Segregation in the Galleries: A Reconsideration

Richard Primus*

When constitutional lawyers talk about the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment as applied to questions of race, they often mention that the spectators’ galleries in Congress were racially segregated when Congress debated the Amendment.[1] If the Thirty-Ninth Congress practiced racial segregation, the thinking goes, then it probably did not mean to prohibit racial segregation.[2] As an argument about constitutional interpretation, this line of thinking has both strengths and weaknesses. But this brief Essay is not about the interpretive consequences, if any, of segregation in the congressional galleries during the 1860s. It is about the factual claim that the galleries were segregated.

The idea that the galleries were segregated by race is, I suspect, incorrect as applied to the House of Representatives and oversimplified as applied to the Senate. The image that the assertion about segregated galleries calls to mind for the modern audience is an image shaped by Jim Crow: two galleries, one formally designated for white observers and another formally designated for black (or “colored”) observers. As explained below, however, that arrangement probably did not exist in either house of Congress when the Fourteenth Amendment was debated. But on the Senate side, a different form of racial segregation was at least sometimes practiced. With the caveat that the evidence is not plentiful, I suspect that what constitutional lawyers have misremembered as flat and formal racial segregation in the galleries was actually a more complex and informal phenomenon that had to do not just with race but with the intersection of race and sex.

To be specific: the evidence of which I am aware indicates that when the Fourteenth Amendment was debated, the Senate did have two spectators’ galleries. But the difference between those galleries was not formally a matter of race. Formally, it was a matter of sex: there was a Gentlemen’s Gallery and a Ladies’ Gallery, the latter of which was open not only to “ladies” but also to the gentlemen escorting them. The Gentlemen’s Gallery, for at least some portions of early Reconstruction, was not racially segregated. But during some of the time period when the Gentlemen’s Gallery was open to black men, the Ladies’ Gallery may have been, in practice, a gallery for white spectators only. The racial segregation of the Ladies’ Gallery was likely a matter of informal administrative practice rather than the enforcement of an official rule.

* * *

According to the received account among constitutional lawyers, the Thirty-Ninth Congress, which adopted the proposal that became the Fourteenth Amendment, debated the measure before a racially segregated audience.[3] Different people take different views of the significance of this fact for modern constitutional law,[4] but the fact itself is treated as a historical given. For most of my own career, I uncritically accepted this account.

The evidence for this factual understanding, however, is remarkably thin. As far as I can tell, nearly all of the law-review literature’s invocations of this claim about congressional practice trace back to a single secondary source from 1977, which in turn rests on a single source from the 1860s. The source from 1977 is Raoul Berger’s landmark work Government by Judiciary, which argued that Brown v. Board of Education[5] was contrary to the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.[6] In the course of building his argument that the Thirty-Ninth Congress had no commitment to desegregation, Berger wrote one sentence on the subject of Congress’s audience. That sentence reads as follows: “The Senate gallery itself was segregated, as Senator Reverdy Johnson mordantly remarked.”[7]

As support, Berger cited the Congressional Globe’s record of a speech that Johnson, a Democrat from Maryland and an opponent of the proposed Fourteenth Amendment, made in Congress on February 9, 1866, as the proposal for the Amendment was debated.[8] As recorded, Johnson was arguing that God differentiated between the black and white races and that people have reasonably taken note of that difference.[9] In its rendering of Johnson’s argument, the Globe records two sentences on the subject of segregation in Congress itself, as follows: “Why is that separate places for the respective races even in your own Chamber? Why are they not put together?”[10] (The syntax of the first sentence seems awkward, but so it appears in the Congressional Globe.)

Berger read those two sentences to indicate that the spectator galleries were segregated by race. On its face, that’s a sensible reading. Later writers followed Berger on the point. When the authors of law-review articles in the twenty-first century mention the segregation of the galleries, and if they bother to cite authority, they generally cite either Berger[11] or the page from the Congressional Globe that Berger cited.[12] In short, it seems that the idea that the galleries were segregated while the Fourteenth Amendment was debated largely rests on one assertion by Berger, for whom it rested on no broader foundation than Johnson’s two sentences.

Other things being equal, the fact that a historical claim rests on only two sentences from a single document does not mean that the claim is wrong. One piece of evidence is evidence, after all. But in the present case, the relevant claim is called into question by no less an authority than the Historian of the House of Representatives. In 2013, in a posting on the Historian’s website that seems to have gone largely unnoticed in the constitutional-law world, the Office of the Historian wrote that black visitors were regularly admitted to the House’s spectators’ galleries in 1864 and 1865.[13] The claim is only lightly documented,[14] and strictly speaking it does not conflict with the received wisdom about segregation in the galleries when the Fourteenth Amendment was under discussion. Those debates occurred in 1866 rather than in 1864–1865, and many statements in the law-review literature about segregated galleries are on their face claims about the Senate rather than Congress as a whole—not, I suspect, because of any intuition that the House was different but simply because Berger’s evidence was a statement made specifically in the Senate. But these possible reconciliations of the two claims should not obscure the deeper reality, which is that there is considerable tension between the House Historian’s claim and the common understanding among constitutional lawyers.

I have found it difficult to gather substantial evidence that would clearly adjudicate this dispute (or reconcile the apparently conflicting accounts). On the basis of the evidence of which I am aware, however, the House Historian’s claim seems correct, at least as applied to the House of Representatives, and the House’s galleries seem to have still been desegregated in 1866, when the Fourteenth Amendment was debated. The best evidence beyond the single document that the House Historian cited, so far as I am aware, is from a speech by Representative Aaron Harding of Kentucky, given just two weeks before Johnson’s remark in the Senate. Harding described black attendance in the House’s galleries in stark and bitter terms. In the course of a long argument against what would become Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment,[15] Harding complained that black spectators had lately been only too common in the House galleries. Moreover, he specifically accused black spectators of having prevented white people from watching the proceedings by arriving first and taking possession of the space.[16] If the House had maintained separate galleries for white and black spectators, black spectators would not have taken up space that would otherwise have gone to white spectators. Harding’s harangue accordingly suggests that the same pool of seats was available to both black and white spectators.

In the Senate, too, black spectators seem to have mixed with white spectators in the final years of the Civil War and also when the Fourteenth Amendment was under consideration. Three documents testify to this effect. The first is the Congressional Globe for February 19, 1864. On that day, in the course of opposing a proposal to conscript more black soldiers for the Union Army, Senator Willard Saulsbury of Delaware argued that it should be plain enough that a Union victory would benefit black persons, such that no further inducements were necessary to recruit black troops. Indeed, Saulsbury said—and not approvingly—the government had made plain the “political Eden” awaiting black persons if the North were victorious.[17] Among other things, the government had signaled the potential for black equality by “throw[ing] open to them the galleries of this Senate, and to-day they sit among the white gentlemen.”[18] The reference to black spectators sitting “among” the whites suggests that the space was not racially segregated.

The second document is from the National Anti-Slavery Standard (i.e., the official newspaper of William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society). In its issue of April 15, 1865, the Standard ran a short story describing a visit by none other than Frederick Douglass to the “once-forbidden seats” of the Senate gallery.[19] According to the story, “Douglass sat in the Senate gallery of the Capitol, thoughtfully scanning the scene below” on “one of the closing days of the last Congress.”[20] The Thirty-Eighth Congress rose on March 3, 1865,[21] so the scene narrated would have taken place about six weeks before the date of publication. It is possible that the report is unreliable: the story, which describes a confrontation between Douglass and a white man “of the ‘old school’ of negro-haters,”[22] reads like it might be urban legend. But maybe the story was accurate. And even if it was embellished, the editors of the Standard would probably not have wanted to run a story that could not possibly be true, and the story they printed places Douglass squarely in a Senate gallery where he would have previously been forbidden to sit. In short, this document seems like reasonable support for the proposition that a Senate gallery once off-limits to black men was no longer so by the time the Civil War ended.

What, then, could have been the basis of Reverdy Johnson’s remark about racial segregation in the Senate galleries when the Fourteenth Amendment was debated?

The answer, I suspect, is inferable from the third document: an article that ran in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper on February 1, 1868. This story describes the two galleries in the Senate chamber: the Gentlemen’s Gallery[23] and the Ladies’ Gallery.[24] The maintenance of separate galleries for ladies and gentlemen was a relatively recent development. Before 1860, the Senate met in what is now called the Old Senate Chamber, and there was just one gallery for spectators.[25] That gallery was not particularly fancy or comfortable, and not everyone who sat there to observe the proceedings was genteel. One writer in 1858 captured the scene this way:

The accommodations in the Senate galleries are so mean that many are deterred from going into them, but on extraordinary occasions they are sure to hold a brilliant collection of Washington ladies . . . . The dress display [on those occasions] is often nearly equal to that of a first-class party, but the fact that these ladies are quite likely to sit next a man in rags [sic] detracts somewhat from the pleasure of the occasion.[26]

In 1859, however, the Senate moved into a new chamber with significantly better accommodations. Among other things, the new chamber featured a separate gallery from which “ladies” (the term is used advisedly) could observe the proceedings without having to sit with male strangers who might be “gentlemen” only as a matter of polite address.[27]

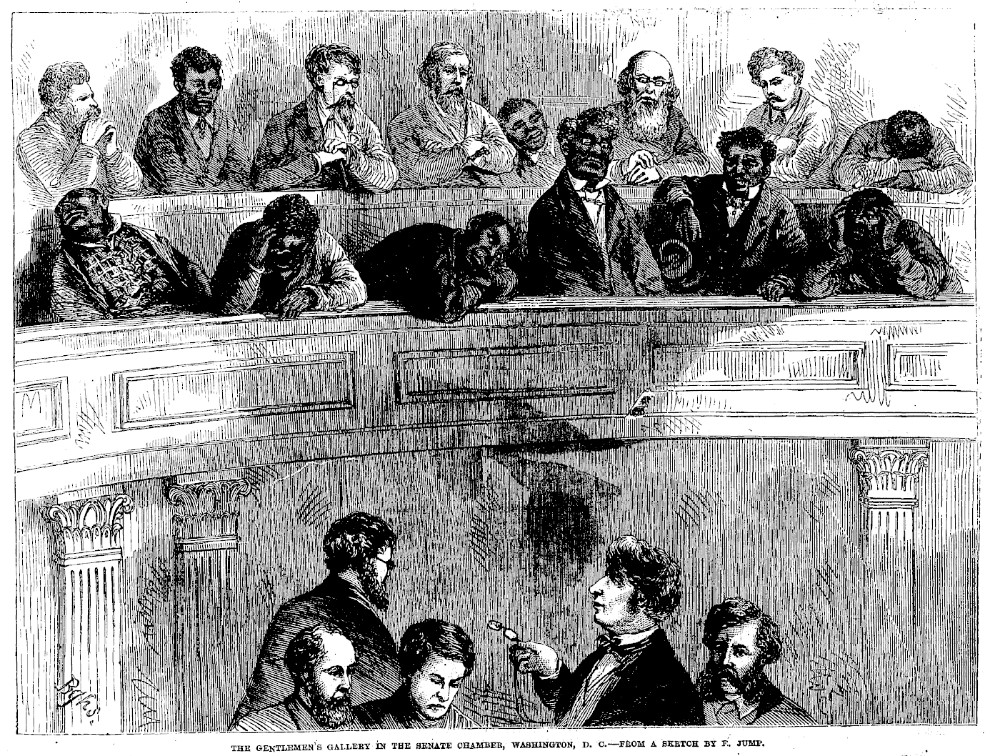

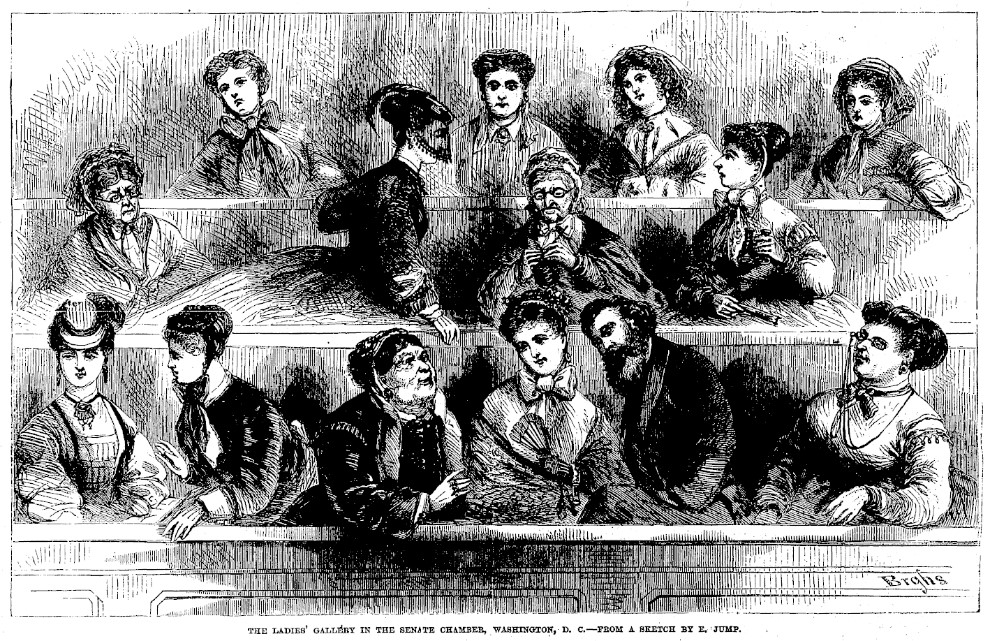

The 1868 story in Leslie’s noted a racial difference between the two galleries.[28] In the Gentlemen’s Gallery, white men and black men sat together.[29] But in the Ladies’ Gallery, “[t]he colored person is not to be found.”[30] Reinforcing this point, the story was accompanied by two illustrations, one of each gallery, made from a reporter’s sketches. The picture of the Ladies’ Gallery shows only white women,[31] but the picture of the Gentlemen’s Gallery shows both black men and white men. In two cases, a black man is shown sitting between two white men, thus making clear that, at least as this document related matters, the Gentlemen’s Gallery did not contain separately designated seating areas for men of different races. In short, the Gentlemen’s Gallery at the relevant time was not racially segregated, but the Ladies’ Gallery was.

Why did only white spectators occupy the Ladies’ Gallery? The newspaper account puts it down to black women’s lack of interest in legislative affairs,[32] but that hardly seems like a satisfactory explanation. (And not only because Saulsbury in 1864 said—indeed, complained—that black spectators appeared in the Ladies’ Gallery almost every day.[33]) A more likely answer, I suspect, has to do with the social status of being a “lady”—and the mechanisms for policing it.

During the nineteenth century, separate spaces for “ladies” in places of public accommodation were commonly understood to be not for women as such but for women of a certain social status.[34] Often, that social status was generally if not officially reserved for white women.[35] The resulting arrangement, whereby a place of accommodation for “ladies” was in practice a place of accommodation for white women, will be familiar to students of nineteenth-century history from contexts like stagecoaches and railroad cars.[36] In all of these contexts, the designation of special “ladies’” areas functioned to prevent “respectable” white women from having to interact with lower-class male strangers—and, at least as importantly, to prevent fraternization between black men and white women.[37] (Indeed, the Ladies’ Galleries in Congress, like ladies’ cars on trains, were not categorically off-limits to men. They accommodated ladies, and also the specific gentlemen escorting those ladies, while screening out more undesirable sorts.[38])

According to the best information I have been able to find, the seating practices in the congressional galleries throughout this period were not governed by formal rules but instead managed informally by the doorkeepers.[39] It is easy to imagine that the doorkeepers exercised some racial discretion on the question of who was, and who was not, a lady, even in the absence of a rule formally establishing racial segregation.

Suppose, then, that we try to take all of the primary sources discussed here as true. What picture emerges? There is more than one possibility, and we cannot know for sure. But on the understanding that I do not claim to prove the hypothesis correct, I will offer the resolution that seems to me most plausible.

At some point during the Civil War, congressional doorkeepers began admitting black visitors to the spectators’ galleries—including, at least some of the time, the Ladies’ Galleries. But the doorkeepers’ practices were not governed by formal rules. Different doorkeepers might have had differing attitudes, and the prevailing regime might have changed from time to time. Black men were consistently admitted to the Gentlemen’s Gallery,[40] but there may well have been stretches of time, pursuant to the ideas of the doorkeepers of the moment, when the Ladies’ Gallery was a whites-only accommodation—and was generally understood to be so. Perhaps the first months of 1866 were such a time, at least on the Senate side. If so, then even though the Ladies’ Gallery was not officially segregated by race, Johnson and his audience would have recognized its racially segregative function. That would have made it sensible for him to say that in the Senate Chamber, spectators were separated by race. And then sometime later, after Reconstruction waned, the practices changed, and segregation hardened, and spectators were officially segregated by race until the decline of Jim Crow in the twentieth century.

Maybe that isn’t the right explanation. Maybe the account of Douglass in the Senate gallery is apocryphal. Or maybe there was a brief moment in 1865 when black gentlemen could sit in the “once-forbidden seats,” but by the beginning of 1866 racial segregation had been officially established, and then there was another thaw by early 1868, as reflected in the pictures from Leslie’s, followed by another official resegregation sometime later. If that’s what happened, then the prevailing reading of Johnson’s statement would be correct, as applied to the specific moment when the Fourteenth Amendment was debated in the Senate. I think this possibility is less likely, for several reasons—including that if there were separate Ladies’ and Gentlemen’s Galleries, the arrangement that the prevailing reading imagines would have required four separate galleries rather than just two. (Or at least three, if, as one might imagine, black women were not afforded the privilege of a gallery where they could sit apart from lower-class black men.) So my best guess, for what it is worth, is that Johnson’s reference to racially segregated galleries referred only to the arrangements then prevailing, informally but significantly, for the Ladies’ Gallery.

* * *

Given my views about constitutional interpretation, I do not think this understanding of congressional practice in the 1860s has any direct consequences for the correct application of the Fourteenth Amendment in later centuries.[41] Instead, the value of this excursion lies in its suggestive reminders about the role of sex in the history of racial segregation, about the role of informal decisionmaking in constitutional spaces, and about the need to resist the tendency to imagine that the arc of history is one of continuous progress, from the moral point of view of the present. (To recognize that the congressional galleries were not segregated at various points in the 1860s is to remember that the relevant authorities were capable of choosing segregation after desegregation had been achieved.[42]) There is also cautionary value in remembering that constitutional discourse tends to oversimplify the complexities of historical practice. And finally, there is the simple value of getting the story right—or, failing that, then as right as possible, while remaining conscious that we may still be missing something significant.

*Theodore J. St. Antoine Collegiate Professor, The University of Michigan Law School. Thanks to Cade Boland, Jamal Greene, Kurt Lash, Virginia Neisler, Nell Painter, Anna Searle, Rebecca Scott, and Adam Wallstein.

[1]. See, e.g., Geoffrey R. Stoneet al., Constitutional Law 490 (8th ed. 2018) (“[T]he spectators in the gallery listening to the senators debate the fourteenth amendment were segregated by race.”); Akhil Reed Amar & Jed Rubenfeld, A Dialogue, 115 Yale L.J. 2015, 2017 (2006) (referring to the segregated galleries at the time of the Fourteenth Amendment); Michael Kent Curtis, The Fourteenth Amendment: Recalling What the Court Forgot, 56 Drake L. Rev. 911, 992 (2008) (“The galleries of the Senate were segregated when the Fourteenth Amendment was passed.”); Jamal Greene, The Anticanon, 125 Harv. L. Rev. 379, 413 (2011) (“The Congress that debated the Fourteenth Amendment did so in front of segregated galleries that remained so into the 1960s.”); David A. Strauss, Not Unwritten, After All?, 126 Harv. L. Rev. 1532, 1543 (2013) (reviewing Akhil Reed Amar, America’s Unwritten Constitution: The Precedents and Principles We Live By (2012) (“[T]he Senate galleries that heard the deliberations were segregated.”).

[2]. See Amar & Rubenfeld, supra note 1, at 2018 (describing “racial segregation in congressional galleries” as part of “the evidence that everyone cites . . . against the notion that the Fourteenth Amendment’s framers believed that the principles of equality and citizenship lying behind it required an abolition of racial segregation”).

[6]. Raoul Berger, Government by Judiciary: The Transformation of the Fourteenth Amendment 117–33 (1977).

[7]. Id. at 125. Berger repeated this claim later in his career. See, e.g., Raoul Berger, The “Original Intent”—as Perceived by Michael McConnell, 91 Nw. U. L. Rev. 242, 254 (1996).

[11]. See, e.g., Peter J. Smith, Originalism and Level of Generality, 51 Ga. L. Rev. 485, 500 (2017); see alsoStone et al., supranote 1, at 490; Stephen A. Siegel, The Federal Government’s Power to Enact Color-Conscious Laws: An Originalist Inquiry, 92 Nw. U. L. Rev. 477, 549 & n.450 (1998).

[12]. See Curtis, supra note 1, at 992 n.371; Michael Kent Curtis, Reflections on Albion Tourgée’s 1896 View of the Supreme Court: A “Consistent Enemy of Personal Liberty and Equal Right”?, 5 Elon L. Rev.19, 62 n.241 (2013) (citing Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 766 (1866)). Greene is the sole exception of which I am aware. He attempted to verify the account independently. See Greene, supra note 1, at 413 n.197 (citing correspondence with House and Senate historians).

[13]. Whereas: Stories from the People’s House: Were There Any Witnesses? Segregation in the House Visitors’ Gallery, Hist., Art & Archives (Apr. 9, 2013), https://history.house.gov/Blog/2013/April/4-03-Gallery-Segregation/ [https://perma.cc/Y2VH-DE7M].

[14]. The relevant text in the post is as follows: “Newspaper reports from as early as 1864 describe black and white visitors sitting together in the House galleries. By the time the 13th Amendment passed the House in 1865, desegregated galleries had been a common sight in the House for almost a year.” Id. The post cites only one source supporting that proposition. The source, an 1864 article from a Cleveland newspaper, is cited without explanation, but it is fairly read to indicate that the House’s galleries were not segregated. On April 13, 1864, a writer in the Cleveland Daily Plain Dealerrelayed a report about the “checkerboard”—that is, black and then white and then black and then white—nature of the Ladies’ Gallery in the House of Representatives. (Ladies’ Galleries, as will be further discussed infra, were generally open to women, or to women of a certain social class, and also to the gentlemen escorting them.) The report’s description of black spectators being seated in that space was disapproving. See Cleveland Daily Plain Dealer, Apr. 13, 1864, at 2.

[16]. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 449 (1866). Harding, a Democrat from Kentucky, analogized the black spectators’ taking possession of the space and thus excluding white spectators to the Republicans’ having excluded Representatives from southern states from Congress. Id. (“At an early hour they rushed into the galleries, ousted and kept out white men and white ladies. . . . They took the galleries just as you have taken this House; you got in first and took possession of this Hall, and when the members from Tennessee and other States came you closed the doors upon them.”). It was not a complimentary comparison.

[23]. The Gentlemen’s Gallery in the Senate Chamber, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (N.Y.), Feb. 1, 1868, at 312.

[24]. The Ladies’ Gallery in the Senate Chamber, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (N.Y.), Feb. 1, 1868, at 312.

[25]. Our Washington Correspondence, FrankLeslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (N.Y.), Dec. 18, 1858, at 37.

[28]. History of the Old Senate Chamber, Architect Capitol, https://www.aoc.gov/history/old-senate-chamber [https://perma.cc/BB5E-M5H3].

[31]. It also depicts one white man. As noted infra text accompanying note 38, Ladies’ Galleries admitted both ladies and the gentlemen escorting them.

[34]. See, e.g., Barbara Y. Welke, When All the Women Were White, and All the Blacks Were Men: Gender, Class, Race, and the Road to Plessy, 1855–1914, 13 Law & Hist. Rev. 261, 261 (1995).

[36]. See, e.g., Kenneth W. Mack, Law, Society, Identity, and the Making of the Jim Crow South: Travel and Segregation on Tennessee Railroads, 1875–1905, 24 Law & Soc. Inquiry 377, 382 (1999).

[37]. See, e.g., Welke, supra note 34, at 280; see also Nell Irvin Painter, Southern History Across the Color Line 112 (2002) (“‘Social equality’ meant associating as equals, which, according to the logic of the slogan, would lead inexorably to black men’s marrying white women.”).

[38]. As noted supra note 31, the 1868 illustration in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper showed a white man sitting with the white women in the Ladies’ Gallery.

[39]. Email from Katherine Scott, Assistant Historian, U.S. Senate Historical Office, to Melissa Lerner (Oct. 12, 2010) (on file with author).

[40]. Whether all black men or just those who seemed to have a certain social status were then eligible for admission is not something that one can guess from these sources.