Stubborn Things: An Empirical Approach to Facts, Opinions, and the First Amendment

Daniel E. Herz-Roiphe*

Over the past fifteen years, a brutal civil war has claimed more than five million lives in the Democratic Republic of Congo (“DRC”), making it the deadliest recorded conflict since World War II.[1] The belligerents fund their operations through a lucrative trade in metals, some of which ultimately make their way into American consumer goods.[2] In 2010, Congress took action, directing the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) to require firms using minerals from the DRC to investigate and disclose the provenance of their merchandise.[3] The SEC responded by promulgating regulations that compel manufacturers to file “conflict minerals reports” describing their product-sourcing efforts and listing any items that have “not been found to be ‘DRC conflict free.’ ”[4]

Shortly after this Conflict Minerals Rule hit the Federal Register, the National Association of Manufacturers (“NAM”)—an industry trade association—filed suit, claiming, among other things, that the regulation violated the First Amendment by forcing companies to speak when they would rather remain silent.[5] Since it is well established that the First Amendment protects “the decision of both what to say and what not to say,”[6] NAM’s argument sketched the outlines of a colorable constitutional claim.

Yet “[p]urely commercial speech,” such as a corporation’s speech about its products, “is more susceptible to compelled disclosure requirements” than other types of communication.[7] In the seminal case of Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Council, the Supreme Court held that requiring commercial speakers to disclose “purely factual and uncontroversial information” triggers only rational basis scrutiny.[8] The SEC accordingly argued that its Conflict Minerals Rule raised minimal First Amendment concerns, since it only required companies to disclose a fact—whether their products could, or could not, be verified to have no connection to armed groups in the DRC.[9]

The D.C. Circuit disagreed. It found that Zauderer was inapplicable and that the Conflict Minerals Rule failed to meet the more exacting demands of the Central Hudson test,[10] which applies to commercial speech outside Zauderer’s purview and requires that any restriction be no “more extensive than is necessary” to serve the government’s interest in regulating.[11]

The court advanced two rationales in explaining why the Conflict Minerals Rule failed to qualify for rational basis review. The first—that “Zauderer is ‘limited to cases’” regarding “ ‘the State’s interest in preventing deception of consumers’ ”[12]—has since been repudiated in an en banc D.C. Circuit decision in a different case.[13] But the second—that the conflict mineral disclosure was not truly “factual and non-ideological” since it required a manufacturer to “tell consumers that its products are ethically tainted”[14]—lies at the heart of a persistent doctrinal puzzle: What are the limits of a “factual” disclosure for the purposes of the First Amendment?[15]

This question will soon take center stage as the D.C. Circuit rehears NAM in order to determine “the meaning of ‘purely factual and uncontroversial information.’ ”[16] Debates over what counts as a “fact” have also animated other controversial cases—most notably R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA,[17] in which the D.C. Circuit rejected the FDA’s graphic cigarette warnings—and these debates carry broader implications for the First Amendment’s migration into the domain of public health,[18] where courts have been asked whether pregnancy centers can be forced to disclose that they do not offer abortions[19] and whether doctors can be required to show sonogram images to pregnant mothers.[20]

This Essay offers an empirical approach to the problem, rooted in an argument that the underlying rationale for the fact/opinion distinction in compelled speech doctrine tells us something about how this distinction should be policed. Commercial speech enjoys protection by virtue of its value to listeners; it is from the listener’s vantage point, then, that courts should assess whether a compelled disclosure is fact or opinion. And if we are interested in learning how disclosures will affect listeners, we might try asking them, just as courts adjudicating trademark suits frequently use consumer surveys to determine how customers understand the meaning of logos and slogans.

To this end, the Essay reports the results of an original survey that presented respondents with the disclosures at issue in a number of recent compelled speech cases. The survey asked the respondents to categorize these disclosures as conveying facts or opinions, and the respondents ultimately proved adept at distinguishing between the two—an outcome that suggests that consumer surveys could be a valuable resource for courts as they grapple with disclosures in the First Amendment context. The survey also indicated that the respondents had dramatically different understandings than the D.C. Circuit of the controversial disclosures at issue in NAM and R.J. Reynolds. This finding offers a new and important perspective on how courts should treat these, and similar, forms of mandated speech in the ongoing legal battles over their constitutional validity.

I. Why Does the Fact/Opinion Distinction Matter, and How Should We Enforce It?

Appreciating why courts apply the fact/opinion distinction in compelled commercial speech cases can help us understand how they should apply it. In noncommercial contexts, First Amendment doctrine grounds free-speech protection in the autonomous speaker’s right to say—or not say—what she wishes.[21] As a result, compelled-speech protections “appl[y] not only to expressions of value, opinion, or endorsement” but also to “statements of fact.”[22]

In the commercial context, by contrast, the doctrinal justification for free speech focuses on the listener rather than the speaker. Commercial speech “is constitutionally protected not so much because it pertains to the seller’s business as because it furthers the societal interest in the ‘free flow of commercial information.’ ”[23] This focus on the listener accounts for courts’ especially permissive attitude toward compelled factual disclosures. “Because the extension of First Amendment protection to commercial speech is justified principally by the value to consumers of the information such speech provides,” a speaker’s “constitutionally protected interest in not providing any particular factual information . . . is minimal.”[24]

Government attempts to compel commercial speakers to spout opinions, however, remain suspect because such attempts can have pernicious effects not only on speakers but also on listeners and the formation of public opinion as a whole.[25] “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.”[26] When the state forces others to advocate for its beliefs, it does not simply provide information that allows consumers to make intelligent decisions; it forces commercial speakers to tell consumers what to think, an affront to the principle that “[a]uthority . . . is to be controlled by public opinion, not public opinion by authority.”[27] As a result, even in commercial contexts, “First Amendment values are at serious risk if the government can compel a particular citizen, or a discrete group of citizens, to pay special subsidies for speech on the side that it favors.”[28]

Courts thus treat factual and opinion disclosures differently because they do different things to their audiences—while the former educate public opinion, the latter control it. This rationale for distinguishing between facts and opinions suggests a corresponding method for doing so: if we want to determine in which category a particular disclosure falls, we should assess its effect on the audience. Such a determination should depend on what an average consumer would actually experience when encountering the disclosure.[29]

The law of defamation offers a clear analogue. In a defamation suit, the meaning of allegedly defamatory words is determined “from the commonsense perspective from which they would be interpreted by the average member of the public.”[30] This includes the determination of whether a statement conveys facts or opinions. Because the First Amendment “provides protection for statements that cannot ‘reasonably [be] interpreted as stating actual facts’ about an individual,”[31] juries in defamation suits must often specifically assess “whether the average [listener] would conclude from the language of the statement and its context that [the defendant] was making a statement of fact.”[32]

How could courts undertake the similar task of determining reasonable consumers’ understanding of compelled disclosures? One disarmingly straightforward possibility would be to ask these consumers what they think. This is not a fanciful suggestion; soliciting consumer sentiments is actually a widespread practice in trademark litigation. The Lanham Act prohibits any unauthorized use of a trademark that “is likely to cause confusion.”[33] One of the most common ways for litigants to establish—or dispute—the existence of confusion is to employ surveys that gauge consumers’ reactions to an allegedly infringing mark.[34] Although these surveys are “often subject to criticism and varying interpretations,” they are nonetheless “a routine and well-established feature of trademark practice.”[35]

Similar practices could inform courts’ understanding of the meaning of compelled disclosures.[36] Admittedly, there are some limitations: Surveys cannot resolve whether statements contain opinions or facts in the way they can demonstrate the presence or absence of consumer confusion in trademark cases. If consumers report being confused, then for all intents and purposes they are confused; by contrast, if consumers report that a statement is factual, that does not necessarily make it so. Yet surveys may still provide one of the best available windows into how compelled disclosures actually affect the audiences that hear and read them. If a consumer perceives a statement as opinionated, that perception reveals something important about how the statement operates in the real world. Furthermore, the Lanham Act experience suggests that integrating surveys into litigation is feasible and effective. In fact, survey evidence has already featured in important compelled-speech decisions: the D.C. Circuit’s AMI opinion specifically cited survey evidence—which “indicat[ed] that 71–73 percent of consumers would be willing to pay for country-of-origin information about their food”—in support of the government’s interest in imposing labeling requirements for meat packages.[37] Utilizing similar evidence to litigate the distinction between fact and opinion disclosures would require no great stretch of the imagination. The next Part accordingly presents the results of original survey research designed to test how consumers evaluate compelled disclosures.

II. A Survey-Based Test of Facts and Opinions

In order to investigate how ordinary observers understand the nature of particular compelled disclosures, I conducted a survey of 207 individuals recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk online marketplace.[38] The survey presented respondents with the disclosures at issue in several recent commercial speech cases, asking them to decide whether these disclosures contained facts or opinions. In categorizing the disclosures, the respondents displayed high levels of agreement, and in most cases their understandings echoed those of courts. In a couple of instances, however, their conclusions diverged, implying that judges’ determinations may not always reflect the perspective of ordinary listeners.

A. Methodology

The survey contained three parts: (1) an introductory primer on the distinction between facts and opinions; (2) a substantive section in which participants were presented, in random order, with seven disclosures drawn from notable cases and were then asked to determine whether the content of each disclosure was “purely factual” or contained “at least some opinions”; and (3) a final section collecting demographic information.

The survey began by explaining the difference between facts and opinions. Because the exact contours of this distinction are the subject of considerable philosophical debate,[39] for practical reasons the survey relied on a simple criterion frequently employed by courts: that facts, unlike opinions, can be verified objectively.[40] The survey explained this idea to participants by using a slightly more elaborate version of California’s jury instruction for defamation[41]:

This survey asks you to distinguish between statements of fact and statements of opinion. A factual statement can be proven true or false objectively—in other words, you could know whether it was true or not just by looking carefully at the world. Opinions express judgments that cannot be proven true or false objectively—judgments about the right answer to a moral or political question, for example.

The survey then required participants to classify correctly two unambiguous practice statements—“California is the most populous state in the country” and “California is the best state in the country to live in”—as facts or opinions before moving on.

The next section presented participants with seven randomly ordered disclosures made by the fictional firm “Acme, Inc.” Participants were asked to characterize each disclosure as containing “purely factual information” or “at least some opinions.” Six of the seven disclosures were either the exact disclosures, or paraphrases of the exact disclosures, at issue in notable First Amendment cases[42]:

- Conflict Minerals: Acme, Inc. disclosed that its products “had not been found to be ‘DRC-conflict free,’ ” as in NAM.[43]

- Country-of-Origin Labeling: Acme, Inc. disclosed the country in which the animals used to produce its meat products were born, as in AMI.[44]

- Mushroom Advertising: Acme, Inc. stated that all mushrooms were equally good no matter whether they were produced by Acme or not, similar to the advertising that respondent was compelled to support in United States v. United Foods.[45]

- Employee Rights: Acme, Inc. informed workers of their right to unionize under the National Labor Relations Act, using language from the required disclosure at issue in National Association of Manufacturers v. NLRB.[46]

- Sex-Offender Registration: Acme, Inc. disclosed that its Chief Operational Officer was a registered sex offender, echoing the circumstances of the First Amendment challenge to sex-offender registration presented in United States v. Arnold.[47]

- Graphic Cigarette Warnings: Acme, Inc. placed an image of a man with a hole in his throat on its cigarette packaging (respondents were shown the actual image). The image was accompanied by text that proclaimed “cigarettes are addictive” and gave the number for a quitting hotline, as required by the FDA in R.J. Reynolds.[48]

One additional disclosure was wholly fabricated in order to provide a baseline gauging respondents’ reactions to the kind of pure political compulsion that has rarely been litigated in American courts:

- Political Compulsion: Acme, Inc. affirmed its support for the President and encouraged consumers to buy its products in order to display their support for the President as well.

After the participants had characterized each of these statements as “purely factual” or containing “at least some opinions,” the survey solicited demographic information on gender, age, race, education, income, political ideology, and smoking status.

B. Results

1. Demographics

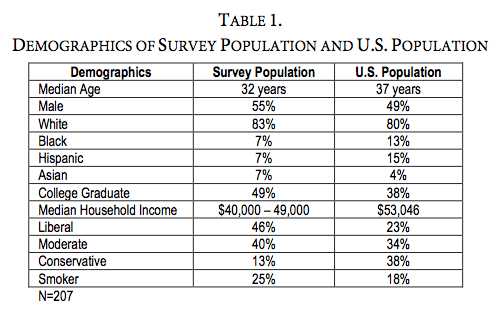

The demographics of the study pool indicated that it was fairly representative of the U.S. population, although slightly younger, more male, more liberal, poorer, and better educated.[49]

While not perfectly representative, the survey population constituted a better approximation of the American population than many samples of convenience. Furthermore, none of the deviations from national averages appears to have affected the results, as there were no meaningful associations between subjects’ demographic traits—including political affiliation—and their reactions to the disclosures.[50]

2. Disclosures

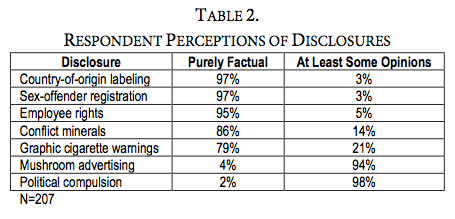

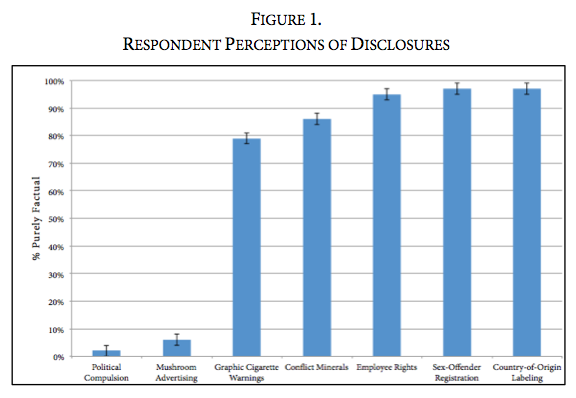

Participants’ characterizations of the disclosures were, in most cases, highly consistent. Three disclosures—country-of-origin labeling, employee rights, and sex-offender registration—were almost unanimously regarded as “purely factual.” Two disclosures—mushroom advertising and political compulsion—were almost unanimously regarded as containing “at least some opinions.” The two remaining disclosures—conflict minerals and graphic cigarette warnings—both of which have inspired controversial D.C. Circuit opinions, incited the most disagreement. But a sizeable majority (86% for conflict minerals and 79% for graphic cigarette warnings) still identified each as a “purely factual” disclosure.

There were no notable interactions between demographic variables and respondents’ characterization of the disclosures, including between smoking status and the perception of the cigarette warning disclosure.

C. Discussion

Participants appeared to distinguish between fact and opinion in reasonable ways. In “clear” cases—that is, where courts have found compelled speech to be obviously factual, as in AMI,[51] or obviously opinionated, as in United Foods,[52] without prompting objection from commentators or even the litigating parties themselves—the survey respondents overwhelmingly agreed. The respondents were able to recognize even—as the Fifth Circuit did[53]—that sex-offender status is a factual matter in spite of the obvious negative connotations it carries. They were also able to classify disclosures involving politically charged issues, such as labor unions and the president, in ways that accord with doctrine and intuition.[54] Finally, participants’ responses varied little based on their personal characteristics or political ideology, which suggests that they engaged cognitively with the fact/opinion determination rather than simply “voting their politics,” a tendency observed in other contexts.[55]

The two “close” cases, stemming from court decisions that have invited challenges and criticism, generated slightly higher levels of disagreement among the participants. The difficulty of characterizing these disclosures as factual or opinionated has attracted the attention of courts and commentators;[56] it is therefore unsurprising that the participants mildly diverged in their responses as well. It is also notable that the majority of respondent opinions cut sharply against the rulings of the D.C. Circuit in NAM and R.J. Reynolds. Where the NAM court saw a company confessing “blood on its hands,”[57] 86% of respondents saw a “purely factual” disclosure; and where the R.J. Reynolds panel saw “unabashed attempts to evoke emotion (and perhaps embarrassment) and browbeat consumers into quitting,”[58] 79% of respondents saw only facts.

Of course, this discrepancy does not somehow “prove” that the courts were wrong to characterize the conflict-mineral and cigarette disclosures as they did. But it does add another voice to the conversation—a voice that speaks with a certain authority given its direct connection to the ordinary listeners of whom commercial speech doctrine is so solicitous in the first place.

As Dan Kahan and others have shown, judges can sometimes have an unjustified certainty that their understanding of a particular set of facts is the only reasonable interpretation.[59] Such narrow-mindedness proves especially dangerous for tasks like policing the fact/opinion distinction in compelled commercial speech, where the key question is how disclosures will affect ordinary consumers, not judges. Accordingly, incorporating evidence of ordinary consumer understandings—like the survey conducted here, or even the evidence on meat-labeling preferences that the D.C. Circuit cited in AMI—into commercial speech litigation could assist judges in navigating the thorny fact/opinion issues that will only continue to arise.

Conclusion

Recent battles over compelled commercial speech confirm that facts are indeed stubborn things—not only do they resist being ignored or manipulated but sometimes they even refuse to be neatly categorized as facts. In such circumstances, courts should consider why we distinguish facts from opinions under the First Amendment at all. An overview of commercial speech doctrine reveals that we do so because of the differential effects that factual and opinion disclosures have on their audiences. This concern with the listener suggests that courts can obtain valuable guidance by considering evidence of how ordinary consumers actually understand compelled disclosures.

This Essay has made a preliminary attempt to provide such evidence. The results offer strong support for using consumer surveys to categorize disclosures for First Amendment purposes. They also present a new perspective on the hotly contested disclosures that D.C. Circuit panels struck down in NAM and R.J. Reynolds. While the judges in these cases may have viewed the mandated statements as opinion laden, a large majority of survey respondents characterized them as purely factual. Given the audience-focused structure of commercial speech doctrine, the respondents’ dissenting voice cannot be dismissed lightly. When the D.C. Circuit rehears NAM—and when other courts confront similar problems—they should consider taking into account empirical findings like those presented here.

Appendix:

Survey Text

I. Practice Questions

This survey asks you to distinguish between statements of fact and statements of opinion. A factual statement can be proven true or false objectively—in other words, you could know whether it was true or not just by looking carefully at the world. Opinions express judgments that cannot be proven true or false objectively—judgments about the right answer to a moral or political question, for example.

For practice, try categorizing these two statements:

1. “California is the most populous state in the country.”

- Factual information

- Opinions

2. “California is the best state in the country to live in.”

- Factual information

- Opinions

II. Disclosures

Instructions:

Companies are frequently required to make disclosures about their products, services, or business practices. The following exercises ask you to read and evaluate company disclosures.

1. Please carefully read the following disclosure that Acme, Inc., a maker of cell phones, posted on its website:

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is a country in Africa that has experienced a long civil war. Federal law defines a product to be “DRC conflict free” if that product does not contain “minerals that directly or indirectly finance or benefit armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or an adjoining country.” Acme cell phones have not been found to be “DRC conflict free.”

Does this disclosure provide only factual information—statements that can be objectively proven true or false just by looking at the world? Or does it also express opinions—judgments about the world and how people should feel or act that cannot be objectively proven true or false?

- Purely factual information

- At least some opinions

2. Please carefully read the following disclosure that Acme, Inc., a maker of meat products, posted on its product labeling:

The animals used to produce this meat were born and raised in Canada and harvested in the United States.

Does this disclosure provide only factual information—statements that can be objectively proven true or false just by looking at the world? Or does it also express opinions—judgments about the world and how people should feel or act that cannot be objectively proven true or false?

- Purely factual information

- At least some opinions

3. Please carefully read the following disclosure that Acme, Inc., a maker of mushrooms, posted in its product advertising:

Mushrooms are worth consuming whether they are branded as Acme mushrooms or not; all mushrooms are equally good.

Does this disclosure provide only factual information—statements that can be objectively proven true or false just by looking at the world? Or does it also express opinions—judgments about the world and how people should feel or act that cannot be objectively proven true or false?

- Purely factual information

- At least some opinions

4. Please carefully read the following disclosure that Acme, Inc. posted on its website:

EMPLOYEE RIGHTS UNDER THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS ACT

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) guarantees the right of employees to organize and bargain collectively with their employers. Under the NLRA, you have the right to:

- Organize a union to negotiate with your employer concerning your wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment.

- Form, join or assist a union.

- Bargain collectively through representatives of employees’ own choosing for a contract with your employer setting your wages, benefits, hours, and other working conditions.

Does this disclosure provide only factual information—statements that can be objectively proven true or false just by looking at the world? Or does it also express opinions—judgments about the world and how people should feel or act that cannot be objectively proven true or false?

- Purely factual information

- At least some opinions

5. Please carefully read the following disclosure that Acme, Inc., a maker of shoes, posted on its website:

Acme supports the President and his party. You should buy Acme shoes in order to show your support for the President as well.

Does this disclosure provide only factual information—statements that can be objectively proven true or false just by looking at the world? Or does it also express opinions—judgments about the world and how people should feel or act that cannot be objectively proven true or false?

- Purely factual information

- At least some opinions

6. Please carefully read the following disclosure that Acme, Inc. posted on its website:

The Chief Operational Officer (COO) of Acme, Inc. was once convicted of a sex crime and is registered with the state as a sex offender.

Does this disclosure provide only factual information—statements that can be objectively proven true or false just by looking at the world? Or does it also express opinions—judgments about the world and how people should feel or act that cannot be objectively proven true or false?

- Purely factual information

- At least some opinions

7. Please carefully read the following disclosure that Acme, Inc., a maker of cigarettes, posted on its product labeling:

Proposed Acme Cigarette Box Label Disclosure:

Does this disclosure provide only factual information—statements that can be objectively proven true or false just by looking at the world? Or does it also express opinions—judgments about the world and how people should feel or act that cannot be objectively proven true or false?

- Purely factual information

- At least some opinions

III. Demographics

1. What is your gender?

- Male

- Female

2. How old are you?

3. What is your race? Check all that apply.

- White/Caucasian

- Black, African-American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian or Asian-American

- Hispanic

- Pacific Islander

- Some other race

4. Please indicate the highest level of education completed.

- Grammar school

- High School or equivalent

- Vocational/technical school (2 year)

- Some College

- College Graduate (4 year)

- Master’s Degree (MS)

- Doctoral Degree (PhD)

- Professional Degree (MD, JD, etc.)

- Other

5. Please indicate your current household income in U.S. dollars.

- Under $10,000

- $10,000 – $19,999

- $20,000 – $29,999

- $30,000 – $39,999

- $40,000 – $49,999

- $50,000 – $74,999

- $75,000 – $99,999

- $100,000 – $150,000

- Over $150,000

- Rather not say

6. My political views are . . .

- Extremely liberal

- Liberal

- Slightly left-of-center

- Moderate

- Slightly right-of-center

- Conservative

- Extremely conservative

7. Are you a smoker?

- Yes

- No

8. Earlier in this survey you were shown an image of a cigarette carton. What was the image on the front of the carton?

- A picture of blackened lungs

- A man with a hole in his throat

- A man on a respirator

- A child coughing

- Can’t remember

- Image didn’t load properly

* J.D. Candidate, May 2015, Yale Law School. Many thanks to Robert Post and Amy Kapczynski for inspiring this project, to Roseanna Sommers for making it possible, to Phoebe Clarke, Connor Clarke, Lev Menand, and my father for their helpful comments, and to Matt McCurdy and the editors of the Michigan Law Review.

[1]. Special Report: Congo, Int’l Rescue Committee, http://www.rescue.org/special-reports/special-report-congo-y [http://perma.cc/CCK9-B383] (last visited Dec. 17, 2014).

[2]. See Conflict Minerals, 77 Fed. Reg. 56,274, 56,284–85 (Sept. 12, 2012).

[3]. See 15 U.S.C. § 78m(p)(1)(A) (2012).

[4]. 77 Fed. Reg. at 56,320.

[5]. See Nat’l Ass’n of Mfrs. v. SEC (NAM), 748 F.3d 359, 365 (D.C. Cir. 2014).

[6]. Riley v. Nat’l Fed’n of the Blind, 487 U.S. 781, 796–97 (1988).

[7]. Id. at 796 n.9.

[8]. 471 U.S. 626, 651 (1985).

[9]. NAM, 748 F.3d at 370.

[10]. Id. at 372.

[11]. Cent. Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Pub. Serv. Comm’n of N.Y., 447 U.S. 557, 566 (1980).

[12]. NAM, 748 F.3d at 371 (quoting R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205, 1213 (D.C. Cir. 2012)).

[13]. Am. Meat Inst. v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric. (AMI), 760 F.3d 18, 20 (D.C. Cir. 2013) (en banc) (“We now hold that Zauderer in fact does reach beyond problems of deception . . . .”).

[14]. NAM, 748 F.3d at 371.

[15]. See, e.g., Carolina Mala Corbin, Compelled Disclosures, 65 Ala. L. Rev. 1277, 1286–90 (2014); Ellen P. Goodman, Visual Gut Punch: Persuasion, Emotion, and the Constitutional Meaning of Graphic Disclosure, 99 Cornell L. Rev. 513, 545 (2014); Jennifer M. Keighley, Can You Handle the Truth? Compelled Commercial Speech and the First Amendment, 15 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 539, 605–13 (2012); Andrew C. Budzinski, Note, A Disclosure-Focused Approach to Compelled Commercial Speech, 112 Mich. L. Rev. 1305, 1330–33 (2014).

[16]. Order for Rehearing at 1, NAM, 748 F.3d 359 (No. 13-5252). The court also granted rehearing on the questions of “[w]hat effect, if any,” the en banc AMI holding had on “the First Amendment issue in this case regarding the conflict mineral disclosure requirement,” and whether “determination of what is ‘uncontroversial information’ ” is “a question of fact.” Id. The D.C. Circuit has deferred the parties’ petition for en banc review pending the disposition of the panel rehearing. Order Granting Motion for Leave to File at 1, NAM, 748 F.3d 359 (No. 13-5252).

[17]. 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012); see also Nat’l Ass’n of Mfrs. v. NLRB, 717 F.3d 947 (D.C. Cir. 2013) (addressing the constitutionality of a regulation requiring employers to notify employees of their rights under the National Labor Relations Act); Spirit Airlines, Inc. v. U.S. Dep’t of Transp., 687 F.3d 403 (D.C. Cir. 2012) (challenging the constitutionality of airline ticket price disclosure rules); Disc. Tobacco City & Lottery, Inc. v. United States, 674 F.3d 509 (6th Cir. 2012) (considering graphic cigarette warnings).

[18]. See generally Seth E. Mermin & Samantha K. Graff, The First Amendment and Public Health, at Odds, 39 Am. J.L. & Med. 298 (2013) (critiquing the First Amendment’s expansion into public health).

[19]. See Evergreen Ass’n v. City of New York, 740 F.3d 233 (2d Cir. 2014).

[20]. See Tex. Med. Providers Performing Abortion Servs. v. Lakey, 667 F.3d 570 (5th Cir. 2012).

[21]. Wooley v. Maynard, 430 U.S. 705, 714 (1977) (“The right to speak and the right to refrain from speaking are complementary components of the broader concept of ‘individual freedom of mind.’ ” (quoting Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 637 (1943))).

[22]. Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian & Bisexual Grp. of Bos., 515 U.S. 557, 573 (1995).

[23]. First Nat’l Bank of Bos. v. Bellotti, 435 U.S. 765, 783 (1978) (quoting Va. State Bd. of Pharmacy v. Va. Consumer Council, Inc., 425 U.S. 748, 764 (1976)). Before 1976, commercial speech enjoyed no constitutional protection at all. See Valentine v. Chrestensen, 316 U.S. 52 (1942).

[24]. Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Council, 471 U.S. 626, 651 (1985) (citing Va. State Bd. of Pharmacy, 425 U.S. 748).

[25]. For a discussion of the relationship between the First Amendment and the process of public-opinion formation, see Robert C. Post, Citizens Divided: Campaign Finance Reform and the Constitution 3–44 (2014), and Robert C. Post, Democracy, Expertise, and Academic Freedom: A First Amendment Jurisprudence for the Modern State 2–60 (2012).

[26]. Barnette, 319 U.S. at 642.

[27]. Id. at 641.

[28]. United States v. United Foods, 533 U.S. 405, 411 (2001).

[29]. See Robert Post, Compelled Commercial Speech 43–44 (Yale Law Sch. Pub. Law Research Paper No. 519, 2014).

[30]. Rodney A. Smolla, 1 Law of Defamation § 4:20 (2d ed. 2014).

[31]. Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co., 497 U.S. 1, 20 (1990) (alteration in original) (quoting Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46, 50 (1988)).

[32]. Judicial Council of Cal. Civil Jury Instruction 1707 (2014). Another similar example comes from true-threat jurisprudence, in which courts often look to a reasonable listener’s reaction to assess whether a statement is threatening. See, e.g., United States v. White, 670 F.3d 498, 509 (4th Cir. 2012) (putting forth an “objective test . . . of how a reasonable recipient would understand the statement”). This term, the Supreme Court will consider whether a reasonable listener’s understanding of a statement as threatening suffices to create a “true threat” under the First Amendment, or whether the speaker must also have intended the statement as a threat. See Elonis v. United States, 134 S. Ct. 2819 (2014).

[33]. 15 U.S.C. § 1114(1)(a) (2012).

[34]. See Irina D. Manta, In Search of Validity: A New Model for the Content and Procedural Treatment of Trademark Infringement Surveys, 24 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L.J. 1027, 1031 (2007) (“The importance of consumer surveys in the context of trademark litigation cannot be overemphasized . . . . [S]urveys constitute the main tool to measure the mental state of some segment of the consuming public.”); see also Robert C. Bird & Joel H. Steckel, The Role of Consumer Surveys in Trademark Infringement: Empirical Evidence from the Federal Courts, 14 U. Pa. J. Bus. L. 1013 (2012) (providing an overview of survey practice in federal courts).

[35]. Clicks Billiards, Inc. v. Sixshooters, Inc., 251 F.3d 1252, 1262 (9th Cir. 2001).

[36]. Of course, one could go a step further and argue that juries, rather than courts, should make fact/opinion determinations. This Essay’s proposal represents something of a middle ground.

[37]. Am. Meat Inst. v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric. (AMI), 760 F.3d 18, 24 (D.C. Cir. 2013).

[38]. The survey was limited to American respondents. For a discussion of the viability of using Mechanical Turk for academic research, see, for example, David G. Rand, The Promise of Mechanical Turk: How Online Labor Markets Can Help Theorists Run Behavioral Experiments, 299 J. Theoretical Biology 172 (2012).

[39]. See, e.g., Charles Taylor, Philosophy and the Human Sciences 17–19 (1985).

[40]. See, e.g., Ollman v. Evans, 750 F.2d 970, 981 (D.C. Cir. 1984) (“In assessing whether . . . statements are facts, rather than opinion, courts should . . . consider the degree to which the statements are verifiable—is the statement objectively capable of proof or disproof?”).

[41]. Judicial Council of Cal. Civil Jury Instruction 1707 (2014).

[42]. For the full text of prompts and survey questions, see infra Appendix.

[43]. 748 F.3d 359 (D.C. Cir. 2014).

[44]. 760 F.3d 18 (D.C. Cir. 2013).

[45]. 533 U.S. 405 (2001).

[46]. 717 F.3d 947 (D.C. Cir. 2013).

[47]. 740 F.3d 1032 (5th Cir. 2014).

[48]. 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012).

[49]. For U.S. demographic information, see USA Quickfacts,U.S. Census Bureau, http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html [http://perma.cc/94WY-NQTC] (last modified July 8, 2014);United States, CIA World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html [https://perma.cc/9Q29-F838] (last visited Dec. 17, 2014); Liberal Self-Identification Edges Up,Gallup (Jan. 10, 2014), http://www.gallup.com/poll/166787/liberal-self-identification-edges-new-high-2013.aspx [http://perma.cc/EKU7-74U9]; and Smoking and Tobacco Use, Centers for Disease Control, http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/ [http://perma.cc/EU4E-MN66] (last visited Dec. 17, 2014).

[50]. Out of the dozens of possible cross-tabulations between demographic characteristics and responses to disclosures, there were a couple of statistically significant associations: white respondents appeared to be more likely to characterize the sex offender disclosure as purely factual (p = 0.02), and poorer respondents were more likely to characterize the mushroom disclosure as purely factual (p = 0.03). But since there is no obvious explanation for why these patterns would emerge, and since they did not carry over to other questions, it seems likely that they were solely the product of statistical noise.

[51]. Am. Meat Inst. v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric. (AMI), 760 F.3d 18, 27 (D.C. Cir. 2013) (“AMI does not contest that country-of-origin labeling qualifies as factual . . . .”).

[52]. United States v. United Foods, 533 U.S. 405, 411 (2001) (finding “no apparent principle which distinguishes out of hand minor debates about whether a branded mushroom is better than just any mushroom” from major political questions).

[53]. United States v. Arnold, 740 F.3d 1032, 1035 (5th Cir. 2014) (refusing to accept that registration forces a sex offender “to affirm a religious, political, or ideological belief he disagrees with”).

[54]. The point is not that survey participants were automatically “right” any time they confirmed a court’s holding. Rather, it is that participants’ alignment with courts in particularly clear-cut cases suggests that they understood and took seriously the task assigned to them. If participants gave mixed responses on whether meat labeling was factual, for example, the best interpretation would probably be that they failed to comprehend the question, not that the country in which meat originates is a matter of opinion. That participants provided coherent responses in seemingly obvious cases should give us faith that their responses in contested cases—like NAM and R.J. Reynolds—reflect more than mere noise.

[55]. See, e.g., Dan M. Kahan et al., “They Saw a Protest”: Cognitive Illiberalism and the Speech-Conduct Distinction, 64 Stan. L. Rev. 851 (2012) (finding that respondents’ perceptions of a video of a protest varied dramatically depending on their political beliefs and what they were told the protest was about).

[56]. The opinion in R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012), prompted a sharply worded dissent, see id. at 1230 (Rogers, J., dissenting), a split with the Sixth Circuit, see Discount Tobacco City & Lottery, Inc. v. United States, 674 F.3d 509 (6th Cir. 2012), and a flurry of academic criticism, see, e.g., Nathan Cortez, Do Graphic Tobacco Warnings Violate the First Amendment?, 64 Hastings L.J. 1467, 1499 (2013). The NAM opinion, although recently issued, has already drawn a successful petition for rehearing, Order for Rehearing, NAM, 748 F.3d 359 (No. 13-5252), and outside attacksfrom popular media, see, e.g., Matt Levine, The First Amendment Lets Companies Keep Quiet About Blood Diamonds, Bloomberg (Apr. 14, 2014), http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2014-04-14/the-first-amendment-lets-companies-keep-quiet-about-blood-diamonds [http://perma.cc/2CRF-F7EY], and academics, see, e.g., Lucien J. Dhooge, The First Amendment and Disclosure Regulations: Compelled Speech or Corporate Opportunism?, 51 Am. Bus. L.J. 599, 602–03 (2014) (characterizing NAM as “an overreach” that could “have significant negative consequences for government regulation”).

[57]. 748 F.3d at 371.

[58]. 696 F.3d at 1217.

[59]. See Dan M. Kahan et al., Whose Eyes Are You Going To Believe? Scott v. Harris and the Perils of Cognitive Illiberalism, 122 Harv. L. Rev. 837 (2009).