Prosecutors Matter: A Response to Bellin’s Review of Locked In

John F. Pfaff*

In this year’s Book Review issue, Jeffrey Bellin reviews my book, Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform, and he finds much to disagree with.[1] I appreciate the editors of the Law Review providing me with the opportunity to correct a significant error he makes when discussing some of my data.[2] In the book, I use data from the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) to show that prosecutors filed increasingly more felony cases over the 1990s and 2000s, even as crime fell. Bellin makes two primary claims about how I used this data. The first critique is that I overlooked a fundamental change in how the data was gathered starting in 2003, and the second is that I ignore small, on-going changes in the data over the whole sample period.[3] I can summarize my reply succinctly: the first claim is simply wrong, and while the second concern raises a point worth considering, its impact is far more minor than Bellin’s Review suggests.

In this brief Essay, I will address both of Bellin’s concerns, as well as point to some other data that acts as outside confirmation for the general results that I have found.

I. Some Confusion Over Data Revisions

A central claim in my book is that prosecutors played an outsized role in driving up prison populations, especially in the 1990s and 2000s.[4] Looking at NCSC data on felony filings in state courts over the years 1994 to 2008, I reported that those filings rose even as crime and arrests fell, and that this increase in filing decisions was central to driving mass incarceration during this time.[5] In Part II of his Review, however, Bellin argues that this finding is not real; he claims that the NCSC changed how they measured “felony filings” in 2003 and that my results reflect a change in the data, not a change in prosecutorial behavior.[6]

Bellin points out, correctly, that starting in 2003 the NCSC changed how it gathered its felony-filing data, leading to a discrete jump in the number of felony filings.[7] What Bellin does not mention, however, is that despite making the change in 2003, the NCSC worked to adjust its data back to 1994.[8] In other words, the data from 1994 onwards now use the post-2003 definition of “felony case,” and thus any differences over that time are not due to the 2003 revision.[9] Such retrofitting of data is by no means rare or unprecedented; agencies frequently try to extend changes back in time to minimize the impact of methodological shifts.[10] Bellin’s insistence that 2003, not 1994, is the relevant breaking point in the data is thus incorrect.[11]

In Bellin’s defense, this error likely arose from how the NCSC stores its caseload data. The data exist in three formats: published pulp-and-glue (and now PDF) books, online at the University of Michigan’s giant ICPSR data warehouse, and internally on an Excel spreadsheet. Problematically, only one of those sources, the internal spreadsheet, has the data corrected back to 1994.[12] Obviously, the books published prior to 2003 using the old metric retained the old metric. And the files stored at ICPSR, which are uploaded each year, have not been replaced with revised data, so the pre-2003 data-files, even those for post-1994 years, still use the old definition.[13]

In other words, it is certainly possible that someone using the NCSC data could fall into the trap that Bellin identified, had they used the data from the books or from ICPSR. When I first started using the NCSC data, however, I reached out to those who maintain the data to make sure I understood how it worked, and they sent me their internal spreadsheet.[14] I have to assume that when Bellin’s contacts at the NCSC said that I had overlooked the 2003 break in the data, it was because they did not know which version of the data I had.[15]

Moreover, it should be highlighted that at no point in his review does Bellin show that my results are compromised by the problem he believes he has identified; he simply suggests it. Given that the NCSC data is publicly available, Bellin could have verified that this problem existed, or asked me to share the NCSC data I had with him so he could have checked it himself. He makes an easily-testable critique without actually testing it,[16] but then frames it as showing that my results are in fact driven by what he purports to have uncovered.[17]

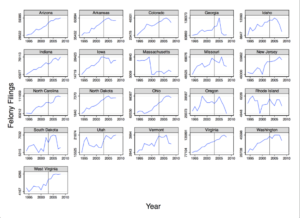

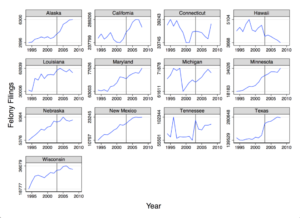

As it is, a quick look at the data demonstrates that there is no dramatic shift in 2003.[18] Figures 1A and 1B plot the felony caseload data for the states I used over the period 1994-2008.[19] Figure 1A plots caseloads for what I called the “Tier A” states in the original study,[20] which are the states whose filing data seemed to exhibit the fewest idiosyncratic jumps and whose NCSC data often lined up closely with other sources of state court data. Figure 1B plots caseloads for the “Tier B” states, which are states whose data seemed less clean but not so problematic that I decided to drop them altogether.[21] If Bellin’s claims were correct, we should expect to see a significant jump right at 2003 (the vertical line in each graph).

Fig. 1A

Fig. 1B

It’s clear from Figures 1A and 1B that Bellin’s concerns do not hold up. Almost no states show any sort of clear break in 2003: without the vertical line on the graphs, it would be nearly impossible to guess where “2003” was on any of them. A few states (Utah in Figure 1A and Tennessee in Figure 1B) experience large increases a year or so prior to the change, but not at the time when Bellin alleges that the data series experienced its break.[22] The one exception is Texas, which does see a sharp rise then, and is thus the one case where the change that Bellin identifies appears to have mattered.[23] With hindsight, I should have omitted Texas.[24] That said, when I rerun the models without Texas, the results do not change appreciably.[25]

II. Minor Shifts in Data Quality

Bellin’s second critique is not as clearly incorrect as his first one, but whatever impact it has is surely quite minor. Bellin points out, again correctly, that the NCSC cautions users of its caseload data that it is continuously trying to improve the completeness of the data it gathers.[26] Such improvements will almost always increase the number of cases reported—it is likely that some courts do not report at first, but harder to imagine cases where the problem is a courthouse reporting more cases than it actually has. Thus, some increase in felony filings could reflect general improvements in reporting, even independently of any change in 2003 (or 1994).

I have two specific replies to this critique. The first is that while the data guide cautions about continuous improvements, the NCSC analyst with whom I communicated the most did not see this as a major concern. I checked more than once with her to make sure that comparing across states and across years within the 1994-2008 period was methodologically sound, and she asserted that it was.[27] The second is that it is unlikely that improvements would be smooth and continuous: we should expect improvements to manifest themselves as discrete jumps in the data as the quality improves in one year, and that these jumps would happen at different times across the states. Look again, however, at Figures 1A and 1B. Rarely do we see that sort of step-wise jump. It seems far more likely that the relatively smooth rise in filings seen across a wide range of states reflects a common behavioral shift rather than a change in data quality. Moreover, several states see their filings decline by the end, which is particularly inconsistent with data collection improvements that lead to increases in felony cases reported.[28]

III. Outside Verification: The State Court Processing Statistics and the National Judicial Reporting Program

As Bellin points out in his Review, in my work I not only look at the NCSC data but also at a dataset on felony cases gathered by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) called the State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS).[29] Intriguingly, the SCPS shows far less of a rise in felony filings than the NCSC data.[30] I suggest in one paper that this may reflect the more-limited reach of the SCPS, which examines a smaller number of jurisdictions.[31] Bellin, however, argues that this reinforces the idea that my NCSC results are faulty, and he states that his contacts at the NCSC told him they would trust the SCPS data over the NCSC’s.[32]

I disagree, for two reasons. To start, the SCPS is a somewhat quirky dataset. It is, for example, the only BJS dataset I have encountered that comes with an explicit warning about not using parts of it in causal analyses.[33] It also gathers its data in a rather idiosyncratic way. It looks just at populous counties, not states in their entirety, and it gathers the data by collecting information on cases filed on random days in May every other year and then tracking those cases for the next year or until resolution.[34] My own experience with the dataset has made me cautious about how much to rely on it, and in informal conversations colleagues have expressed similar concerns.

Reinforcing my concerns with trusting the SCPS over the NCSC data is that the BJS gathers a second dataset on felony case outcomes in state courts, the National Judicial Reporting Program (NJRP), that produces results almost identical to those I find using NCSC data.[35] Importantly, the BJS gathers the NJRP in a much different way than the NCSC data, so it acts as an independent check on my NCSC claims. The NJRP collects data from a nationally-representative sample of 300 counties biannually (a much wider geographic range than the SCPS) on all felony sentences imposed in those counties that year.[36] Sentences, of course, are not the same thing as case filings, but perhaps about two-thirds of all felony arrests and a much larger percentage of all felony prosecutions result in guilty verdicts (and thus felony sentences), so the NJRP tracks data that is analogous, although not identical, to what the NCSC measures.[37]

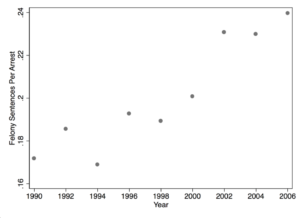

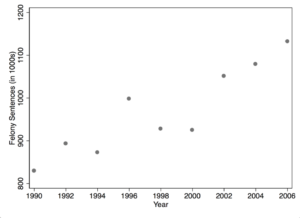

In other words, the NJRP, which is gathered by a different institution using different methodologies, provides an external check on my findings—and it yields quite-similar results.[38] Figure 2A plots the trends in NJRP guilty verdicts, and Figure 2B plots the felony sentences per arrest ratio. The core claim in my book is that both total felony filings as well as felony filings per arrest rise sharply, and the NJRP trends for both track those I derived from the NCSC data.[39] Between 1990 and 2006, guilty verdicts rise by 36%[40]—which is nearly identical to the approximately 37% rise I find in the NCSC data between 1994 and 2008.[41] And the fraction of arrests that result in a guilty verdict rises by about 40% between 1990 and 2006, which is comparable (if slightly lower) than the 50% rise seen using the NCSC data between 1994 and 2008.[42]

Fig. 2A

Fig. 2B

Conclusion

As I hope this brief note makes clear, Bellin’s critique of my data on prosecutorial filing behavior is incorrect. Given that the NCSC has multiple versions of its data, some of which change in 2003 and others in 1994, the error is understandable. But as Figures 1A and 1B make clear, the data clearly support my claims about the trends in felony filings. I hope that the clarity of Figures 1A and 1B, along with the confirming evidence from the NJRP in Figures 2A and 2B, makes it clear that there really was a change in prosecutorial behavior during the 1990s and 2000s, and that this change was significant and important.[43]

Not surprisingly, an argument that runs as contrary to the conventional wisdom as mine has generated significant push-back, and I am sure that the various rebuttals that have been offered will help me produce an even more nuanced take on the drivers of mass incarceration.[44] But nothing I have seen so far has convinced me that prosecutors are not the central actors here (even if they are not the sole cause of prison growth), or that their behavior did not change significantly over this time.

*Professor of Law, Fordham University School of Law. All errors are my own.

[1]. John F. Pfaff, Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform (2017); Jeffrey Bellin, Reassessing Prosecutorial Power Through the Lens of Mass Incarceration, 117 Mich. L. Rev. 835 (2018).

[2]. Understandably, the Law Review generally does not permit replies to its book reviews: it would find itself swamped by replies and sur-replies and sur-sur-replies. Bellin’s critique of my data, however, poses a unique problem, because it is not the sort of critique that most readers, even those with a sophisticated understanding of the criminal justice system, can evaluate on their own. And to be clear, that my focus is just on Part II of Bellin’s Review should not be read to mean I agree with the rest of the criticisms.

[3]. See Bellin, supra note 1, at 837.

[4]. Pfaff, supra note 1, at 206.

[6]. Bellin, supra note 1, at 843.

[8]. Email from Shauna M. Strickland, Senior Court Research Analyst, Research Div. Nat’l Ctr. for State Courts, to John Pfaff, Professor of Law, Fordham Univ. Sch. of Law (July 12, 2011, 02:10 PM EST) (on file with the Michigan Law Review).

[9]. Id. There is one exception, however: as we will see below, Texas experienced a distinct rise in 2003.

[10]. In 2010, for example, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) completed a major redesign of its National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP) dataset. As part of the project, the BJS did not just change how it gathered NCRP data going forward, but spent considerable effort gathering the information needed to extend the new approach back to 2000. See William Rhodes et al., Abt Associates, The NCRP Data as a Research Platform: Evaluation Design Considerations (May 28, 2015)(draft), http://www.ncrp.info/LinkedDocuments/NCRP%20as%20a%20research%20platform.5%2028%202015.pdf [perma.cc/ZK33-DMKW].

[11]. For example, Bellin explicitly states: “Pfaff starts with 1994, he writes, because the NCSC ‘changed the way it gathered data in 1994’ preventing comparison to earlier years. As noted above, the NCSC actually changed its data gathering rules in 2003.” Bellin, supra note 1, at 841 n.34. While Bellin is right that the methodological shift occurred in 2003, the data shift starts in 1994.

[12]. Telephone Interview with Shauna M. Strickland, Senior Court Research Analyst, Research Div. Nat’l Ctr. for State Courts, (March 10, 2017).

[14]. See Strickland Email, supra note 8.

[15]. Bellin sent me a copy of his Review a few days before posting it to SSRN. I explained my data sources to him at that point and in later emails, but he did not change his Review to reflect this new information. E-mail from John Pfaff, Professor of Law, Fordham Univ. Sch. of Law, to Jeffrey Bellin, Professor of Law, William & Mary Law Sch. (Mar. 8, 2017, 11:15 EST) (on file with the Michigan Law Review); E-mail from John Pfaff, Professor of Law, Fordham Univ. Sch. of Law, to Jeffrey Bellin, Professor of Law, William & Mary Law Sch. (Apr. 25, 2017, 02:32 EST) (on file with the Michigan Law Review). See Jeffrey Bellin, Reassessing Prosecutorial Power Through the Lens of Mass Incarceration, 117 Mich. L. Rev. (forthcoming Apr. 2018), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2930116 [https://perma.cc/Z65U-2XJY].

[16]. See Bellin, supra note 1, at 843–48. There are some empirical critiques that cannot be tested, and in these situations focusing on the more theoretical concerns is legitimate. But these issues are almost always methodological, like asking whether some set of unavoidable assumptions is reasonable. The issue here is whether the data made a distinct jump in 2003, something that even Excel can easily demonstrate.

[17]. Consider, for example, the certainty of this claim: “In sum, changes in reporting practices, alongside a natural spread of voluntary collection efforts, would inflate reported filings during the period Pfaff analyzed, even if the actual number of filings hardly budged.” Bellin, supra note 1, at 843.

[20]. The empirical claims I make in Locked In— which is a trade-press book aimed at the general public— are all developed more rigorously in prior empirical papers. My claims about prosecutors are developed in John F. Pfaff, The Micro and Macro Causes of Prison Growth, 28 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. 1237 (2013)[hereinafter Prison Growth]; John F. Pfaff, The Causes of Growth in Prison Admissions and Populations (Jan. 24, 2012)(unpublished article) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1990508 [https://perma.cc/Z65U-2XJY].

[21]. Including the Tier B results, which I do to provide a more comprehensive picture, actually weakens my findings by a small amount. The Tier A states alone see an increase of 40% in filings, but the Tier A and Tier B states collectively see a rise of 37%. When it comes to the percent of arrests resulting in felony cases, adding in Tier B has almost no impact: for Tier A alone, the risk rises from 38% to 59% over the sample period, while including Tier B yields a change from 37% to 57%.

[22]. Supra figs.1A & 1B; Bellin, supra note 1, at 842–43.

[23]. Supra fig.1B; See Katherine Beckett, Mass Incarceration and Its Discontents, 47 Contemp. Soc. 11, 19 n.14. Beckett provides evidence that Florida and Texas changed the way they provided information in 2003 in ways that limited the NCSC’s ability to adjust the data back to 1994. Florida is immaterial to this discussion, because I excluded it from my study due to data concerns.

[24]. I included Texas because it had experienced striking short-run increases in other criminal justice metrics in the past. Its prison population, for example, grew by about 6% per year from 1978 to 1991, then by 17% in 1992, and then by a remarkable 52% in 1993 and 28% in 1994. Thus, a jump that would have almost certainly excluded any other state was not entirely implausible in Texas.

[25]. Including Texas, the Tier A and Tier B states see a 37% rise in filings; excluding just Texas reduces that to 32%. Of course, eliminating Texas has no impact on the estimated 40% rise for Tier A states, since it was in Tier B from the start. Moreover, dropping Texas has almost no impact at all on the estimate of the percent of arrests resulting in a felony charge (with Texas, the increase is from 37% to 57%, while without it is from 37% to 56%).

[26]. Bellin, supra note 1, at 842.

[27]. Strickland Interview, supra note 12; Strickland Email, supra note 8; Email from Shauna M. Strickland, Senior Court Research Analyst, Research Div. Nat’l Ctr. for State Courts, to John Pfaff, Professor of Law, Fordham Univ. Sch. of Law (Apr. 20, 2017 10:17 AM EST) (on file with Michigan Law Review).

[29]. See Bellin, supra note 1, at 842 (claiming SCPS data contradicts Locked In’s conclusion).

[30]. See Data Collection: State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS), Bureau Just. Stat., (2009) https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=dcdetail&iid=282 [https://perma.cc/J5F4-JH9D] [hereinafter SCPS].

[31]. See Pfaff, The Causes of Growth in Prison Admissions and Populations, supra note 20.

[32]. Bellin, supra note 1, at 843.

[33]. Compare Nat’l Ctr. for State Courts (NCSC), State Court Guide to Statistical Reporting (2003), http://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/ctadmin/id/1229 [https://perma.cc/M9LZ-M7CH] [hereinafter NCSC], with NJRP, infra note 35.

[34]. See, e.g., State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS), 1990-2009: Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, Bureau Just. Stat., (Jun. 24, 2014) [hereinafter SCPS 1990-2009] https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACJD/studies/2038. [https://perma.cc/2TBN-EE83].

[35]. Data Collection: National Judicial Reporting Program (NJRP), Bureau of Just. Stat., U.S. Dep’t of Just., (2006) https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=dcdetail&iid=241 [https://perma.cc/3A3N-FRU3] [hereinafter NJRP].

[37]. For arrest-to-conviction data, see Thomas H. Cohen & Tracey Kyckelhahn, Bureau of Just. Stat., U.S. Dep’t of Just., Felony Defendants in Large Counties, 2006 fig.1 (2010) https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fdluc06.pdf [https://perma.cc/N888-ZHTA], and Brain A. Reaves, Bureau of Just. Stat., U.S. Dep’t of Just., Felony Defendants in Large Counties, 2009 tbl.21 (2013) https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fdluc09.pdf [https://perma.cc/9DRE-V2DV]. To be completely transparent, these values come from the SCPS, with all the limitations that entails, and the most recent data here is from 2009, which is when the SCPS was last conducted.

[38]. Cf. NJRP, supra note 35 with NCSC, supra note 33.

[39]. See Pfaff, supra note 1, at 69–72; NJRP, supra note 35. In both Locked In and here, I focus on arrests for violent, property, and non-marijuana drug arrests, since so few marijuana cases end up in prison. See John F. Pfaff, The War on Drugs and Prison Growth: Limited Importance, Limited Legislative Options, 52 Harv. J. on Legis. 174, 205 fig.4A.

[40]. See NJRP, supra note 35.

[41]. See Prison Growth, supra note 20.

[42]. It is worth nothing that the levels differ between the two datasets. The NCSC study suggests that about 33% of arrests produce a felony case, versus 17% producing a felony sentence using the NJRP. See supra, figs.1A & 1B. If nothing else, this surely reflects the fact that there will be fewer guilty verdicts than felony cases. Given the inherent noisiness of criminal justice data, however, that the various measures move in the same direction is likely more relevant than the particular starting levels, especially since the focus here is on the impact of the change in behavior.

[43]. See supra, Part I, figs.1A & 1B; supra Part III, figs.2A & 2B.

[44]. If nothing else, any sort of “this is what happened in the US” story inevitably paints with too broad a brush. The criminal justice system varies greatly across and within states, and no explanation applies with equal force everywhere. I am starting to explore this in more detail for future work. For example, I’ve come to appreciate that while my data show that the risk of a felony case producing a prison admission remained stable at the national level between 1994 and 2008, see SCPS 1990-2009, supra note 34, there was a fair amount of state-level variation, which suggests other ways that prosecutorial discretion may operate. See NCSC, supra note 33. It may also point to ways that legislative and other changes influenced that discretion—although given the nature of laws passed during my sample period, almost none of which aimed to rein in punitiveness, it is unlikely that legislative actions often limited prosecutorial options (See, e.g., Beckett et al., The End of an Era? Understanding Contradictions of Criminal Justice Reform, 644 Annals Am. Acad. Pol. & Soc. Sci. 238 (2016).