions in “the United Colonies” should “adopt such government as shall, in the opinion of the representatives of the people, best conduce to the happiness and safety of their constituents in particular, and America in general.”894 Journals of the Continental Congress 1774–1789, at 341–42 (Worthington Chauncey Ford ed., 1906) [hereinafter J.C.C. (1906)]. Much like earlier documents from New Hampshire and South Carolina, the colonial and state constitutions that executed those instructions were never purebred expressions of organic localism.90Listed in chronological order, state constitutions after the May 10 resolution were issued by Virginia (June 29, 1776), New Jersey (July 3, 1776), Delaware (September 21, 1776), Pennsylvania (September 28, 1776), Maryland (November 11, 1776), and North Carolina (December 18, 1776). 7 The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of the States, Territories, and Colonies Now or Heretofore Forming the United States of America 3812 (Francis Newton Thorpe ed., 1909); 3 id. at 2594; 1 id. at 562; 5 id. at 3081; 3 id. at 1686; 5 id. at 2787. Constitutions from Georgia and New York followed in 1777, and Massachusetts produced a constitution in 1780. 1 id. at v, vii, x. Connecticut and Rhode Island continued to govern under their colonial charters throughout various fractions of the nineteenth century. Id. at iv, xii. They were the direct result of intercolonial prompts from Congress.

The congressional recommendation of May 10 transcended any particular colony’s circumstances or requests. The intercolonial government relied on its own initiative and judgment in suggesting that each colony should overthrow officials and create new governmental forms.91Adams, supra note 5, at 51. To be sure, Congress did not prescribe a substantive template for colonies to follow, and provincial documents were drafted in particular locations by diverse “Representatives of the People.”92See id. at 63. Richard Lee asked John Adams whether perhaps the Continental Congress should draft uniform charters for state governments to adopt. As a modern scholar explained, “Lee’s premise that the states were building new governments primarily so that they could work together . . . was obvious at the time, but is now largely forgotten.” Hulsebosch, supra note 21, at 783. For present purposes, however, the point is to show that layers of government were interdependent, not to measure their relative importance against one another. The Continental Congress directed that reforms should be considered throughout “the United Colonies,” with an eye toward the benefit of “their constituents in particular” as well as the collective benefit of “America in general.”93J.C.C. (1906), supra note 89, at 342.

Functional togetherness was a pervasive characteristic of the legal institutions that gradually emerged. The legal existence of provincial governments was repeatedly braided together with the similarly new Congress, as they both represented efforts to reform or replace British imperial government. In that wartime context, so-called “state constitutions” could never be isolated acts of local self-recognition. From the start, colonial and intercolonial governments aimed to serve harmonious objectives and perform overlapping functions.

One reason that the Continental Congress endorsed new provincial governments was to boost political support for independence, intercolonial opposition, and revolution that were increasingly probable and imminent.94See Wood, supra note 32, at 132. On May 15, the Continental Congress wrote a preamble elaborating its motive for authorizing provincial governments. The King and Parliament had mistreated the “United Colonies,” ignored their petitions for redress, and mustered armies for war. Under such circumstances, “it appears absolutely irreconcileable . . . for the people of these colonies now to take the oaths and affirmations necessary for the support of any government under the crown of Great Britain.”95J.C.C. (1906), supra note 89, at 357–58. Therefore, Congress claimed “it is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said crown should be totally suppressed, and all the powers of government exerted, under the authority of the people of the colonies.”96Id. Creating new provincial governments allowed colonies to resist “hostile invasions and cruel depredations of their enemies,” including British officials from the colonists’ ostensible legal homeland.97Id.

The intercolonial resolution and preamble did not use precise legal terminology about independence, states, or nationhood. Nevertheless, they characterized imperial mistreatment of any single colony—especially Massachusetts—as a terrible sin against all of them.98Id. at 342, 357–58; see Don Higginbotham, War and State Formation in Revolutionary America, in Empire and Nation: The American Revolution in the Atlantic World 54, 58–59 (Eliga H. Gould & Peter S. Onuf eds., 2005). This legal justification for new provincial governments tactically aggregated and amalgamated colonial wrongs, so that each individual colony—whatever its practical circumstances—could be equally aggrieved as a matter of law. Congress linked the ostensibly individuated response of creating local constitutions together with coordinated and collective preparation for intercolonial resistance, which eventually included war.99See Jack N. Rakove, The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress 17, 61–62 (1979); Higginbotham, supra note 98, at 61–62. In May 1776, protorevolutionary colonists at all levels of government hoped that new provincial institutions and new intercolonial institutions might emerge and continue as legally interdependent and co-constitutive entities. Separate statehood would obviously have been a recipe for political failure and military defeat.

Congress’s use of the words “colonies” and “United Colonies” did not refer to legal entities that were controlled by Britain, and neither the resolution nor the preamble sought to invoke British imperial authority. On the contrary, the Continental Congress used its own questionably legitimate powers to manufacture provincial governments of equally questionable legitimacy, in order that “every kind of authority under the [British] crown should be totally suppressed.”100J.C.C. (1906), supra note 89, at 357–58; see Rakove, supra note 98, at 65–66. The resolution and preamble implied that disgruntled colonists could choose to unseat governors, displace judges, and disobey their King with an authorizing citation to the Continental Congress. But of course, no one except protorevolutionary Americans would accept Congress’s authority in the first place. Despite such inevitable risks of circularity, the lean-to architecture of American law was effective. In 1776, multiple layers of interdependent government seemed indispensable, and every North American colony that created a new governmental charter did so with some kind of encouragement from Congress.101Adams, supra note 5, at 60–93.

Revolutionary Virginia—the largest and strongest insurgent colony—offers one more example of interdependent provincial charters. On the same day that Congress issued its preamble in May 1776, a convention of Virginian dissidents unanimously resolved that their delegates in the Continental Congress should “propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependance upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain.”102Preamble and Resolution of the Virginia Convention, May 15, 1776, Instructing the Virginia Delegates in the Continental Congress to “Propose to That Respectable Body to Declare the United Colonies Free and Independent States” (1776), reprinted in Documents Illustrative of the Formation of the Union of the American States, H.R. Doc. No. 69-398, at 19, 20 (Charles C. Tansill ed., 1927) [hereinafter Virginia Resolution] (emphasis omitted); John Dinan, The Virginia State Constitution 4 (2d ed. 2014). Virginian colonists understood that their provincial government should be secondary in both of those legal projects. Virginians authorized intercolonial representatives to make whatever “declaration” and take “whatever measures may be thought proper and necessary by the Congress for forming foreign alliances, and a Confederation of the Colonies, at such time and in the manner as to them shall seem best.”103Virginia Resolution, supra note 102 (emphasis added).

Virginia’s own state convention prescribed that the Continental Congress was the best institution for declaring independence, organizing a confederation, and transforming “Colonies” into “States.”104Id. Even powerful Virginia did not claim statehood alone, much less did Virginians explain what statehood or interstatehood should mean. All of those were matters for Congress to debate and resolve as a collective matter, uniformly, and across the board. The legal category of statehood itself did not belong to—and was not defined by—any state on its own.

The Virginia Resolution contained one provincially oriented caveat, which echoed earlier provisions from New Hampshire and South Carolina: “That the power of forming Government for, and the regulations of the internal concerns of each Colony, be left to the respective Colonial Legislatures.”105Id. Subsequent territorial disputes make it especially hard to say where Virginia’s “internal concerns” were located as a geographic matter, much less as an analytical one.106See infra Section II.C (describing eighteenth-century territorial disputes); Section III.C (suggesting that political institutions should define what qualifies as “internal”). For present purposes, the crucial detail is that Virginians and congressional politicians reached the same legal conclusion on the very same day: both levels of government agreed that protorevolutionary colonists must use intercolonial mechanisms to announce independence and their own statehood as well.