The Meaning of Sex: Dynamic Words, Novel Applications, and Original Public Meaning

The meaning of sex matters. The interpretive methodology by which the meaning of sex is determined matters. Both of these were at issue in the Supreme Court’s recent landmark decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, where the Court held that Title VII protects lesbians, gay men, transgender persons, and other sexual and gender minorities against workplace discrimination. Despite unanimously agreeing that Title VII should be interpreted in accordance with its original public meaning in 1964, the opinions in Bostock failed to properly define sex or offer a coherent theory of how long-standing statutes like Title VII should be interpreted over time. We argue that long-standing statutes are inherently dynamic because they inevitably evolve beyond the original legislative expectations, and we offer a new theory and framework for how courts can manage societal and linguistic evolution. The framework depends in part on courts defining ‘meaning’ properly so that statutory coverage is allowed to evolve naturally over time due to changes in society, even if the meaning of the statutory language is held constant (via originalism).

Originalism in statutory and constitutional interpretation typically focuses on the language of the text itself and whether it has evolved over time (what we term linguistic dynamism), but courts should also recognize that the features of the objects of interpretation may also evolve over time (what we term societal dynamism). As society changes, so do social norms; what we call normative dynamism is the influence of evolving values on the interpretive enterprise, however conceptualized. Linguistic and normative dynamism create difficulties for originalism, but societal dynamism should not, as originalists have assumed in other contexts (such as Second Amendment jurisprudence). We explore the relationship among societal, linguistic, and normative dynamism and their implications for original public meaning.

Putting our framework into action, we demonstrate, through the application of corpus analysis and linguistic theory, that sex in 1964 was not limited to “biological distinctions between male and female,” as all the opinions in Bostock assumed, and that gender and sexual orientation were essentially non-words in 1964. Sex thus had a broader meaning than it does today, where terms like gender and sexual orientation (and other terms like sexuality) denote concepts that once could be referred to as sex (on its own and in compounds). In turn, today’s gays and lesbians and transgender people are social groups that did not exist (or that existed in a very different form) in 1964. By limiting the meaning of sex to “biological distinctions” and failing to recognize that societal dynamism can change statutory coverage, the Court missed the opportunity to explicitly affirm that the societal evolution of gays and lesbians and transgender people has legal significance. Finally, the Court missed an opportunity to acknowledge the importance law can assume in societal and linguistic dynamism: one reason gays and lesbians are a novel social group is that they live in a world where same-sex intimacy is not a crime and the state does not treat homosexuality as psychopathic.

Introduction

On June 15, 2020, the Roberts Court set off a minor public law explosion when it handed down its decision in Bostock v. Clayton County.1140 S. Ct. 1731 (2020). The big news was that lesbians, gay men, transgender persons, and other sexual and gender minorities are protected against workplace discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.2 See Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1754. In less than twenty years, these minorities have moved from being outlaws and psychopaths to in-laws with jobs.3 See William N. Eskridge Jr. & Christopher R. Riano, Marriage Equality: From Outlaws to In-Laws (2020). For professors of legislation, history, and linguistics, the headline was that all three opinions in the case—the majority opinion for the 6–3 Court and both dissenting opinions—billed themselves as determining the original public meaning4In this Article, we use double quotes for quotations, single quotes for meanings and concepts, and italics for mentions of words (and for emphasis), as exemplified in the following sentence: The public meaning of run is ‘to go faster than a walk.’ of Title VII’s text, which from 1964 through the present has told employers they cannot “discriminate against any individual . . . because of such individual’s . . . sex.”5Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)(1). Another relevant provision, § 703(m), was added to Title VII in its 1991 Amendments. See Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. 102–166, sec. 107, § 703(m), 105 Stat. 1071, 1075 (codified at 42 U.S.C. 2000e–2). But how do you get from this language focusing on sex to protection of the two gay men and one transgender woman involved in the cases consolidated in Bostock? This was surely beyond the imagination or even the tolerance of legislators in 1964.

Justice Gorsuch’s opinion for the Court focused on the definitions of the key statutory terms—including sex, which he explicitly assumed meant only the biological differences between women and men—and concluded that a man fired for dating men would not have been fired if he were a woman who dated men, and a person identified as male at birth but who now identifies as female would not have been fired had they been identified as female at birth.6 Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1741–42. Thus, the original public meaning of Title VII covered gay and transgender employees. Joined by Justice Thomas, Justice Alito’s dissenting opinion framed the public meaning inquiry as an empirical issue: no one reading the statutory language in 1964 would have thought it protected “gays and lesbians” or “transgender persons,” who were considered immoral, criminal, or, at best, “mental[ly] disorder[ed]” in that period.7 Id. at 1769–73, 1777 (Alito, J., dissenting); see also William N. Eskridge Jr., Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861–2003, at 387–407 (2008) (documenting factual points made in this part of the Alito dissent). Rather, “[t]he possibility that discrimination on either of these grounds might fit within some exotic understanding of sex discrimination would not have crossed the[] minds” of “ordinary Americans.”8 Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1767 (Alito, J., dissenting). In fact, “Americans . . . would have been shocked to learn” that Title VII forbids “discrimination on the basis of ‘transgender status’ or ‘gender identity,’” which are “terms that would have left people [in 1964] scratching their heads.”9 Id. at 1772 (explaining that “transgender” and “gender identity” were not in “common parlance” in the 1960s). Justice Kavanaugh’s dissenting opinion similarly argued that the Court’s opinion “rewrites history” by refusing to acknowledge that “an overwhelming body of federal law . . . demonstrates that sexual orientation discrimination is distinct from, and not a form of, sex discrimination.”10 Id. at 1828–29 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting).

While the justices disagreed about how the public meaning of a legal text should be framed, and what evidence is relevant to its determination, the Bostock Court was unanimous in maintaining that the meanings of all the relevant terms—“discriminate,” “because of,” “individual,” and “sex”—were the same in 2021 as in 1964. Indeed, the notion of “updating” Title VII was anathema to all the justices. One major theme of both dissenting opinions was that the Court was updating Title VII to reflect the current values of society while disingenuously claiming to apply textualist principles,11 Id. at 1756 (Alito, J., dissenting) (arguing that the Court should “own up to what it is doing,” which is “represent[ing] . . . a theory of statutory interpretation that Justice Scalia excoriated—the theory that courts should ‘update’ old statutes so that they better reflect the current values of society”); id. at 1834 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting) (arguing that the Court updated Title VII by “seizing on literal meaning and overlooking the ordinary meaning of the phrase ‘discriminate because of sex.’” (quoting 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–2(a)(1))). which the Court sternly denied.12 Id. at 1738 (majority opinion) (explaining that “[i]f judges could . . . update . . . old statutory terms inspired only by extratextual sources and our own imaginations, we would risk amending statutes outside the legislative process reserved for the people’s representatives”). The thesis of this Article is that the Bostock Court—majority and dissenters alike—overstated the dichotomy between original public meaning and dynamic interpretation.13For a similar project in the context of the Founding and the early Republic, see Farah Peterson, Expounding the Constitution, 130 Yale L.J. 2 (2020).

As we explain in Part I, because super-statutes like Title VII are both transformative and long-standing, interpretive uncertainties arise when they are applied to new, and often unforeseen, circumstances.14Super-statutes are landmark laws that successfully displace common law norms and entrench new transformational legal rules. See William N. Eskridge, Jr. & John Ferejohn, Super-Statutes, 50 Duke L.J. 1215, 1230–46 (2001). Most leading scholars believe such statutes ought to be applied dynamically to carry forth their purposes into modern society. See, e.g., Benjamin N. Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process 81–88 (1921); John Chipman Gray, The Nature and Sources of the Law 170–83 (Roland Gray ed., Macmillan 1921) (1909); Henry M. Hart Jr. & Albert M. Sacks, The Legal Process: Basic Problems in the Making and Application of Law 1111−1210 (William N. Eskridge, Jr. & Philip P. Frickey eds., 1994); Kent Greenawalt, Statutory and Common Law Interpretation (2013); Richard A. Posner, How Judges Think (2008). Experience suggests that whatever the interpretive theory, these long-standing statutes will inevitably be applied dynamically over time. See William N. Eskridge, Jr., Dynamic Statutory Interpretation 48–49 (1994). An original-public-meaning interpreter will also be a dynamic interpreter (even if unconsciously) because statutes must be applied to scenarios that did not exist (and often could not have been imagined) at the time of the statute’s creation. In addition, the objects or concepts to which the statute is applied, rather than the statutory language itself, may also evolve over time. Situations like the two described above—where applying the statute today has different outcomes than applying it when it was enacted, even when the original meaning of the statutory language is unchanged—are examples of what we term societal dynamism. Significantly, these scenarios are distinct from circumstances where the meanings of the statutory words themselves evolve over time, as natural language often does. We label this situation linguistic dynamism and argue that it is as inevitable as the earlier scenarios. Finally, because changes in society and law over time produce new social and even constitutional norms, the application of old statutes to current circumstances often implicates what we label normative dynamism. Linguistic and normative dynamism challenge originalism in ways that societal dynamism does not.

In Part II, we address these three scenarios through analysis of a variation of a famous hypothetical discussed in Bostock, an ordinance we shall (for narrative convenience) situate in 1964: “No vehicles shall be allowed in the park.”15 See Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1825 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting); H.L.A. Hart, Positivism and the Separation of Law and Morals, 71 Harv. L. Rev. 593, 607 (1958). Society since 1964 has evolved in various ways, including technologically. This evolution creates potential interpretive disputes about whether the ordinance applies to mechanisms (such as Segways) that exist in 2021 but did not in 1964.16 See infra Section II.B. (analyzing how the no-vehicles statute should be applied to objects that did not exist at the time of the statute’s enactment). As a matter of language as well as legal logic, a directive using words whose meaning is stable over time is therefore moderately dynamic: it will often apply beyond the expectations of its framers.17 See Daniel A. Farber, Statutory Interpretation and Legislative Supremacy, 78 Geo. L.J. 281, 282–83, 287–92 (1989); cf. William N. Eskridge, Jr., Spinning Legislative Supremacy, 78 Geo. L.J. 319, 324 (1989) (arguing that the “faithful agent” of an open-textured statute will apply it both beyond and against original legislative expectations). Similarly, capturing the second type of societal evolution, the no-vehicles prohibition may apply to mechanisms that did exist but may not have been covered in 1964, if those mechanisms have fundamentally changed since 1964.18 See infra Section II.C. (analyzing how the no-vehicles statute should be applied to objects whose features have changed over time). An example might be new motorized wheelchairs that are much bigger, faster, and more sophisticated than those existing in 1964. Application of the earlier law to something that changed so dramatically might often be a fairly uncontroversial example of statutory updating, beyond but not necessarily against the original expectations or meaning.

The two scenarios above demonstrate the dynamic potential of statutory provisions even without implicating situations where the meanings of the statutory terms have changed over time. But language is dynamic. Words may mean today something quite different than in some earlier period.19 See John R. Taylor, Linguistic Categorization 59−60 (3d ed. 2003) (“[T]he prototype representations of many categories may change dramatically over time. Speakers in 1800, 1900, and 2000 would surely have selected different entities as good examples of the vehicle category, while the prototypical automobiles of eighty years ago are now fairly marginal exemplars of the category.”); see also Jean Aitchison, Language Change: Progress or Decay? 153–54 (Cambridge Univ. Press 4th ed. 2013) (1981) (explaining that “sociolinguistic causes of language change” involve the altering of language “as the needs of its users alter”); Peter Ludlow, Living Words: Meaning Underdetermination and the Dynamic Lexicon 3 (2014) (rejecting “the idea that words are relatively stable things with fixed meanings”); Dirk Geeraerts, Theories of Lexical Semantics 230 (2010) (“[N]ew word senses emerge in the context of actual language use.”). For instance, because so many new motorized conveyances have come on the market since 1964, the meaning of vehicle itself has evolved, evidencing linguistic dynamism.20 See infra Section II.E. (describing how the term vehicle has evolved since 1964). In some of these situations, such as criminal laws where the audience for the statute is itself evolving, compelling reasons may exist for insisting that the statutory language means something different in 2021 than in 1964.21 See Lawrence M. Solan, Law, Language, and Lenity, 40 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 57 (1998) (discussing dynamic interpretation in relation to criminal statutes). A similar phenomenon occurs when the application of old statutes is in tension with new social or constitutional norms. In such situations, the judicial process of accommodating new norms, and thereby producing a dynamic interpretation, is typically unconscious or implicit, although there are no compelling reasons why it must be.22 See William N. Eskridge, Jr., Gadamer/Statutory Interpretation, 90 Colum. L. Rev. 609 (1990) (arguing that statutory interpretation is, in the deepest cases, an occasion for the interpreter to interact with the text and everything coming after the text).

What is our evidence for these assertions? We document our language-based claims with empirical evidence that is vastly superior to the usual dictionary shopping and personal-intuition methods ordinarily deployed by judges. Specifically, we use corpus linguistics to help demonstrate how changes to language and society over time combine to make statutory meaning inevitably dynamic. Corpus linguistics is typically based on “the statistical analysis of data from a corpus,” which is “a [machine-readable] compilation of written and transcribed spoken language used in authentic communicative contexts” (such as in newspapers, novels, books, etc.).23Brief for Amici Curiae Corpus-Linguistics Scholars Professors Brian Slocum, Stefan Th. Gries & Lawrence Solan in Support of Emps. at 7, Bostock v. Clayton Cnty., 140 S. Ct. 1731 (2020) (No. 17-1618). If performed competently, corpus linguistics meets the scientific standards of generalizability, reliability, and validity.24Haoshan Ren, Margaret Wood, Clark D. Cunningham, Noor Abbady, Ute Römer, Heather Kuhn & Jesse Egbert, “Questions Involving National Peace and Harmony” or “Injured Plaintiff Litigation”? The Original Meaning of “Cases” in Article III of the Constitution, 36 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. 535, 540 (2020) (explaining the scientific nature of corpus linguistics). Recently, various academics and judges have argued that corpus linguistics can help judges approach public meaning in a more systematic and objective manner.25 See, e.g., Thomas R. Lee & Stephen C. Mouritsen, Judging Ordinary Meaning, 127 Yale L.J. 788 (2018) (arguing that corpus linguistics can make legal interpretation more empirical). While some of the leading approaches to corpus linguistics in the legal context have serious shortcomings, as we address, corpus linguistics does have the potential to help judges make better, empirically based judgments about how words are used, both today and historically.

Through the application of linguistic theory, we offer three important contributions to a better understanding of the significance of the Court’s movement toward emphasizing original public meaning when interpreting statutes. To begin with, as explained in Part I, Bostock illustrates how statutory interpretation in federal courts has shifted focus away from language production to language comprehension. Given the Court’s movement toward original public meaning, there is now less focus on legislators’ expectations when drafting statutes and more on the understanding and expectations of the public expected to comprehend statutory directives. This is a more important shift than scholars and courts have recognized. Descriptively, the shift demands that judges improve their skills at interpreting texts, and that has created a legal as well as a judicial audience for expert historical analysis and linguistic theory (hence, this Article). The interpretive shift from language production to language consumption has also diminished the importance of congressional deliberation and has marginalized knowledge about the legislative process and how to research legislative history, which have been traditional legal skills since the New Deal.26As this Article partially demonstrates, it appears judges are currently not as good at historical and language analysis as they once were with legislative history analysis (which was uneven at best). See infra Sections I.A, I.B. Normatively, the shift is away from legitimacy based on representative democracy and good governance and toward legitimacy based on a neutral rule of law. The judicial debate in Bostock reflects the Roberts Court’s ongoing efforts to exhibit expertise and neutrality in its application of textual materials to new facts and legal controversies.27Expertise and neutrality in application at least seem to be the central agenda of Neil Gorsuch and John Roberts, two unexpected votes for LGBT rights. The critical analysis in this Article suggests that the Court faces major difficulties when the justices try to identify original public meaning: they do not reveal impressive expertise in language analysis, and the cherry-picked and closeted norms of their historical analyses undermine their aspirations toward neutrality.

A second contribution of our Article, also developed in Part I, is a theoretical grounding for the Gorsuch versus Alito/Thomas/Kavanaugh debate over precisely what original public meaning entails.28For all the justices, the reference point is 1964, which is a mistake considering that Title VII has been amended multiple times. See infra Section III.C.2. Justice Gorsuch takes what linguists might call a more ‘intensional’ approach to meaning, which determines the general concept defining the relevant statutory term and applies it to the objects in question (in Bostock, lesbians, gay men, transgender persons, and other sexual and gender minorities). In contrast, the dissenting opinions take a more ‘extensional’ approach to meaning, which asks what things fall within the statutory category at a certain point in time.29 See infra Section I.B.1 (explaining the distinction between extensional and intensional meaning). Thus, Gorsuch applies the concepts entailed in discriminate and because of and sex to modern gay men, lesbians, and transgender persons—while Alito and Kavanaugh insist that the (empirically based) inquiry must be whether gays and lesbians would have been listed under the ‘sex’ concept in Title VII in 1964. This may be a long-term division within the Court—Gorsuch and Roberts versus Alito, Thomas, and Kavanaugh, with the Court’s more liberal pragmatists still looking at legislative history and purpose.30 Cf. Stuart Minor Benjamin & Kristen M. Renberg, The Paradoxical Impact of Scalia’s Campaign Against Legislative History, 105 Cornell L. Rev. 1023, 1024 (2020) (showing empirically that textualist critiques of legislative history have had the effect of causing some judges “to (re)examine their treatment of legislative history but not . . . to avoid citing it”). Regardless of the methodological division within the Court, we argue that only an intensional approach to statutory meaning can coherently account for change over time. Indeed, we maintain that the dissenters’ only originalist argument that was not beset by anachronism would have rested upon an intensional approach that understood the meaning of sex in light of natural law norms widely shared in 1964.

Our third contribution is a demonstration in Parts II and III of the reality of dynamic interpretation even when jurists are trying to apply an original-public-meaning approach. The no-vehicles-in-the-park hypothetical illustrates our theory of dynamic meaning, but our main objective is to shed light on super-statutes like Title VII. The insights are straightforward, even if judicially unrecognized, and start with an understanding of societal dynamism. If you apply a stable public meaning to ever-evolving social facts, political and economic contexts, and even groups of people, the statute will evolve beyond the original expectations.31 See Farber, supra note 17, at 287–93; infra Part III (arguing that even an original-public-meaning approach to the interpretation of Title VII must recognize that the application of the statute will change over time). In fact, even Justices Alito and Thomas would not apply extensional meaning without some accommodation of new things in the world or old things that change. Their mentor Justice Scalia (cited numerous times in Bostock) certainly did not, nor have Thomas and Alito done so in the context of the Second Amendment’s protection of the right to “keep and bear arms,” which they (like Scalia) apply to modern (fire)arms.32 See infra notes 157–158 and accompanying text. If new weapons are protected under a 1791 constitutional provision, why cannot a new or changed social class be protected under a 1964 statute? What the justices did not appreciate is that in the fifty years after the enactment of Title VII there came to be things in the world (what Alito calls “gays and lesbians”)33Bostock v. Clayton Cnty., 140 S. Ct 1731, 1769 (2020) (Alito, J., dissenting). that, in the eyes of society, did not exist in 1964 or have radically changed. As we shall demonstrate, the justices would have been tipped off if they had looked beyond dictionary definitions or if their intense search into dictionaries of the 1960s had been more thorough.34 Id. at 1784–89 (reporting definitions of sex in the leading dictionaries of the 1960s); see also Hively v. Ivy Tech Cmty. Coll., 853 F.3d 339, 362–63 (7th Cir. 2017) (en banc) (Sykes, J., dissenting) (insisting that sex was limited to biological difference between men and women but citing only three dictionaries cherry-picked to that effect).

A deeper problem besets all three Bostock opinions. As we establish via corpus analysis in Part III, the public meaning of the term sex in 1964 cannot be limited to ‘biological distinctions between male and female.’ Sex had a broader, more catch-all meaning than it usually does today, where terms like gender and sexual orientation (and other terms like sexuality) denote concepts that once could be referred to as sex (on its own and in compounds). Thus, all three Bostock opinions appeared oblivious to linguistic dynamism: none of the opinions acknowledged how pervasively and deeply the regulatory term sex had changed in the last half century. Yet, as we demonstrate, that is precisely what happened. Indeed, the regulatory term evolved both descriptively and normatively: the broad and undifferentiated term sex gave way to the meteoric rise of gender as a way of talking about social roles for men and women that were not driven by biology. This twin evolution of language and norms describes and justifies the arc of EEOC and Supreme Court precedents interpreting Title VII’s sex-discrimination bar to an expanding array of gendered decisionmaking by employers. Indeed, it explains the subtle shifts in rhetoric of Justice Gorsuch’s opinion for the Court: he starts with ‘sexas biology,’ having stipulated to the narrow meaning of sex, but early in the opinion starts writing about ‘sexas gender’ as though they were part of the same concept—which they were, in the 1960s.35 Compare Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1739 (proceeding under the assumption that sex refers “only to biological distinctions between male and female”), with id. at 1741 (describing examples of sex discrimination in which a woman is fired because she is “insufficiently feminine” and a man is fired because he is “insufficiently masculine”). As the dissenters vaguely perceived, Gorsuch was deploying ‘sexas gender’ normatively, reflecting the understanding held by the EEOC and the Court that the project of Title VII was to police employer insistence on traditional gender roles.36 Id. at 1761 (Alito, J., dissenting).

Among our other contributions, we thus hope to demonstrate that even an understanding of statutory interpretation that focuses exclusively on the ordinary meaning of words cannot be viewed as merely the delivery of the public meaning that would have been found at the time of enactment.37Of course, such an understanding is also implausible given our legal culture’s commitment to stare decisis, respect for legislative deliberations, deference to agency views, and substantive canons such as the canon of constitutional avoidance. Original public meaning requires a deep understanding of history that is hard for generalist judges to master and may be an uphill struggle even for historians. As Geoffrey Hawthorn has observed, “even if one manages to play old music on old instruments, one cannot hear it with old ears.”38Geoffrey Hawthorn, Enlightenment and Despair: A History of Social Theory, at ix (2d ed. 1987) (paraphrasing Bernard Williams, Descartes: The Project of Pure Enquiry, at xiii (Routledge 2005) (1978)). We are indebted to Kristin Luker for this reference. The music of old statutes will be heard by interpreters who cannot entirely escape their own social and normative frames.

Within the foregoing limitations, we make a modest suggestion. The rhetoric of original public meaning is an opportunity for judges to explore approaches to statutory text that require them to think about language more systematically and objectively. If the linguistic meaning of a statute is to be privileged, judges should embrace knowledge and insights from linguistics and philosophy of language, rather than dictionary definitions and ad hoc linguistic judgments. Doing so would help judges escape their own linguistic idiosyncrasies and substantive biases and apply text in ways that are more genuinely neutral.39 See Lawrence M. Solan, The Language of Judges 62 (1993) (“[J]udges do not make good linguists because they are using linguistic principles to accomplish an agenda distinct from the principles about which they write.”). In this way, judicial interpretations that conceal evolutive judgments or ideological biases behind poor textual, linguistic, and historical analyses can be brought out of the closet and evaluated for what they are—dynamic through and through, but in ways that fail to comport with how language functions. We add a less modest suggestion for originalist judges: please be aware that you are filtering old language through your own linguistic and normative lenses. Your role as a neutral arbiter requires you to internalize the linguistic and normative lenses that the broader society, and not just your social or political cohort, has come to accept.

I. A Framework for Understanding Original Public Meaning in a Changing Society

It is remarkable that the biggest statutory-interpretation case of the Court’s 2019 Term contained no great debates between textualist and pragmatic justices, as there often were during Justice Scalia’s tenure.40 See, e.g., W. Va. Univ. Hosps., Inc. v. Casey, 499 U.S. 83 (1991). This case is a prototypical example of such Scalia-era debates. Justice Scalia, writing for the Court, interpreted the phrase “a reasonable attorney’s fee” to have a plain meaning that did not allow for the recovery of expert fees, id. at 88, which Justice Stevens rejected as a “literal approach” inconsistent with the “congressional purpose,” id. at 112–13 (Stevens, J., dissenting). But there was a great debate among the three opinions, all of which claimed the mantle of Justice Scalia, textualism, and original public meaning. In varying degrees, the three opinions in Bostock address language issues raised by original-public-meaning theory, such as (1) the interpretive question posed by the public-meaning standard, (2) the linguistic and other context relevant to the interpretation of the statutory phrase at issue, and (3) temporal issues involving how the passage of time affects the meaning of the text. Our main objective is to address the fundamental flaw in all three opinions: their rejection of the proposition that a statute is a dynamic entity and societal, normative, and linguistic evolution might cause its application to change over time. We focus on the third category of issues, but the three categories are interrelated, and our insights also address issues involving the framing of public meaning and the evidence relevant to its determination.

Determining the original public meaning of a text is a notoriously difficult endeavor. Judges have struggled to establish public meaning through historical analysis, consultation of dictionaries, searches of newspaper and academic articles, as well as unsupported assertions about what the public, or some reasonable person, would have believed about the meaning of the text at the time of enactment.41One problem with speculating about how some ‘reasonable person’ (or community) would have understood the meaning of a specific provision at the time of enactment is that there is no way of directly measuring that (hypothetical) understanding and the interpreter may, even if unintentionally, substitute her understanding for that of the reasonable person. See Lawrence Solan, Terri Rosenblatt & Daniel Osherson, Essay, False Consensus Bias in Contract Interpretation, 108 Colum. L. Rev. 1268, 1268–69 (2008) (explaining the concept of “false consensus bias,” which describes the propensity to believe that one’s views about meaning are the predominant views). Today, there are various corpora, or databases of public texts, that can be searched for particular terms and some context. To utilize these databases effectively, the interpreter must channel the linguistic evidence into an organizing conceptual framework that represents valid linguistic choices.42 See Mark C. Suchman, The Power of Words: A Comment on Hamann and Vogel’s Evidence-Based Jurisprudence Meets Legal Linguistics—Unlikely Blends Made in Germany, 2017 BYU L. Rev. 1751, 1758 (2017) (“[T]o transmute a collection of empirical observations into a body of empirical knowledge requires both an organizing conceptual framework and a purposeful investment in synthesis.”). A coherent conceptual framework is crucial because complex temporal aspects of meaning are implicated when the statutory application arises decades after the law was enacted. Bostock illustrates both the undertheorized judicial approach to the temporal aspects of interpretation and the difficulties of applying any interpretive theory to a statute enacted long ago. Every opinion considered the statutory text critically important and insisted that it yielded one unambiguous meaning. Yet the six majority justices endorsed a plain meaning rejected by the three dissenting justices, and none of the opinions offered an adequate theory of language in accomplishing the task of applying that text to a new problem. In fact, because all the justices conceded or acquiesced in the view that Title VII has an unchanging public meaning, no particular legal relevance was given to whether the ‘objects’ of that meaning (‘gays and lesbians’ and ‘transgender persons’) or their constitutional status had changed over time.43 See supra notes 10−11 and accompanying text. As we shall see in Part III, all three opinions in Bostock assumed a static society and constitutional regime.

In this Part, we address crucial theoretical issues surrounding the understanding and application of original public meaning from the perspective of linguistic theory. We start with what is ‘public’ about public meaning, then address the concept of public ‘meaning,’ and finally explain how none of the opinions in Bostock described a persuasive version of the ‘public meaning’ concept.44We save our criticisms of the Court’s opinion until Part III, infra. The discussion is intended to provide an understanding of how temporal issues involving the passage of time affect the meaning of legal texts. The potential for term and object meanings to change over time creates various combinations of language evolution that present distinct issues for legal interpreters. Sometimes this evolution reflects societal dynamism rather than language change, which can nevertheless require changes in how a statute is applied.45We thus distinguish between situations where a court recognizes the changed meaning of some word or phrase in a statute and situations where the court applies the original meaning to some new or changed object or concept. There is debate within the philosophical literature about whether the application of a statute to an object or concept changes the meaning of the statute. See generally Andrei Marmor, Interpretation and Legal Theory (Hart Publ’g rev. 2d ed. 2005) (1992) (discussing the constructive model of interpretation and the semantic natural law theory of interpretation). Certainly, some applications of a statute change the statute’s meaning, such as ones where the court must precisify the statutory language in order to apply the statute. Brian G. Slocum, Ordinary Meaning: A Theory of the Most Fundamental Principle of Legal Interpretation 6 (2015). Nevertheless, we refer in this Article to a narrower notion of ‘meaning’ that is synonymous with the linguistic meaning of a statute’s terms. At other times, linguistic dynamism occurs when the meaning of the statutory language itself has evolved over time.46Of course, both societal and linguistic dynamism might occur simultaneously, as is the case with Title VII. See infra Part III. In Part II, we explore the importance of normative dynamism. See infra Part II. To illustrate how both societal and linguistic dynamism can result in statutory dynamism, we shall consider the following three scenarios:

(1) the meaning of a statutory term is deemed to be fixed at enactment, in accordance with an originalist view of interpretation, but the object of interpretation did not exist at the time of statutory enactment;

(2) the meaning of a statutory term is deemed to be fixed at enactment, in accordance with an originalist view of interpretation, and the object of interpretation did exist at the time of statutory enactment, but its features have significantly changed; and

(3) the meaning of a statutory term has changed over time.

The first two scenarios involve societal dynamism; the third, linguistic dynamism. We discuss the three scenarios in this Part and then illustrate them via the no-vehicles-in-the-park hypothetical in Part II. As we explain below, the third scenario is at odds with most originalist theories, but originalists sometimes accept the first two.

A. Framing the ‘Public’ of Original Public Meaning

Legal interpretation generally seeks to measure the beliefs or actions of some particular class of people. Sweeping broadly, courts sometimes focus on the language production of the legislature and at other times on language comprehension, typically of the ordinary person or interpretive community.47Judge Frank Easterbrook, for example, believes that “the significance of an expression depends on how the interpretive community alive at the time of the text’s adoption understood those words.” Frank H. Easterbrook, Foreword to Antonin Scalia & Bryan A. Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts, at xxv (2012). See also Richard H. Fallon, Jr., The Statutory Interpretation Muddle, 114 Nw. U. L. Rev. 269, 289–96 (2019) (describing how intentionalists and textualists frame the objective of interpretation). Notwithstanding differing interpretive perspectives, most judges today agree that, to some degree at least, language comprehension should be prioritized.48 E.g., Harvard L. Sch., The 2015 Scalia Lecture: A Dialogue with Justice Elena Kagan on the Reading of Statutes, YouTube, at 08:29 (Nov. 25, 2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dpEtszFT0Tg (“We are all textualists now.”). That is, courts presume that language in legal texts should be given its ordinary meaning, determined by general principles of language usage that apply outside the law.49 See Slocum, supra note 45, at 3 (“[C]ourts typically seek to determine the ordinary meaning of legal texts when deciding cases.”); see also District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 576–77 (2008) (“In interpreting this text, we are guided by the principle that ‘[t]he Constitution was written to be understood by the voters; its words and phrases were used in their normal and ordinary as distinguished from technical meaning.’” (quoting United States v. Sprague, 282 U.S. 716, 731 (1931))). The ordinary-meaning standard is justified in part on the basis that it is consistent with fundamental principles of legal interpretation, such as the notions that the public should be able to read and understand legal texts and that the law should be predictable and objective in its application.50See Herman Cappelen, Semantics and Pragmatics: Some Central Issues, in Context-Sensitivity and Semantic Minimalism: New Essays on Semantics and Pragmatics 3, 19 (Gerhard Preyer & Georg Peter eds., 2007) (“When we articulate rules, directives, laws and other action-guiding instructions, we assume that people, variously situated, can grasp that content in the same way.”); see also William N. Eskridge Jr., Interpreting Law: A Primer on How to Read Statutes and the Constitution 33−55 (2016) (making a normative case for the key role played by ordinary meaning). But do judges trained in the doctrines and language of law and drawn from an unrepresentative slice of society have a comparative advantage in figuring out how ordinary people would understand statutory language?

1. The Basic Concept of ‘Ordinary Meaning’

The ordinary-meaning concept typically focuses on how an average reader—the typical member of the public—would understand the relevant language, as opposed to the legislature’s intent or purpose in creating it.51 See Thomas W. Merrill, Essay, Textualism and the Future of the Chevron Doctrine, 72 Wash. U. L.Q. 351, 351–52 (1994) (explaining that textualism seeks objectivity by focusing on “what the ordinary reader of a statute would have understood the words to mean at the time of enactment” as opposed to the legislature’s intent in creating the statute). Certain Supreme Court opinions also focus on the likely interpretation of an ordinary person. See, e.g., Bond v. United States, 572 U.S. 844, 861 (2014) (“When used in the manner here, the chemicals in this case are not of the sort that an ordinary person would associate with instruments of chemical warfare.”). In that sense, it measures the ‘public’ meaning of the text, as all three opinions in Bostock recognized.52 See James A. Macleod, Ordinary Causation: A Study in Experimental Statutory Interpretation, 94 Ind. L.J. 957, 957, 961 (2019) (using “ordinary meaning” and “public meaning” interchangeably). Justice Holmes famously opined that the interpreter’s role is not to ask what the author meant to convey but instead to determine “what those words would mean in the mouth of a normal speaker of English, using them in the circumstances in which they were used.”53Oliver Wendell Holmes, The Theory of Legal Interpretation, 12 Harv. L. Rev. 417, 417–18 (1899). By its very nature, the ‘ordinary’ meaning of a provision must consist of elements that cut across contexts and are external to the interpreter’s preferences.54 See Brian G. Slocum & Jarrod Wong, The Vienna Convention and the Ordinary Meaning of International Law, 46 Yale J. Int’l L. (forthcoming 2021). This may sound pretty simple, but distinguishing between the linguistic meaning of language and subjectively perceived purpose is often difficult; and, in any case, determining that linguistic meaning is typically not the end of the interpretive process.

From a linguistic perspective, considerations of context and purpose are ineliminable aspects of the ordinary meaning determination. With natural-language understanding, and particularly with legal texts, the goal is to determine what a sentence means in a given context of utterance rather than just what it could mean in general.55 See Eskridge, supra note 50, at 3–11 (discussing the importance of statutory purpose and other context to interpretation). Thus, in addition to conventions of language, an ordinary meaning must be informed by contextual and purposive evidence, which is sometimes extratextual in nature. For example, in determining whether a ‘no vehicles’ law prohibits bicycles from the park, the interpreter (like an ordinary person) might consider the perceived purpose of the law: if it is to cleanse the park of noxious fumes and motor noises, bikes would be okay—but probably not if it is to make the park safe for the elderly and small children.56 See Hart, supra note 15, at 607 (indicating that bicycles may or may not be included in a no-vehicles law); see also Eskridge, supra note 50, at 4–5 (explaining that statutory purpose would determine whether to include bicycles); cf., e.g., State v. Barnes, 403 P.3d 72, 73–75 (Wash. 2017) (holding that a riding lawn mower was not a “motor vehicle” within the meaning of a motor-vehicle-theft statute because the statute was enacted to combat the high rate of automobile theft).

Even when it can be ascertained, ordinary meaning often (typically?) underdetermines the actual interpretations made by even its most ardent judicial adherents.57 See Ludlow, supra note 19, at 65 (“The words used by lawmakers are just as open-ended as words used in day-to-day conversation.”). The extent to which ordinary meaning underdetermines a court’s interpretation depends, obviously, on how broadly ‘ordinary meaning’ is defined. While a very narrow definition of ordinary meaning may be unsatisfactory because it underdetermines interpretations in every case, an unduly broad definition will lead to incoherence because it serves merely as a conclusory label for whatever interpretation a court finds to be most persuasive. Often, precise binary distinctions are required to resolve interpretive disputes, which the ordinary meaning of language typically does not provide, forcing judges to look elsewhere for interpretive resolution.58 See Brian G. Slocum, Replacing the Flawed Chevron Standard, 60 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 195, 238−39 (2018) (explaining how legal interpretation’s reliance on bivalency, “the idea that interpretative questions have ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers,” is in tension with the prototypical structure of language). Furthermore, it might be clear that the relevant textual language should be given a special legal or technical meaning, or even some meaning that is not technical or legal but is seldom used (and thus an unordinary meaning).59Thus, ordinary meaning is defeasible. See, e.g., Taniguchi v. Kan Pac. Saipan, Ltd., 566 U.S. 560, 569 (2012) (“[T]he word ‘interpreter’ can encompass persons who translate documents, but because that is not the ordinary meaning of the word, it does not control unless the context in which the word appears indicates that it does.”). For instance, Justice Alito argued in his Bostock dissent that “discriminate because of sex” was a term of art used in previous statutes and orders, which had an accepted legal meaning in 1964.60Bostock v. Clayton Cnty., 140 S. Ct. 1731, 1764−76 (2020) (Alito, J., dissenting). In addition, a judge’s understanding of ordinary meaning will be influenced or even controlled by prior decisions; you cannot have a theory of statutory interpretation or legal meaning without having a theory of precedent.61 See Eskridge, supra note 50, at 139−90; Michael J. Gerhardt, The Power of Precedent 97 (2008); David A. Strauss, Common Law Constitutional Interpretation, 63 U. Chi. L. Rev. 877 (1996). All the Bostock opinions made some effort to justify their interpretations of Title VII as consistent with precedent, and the Gorsuch opinion secured most of its persuasive power by invoking the Court’s interpretation of Title VII to reach sexual harassment of working women, coworkers’ homosexual harassment, and gender stereotyping.62 Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 17443 (“All that the statute’s plain terms suggest, this Court’s cases have already confirmed.”). Finally, the commonsense, person-on-the-street meaning of the textual language may be legally unacceptable for some reason, such as a meaning that would raise a serious constitutional issue or result in absurdity.63The absurdity doctrine may be the clearest example of a situation where a court has rejected the meaning of the text (whether communicative or otherwise) in favor of some other meaning. See John F. Manning, The Absurdity Doctrine, 116 Harv. L. Rev. 2387, 2389 (2003). The avoidance canon is another example where the interpretation chosen by the court might not conform to the intended meaning of the statute or the meaning an ordinary reader would give it. See Eric S. Fish, Constitutional Avoidance as Interpretation and as Remedy, 114 Mich. L. Rev. 1275, 1275 (2016). In such cases, a court’s interpretation will be based on principles that reflect normative legal commitments but that arguably reflect neither language production nor comprehension.64 See Fish, supra note 63.

2. Public Meaning as an Empirical Question or a Linguistic Question

The justices in Bostock might have all agreed on the proper objective of interpretation, ‘original public meaning,’ but how is the language comprehension of the public to be measured? Not a single justice in Bostock offered direct evidence of whether the average American would have read in 1964, or would read today, the language of Title VII to protect gay, lesbian, or transgender employees.65 Cf. Macleod, supra note 52 (analyzing how an ordinary reader would understand Title VII’s language by asking ordinary readers to apply that language in context, drawing on a set of nationally representative survey experiments); Shlomo Klapper, Soren Schmidt & Tor Tarantola, Ordinary Meaning from Ordinary People, U.C. Irvine L. Rev. (forthcoming 2021) (using surveys to measure how ordinary people apply statutes to specific interpretive disputes). In fact, the opinions largely ended up talking past each other because the majority’s conception of public meaning differed from that of the dissenting opinions. In turn, this divergence led to conflict regarding which interpretive sources help determine public meaning.66 See Slocum, supra note 45, at 36−37 (describing the constituent and evidential questions of statutory interpretation).

The reasoning of the Court’s opinion focused on compositional public meaning. The principle of compositionality states that “the meaning of a complex linguistic expression is built up from the meanings of its composite parts in a rule-governed fashion.”67M. Lynne Murphy & Anu Koskela, Key Terms in Semantics 36 (2010). A sentence is compositional if its meaning is the sum of the meanings of its parts and of the relations of the parts.68 See id. Describing “compositionality” in a general sense is sufficient for our purposes, although different versions of the concept are stronger or weaker and can take more or less context into account. See Zoltán Gendler Szabó & Richmond H. Thomason, Philosophy of Language 58 (2019) (describing various forms of compositionality, including “weak compositionality (with context)”). Thus, the Court’s opinion did not focus on perceived public views about the meaning of Title VII, or gay men, lesbians, and transgender persons. Rather, the Court addressed the individual meanings of Title VII’s terms, “discrimination,” “because of,” and “sex,” maintaining that the overall meaning of the provision would be the sum of its composite parts.69Bostock v. Clayton Cnty., 140 S. Ct. 1731, 1744 (2020).

Justice Kavanaugh responded, in dissent, that the Court was focusing on “literal meaning rather than ordinary meaning.”70 Id. at 1824 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting). He introduced phrases such as “American flag,” “cold war,” and “washing machine,” which have conventional (and thus ordinary) meanings that cannot easily be determined from combining the meanings of the individual words (and thus are not compositional based on the sum of the composite parts).71 Id. at 1826. Justice Kavanaugh is correct that courts should interpret words in light of the overall meaning of a sentence rather than acontextually.72 See Slocum, supra note 45, at 106–08 (arguing that the ordinary meaning determination should focus on sentence meaning rather than the meaning of individual words). But Justice Kavanaugh must also establish that Title VII’s phrase, “discriminate against any individual . . . because of such individual’s . . . sex,” has some conventional meaning that differs from the compositional public meaning explicated by Justice Gorsuch.7342 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)(1). The Court responded to Justice Kavanaugh’s arguments by pointing out that “the competing dissents [do not] offer an alternative account about what these terms mean either when viewed individually or in the aggregate.” Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1750. Note that this conventional, public meaning would have to be based on language usage outside of the Title VII context at the time of statutory enactment in 1964 (to be conventional and consistent with originalism),74Otherwise, Justice Kavanaugh would be making arguments about the specific meaning of Title VII (based on congressional intent or public understanding) rather than an argument about conventional meaning and the literal meaning versus ordinary meaning debate. as opposed to a meaning that developed after statutory enactment or that was based on the specific context of Title VII.75As a matter of linguistics, Justice Kavanaugh’s arguments about compound words are correct. Christiane Fellbaum explains that phrases, such as “fire sale,” that “are not straightforwardly (de)composed . . . . constitute lexical units despite their multi-word make-up.” Christiane Fellbaum, The Treatment of Multi-word Units in Lexicography, in The Oxford Handbook of Lexicography 411, 411 (Philip Durkin ed., 2015). Thus, the phrases used by Justice Kavanaugh, such as “cold war,” may be understood as single linguistic units rather than separate words whose meanings combine in a predictable way. For his examples to be useful, however, there must be some demonstration that the language in Title VII somehow operates as a single “lexical unit” with an identifiable conventional meaning. Of course, this understanding would have had to be present in 1964 and based on evidence outside of Title VII. Without such a showing, his linguistic arguments about literal meaning versus ordinary meaning, even if correct, would not refute the Court’s reasoning (which was flawed for other reasons).

In contrast to the majority opinion, the two dissenting opinions viewed the public meaning question as involving what could be termed empirical public meaning.76Other than his arguments about literal meaning versus ordinary meaning, Justice Kavanaugh’s evidence was largely relevant to his framing of the ultimate interpretive question of how ordinary people at the time of enactment would have construed Title VII’s terms, not to establishing the conventional meaning of Title VII’s terms as of 1964. Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1828 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting). Both dissenting opinions agreed that the answer to the following question should decide the case: How would the terms of a statute have been understood and applied by ordinary people at the time of enactment?77 Id. at 1767 (Alito, J., dissenting) (“[I]t is imperative to consider how Americans in 1964 would have understood Title VII’s prohibition of discrimination because of sex.”); id. at 1828 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting) (“[C]ourts heed how ‘most people’ ‘would have understood’ the text of a statute when enacted.” (quoting New Prime Inc. v. Oliveira, 139 S. Ct. 532, 539 (2019))). Unlike the case with compositional public meaning, where any empirical inquiry is focused on conventional meanings at the word or phrasal level, empirical public meaning purports to focus the inquiry on the actual views that the American public would have had about the ultimate interpretive question in 1964. It assumes that Congress must have enacted exactly what the public thought it enacted. If taken seriously, however, the question posed may lead to results that would surprise the dissenting justices. Justice Alito’s dissenting opinion accused the Court’s opinion of being like a “pirate ship” because it falsely “sails under a textualist flag,”78 Id. at 1755 (Alito, J., dissenting). but the interpretive question posed by the dissenting opinions is not necessarily textualist. The dissenting justices pose in essence an empirical question about ‘ordinary people,’ but existing empirical evidence (consistent with linguistic theory) suggests that ordinary people use normative and purposive reasoning when interpreting statutory provisions.79Klapper et al., supra note 65.

In fact, actual surveys of ordinary people demonstrate a much broader public understanding of Title VII’s terms than the dissenting justices acknowledge.80 Compare Macleod, supra note 52, at 999–1001 (finding that ordinary readers interpret Title VII to cover instances when sex discrimination is not the but-for cause of the firing), with Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1755 (Alito, J., dissenting), and id. at 1828 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting) (asserting that ordinary people in 1964 would not have interpreted Title VII to ban firing an employee because of sexual orientation). While the dissenting justices might object that these surveys are recent, rather than from 1964, we argue in Part III that societal dynamism, which should be accepted by originalists, has caused the meaning of Title VII to change over time. See infra Part III. Indeed, much of the evidence offered by the dissenting opinions was more purposive than textualist in nature, including arguments about the “social context” in which Title VII was enacted81 Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1767 (Alito, J., dissenting) (explaining that the social context “may have an important bearing on what [a statute’s] words were understood to mean at the time of enactment” because “[s]tatutes consist of communications between members of a particular linguistic community, one that existed in a particular place and at a particular time, and these communications must therefore be interpreted as they were understood by that community at that time”). and “the societal norms of the day,”82 Id. at 1769. as well as “congressional practice,”83 Id. at 1829 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting). which instructed the dissenters that in 1964 discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or transgender status “would not have been evil at all.”84 Id. at 1774 (Alito, J., dissenting). The dissenting opinions also relied on dictionary definitions (Justice Alito compiled an appendix of more than a dozen contemporary dictionary definitions of sex), but dictionary definitions provide the sort of acontextual word meanings that Justice Kavanaugh condemned and, in any case, provide at best very indirect and conflicting evidence regarding how ordinary people would have understood and applied Title VII in 1964.85As we shall demonstrate in Part III, Justice Alito, who staked most of his opinion on dictionaries, used them selectively and then failed to understand the entries that he reported—indeed, he failed to understand the best ‘originalist’ argument suggested by the dictionaries. See infra Part III.

We do not aim to offer a comprehensive account of the ‘public’ in ‘public meaning,’ but we note some problems with empirical public meaning as it is applied by the dissenting opinions. Perhaps most importantly, even if it is accepted as a legitimate way to frame public meaning, original empirical public meaning underdetermines any legal interpretation. By definition, determining in 2021 how an ordinary person would have understood and applied a statute in 1964 ignores intervening judicial and agency interpretations and, as we argue later, important legal, societal and linguistic evolution.86 See infra Part III. Furthermore, the standard undervalues the extent to which legal training and knowledge are integral to statutory interpretation. Statutory interpretation is typically a multilayered process that involves normative decisions, specialized legal competence, and inferences from context. For instance, judges are generally more competent at evaluating and understanding legislative history or inferences from related provisions than ordinary people.87It would likely be a legal fiction to assume that ordinary people would consult legislative history when interpreting a statute. The empirical-public-meaning approach does raise important questions about empiricism and statutory interpretation, but it poses a question that cannot be answered directly (How would the terms of a statute have been understood and applied by ordinary people at the time of enactment?), as though a straightforward answer is possible and should constitute the court’s interpretation.88 Cf. Gregory C. Keating, Reasonableness and Rationality in Negligence Theory, 48 Stan. L. Rev. 311, 339 (1996) (arguing that the “average” in the average-reasonable-person doctrine “is a normative one, established by an objective community standard that may or may not be representative of actual human actors”).

3. Corpus Linguistics as a Tool that Offers Evidence of Public Meaning

Regardless of whether a compositional or an empirical approach to public meaning is chosen, judges typically gather information external to themselves about word meanings. As lavishly illustrated in Bostock,89 Bostock, 140 S. Ct. at 1740 (majority opinion); id. at 1756−58, 1784−91 (Alito, J., dissenting). judges frequently consult dictionary definitions, although such use has been devastatingly criticized by scholars.90 See, e.g., James J. Brudney & Lawrence Baum, Oasis or Mirage: The Supreme Court’s Thirst for Dictionaries in the Rehnquist and Roberts Eras, 55 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 483 (2013) (citing and expanding upon prior critiques). The criticisms tend to focus on how dictionaries are misused by courts, such as the arbitrary selection of a definition within one of many dictionaries.91Ellen P. Aprill, The Law of the Word: Dictionary Shopping in the Supreme Court, 30 Ariz. St. L.J. 275, 297–300 (1998) (stating that the level of linguistic analysis performed by courts rarely rises above “dictionary shopping”). A more fundamental criticism is that judicial reliance on dictionaries in general is problematic.92Brudney & Baum, supra note 90. A dictionary definition provides a general description of the concept involved but is often prescriptive rather than descriptive and does not always aim to provide a necessary and sufficient set of features for membership in the category at issue.93 See Slocum & Wong, supra note 54, at 3; Kevin P. Tobia, Testing Ordinary Meaning, 134 Harv. L. Rev. 726 (2020) (illustrating through empirical evidence that dictionaries give broad definitions that may not correspond with the ordinary meanings of words); see also Nick Riemer, Word Meanings, in The Oxford Handbook of the Word 305, 315 (John R. Taylor ed., 2015) (“A striking feature of dictionary definitions is their variability.”). In fact, “the dictionary takes words away from their common use in their customary settings,” which “can be highly misleading if used as a basis of theorizing about what words and their meanings are.”94M.A.K. Halliday & Colin Yallop, Lexicology: A Short Introduction 24–25 (2007). Considering dictionaries’ limitations, alternative sources of information about the public meaning of words such as corpus linguistics will inevitably receive increasing attention.

Corpus analysis may be a useful source of information about communications that occur outside of the law, and the sort of information produced via corpus linguistics is relevant to public meaning.95 See Stefan Th. Gries & Brian G. Slocum, Ordinary Meaning and Corpus Linguistics, 2017 BYU L. Rev. 1417, 1422–33 (2017). Corpus searches can illustrate such things as “the number of senses (i.e., meanings) a linguistic expression may have” and the most frequently used meaning (in general or per context).96 Id. at 1441. Corpus searches can also provide information about “the most prototypical meaning of an expression.”97 Id. Importantly, in providing information about public meaning, corpus analysis can account for context in ways that dictionary definitions cannot. For instance, “[u]nlike dictionaries, corpus linguistics allows for the meanings of words to be investigated” in terms of other words in which they co-occur in natural and authentic contexts of ordinary language use.98 Id.

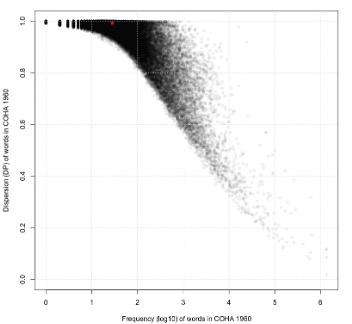

One of the leading historical databases for American English is the one we use in this Article—the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA), which contains more than 400 million words of text from the 1810s to the 2000s (making it 50–100 times as large as other comparable historical corpora of English).99 See Corpus Hist. Am. Eng., https://www.english-corpora.org/coha [https://perma.cc/CJ6L-DSBV?type=image]. COHA is balanced by genre and by decade. Thus, a contemporary judge interpreting a 1964 law barring “vehicles” from the park can focus her search on sources from the 1950s and 1960s or can look more broadly (to include the 1940s and 1970s perhaps). She could even engage in a search of thousands of public documents from the 1850s and 1860s if she were applying an 1864 no-vehicles-in-the-park regulation to an object found in the park this year. For the researcher, COHA is therefore particularly useful because it allows comparisons of word usage across decades.

For very old legal documents, like the Constitution of 1789, originalists have been hampered by the antiquity of the text, which they have tried to translate to solve modern issues—usually to be embarrassed by evidence from legal historians that they have fallen prey to gross anachronism, source cherry-picking, and result-oriented research and reasoning.100 See Jonathan Gienapp, Historicism and Holism: Failures of Originalist Translation, 84 Fordham L. Rev. 935 (2015); Jack N. Rakove, Joe the Ploughman Reads the Constitution, or, The Poverty of Public Meaning Originalism, 48 San Diego L. Rev. 575 (2011); William Michael Treanor, Taking Text Too Seriously: Modern Textualism, Original Meaning, and the Case of Amar’s Bill of Rights, 106 Mich. L. Rev. 487 (2007). Their efforts to apply original-public-meaning methodologies to old statutes have been even less successful.101For example, the textualist assault on Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 143 U.S. 457 (1892), by Justice Scalia and his allies, see Antonin Scalia, A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law 18–23 (Amy Gutmann ed., new ed. 2018), has been met with strong and persistent criticism. See Carol Chomsky, Unlocking the Mysteries of Holy Trinity: Spirit, Letter, and History in Statutory Interpretation, 100 Colum. L. Rev. 901 (2000); William N. Eskridge, Jr., Textualism, the Unknown Ideal?, 96 Mich. L. Rev. 1509 (1998) (reviewing Scalia, supra). A central problem has been that the founding generation spoke a different language than what we speak today, and the task of understanding or translation is conceptually as well as linguistically complicated. As we shall see in Part III, even justices who came of age in the 1960s made elementary mistakes in understanding that decade (and their reliance on contemporary dictionaries did nothing to ameliorate their anachronisms). Historical corpus research, conducted via scientifically valid principles, might therefore be a mechanism for judges to approach some questions of public meaning more objectively and neutrally—or at least to check their intuitions against outside evidence.102For an example of excellent corpus linguistic research applied to a legal problem, see Tammy Gales & Lawrence M. Solan, Revisiting a Classic Problem in Statutory Interpretation: Is a Minister a Laborer?, 36 Ga. St. L. Rev. 491 (2020) (providing corpus research bearing on the iconic Holy Trinity case, discussed in the previous note).

B. Framing the ‘Meaning’ of Original Public Meaning

Understanding the flawed approaches to public meaning in Bostock, as well as how the interpretation of super-statutes like Title VII should be conducted, also requires a framework for the ‘meaning’ part of original public meaning. Here especially, insights and knowledge from linguistics and the philosophy of language can improve the theory and practice of legal interpretation. Original public meaning is, after all, framed by its advocates as a linguistic concept rather than a normative one dependent on judicial ideology.103 See Lawrence B. Solum, Triangulating Public Meaning: Corpus Linguistics, Immersion, and the Constitutional Record, 2017 BYU L. Rev. 1621, 1626 (2017) (describing “[p]ublic meaning originalism” and its connection to the linguistic meaning of the legal text). As a linguistic concept, the public meaning of a text raises issues of categorization, which have been of particular interest to linguists.104 See Joan Bybee, Language Change 196 (2015) (“[W]ords designate categories. For this reason, research on categories in both psychology and linguistics is relevant to the study of word meaning.”). In fact, virtually every issue of legal interpretation involves categorization: whether a certain intangible concept or concrete object falls within the boundaries of the category created by the regulatory provision.105In addition to being essential to the operation of the law, categorization is an integral aspect of human development. See Vladimir M. Sloutsky, The Role of Similarity in the Development of Categorization, 7 Trends Cognitive Scis. 246 (2003); see also Zeki Hamawand, Semantics: A Cognitive Account of Linguistic Meaning 135 (2015) (“Categories mirror human sensory modalities . . . . [T]he conceptual system is organized in terms of categories, which relate to entities experienced in the world.”). The process of categorization requires an ability to cognitively accommodate both similarities and differences.106In general, categorization is beneficial because it allows for the organization of knowledge through the creation of taxonomies that include smaller classes within larger ones (e.g., Specific Creature → Yorkipoo → Dogs → Animals). It is part of inductive generalization, where, for example, knowing that a creature has (many) features similar to recognized members of the category ‘dogs,’ and few relevant features shared by non-dogs, enables one to categorize the creature as a dog.107In fact, early in their development humans demonstrate the ability to countenance differences in order to generalize and form categories based on similarities. Sloutsky, supra note 105, at 246–47.

1. Extensional Versus Intensional Meaning

In making categorization decisions, judges act in part as quasi lexicographers.108Judges are quasi lexicographers at least for the purposes of resolving an interpretive dispute and justifying that decision in a written opinion. So lexicographical standards and principles might be useful for judges, although many of the choices faced by lexicographers are fairly straightforward for judges.109 See generally Dirk Geeraerts, Meaning and Definition, in A Practical Guide to Lexicography 83 (Piet van Sterkenburg ed., 2003) (describing some of the choices faced by lexicographers). For instance, one typical choice for the legal interpreter is to focus on determining referential, descriptive meaning (“denotational meaning”), as opposed to something like “emotive meaning” (describing the emotional overtone of the word, e.g., pejorative). See id. at 86–87. One crucial, but nonobvious and currently unrecognized, distinction relevant to legal interpretation is between intensional and extensional ways of analyzing meaning.110The distinction is similar to the sense/reference distinction made famous by Gottlob Frege. See Gottlob Frege, Über Sinn und Bedeutung [On Sense and Reference], 100 Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik 25 (1892), translated in The Frege Reader 151 (Michael Beaney ed., 1997). The sense/reference distinction has been proposed as a theory of originalism in constitutional law. See, e.g., Christopher R. Green, Originalism and the Sense–Reference Distinction, 50 St. Louis U. L.J. 555, 564 (2006). The ‘extensional’ meaning of a term is the collection of things that fall within the scope of the term.111 See Luca Gasparri & Diego Marconi, Word Meaning, Stan. Encyc. Phil. (Mar. 21, 2021), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2021/entries/word-meaning [https://perma.cc/ETH8-D292]. Complex expressions also have extensions. David Braun, Extension, Intension, Character, and Beyond, in The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Language 9 (Gillian Russell & Delia Graff Fara eds., 2012). Thus, the extensional meaning of planet consists of the objects to which the term may be correctly applied (the set of Mercury, Venus, and so on).112 See Gasparri & Marconi, supra note 111. In contrast, the ‘intensional’ meaning of planet consists of the set of attributes shared by all and only those objects to which the term refers, namely, celestial bodies of a certain size and gravity that orbit a star.113 See id.; see also Bybee, supra note 104, at 196 (describing intension as “a statement of the defining features of the category the word designates”). For instance, consider NASA’s definition of a planet:

(1) It must orbit a star (in our cosmic neighborhood, the Sun).

(2) It must be big enough to have enough gravity to force it into a spherical shape.

(3) It must be big enough that its gravity cleared away any other objects of a similar size near its orbit around the Sun.

What Is a Planet?, Nat’l Aeronautics & Space Admin., https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/in-depth [https://perma.cc/8BS3-763N]. Terms have both an extensional and intensional meaning, where the intension determines the extension but not vice versa.114Francesco Orilia, Meaning and Circular Definitions, 29 J. Phil. Logic, 155, 163 (2000). Most terms, being noneternal, have different extensions at different times.115 See Wayne A. Davis, On Nonindexical Contextualism, 163 Phil. Stud. 561, 562 (2013). For example, in 1920 the extension of airplane did not include any jets, but its extension in 2021 does.116 See id. In contrast, even though its extension will change constantly over short periods of time, the intensional meaning of airplane might, theoretically, remain stable for long stretches of time.117 See id. This would obviously depend on the lexicographical approach taken by the interpreter. Thus, two expressions with the same intension have the same extension, but two expressions with the same extension may have different intensions.118 See Braun, supra note 111, at 10. For example, the term renate has the same extension as the term cordate, but the intension of renate is ‘animal with a kidney’ whereas the intension of cordate is ‘animal with a heart.’119 See id.

In a legal context, it may seem intuitive that meaning should be framed in terms of intension, which is consistent with the typical judicial process of determining the intensional meaning (by reference to a statutory definition, a precedent, or a dictionary) of the term at issue before applying that meaning to the facts of the case.120Some would argue that extensions are not plausible candidates for the meanings of expressions because expressions that have the same extension (coextensive expressions) can differ in meaning. Id. at 10. See Geeraerts, supra note 109, at 89 (explaining that intensional meanings are the ones generally used in dictionaries). Although fraught with difficulties, it is not uncommon to approach interpretive disputes by determining only the extension of an expression, and using corpus linguistics may facilitate this process.121An interpretive dispute is resolved once it is determined whether the statutory term includes within its scope the object or concept in question; determining the extension of the statutory term necessarily resolves that dispute. For example, Justice Thomas Lee and Stephen Mouritsen used corpus analysis to consider whether airplanes and bicycles are ‘vehicles’ regulated by a Hartian no-vehicles-in-the-park statute.122 See Lee & Mouritsen, supra note 25, at 836, 859. Their paper examined collocation, which reveals “the words that are statistically most likely to appear in the same context as vehicle for a given period,”123 Id. at 837. and concordance data, which “allows [] users to review a particular word or phrase in hundreds of contexts, all on the same page of running text.”124 Id. at 832. From this information, the authors concluded that airplanes and bicycles “are attested in the data as possible examples of vehicle” but are “unusual—not the most frequent and not even common.”125 Id. at 859.

Lee and Mouritsen thus did not offer an intensional definition of vehicle based on their corpus research but, instead, focused on the frequency with which the word airplane occurs around vehicle.126 Id. at 837–38. Thus, the focus was on whether “[some noun] is a vehicle.” Gries & Slocum, supra note 95, at 1466. Note, though, that this inquiry does not necessarily include investigation into whether a particular corpus file included an assertion that, for example, an airplane is a vehicle but merely collects data about whether the two terms appear together. With an extensional approach to meaning, the interpreter must sort through the collocation, concordance, and other data and make a determination about whether the producers of the texts being searched demonstrated a belief (even if indirectly) that some concept falls within the scope of the category at issue. This determination will thus be based on the “evaluation of some kind of frequencies.”127Stefan Th. Gries, What Is Corpus Linguistics?, 3 Language & Linguistics Compass 1225, 1226 (2009). There must therefore be some standard above which the frequency of instances can be said to represent category membership. If, for example, airplanes are not mentioned in the same contexts as “vehicles,” the interpreter might conclude that airplanes likely do not fall under the ‘vehicle’ concept.128 See Lee & Mouritsen, supra note 25, at 859. But frequencies of co-occurrence alone are an insufficient basis on which to determine category membership.129Stefan Th. Gries, Corpus Linguistics and the Law: Extending the Field from a Statistical Perspective, 86 Brooklyn L. Rev. (forthcoming 2022) (manuscript at 19) (on file with the Michigan Law Review). Furthermore, with a corpus analysis focused on extensional meaning, the researcher will seek information regarding whether an object such as an airplane or a bicycle is referred to as a vehicle or occurs in the vicinity of vehicle in a text, but such research will not likely capture all the objects that might be considered vehicles.130Likely, there are too many objects to research and, in any case, advances in technology will create new objects to evaluate. Additional research would be required to determine whether any of these other objects (perhaps some new skateboard-like mechanism) is a vehicle.131The Segway is a two-wheeled, self-balancing personal transporter brought to market in 2001 that has an electric motor and a maximum speed of 12.5 miles per hour. Matt McFarland, Segway Was Supposed to Change the World. Two Decades Later, It Just Might, CNN Bus. (Oct. 30, 2018, 1:04 PM) https://www.cnn.com/2018/10/30/tech/segway-history/index.html [https://perma.cc/KY32-C4MG].