On Time, (In)equality, and Death

In recent years, American institutions have inadvertently encountered the bodies of former slaves with increasing frequency. Pledges of respect are common features of these discoveries, accompanied by cultural debates about what “respect” means. Often embedded in these debates is an intuition that there is something special about respecting the dead bodies, burial sites, and images of victims of mass, systemic horrors. This Article employs legal doctrine, philosophical insights, and American history to both interrogate and anchor this intuition.

Law can inform these debates because we regularly turn to legal settings to resolve disputes about the dead. Yet the passage of time, systemic dehumanization, and changing egalitarian norms all complicate efforts to apply traditional legal considerations to disputes about victims of subordination. While, for example, courts usually consult decedents’ expressed intentions to resolve disputes, how do we divine the wishes of people who died centuries ago, under a legal system designed to negate and dishonor their intentions? How do we honor relationships like kinship for people who were routinely and forcibly separated from their kin? And how do we assess the motives or culpability of institutions that, in prior generations, were complicit in profound horrors, but now pledge honor and respect?

This Article offers a theory of time and equality to help guide cultural and legal debates about the treatment of dead victims of mass horror. On this account, we can become complicit in past, systemic subordination by dishonoring the memories of victims. Systemic neglect and exploitation of a group’s bodies and images can diminish the role of that group in shaping our national memory. And if it is wrong to deny a person the ability to leave a legacy on account of race under contemporary egalitarian norms, then we ought not engage in posthumous acts against the enslaved and other systemically debased persons that perpetually rob them of such a legacy.

Introduction

There is no place you or I can go, to think about or not think about, to summon the presences of, or recollect the absences of slaves . . . . There is no suitable memorial or plaque or wreath or wall or park or skyscraper lobby. There’s no 300-foot tower. There’s no small bench by the road.

—Toni Morrison1Toni Morrison, A Bench by the Road, WORLD, Jan./Feb. 1989, at 4, 4 [perma.cc/EKP5-U8DS].

They were mistreated as slaves, and now they are mistreated in death.

—Fred O. Smith, Sr.2Sophia Choi, Pipe Found Near Possible Slave Remains at UGA, WSB-TV (Mar. 28, 2017, 7:25 PM), https://www.wsbtv.com/news/local/pipe-found-near-possible-slave-remains-at-uga/506876978 [perma.cc/D4TN-AMFD].

For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and for the living. He has no right to deprive future generations of a past that belongs to our collective memory. To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.

—Elie Wiesel3ELIE WIESEL, NIGHT, at xv (Marion Wiesel trans., Hill & Wang 2006) (1958).

Physical manifestations of horrors perpetrated long ago stalk the present.4Cf. Letter from James Madison to Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette (Nov. 25, 1820), in 2 The Papers of James Madison, Retirement Series: 1 February 1820–26 February 1823, at 158, 159 (David B. Mattern, J.C.A. Stagg, Mary Parke Johnson & Anne Mandeville Colony eds., 2013) (referring to slavery as America’s “original sin”); Maggie Blackhawk, Federal Indian Law as Paradigm Within Public Law, 132 Harv. L. Rev. 1787, 1800 (2019) (“[L]ike America’s other original sin, traces of America’s history with colonialism are woven in like threads to the fabric of the document.”). During the Trump Administration, fierce debates raged in Arizona and Texas about the federal government’s plans to destroy burial sites of Native Americans and enslaved persons.5See, e.g., Laurel Morales, Border Wall Would Cut Across Land Sacred to Native Tribe, NPR (Feb. 23, 2017, 4:35 AM), https://www.npr.org/2017/02/23/516477313/border-wall-would-cut-across-land-sacred-to-native-tribe [perma.cc/Z47F-ZGRX]; Melissa del Bosque, Trump’s Border Wall Would Destroy Historic Gravesites in South Texas, Intercept (Jan. 21, 2019, 9:00 AM), https://theintercept.com/2019/01/21/border-wall-gravesites-cemetery-texas [perma.cc/5NKF-D9SY]; Native Burial Sites Blown Up for US Border Wall, BBC (Feb. 10, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-51449739 [perma.cc/5WSW-8KB6]. The events prompted multiple lawsuits. E.g., La Posta Band of Diegueño Mission Indians v. Trump, No. 20-cv-01552, 2020 WL 7398763, at *1–2 (S.D. Cal. Dec. 16, 2020); Ctr. for Biological Diversity v. Trump, 453 F. Supp. 3d 11, 28 (D.D.C. 2020). Another recent lawsuit alleges that the executive order creating the border wall violates the Equal Protection Clause. Plaintiffs’ First Amended Original Complaint at 57–59, Zapata Cnty. v. Trump, No. 20-cv-106 (S.D. Tex. Oct. 5, 2020). Moreover, enslaved persons’ bodies have frequently been encountered across the United States in recent decades.6See, e.g., David W. Dunlap, Dig Unearths Early Black Burial Ground, N.Y. Times (Oct. 9, 1991), https://www.nytimes.com/1991/10/09/nyregion/dig-unearths-early-black-burial-ground.html [perma.cc/MCD5-425D]; Amy Quinton, Black Burial Site Paved Over in Portsmouth, N.H., NPR (Feb. 22, 2006, 11:17 AM), https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5228067 [perma.cc/8DTN-P4QL]; Mai-Linh K. Hong, “Get Your Asphalt Off My Ancestors!”: Reclaiming Richmond’s African Burial Ground, 13 Law Culture & Humans. 81, 83 (2017); Robert Hull, University Cemetery Survey Yields More Grave Shafts; Commemoration Panel Formed, UVA Today (Dec. 3, 2012), https://news.virginia.edu/content/university-cemetery-survey-yields-more-grave-shafts-commemoration-panel-formed [perma.cc/KF7R-9EJA]; Kevin McGill, As Shell Preserves Louisiana Slave Burial Ground, Question Persists: Where Are the Rest?, Advocate (June 14, 2018, 9:01 AM), https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/article_5a1ab0fa-6fdb-11e8-b6d6-932aad7138e2.html [perma.cc/QCF6-5VUX]; Megan Mittelhammer, Everything You Need to Know About the Baldwin Hall Controversy, Red & Black (May 4, 2021), https://www.redandblack.com/news/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-baldwin-hall-controversy/article_fff28aa0-bf0a-11e9-9256-4f177f5f318c.html [perma.cc/GQ87-M6VY]; Alice Goulding, U. Will Enlist Expert to Investigate African American Burial Ground Found Under Penn Property, Daily Pennsylvanian (Apr. 18, 2018, 10:32 PM), https://www.thedp.com/article/2018/04/african-american-burial-ground-west-philadelphia-upenn-penn-expert-university-philadelphia [perma.cc/4WYZ-HNV2]; Michaela Winberg, Philly’s Black Burial Grounds and the Battle for Preservation, Billy Penn (Mar. 24, 2019, 9:15 AM), https://billypenn.com/2019/03/24/phillys-black-burial-grounds-and-the-battle-for-preservation [perma.cc/QD4H-QAE6]; Emma Claybrook, Burial Ground for Dozens of Slaves Discovered at AR Church, Phila. Trib. (Nov. 18, 2019), https://www.phillytrib.com/news/across_america/burial-ground-for-dozens-of-slaves-discovered-at-ar-church/article_b774f27e-7082-55e0-8adc-3d873c611dd8.html [perma.cc/JG86-JGQF]; Melissa Lemieux, Florida Country Club Discovered 40 Slave Graves Buried Under Its Property, So What Happens Now?, Newsweek (Dec. 26, 2019, 10:44 PM), https://www.newsweek.com/florida-country-club-discovered-40-slave-graves-buried-under-its-property-so-what-happens-now-1479305 [perma.cc/W7XY-46DB]; Possible Slave Cemetery Found on Georgia College Campus, AL.com (May 13, 2019, 11:55 AM), https://www.al.com/news/2019/05/possible-slave-cemetery-found-on-georgia-college-campus.html [perma.cc/3AQ6-YJCG]. These bodies sometimes hide in plain sight, as with the skulls of Cuban slaves that were on display at the University of Pennsylvania until 2020.7Nora McGreevy, The Penn Museum Moves Collection of Enslaved People’s Skulls into Storage, Smithsonian (Aug. 4, 2020), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/after-outcry-penn-museum-removes-skulls-enslaved-people-public-view-180975466 [perma.cc/RU5A-73E9]. More often, they are disturbed inadvertently.8See, e.g., Dunlap, supra note 6. Pledges of respect are common features of these discoveries, accompanied by cultural debates about what respect means.9When the University of Virginia discovered remains of slaves, it committed to “assure respect for the remains of those buried,” and “to memorialize these graves in as respectful manner as possible.” Hull, supra note 6. This was also the approach when, in 1991, a slave burial site was discovered during the construction of a courthouse in New York City. A government official pledged that it was “absolutely essential that the remains that were found on the site be treated with the utmost respect and dignity.” Dunlap, supra note 6. When a slave cemetery was discovered at the University of Georgia, a prominent Georgia political leader reminded the public: “They were owned in life, but UGA doesn’t own them in death.”10Blake Aued, Black Leaders Criticize UGA over Slave Graves at Baldwin Hall, Flagpole (Mar. 4, 2017), https://flagpole.com/news/in-the-loop/2017/03/04/black-leaders-criticize-uga-over-slave-graves-at-baldwin-hall [perma.cc/X29N-R3PD]. The author of the statement was Michael Thurmond, Georgia’s former labor commissioner and the current chief executive of the state’s fourth most populous county. Mark Niesse, Mike Thurmond Wins DeKalb County CEO Race, Atlanta J.-Const. (Nov. 8, 2016), https://www.ajc.com/news/local-govt–politics/mike-thurmond-wins-dekalb-county-ceo-race/IothDnqv1IfymWkHXgR3uO [perma.cc/XP65-S33H].

The topic of posthumous interests is not new. Indeed, it has long pervaded legal doctrine. Over a century ago, Justice Joseph Lumpkin III of the Georgia Supreme Court observed that “the law—that rule of action which touches all human things—must touch also this thing of death.”11Louisville & Nashville R.R. Co. v. Wilson, 51 S.E. 24, 25 (Ga. 1905). And while the jurist offered that observation in an opinion about whether a railroad company’s negligence caused the disfigurement of a corpse,12Id. at 24. the statement is no less apt with respect to death’s less corporeal, more metaphysical dimensions. Even after life’s final hour, important legal questions about human dignity, creations, reputation, will, and equality abound.13See Daniel Sperling, Posthumous Interests: Legal and Ethical Perspectives (2008); Fred O. Smith, Jr., The Constitution After Death, 120 Colum. L. Rev. 1471 (2020) (discussing ways that law protects and undermines dignity, reputational interests, creations, will, equality, and spirituality after death); Don Herzog, Defaming the Dead (2017) (assessing ways that American law inadequately protects reputational interests after death); Ray D. Madoff, Immortality and the Law: The Rising Power of the American Dead (2010) (describing the legal interests of the dead and contending that these legal protections have unduly accreted over time). Law confronts these questions by means of torts,14See Restatement (Second) of Torts § 868 cmt. a (Am. L. Inst. 1979). contracts,15See, e.g., Tex. Health & Safety Code Ann. § 711.002(g) (West 2017). trusts and estates,16See, e.g., Wright v. Zeigler, 1 Ga. 324, 346 (1846); Burton v. Yeldell, 30 S.C. Eq. (9 Rich. Eq.) 9, 15 (Ct. App. 1856); see also Knost v. Knost, 129 S.W. 665, 666 (Mo. 1910) (identifying a “right to testamentary disposition”). intellectual property,17See 1 J. Thomas McCarthy & Roger E. Schechter, The Rights of Publicity and Privacy § 1:3, at 4–5 (2021 ed. 2021); 17 U.S.C. § 304(a) (permitting the copyrighting of works created before 1978 for up to ninety-five years after the death of an author). criminal law,18See Idaho Code § 18-4801 (2016); Kan. Stat. Ann. § 21-6103 (Supp. 2019); La. Stat. Ann. § 14:47 (2016); Nev. Rev. Stat. § 200.510 (2019); N.D. Cent. Code § 12.1-15-01 (2012); Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 771 (2020); see also 4 Charles E. Torcia, Wharton’s Criminal Law § 524, at 182–83 (15th ed. 1996). freedom of information,19Nat’l Archives & Records Admin. v. Favish, 541 U.S. 157, 168–69 (2004). civil procedure,20Robertson v. Wegmann, 436 U.S. 584, 588–90 (1978). evidentiary rules,21Swidler & Berlin v. United States, 524 U.S. 399 (1998). constitutional law,22Smith, supra note 13. and even antidiscrimination law.23Mark E. Wojcik, Discrimination After Death, 53 Okla. L. Rev. 389, 390 (2000); Long v. Mountain View Cemetery Ass’n, 278 P.2d 945, 946 (Cal. Dist. Ct. App. 1955); People ex rel. Gaskill v. Forest Home Cemetery Co., 101 N.E. 219, 220–21 (Ill. 1913); Rice v. Sioux City Mem’l Park Cemetery, 60 N.W.2d 110, 115–16 (Iowa 1953). Law, therefore, regularly depends on an accounting of posthumous interests.24Throughout this Article, the term “law” is deployed in three ways: law as mandate, law as mirror, and law as method. What does extant law require with respect to our memory and will when we die? What values are reflected in those legal assessments? And how can we better apply those reflected principles both in law and life? Sometimes, courts are asked to decide whether an alleged offense against a deceased person was “outrageous,”25Model Penal Code § 250.10 cmt. 2 (Am. L. Inst. 1962). “[un]reasonable,”26E.g., Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2927.01(B) (LexisNexis 2019). or “reckless.”27Restatement (Second) of Torts § 868 cmt. a (Am. L. Inst. 1979). Other times, courts must balance interests of the living against the dignitary, reputational, or privacy interests of the dead. In these cases, courts ask whether the reason for a disturbance of the decedent’s interests are “adequa[te]” or “compelling.”28See, for example, Ga. Code Ann. § 36-72-8 (2019), which instructs decisionmakers to consider, when receiving an application to disinter human remains, “[t]he adequacy of the applicant’s plans for disinterment and proper disposition of any human remains or burial objects” and “[a]ny other compelling factors which the governing authority deems relevant.” The statute also requires “[t]he balancing of the applicant’s interest in disinterment with the public’s and any descendant’s interest in the value of the undisturbed cultural and natural environment.” Id. In other instances, it is policymakers who explicitly or implicitly engage in this type of balancing. Policymakers determine which lawsuits survive the death of a party, for example.29Robertson v. Wegmann, 436 U.S. 584, 588–90 (1978). And more broadly, they create statutory and regulatory mandates that govern the treatment of cemeteries, human remains, images, estates, reputations, and personal information.30See, e.g., Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, 25 U.S.C. §§ 3001–3013. See generally Smith, supra note 13 (identifying long-standing legal protections for the dead).

Despite the important legal contexts in which these assessments take place, there is limited legal commentary about how to weigh posthumous legal interests as a class.31Most writing in this area focuses on specific subsets of posthumous interests (i.e., reputation, property, or body). Don Herzog, for example, has written about the reputational interests of the dead, especially in the immediate aftermath of their death. His key examples include someone lying about someone at a funeral and someone placing false, stigmatizing information in an obituary. Herzog, supra note 13 (arguing for a broader set of laws banning the defamation of the dead). Moreover, authors have written thoughtfully about the law of trusts and estates—an area that by its nature focuses on the interests and will of dead persons. See, e.g., Lawrence M. Friedman, Dead Hands: A Social History of Wills, Trusts, and Inheritance Law (2009) (examining the history of the law of posthumous property transfer and exploring what that history teaches about the changing nature of human relationships); David Horton, Indescendibility, 102 Calif. L. Rev. 543, 577 (2014); Tanya K. Hernández, The Property of Death, 60 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 971, 972 (1999) (concluding two decades ago that “the legal system ha[d] not adequately addressed the need for decedent autonomy in confronting death and defining family”). Further, a few authors have written about questions related to interment and burial. Tanya Marsh, The Law of Human Remains (2016); Norman L. Cantor, After We Die: The Life and Times of the Human Cadaver (2010); Christine Quigley, The Corpse: A History (1996); Percival E. Jackson, The Law of Cadavers and of Burial and Burial Places (2d ed. 1950). Andrew Gilden has written more broadly about legal models of “legacy stewardship” and applied lessons from those models to the context of deceased persons’ digital media accounts. The Social Afterlife, 33 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 329, 332–33 (2020). Those who have written about posthumous legal interests have tended to narrow their inquiries to the “‘newly-dead’ as opposed to the ‘long-dead.’”32Sperling, supra note 13, at 1 (“[This] book is mainly concerned with the ‘newly dead’ as opposed to the ‘long-dead.’”). An exception is Ray Madoff, who argues that the dead control the living for longer periods of time in growing and concerning ways. See Madoff, supra note 13. And even less still has been written about the ways that treatment of the dead interacts with identity-based subordination.33Wojcik, supra note 23, at 400; Smith, supra note 13, at 1518. This Article fills those gaps. Are there common principles, patterns, or trends to help us decide what’s “outrageous” and what’s “reasonable” treatment of the dead? How does one determine which kinds of treatment deserve approbation or opprobrium? And how should factors like time, historic subordination, and changing egalitarian values inform the answers to these questions?

As an illustration of the complexity of these kinds of questions, one might reflect on the disparate ways that American culture and law treat the publication of gruesome photographs of dead bodies. The proverbial court of history celebrates the moment in which Emmett Till’s mother allowed Jet magazine to publish a photograph of Till’s horridly maimed corpse during the civil rights era.34Elliott J. Gorn, Let the People See: The Story of Emmett Till (2018); Bracey Harris, Emmett Till Photo Incensed and Inspired a Generation, Clarion Ledger (Aug. 30, 2018, 6:00 AM), https://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/2018/08/30/emmett-till-photo-incensed-and-inspired-generation/1018644002 [perma.cc/9R5C-BRZ8]; When One Mother Defied America: The Photo That Changed the Civil Rights Movement, Time (July 10, 2016, 12:46 PM), https://time.com/4399793/emmett-till-civil-rights-photography [perma.cc/E2VW-8MD6]. The graphic photo powerfully revealed the depraved, murderous, and unimaginably brutish nature of apartheid in the United States. Moreover, with some unease, the United States legally permits people to post photographs of their deceased close friends and family on social media.35Penelope Green, The iPhone at the Deathbed, N.Y. Times (Feb. 18, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/18/style/iphone-death-portraits.html [perma.cc/HU9X-7GZJ]. On the other hand, legal mandates often prevent journalists and others from accessing and publishing gruesome photographs of the dead.36Nat’l Archives & Records Admin. v. Favish, 541 U.S. 157, 160, 166–69 (2004); Megan Bittakis, Tragic Representations: The Curious Contradiction Between Cases Seeking Access to Autopsy and Death Scene Photographs and Cases Regarding the Consequences of Such Photographs Being Published, 40 N. Ky. L. Rev. 161 (2013); Clay Calvert, The Privacy of Death: An Emergent Jurisprudence and Legal Rebuke to Media Exploitation and a Voyeuristic Culture, 26 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 133 (2006). Indeed, courts have criminally indicted individuals for “abuse of corpse” when soldiers and others have taken or published photographs of the dead.37See Bill Chappell, Navy SEAL Demoted for Taking Photo with Corpse of ISIS Fighter, NPR (July 3, 2019, 4:13 PM), https://www.npr.org/2019/07/03/738463353/jury-reduces-navy-seals-rank-for-taking-photo-with-corpse-of-isis-fighter [perma.cc/7M68-PXGB]; see also State v. Condon, 789 N.E.2d 696, 699 (Ohio Ct. App. 2003). What accounts for the varied cultural and legal treatment of acts that seem so similar? Part I of this Article shows how American law engages in culturally contingent assessments when balancing posthumous legal interests. These questions only become more complex when applied to victims of past mass horrors.

We need frameworks for addressing these complex questions. And because law has dealt with posthumous legal interests for centuries (at least), legal analysis can play a critical role in constructing these frameworks. Part II of this Article demonstrates how law traditionally values the decedent’s will, relationships, motives, and culpability. Generally, three principles are of particular salience in assessing posthumous interests. The first is the consent and will of the deceased person. That is, the deceased person’s consent plays a paramount role in determining the legally permissible disposition of matters reasonably within her control. Second, American legal norms take seriously the nature of the living person’s relationship with the dead person by virtue of factors like kinship, contract, control, and community. Third, the law takes seriously the intentions and motives of the living person who is acting toward (or against) the dead. Remuneration, deception, and harmful intentions are all treated suspiciously when regulating the treatment of dead persons. Part III applies these traditional principles to debates about how to treat violently subordinated mass victims’ dead bodies, burial sites, and images.

In Part IV, this Article focuses attention on the role of time and equality in posthumous legal assessments, demonstrating the law’s veneration of our preserved collective memory and its embrace of egalitarian norms in the twentieth century. With regard to time, this Article argues that in American law, any specific individual’s memory and dignitary interests tend to diminish over time. By contrast, the law tends to concern itself with the preservation of collective memory and dignity long after death. This is illustrated by laws governing historical preservation, which give more protection to cemeteries and structures over time rather than less.

This Article also shows that egalitarianism and related norms of antisubordination also came to shape the law of the dead in underappreciated ways over the course of the twentieth century. By fostering stigma, fueling terror, and legally estranging individuals from the government, unequal and brutal treatment of the dead can serve as an important site of subordination.38Smith, supra note 13, at 1518–19.

Taken together, these descriptive observations have normative significance. If collective memory is valuable across generations, and if abusing the memory of the dead can serve to perpetuate subordination, then we must be careful about how we remember and treat the abused and the debased dead. One generation’s treatment of the dead can unwittingly advance a previous generation’s subordination. On this theory, when a group is subordinated through acts of mass horror, later generations can become complicit in that horror by exploiting and dishonoring the subjugated peoples’ memory. In building this theory, this Article relies on arguments advanced by George Pitcher, Joel Feinberg, Martha Nussbaum, and Don Herzog. On this account, an individual can experience posthumous harm when someone alters the shape of the decedent’s unique life. In this Article, I invite readers to consider the special implications this theory has when members of a targeted group’s memories are subordinated in a systemic and sustained way.

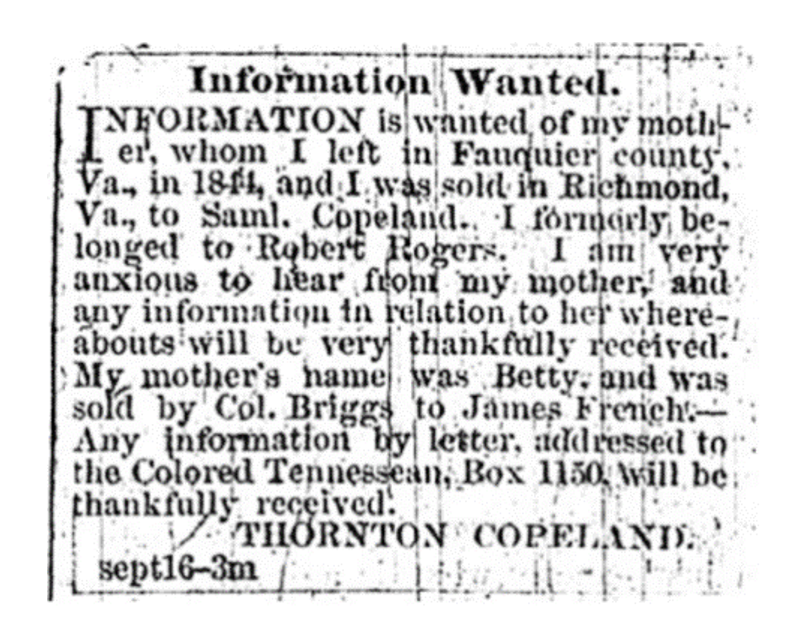

Part IV also outlines a theory of how generations can become complicit in previous generations’ horrors and how this complicity is compounded by corrupted collective memory and lineal alienation. The risk of intergenerational complicity is particularly high in the United States in light of two aspects of this nation’s history. First, powerful actors in previous generations intentionally disrupted America’s collective memory about this nation’s mass human rights abuses.39See Charles Reagan Wilson, Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865–1920 (1980); Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865 to 1913, at 4 (1987). Monuments honoring colonizers and Confederates outnumber memorials to the colonized, the captured, and the controlled by orders of magnitude. Past subordination shapes our present memory. Second, America has a significant history of what I will call “lineal alienation.” By lineal alienation, I mean ways that violent, identity-based subordination has disrupted some individuals’ relationships with their descendants.40This concept is deeply related to, and distinct from, Orlando Patterson’s profoundly influential conception of “natal alienation.” Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death 5 (1982). Natal alienation has been defined as “the deprivation of rights or claims of birth, of claims on and obligations to parents, and of connection to living blood relations, ancestors, or descendants.” Peggy Cooper Davis, Contested Images of Family Values: The Role of the State, 107 Harv. L. Rev. 1348, 1362 (1994). Building on Patterson’s work, some scholars have also persuasively argued that natal alienation describes America’s treatment of indigenous persons as well. See James P. Sterba, Understanding Evil: American Slavery, the Holocaust, and the Conquest of the American Indians, 106 Ethics 424, 437–38 (1996) (reviewing Laurence Mordekhai Thomas, Vessels of Evil: American Slavery and the Holocaust (1993)); Rebecca Tsosie, Sacred Obligations: Intercultural Justice and the Discourse of Treaty Rights, 47 UCLA L. Rev. 1615, 1662 (2000). By invoking the concept of lineal alienation, I wish to bring attention to the multidirectional effects that accompany the uprooting of persons from their ancestral origins. The ancestor loses access to descendants who can care for her memory, dignity, and legacy. Because of lineal alienation, slaves have fewer living trustees to care for their memories and legacies.

After outlining these descriptive and theoretical claims about time and equality, layered with American history, this Article turns to a related question. To the extent that this theory of time and equality reflects worthy aspirational norms, are there ways that the law can be oriented to better reflect those norms? Part V offers four prescriptions for how legal doctrine and policy can better avoid this kind of intergenerational complicity. First, America’s history of lineal alienation has implications for who should be considered a legally cognizable trustee of the interests of the exploited, subjugated dead. When slave cemeteries are discovered, for example, placing exclusive weight on biological kinship when determining whether someone has a legal claim is troubling, even cruel, in a country that forcedly and routinely separated slaves from their kin. The second reform concerns protection for abandoned cemeteries. I argue that when such cemeteries are disturbed inadvertently, they should not be further disturbed without procedural and substantive protections akin to those that known abandoned cemeteries receive. Third, if courts and lawmakers take the proffered relationship between time, equality, and death seriously, this has implications for what type of conduct is deemed “unreasonable,” “offensive,” and “outrageous,” all of which are important legal terms in the law governing dead bodies and images. Any equitable accounting of these kinds of contextually inflected terms must acknowledge America’s history of violent subordination, legal erasure, and lineal alienation. Fourth, I argue for significant governmental investment in monuments, museums, arts, and other resources designed to counter false, corrupted memories about America’s past.

I. The Cultural Contingency of Posthumous Interests

[C]ourts will not close their eyes to the customs and necessities of civilization in dealing with the dead and those sentiments connected with decently disposing of the remains of the departed which furnish one ground of difference between men and brutes.

—Justice Joseph Lumpkin III41Louisville & Nashville R.R. Co. v. Wilson, 51 S.E. 24, 25 (Ga. 1905).

“Respectful.” “Offensive.” “Ethical.” “Outrageous.” Dueling words like these serve as lodestars and admonitions when the bodies and images of victims of past horrors are unearthed and exposed. When, for example, research revealed that fifty-three skulls on display at a museum at the University of Pennsylvania were those of former slaves from Cuba, the university stated that it was “committed to working through this important process with heritage community stakeholders in an ethical and respectful manner.”42Johnny Diaz, Penn Museum to Relocate Skull Collection of Enslaved People, N.Y. Times (July 29, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/27/us/Penn-museum-slavery-skulls-Morton-cranial.html [perma.cc/R8AH-AQRY]. See generally Ann Fabian, The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America’s Unburied Dead (2010) (profiling nineteenth-century researcher Samuel George Morton, whose extensive collection of human skulls contributed to the pseudoscience of racial superiority); Lisa A. Giunta, Note, The Dead on Display: A Call for the International Regulation of Plastination Exhibits, 49 Colum. J. Transnat’l L. 164 (2010) (criticizing recent museum exhibits for “putting the bodies of the deceased on display for profit” without sufficient consent or respect). And when the University of Georgia (UGA) discovered a badly neglected slave cemetery on its campus, it promised that its treatment of the bodies would be “respectful” and “dignified.”43Univ. of Ga., Report from the Ad Hoc Committee on Baldwin Hall to the Franklin College Faculty Senate 37 (2019), https://www.franklin.uga.edu/sites/default/files/Faculty%20Senate%20ad%20hoc%20committee%20report%204-17-19.pdf [perma.cc/B523-6H4W] [hereinafter UGA Baldwin Hall Report].

Those institutions and others, however, have faced vocal concerns and vehement criticism. Activists at Penn asked the university to repair the damage done by the “unethical acquisition” and exploitation of the crania and, more broadly, called on the university to “remove all images from the Museum’s digital footprint that represent the deceased without consent.”44#PoliceFreePenn: An Abolitionist Assembly (@policefreepenn), Repatriation & Reparations NOW! Restating What We Mean by Abolish the Morton Collection., Medium (Apr. 14, 2021), https://medium.com/@policefreepenn/repatriation-reparations-now-restating-what-we-mean-by-abolish-the-morton-collection-9a67f9206279 [perma.cc/AL7H-KKVS] [hereinafter Abolish the Morton Collection]. At UGA, a faculty committee concluded that it was factually “not possible” to accept the university’s official narrative that the remains were treated in an “exemplary and respectful way.”45UGA Baldwin Hall Report, supra note 43. The report cited, among others, my own father, a Georgia native and a key critic of UGA’s disinterment of the human remains. In a manner that moved me as a descendant of former slaves, a son, and a scholar, he implored the local community at a public forum: “If you can’t get outraged about someone destroying your great-grandparents’ graves, what can you get outraged about?”46Rebecca McCarthy, Panel Wrestles With UGA’s Legacy of Slavery, Flagpole (Mar. 27, 2017), https://flagpole.com/news/city-dope/2017/03/27/panel-wrestles-with-ugas-legacy-of-slavery [perma.cc/L3UE-ZAKH].

Law has a potentially important role in contextualizing and informing these recurring cultural disputes, because law has long been a mode through which Americans have confronted questions about the proper treatment of the dead. For example, there are at least four long-standing “rights” after death in America’s legal tradition: bodily integrity (protection against mutilation and other bodily violations), dignified interment, protection against undignified disturbance once interred, and control over the disposition of one’s property.47Smith, supra note 13, at 1475. Law also protects posthumous interests in privacy and equality. See Weaver v. Myers, 229 So. 3d 1118 (Fla. 2017); 45 C.F.R. § 160.103 (2020) (defining “protected health information” to include identifiable health information regarding patients who have been deceased for fewer than fifty years); see also Smith, supra note 13, at 1518–27.

This Part outlines how courts and policymakers are necessarily called on to assign weight to these posthumous legal interests. That is, they assess which factors add gravity to the decedents’ interests, and which factors diminish those interests. This is true in two ways. First, legal mandates in this area often rely on elements that are culturally contingent or dependent on community sensibilities. These include terms like “outrageous,” “offensive,” “reasonable,” “and “respect.” Second, even when legislatures issue more precise legal rules that protect interests after death, these decisionmakers must choose which aspects of humanity to honor after death, how to honor them, and how to balance those interests against the needs and desires of the living.48As a doctrinal matter, extracting these principles can help bring clarity to the law and offer administrable standards for courts to apply. As a cultural matter, by appreciating what law has tended to deem “reasonable” or “outrageous” with respect to deceased persons, there may be lessons about the dimensions of our shared humanity that are valued after death. In turn, those lessons can help institutions and individuals answer hard cultural questions when the law seems insufficient or uncertain.

A. Culturally Contingent Terms

In his book The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains, cultural historian Thomas Laqueur writes, “[T]he dead have two lives: one in nature, the other in culture.”49Thomas W. Laqueur, The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains 10 (2015); see also Mary L. Dudziak, Death and the War Power, 30 Yale J.L. & Humans. 25, 38 (2018). Laqueur’s work canvasses the many ways that humans have shown reverence to human bodies across time and place.50Laqueur, supra note 49; see also Cantor, supra note 31; Quigley, supra note 31. Among the norms that vary are the suitability of certain sites of burial, the acceptability of cremation, and the relative importance of individually marked tombstones. He observes, to be sure, that cultures appear to have universal respect for human remains.51See Laqueur, supra note 49, at 40; see also Smith, supra note 13, at 1507 (“Because cultures almost universally assign human meaning to the dead and adopt conventions to protect the dead, violations of these conventions dishonor that meaning. And violating that meaning is thereby a form of dishonoring shared human dignity.” (footnote omitted)). But what constitutes respectful conduct is far from fixed. Consistent with these observations, to the extent that legal mandates concerning the dead turns on what “outrages” or “offends,” these mandates are imbued with cultural values and norms. Because terms like this pervade the law of the dead, this body of law offers a rich site of study.

Included in this discussion are torts and crimes that focus on familial outrage or distress. One might question whether those elements belong in a discussion about posthumous legal interests. To the extent that a law turns on the distress of living family members, how could such a law furnish a meaningful example of a court weighing interests after death? I include claims based on familial outrage and anguish for two reasons. First, the history of familial claims such as “abuse of corpse” are historically bound up in the idea that families are surviving trustees for the interests of the dead. In the 1820 English case Gilbert v. Buzzard, Lord Stowell (Sir William Scott) noted the long-standing right of the dead “to be returned to [their] parent earth for dissolution[] and to be carried there for that purpose in a decent and inoffensive manner.”52(1820) 161 Eng. Rep. 1342, 1348; 3 Phill. Ecc. 333, 352–53. Relying on that right, American courts recognized a living person’s “quasi property” interest in the dead bodies of family members to facilitate this right of burial.53Pierce v. Proprietors of Swan Point Cemetery, 10 R.I. 227, 238–39 (1872). This “quasi property” interest in the body arises from “duties to perform towards it arising out of our common humanity,” as a leading nineteenth-century case put it.54Id. at 242–43. Second, and perhaps more importantly, legal protection of a surviving family from outrage, anguish, and offense is itself a useful site of study. These protections invite reflection on the cultural norms that shape who (including which family members) can serve as trustees for dead persons, whose outrage is legally cognizable, and what mental anguish is deemed foreseeable or compensable.

1. “Outrage”

“Outrage” is often an element of criminal and civil claims against those who commit abuses against the dead. Laws that prohibit the abuse of corpses and desecration of grave sites tend to focus on conduct that would likely outrage the community or family. Tennessee courts, for example, have held that “[t]he gravamen of the offense” of indecently disposing of a dead body “is that the facts supporting the crime be such that ‘the feelings and natural sentiments of the public would be outraged.’”55Wilks v. State, No. E2002-00846-CCA-R3-PC, 2002 WL 31780720, at *2 (Tenn. Crim. App. Dec. 13, 2002) (quoting John S. Herbrand, Annotation, Validity, Construction, and Application of Statutes Making It a Criminal Offense to Mistreat or Wrongfully Dispose of Dead Body, 81 A.L.R.3d 1071, 1073 (1977)). A Tennessee statute similarly defines desecration of a burial site as “defacing, damaging, polluting or otherwise physically mistreating in a way that the person knows or should know will outrage the sensibilities of an ordinary individual likely to observe or discover the person’s action.”56Tenn. Code Ann. § 39-17-301 (Supp. 2020); see also id. § 39-17-311(a)(1) (2018).

This reliance on outrage is neither new nor unique. In the 1939 case State v. Bradbury, Maine’s high court upheld the conviction of a man for indecently burning his sister’s dead body “in such a manner that, when the facts should in the natural course of events become known, the feelings and natural sentiments of the public would be outraged.”579 A.2d 657, 659 (Me. 1939). This language was later codified. See Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 17–A, § 507 (2006). Similarly, Ohio law bans abuses of dead bodies that reasonably outrage families or community sensibilities.58Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2927.01(B) (LexisNexis 2019). Laws in Colorado, Delaware, Hawaiʻi, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia also ban conduct against dead persons or burial sites that outrage “community sensibilities.”59Colo. Rev. Stat. § 18-9-113 (2020); Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§ 711-1107 to -1108 (LexisNexis 2016 & Supp. 2020); 18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 5509 (West 2015); W. Va. Code Ann. § 61-8-14 (LexisNexis 2020). Delaware law bans desecration of “object[s] of veneration,” Del. Code tit. 11, § 1331 (2021), which has been used to support prosecutions for the desecration of grave sites. See State v. Melvin, No. C.R. 1507023761, 2016 WL 616979, at *1 (Del. Ct. Com. Pl. Feb. 5, 2016). Moreover, the Model Penal Code recommends that states criminalize actions that “treat[] a corpse in a way that he knows would outrage ordinary family sensibilities.”60Model Penal Code § 250.10 (Am. L. Inst. 1962).

In the civil context, treatment of the dead often intersects with the tort of “intentional infliction of emotional distress”—a claim that also requires “outrage.” For plaintiffs to prove “intentional infliction of emotional distress, or outrageous conduct,” there are three key elements: “(1) the conduct complained of must be intentional or reckless; (2) the conduct must be so outrageous that it is not tolerated by civilized society; and (3) the conduct complained of must result in serious mental injury.”61Akers v. Prime Succession of Tenn., Inc., No. E2009-02203-COA-R3-CV, 2011 WL 4908396, at *21 (Tenn. Ct. App. Oct. 17, 2011) (quoting Bain v. Wells, 936 S.W.2d 618, 622 (Tenn. 1997)), aff’d, 387 S.W.3d 495 (Tenn. 2012). “Generally, the case is one in which the recitation of the facts to an average member of the community would arouse his resentment against the actor, and lead him to exclaim, ‘Outrageous.’”62Id.

Facts that have sustained this type of tort action include a case where a person disinterred a body, doused the body with “caustic chemical,” and then left parts of the body in the forest.63Gray Brown-Serv. Mortuary, Inc. v. Lloyd, 729 So. 2d 280, 285–86 (Ala. 1999). Likewise, trespassing onto a cemetery and damaging a tombstone has sustained an outrage claim.64Whitt v. Hulsey, 519 So. 2d 901, 903–06 (Ala. 1987). A court has also sustained an outrage claim where an undertaker refused to return to a widow her deceased husband’s body in order to coax her into buying a more expensive casket. 65Levite Undertakers Co. v. Griggs, 495 So. 2d 63, 64 (Ala. 1986). And more recently, a federal court sustained an outrage claim in a high-profile case involving Natalee Holloway, an eighteen-year old Alabama resident who disappeared while vacationing in Aruba. A media outlet allegedly misled Holloway’s mother about whether bones and other biological material were her daughter’s, knowing the bones likely belonged to an animal. “Such conduct is plausibly extreme and outrageous and so severe that no reasonable person could be expected to endure it under Alabama law.”66Holloway v. Oxygen Media, LLC, 361 F. Supp. 3d 1213, 1225 (N.D. Ala. 2019).

The concept of outrage has also been invoked in equitable cases concerning whether to disinter bodies. One notable example is Judge Benjamin Cardozo’s 1926 opinion in Yome v. Gorman.67152 N.E. 126, 127 (N.Y. 1926). In that case, a widow requested that the owners of a religious cemetery disinter her deceased husband so that she could bury him in a plot next to one she had purchased for her own burial. Other close kin supported her request. But, writing for the New York Court of Appeals, Judge Cardozo explained that only in some “rare emergency” would it be acceptable for a court “to take a body from its grave in consecrated ground and put it in ground unhallowed if there was good reason to suppose that the conscience of the deceased, were he alive, would be outraged by the change.”68Yome, 152 N.E. at 128. The opinion instructed the trial court to privilege evidence of the decedent’s wishes on remand. For decades thereafter, Judge Cardozo’s opinion served as “the leading case on this subject”; relying on Yome, other courts sought to avoid moves that would “outrage” decedents if they were alive.69Goldman v. Mollen, 191 S.E. 627, 633 (Va. 1937); Friedman v. Gomel Chesed Hebrew Cemetery Ass’n, 92 A.2d 117, 119 (N.J. Super. Ct. Ch. Div. 1952).

2. “Offensive”

When laws regulate dead bodies and matters of interment, another element or term is “offensiveness.” The term is much less common than “outrage” but is nonetheless a long-standing feature of this body of law. An early invocation of this element can be found in the 1912 case Seaton v. Commonwealth.70149 S.W. 871 (Ky. 1912). Tanya Marsh relies on this case as evidence that much of the law in this area is a matter of custom and common law. Marsh, supra note 31, at 4 n.4. The case is also discussed in Ellen Stroud, Law and the Dead Body: Is a Corpse a Person or a Thing?, 14 Ann. Rev. L. & Soc. Sci. 115, 121 (2018). In that case, an impoverished father buried his prematurely born son in a self-created wooden coffin in his backyard rather than a cemetery.71Seaton, 149 S.W. at 871. While he was convicted for indecently burying his son, the Court of Appeals of Kentucky (then Kentucky’s highest court) reversed, finding that the interment was not sufficiently offensive as a matter of custom. It reasoned,

The custom of the country imposed upon [the] appellant only the duty of decently burying his child; that is, it must be properly clothed when being taken to the place of burial, and then placed in the ground or tomb, so that it will not become offensive or injurious to the lives of others. He may not cast it into the street, or into a running stream, or into a hole in the ground, or make any disposition of it that might be regarded as creating a nuisance, be offensive to the sense of decency, or be injurious to the health of the community.72Id. at 873.

The defendant’s actions comported with this duty even if, the court gratuitously added, he was “a man utterly lacking in parental instincts.”73Id.

Today, some statutes formally incorporate offensiveness as an element of crimes concerning the abuse of dead bodies. In Arkansas, for example, it is illegal to “[p]hysically mistreat[] or conceal[] a corpse in a manner offensive to a person of reasonable sensibilities.”74Ark. Code Ann. § 5-60-101(a)(2) (2016). The phrase “in a manner offensive to a person of reasonable sensibilities” means, among other things, “in a manner that is outside the normal practices of handling or disposing of a corpse.”75Id. Likewise, in Tennessee, it is a felony to “[p]hysically mistreat[] a corpse in a manner offensive to the sensibilities of an ordinary person.”76Tenn. Code Ann. § 39–17–312 (2018). In Texas, it is a crime if one “disinters, disturbs, damages, dissects, in whole or in part, carries away, or treats in an offensive manner a human corpse.”7712 Tex. Jur. 3d Cemeteries § 61, at 68–69 (2019). Moreover, it is a crime in Texas to vandalize, damage, or treat “in an offensive manner the space in which a human corpse has been interred or otherwise permanently laid to rest.”78Id.

3. Reasonableness

For over a century, the tort of negligence has been invoked when persons or institutions unreasonably mutilate a dead body or otherwise interfere with a burial. One leading case on the subject is Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co. v. Wilson.7951 S.E. 24, 25 (Ga. 1905). In 1903, a woman bought a train ticket to transport her husband’s body from Atlanta to a small town in eastern Georgia, where he was to be buried. When the train carrying the body reached a junction point, the railroad company placed the body on an open platform, where it lay in the rain unprotected for several hours. The body became “soaked and otherwise mutilated.”80Wilson, 51 S.E. at 24. Georgia courts found that this conduct was grossly negligent and allowed the widow to sue for damage to the $75 coffin and shroud, as well as humiliation and mental anguish.81Id. at 24–25.

Wilson represents a broader class of cases against those who negligently perform their duty to care for dead bodies or otherwise negligently interfere with interment. And while the plaintiff in Wilson alleged “gross negligence,” some jurisdictions have allowed recovery for ordinary negligence in this context.82See, e.g., Del Core v. Mohican Historic Hous. Assocs., 837 A.2d 902, 905 (Conn. App. Ct. 2004); Crawford v. J. Avery Bryan Funeral Home, Inc., 253 S.W.3d 149, 159–60 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2007). Under the Restatement (Second) of Torts, “One who intentionally, recklessly or negligently removes, withholds, mutilates or operates upon the body of a dead person or prevents its proper interment or cremation is subject to liability to a member of the family of the deceased who is entitled to the disposition of the body.”83Restatement (Second) of Torts § 868 (Am. L. Inst. 1979).

Culturally contingent assessments about how the dead are to be treated inflect our understanding of the gravity of the plaintiff’s loss, overriding the physical-injury requirement for negligence claims. In most negligence cases, it is highly unusual to allow recovery for mental anguish caused by ordinary negligence absent a showing of physical injury. As explained in the 1984 edition of Prosser and Keeton’s treatise, “Where the defendant’s negligence causes only mental disturbance, without accompanying physical injury, illness or other physical consequences, and in the absence of some other independent basis for tort liability, the great majority of courts still hold that in the ordinary case there can be no recovery.”84W. Page Keeton et al., Prosser and Keeton on the Law of Torts § 54, at 361 (5th ed. 1984) (footnote omitted). Yet treatment of dead bodies represents an exception to that general rule. Courts often allow recovery “for negligent embalming, negligent shipment, running over the body, and the like, without such circumstances of aggravation.”85Id. at 362 (footnotes omitted); see, e.g., Keaton v. G.C. Williams Funeral Home, Inc., 436 S.W.3d 538, 543 (Ky. Ct. App. 2013); Brown v. Bayview Crematory, LLC, 945 N.E.2d 990, 994 (Mass. App. Ct. 2011); Vasquez v. State, 206 P.3d 753, 765 n.10 (Ariz. Ct. App. 2008); Blackwell v. Dykes Funeral Homes, Inc., 771 N.E.2d 692, 697 (Ind. Ct. App. 2002); Guth v. Freeland, 28 P.3d 982, 988 (Haw. 2001); Kelly v. Brigham & Women’s Hosp., 745 N.E.2d 969, 978 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001); Contreraz v. Michelotti–Sawyers, 896 P.2d 1118, 1120–21 (Mont. 1995); Brown v. Matthews Mortuary, Inc., 801 P.2d 37, 44 (Idaho 1990); Moresi v. Dep’t of Wildlife & Fisheries, 567 So. 2d 1081, 1095–96 (La. 1990). As one federal court recently put it,

[A]lthough courts have traditionally been reluctant to allow negligence actions where only emotional damages are claimed, the more modern view supports the position taken by plaintiff in the instant case and recognizes an ordinary negligence cause of action arising out of the next of kin’s right to possession of a decedent’s remains.86Cochran v. Securitas Sec. Servs. USA, 59 N.E.3d 234, 246–49 (Ill. App. Ct. 2016).

4. Respect

The degree of legal protection that cemeteries receive sometimes depends expressly on the public’s recognition and respect. This legal standard is most evident in cases involving disinterment or destruction of gravesites. That is, among the many ways that a cemetery can lose legal protection is that members of the public no longer treat it as a cemetery. In the early 1920s, for example, in South Carolina, a plaintiff sued developers that disturbed a site containing his family’s human bodies. The developers alleged that the cemetery had been abandoned and therefore merited significantly less legal protection than an active cemetery. When the issue reached the South Carolina Supreme Court, that tribunal articulated its goal of approximating public sentiment on this delicate subject. It explained that

laws do, or should, set forth the sentiment of the people who are subject to them. This is particularly true under a government like ours. From the time of Abraham, the places where the dead were buried have been considered sacred and inviolate. All nations respect the graves of the dead.87Frost v. Columbia Clay Co., 124 S.E. 767, 768 (S.C. 1924).

In determining whether the defendants had illegally disturbed graves, the court accordingly cited a legal treatise for the proposition that “where a cemetery has been so neglected as entirely to lose its identity as such, and is no longer known, recognized, and respected by the public as a cemetery, it may be said to be abandoned.”88Id. at 770 (citations omitted). This standard for abandonment has been cited in number of states across the country, including Alabama, Kansas, New York, and Pennsylvania.89Boyd v. Brabham, 414 So. 2d 931, 935 (Ala. 1982); State ex rel. Stephan v. Lane, 614 P.2d 987, 997–98 (Kan. 1980); Ferncliff Cemetery Ass’n v. Town of Greenburgh, 124 N.Y.S.3d 61, 67 (N.Y. App. Div. 2020); In re First Evangelical Lutheran Church, 13 Pa. D. & C.2d 93, 99 (Ct. Quarter Sess. Westmoreland Cnty. 1957).

B. Culturally Contingent Balancing

Some legal regulations expressly call on decisionmakers or judges to balance the need for respectful treatment of the dead against other important public interests. This kind of balancing is particularly pronounced in cases involving disinterment. Under a Georgia statute, for example, when an entity applies for a permit to disturb an abandoned cemetery, local authorities are to balance “the applicant’s interest in disinterment with the public’s and any descendant’s interest in the value of the undisturbed cultural and natural environment.”90Ga. Code Ann. § 36-72-8 (2019). Among other factors, local authorities are also required to consider “[t]he adequacy of the applicant’s plans for disinterment and proper disposition of any human remains or burial objects” as well as “[a]ny other compelling factors which the governing authority deems relevant.”91Id. And until recently, Iowa law required that upon determining whether to permit disinterment, “[d]ue consideration . . . shall be given to the public health, the dead, and the feelings of relatives.”92Iowa Code § 144.34 (2020) (amended 2020). The revised statute de-emphasizes the will of the decedent. See Iowa Code § 144.34 (2021) (“Due consideration . . . shall be given to the public health, the preferences of a person authorized to control final disposition of a decedent’s remains . . . , and any court order.”); cf. Gilden, supra note 31 (encouraging decentering the decedent when stewarding a person’s legacy after death and instead focusing more on the decedent’s social context).

More frequently, these kinds of balancing standards have been incorporated by way of the common law. These balancing tests reflect cultural choices about how to honor and prioritize competing desires and needs. Under Illinois law, for example,

[i]t is the policy of the law, except in cases of necessity or for laudable purposes, that the sanctity of the grave should be maintained, and that a body once suitably buried should remain undisturbed, and a court will not ordinarily order or permit a body to be disinterred unless there is a strong showing that it is necessary and that the interests of justice require.93Fischer’s Est. v. Fischer, 117 N.E.2d 855, 857 (Ill. App. Ct. 1954).

Over the past century, various balancing tests for proper disinterment have been adopted in California,94Maffei v. Woodlawn Mem’l Park, 29 Cal. Rptr. 3d 679, 685–87 (Ct. App. 2005). Colorado,95Wolf v. Rose Hill Cemetery Ass’n, 832 P.2d 1007, 1009 (Colo. App. 1991). Minnesota,96Spadaro v. Catholic Cemeteries, 330 N.W.2d 116, 118–19 (Minn. 1983). Mississippi,97Hood v. Spratt, 357 So. 2d 135, 137 (Miss. 1978). New Mexico,98Theodore v. Theodore, 259 P.2d 795, 797 (N.M. 1953). and Pennsylvania.99Pettigrew v. Pettigrew, 56 A. 878, 880 (Pa. 1904). Among the most common factors in these tests include the wishes of the decedent and the relationship between the decedent and the person seeking to disinter the body. Also common are appeals to the public interest: California law instructs courts to consider “the interests of the public”;100Maffei v. Woodlawn Mem’l Park, 29 Cal. Rptr. 3d 679, 685–86 (Ct. App. 2005). in Colorado, the “[i]mpact of disinterments on others”;101Wolf v. Rose Hill Cemetery Ass’n, 832 P.2d 1007, 1009 (Colo. App. 1991). and in New Mexico, the “public interest.”102Theodore, 259 P.2d at 795. In Minnesota, courts are asked to weigh “[t]he strength of the reasons offered both in favor of and in opposition to reinterment.”103Spadaro v. Catholic Cemeteries, 330 N.W.2d 116, 118–19 (Minn. 1983).

II. Traditional Principles of Posthumous Interests

Our legal system allows the dead to control the living, at least up to a point.

—Lawrence Friedman104Friedman, supra note 31, at 125.

There are common principles that structure how courts weigh and enforce posthumous legal interests. First, the clear, good-faith wishes of the decedent are generally honored when practicable. Second, the law takes seriously the relationship between the decedent and the living person or institution attempting to act toward, or on behalf of, the dead. Law confers agency and obligations based on conceptions of kinship, contract, control, and community. Third, motive and fault are important. American law encourages suspicion when a living person is profiting off a dead person without consent; acts with deception; is knowingly, recklessly, or unreasonably causing harm; or killed the decedent.

A. Intention

American law is deeply attentive to fulfilling the expressed will of the decedent on matters reasonably within the decedent’s control.105Professor Gilden calls this the “freedom of disposition model.” See Gilden, supra note 31, at 333. Through wills and trusts, for example, people have considerable power of “testimonial disposition,” directing to whom one’s property will go, how it should get there, and—to some extent—how that property can be used. This right of testimonial disposition has been described as “one of the most essential sticks in the bundle of rights.”106See Hodel v. Irving, 481 U.S. 704, 716 (1987). The default rule, with some important exceptions, is that most property is posthumously transferable.107Horton, supra note 31, at 577. As the Supreme Court expressed in Hodel v. Irving, “In one form or another, the right to pass on property—to one’s family in particular—has been part of the Anglo-American legal system since feudal times.”108481 U.S. at 716. And as one 1856 South Carolina court put it, “Few rights are regarded with so much jealousy as the right of testamentary disposition of one’s own property . . . .”109Burton v. Yeldell, 30 S.C. Eq. (9 Rich. Eq.) 9, 15 (1856).

The American legal system also gives significant weight to decedents’ directives about their interment. In the words of a New York court in 1880, “[T]he dead themselves now have rights, which are committed to the living to protect,” including “the undisturbed rest of their own remains.”110Thompson v. Hickey, 8 Abb. N. Cas. 159, 167 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1880). This is not to say these desires or testaments are always followed; sometimes other interests take precedent.111See, e.g., Shipley Estate, 49 Pa. D. & C.2d 331 (Ct. Com. Pl. 1970). In that case, a deceased man’s will stated his desire to be buried in Tennessee near his extramarital paramour. But his wife, who was in Pennsylvania, wished for him to be buried in that state instead. A court ruled in favor of the wife, citing the decedent’s deceit. “[B]ecause of the deceitful double life in which decedent encased himself, it is apparent to this court that he forfeited any right that he may have had to have his desires as to his burial honored, since such desires conflict with those of his lawful widow.” Id. at 338. See also Lior Jacob Strahilevitz, The Right to Destroy, 114 Yale L.J. 781, 784 (2005) (“[M]any American courts have rejected the notion that an owner has the right to destroy that which is hers, particularly in the testamentary context.”). But it is nonetheless an indispensably important interest that American law regularly takes into account when enforcing death rights. “A person has the right to control the disposition of his or her own remains without the predeath or postdeath consent of another person,” avers a Washington statute.112Wash. Rev. Code § 68.50.160 (2020). Statutes in Oklahoma and South Dakota have similar language.113Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 1151 (2020); S.D. Codified Laws § 34-26-1 (2011). Indeed, laws respecting decedents’ express wishes as to interment are quite common.114See, e.g., Ark. Code Ann. § 20-17-102 (2018); Cal. Health & Safety Code § 7100.1 (West 2007); Colo. Rev. Stat. § 15-19-104 (2020); D.C. Code § 3-413 (2021); Del. Code tit. 12, § 264 (2021); Idaho Code § 54-1139 (2017); Ind. Code § 29-2-19-9 (2020); Md. Code Ann., Health–Gen. § 5-509 (LexisNexis Supp. 2020); Minn. Stat. § 149A.80 (2020); Neb. Rev. Stat. § 38-1426 (2016); Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 1151 (2020); Or. Rev. Stat. § 97.130 (2019); 20 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 305(a) (West Supp. 2020); S.D. Codified Laws § 34-26-1 (2011); Tex. Health & Safety Code Ann. § 711.002(g) (West 2017); Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 18, § 9702(a)(16) (2017); Wash. Rev. Code § 68.50.160 (2020); Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 2-17-101 (2021).

B. Relationship

When assessing the weight of posthumous legal interests, another core variable is the relationship between the living person(s) and the decedent. That is, what was the relationship between the person who died, and the person seeking to act toward, or on behalf of, the dead person? The nature of this relationship influences two types of legal consequences. First, it can determine the scope of the living person’s legal agency to act toward, or on behalf of, the decedent.115Cf. Gilden, supra note 31, at 340 (“Emotional and cultural legacies accordingly do not require planning; they require stewardship.”). Second, some relationships can create certain legal obligations to act toward, or on behalf of, the decedent. The most important categories of these relationships are kinship, contract, control, and shared community.

1. Kinship

Familial ties are an important feature of posthumous legal interests. After death, kinship helps shape the disposition of one’s property, body, and privacy interests. For estates, the familial role is most acute when a person dies intestate. That is, laws specify how assets are to be distributed either when someone dies without a will or when some portion of the decedent’s estate is not covered by a will. Spouses tend to be highest in the distributional chain in this scenario, followed by children.116See, e.g., Unif. Prob. Code § 2-102 (amended 2019), 8 pt. 1 U.L.A. 28 (Supp. 2020) (describing spouse’s share); id. § 2-103, 8 pt. 1 U.L.A. 30 (describing other heirs); Tex. Est. Code Ann. § 201.001 (West 2020). But see Ga. Code Ann. § 53-2-1(c)(1) (2021) (providing that the spouse’s share be the same as the children’s share, but not less than one-third). In the absence of either, intestate distribution often includes other kin, such as parents, siblings, and grandchildren.117Unif. Prob. Code § 2-103 (amended 2019), 8 pt. 1 U.L.A. 30–32. Even when a person does have a will, kinship still matters in some circumstances. All but one state protects spouses even when they are not included expressly in a will. The most common method is through what is called an “elective share,” in which some percentage of the property is distributed to a spouse before the remainder of the will is honored.118See Jeffrey N. Pennell, Individuated Determination of a Surviving Spouse’s Elective Share, 53 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 2473 (2020). Over the past century, the law in this area reflects an increased protection for spouses, in relation to a previously privileged role for offspring. Lawrence Friedman has called this “the shift from emphasis on the bloodline family to the family of affection and dependence.”119Friedman, supra note 31, at 19 (emphases omitted). He attributed this shift to changes in American family structures. Other scholars have attributed this shift to the increased political, economic, and cultural role of women in the United States.120Ronald Chester, From Here to Eternity? Property and the Dead Hand 75 (2007); Mark L. Ascher, But I Thought the Earth Belonged to the Living, 89 Tex. L. Rev. 1149, 1152 (2011) (reviewing Lawrence M. Friedman, Dead Hands: A Social History of Wills, Trusts, and Inheritance Law (2009)).

Kinship also plays a paramount role in terms of one protecting one’s body. This is most apparent when it comes to a decedent’s interment. At the common law, unless a decedent’s wish was “strongly and recently expressed,” the wish of a surviving spouse was paramount.121Pettigrew v. Pettigrew, 56 A. 878, 880 (Pa. 1904); Marsh, supra note 31, at 9. And if unmarried, “the right [to dispose of remains] is in the next of kin in the order of their relation to the decedent, as children of proper age, parents, brothers and sisters, or more distant kin, modified, it may be, by circumstances of special intimacy or association with the decedent.”122Pettigrew, 56 A. at 880. State laws across the country continue to hold that when the decedent has not specified their preferred method of interment in writing, it is close kin who decide.123See, e.g., Ark. Code Ann. § 20-17-102(d)(1) (2018); Cal. Health & Safety Code § 7100 (West 2007); Colo. Rev. Stat. § 15-19-106 (2020); Mo. Rev. Stat. § 194.119 (2016); N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 290:16 (2016); Va. Stat. Ann. § 54.1-2807.01 (2019). Here, too, spouses tend to be considered the closest kin in this scenario, followed by other kin such as children, parents, and siblings. Families are also centered with regard to disinterment.124Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 32-1365.02 (2016); Tex. Health & Safety Code Ann. § 711.004 (West Supp. 2020).

This control over interment includes the right to sue when someone interferes.125Restatement (Second) of Torts § 868 (Am. L. Inst. 1979). Moreover, family members are sometimes centered in criminal laws banning the abuse of a corpse, given that the Model Penal Code recommends the prohibition of conduct that “would outrage ordinary family sensibilities.”126Model Penal Code § 250.10 (Am. L. Inst. 1962).

Familial relationships also create obligations toward dead bodies. Under Alaska law, “Every needy person . . . shall be given a decent burial by the spouse, children, parents, grandparents, grandchildren, or siblings of the needy person, if they, or any of them, have the ability to do so, in the order named.”127Alaska Stat. § 47.25.230 (2020). Even more directly, there are criminal laws against “abandonment” or “concealment” of dead bodies in ways that make it impossible for them to be interred properly.128Torcia, supra note 18, § 524 (“At common law, it is a nuisance to fail to provide a decent burial for a person to whom the defendant owes such a duty.”). And as the 2002 Missouri case of State v. Bratina exemplifies, families tend to have particular duties not to abandon their kin.12973 S.W. 3d 625 (Mo. 2002) (en banc). In Bratina, a man was charged with abandonment for failing to report the death of his dead wife, and leaving her in their home. He argued that the state’s abandonment statute was unconstitutionally vague. The challenged law stated that “[a] person commits the crime of abandonment of a corpse if that person abandons, disposes, deserts or leaves a corpse without properly reporting the location of the body to the proper law enforcement officials in that county.”130Bratina, 73 S.W.3d at 626. The court concluded that the law was sufficiently clear that close kin have a duty to report deaths promptly.131Id. at 627–28. “The concept of ‘abandonment’ in the statute,” the court explained, “clearly is based upon a person having an interest in, or duty with respect to, the body.”132Id. at 627. “Bratina is not a mere bystander. The body is that of his wife, the body was in his household, and he is the next of kin,” the court reasoned.133Id.

Furthermore, families are authorized to protect the privacy interests of the dead. On questions of medical privacy, families have the power to object to the release of information about their kin under federal regulations and under state law.134See 45 C.F.R. § 160.103 (2020); Weaver v. Myers, 229 So. 3d 1118, 1127–32 (Fla. 2017). In addition, some states have recognized various notions of privacy that prevent the unauthorized distribution of photographic images of a corpse. In Reid v. Pierce County, the Washington Supreme Court permitted families to sue a county for invasion of privacy for publicly displaying photographs of their kin’s corpses without authorization.135961 P.2d 333, 335 (Wash. 1998) (en banc). And in State v. Condon, the Ohio Court of Appeals upheld the conviction of a photographer who, without permission, took photographs of dead bodies in a morgue with the intention of making them public.136State v. Condon, 789 N.E.2d 696 (Ohio Ct. App. 2003). The outcome in Condon might have been different, however, if the photographer had obtained permission from the family (or from the predeath consent of the dead subjects). The Court of Appeals explained,

Had Condon been able, therefore, to devise a means of obtaining either legal authorization or the consent causa mortis of his subjects (or perhaps even the posthumous consent of their families), he would have been free to express himself by taking the pictures that he did. Condon, however, did not receive authorization, nor did he receive the consent of the families of those whose bodies he chose to photograph.137Id. at 703.

2. Control

When the government exerts custodial control over a person in life, this sometimes creates legal obligations that persist in death. The clearest example is the state’s duties to deceased prisoners.138See, e.g., Robyn Ross, Laid to Rest in Huntsville, Tex. Observer (Mar. 11, 2014, 11:34 AM), https://www.texasobserver.org/prison-inmates-laid-rest-huntsville [perma.cc/ERX2-MM2U]. These include informing family members of the death and providing a decent interment if the family is unable to do so. Under California law, for example, when a person dies in confinement and the family does not take possession of the body, the state “shall dispose of the body by cremation or burial.”139Cal. Penal Code § 5061 (West 2011). Arizona law is also illustrative. When a family is unwilling to provide for “the burial or other funeral and disposition arrangements, or cannot be located on reasonable inquiry,” the duty falls on the state.140Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 36-831 (Supp. 2020). This approach is common across the United States.141See, e.g., N.J. Admin. Code § 10A:16-7.5 (2021); N.Y. State Dep’t of Corr. & Cmty. Supervision, Directive No. 4013, Incarcerated Individual Deaths-Administrative Responsibility 7–9 (2020), https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2021/09/4013.pdf [perma.cc/9TYY-VLU9]; Va. Code Ann. § 32.1-309.2 (2018). Moreover, federal law provides for the “care and disposition of the remains of prisoners of war and interned enemy aliens who die while in . . . custody,” including by paying the expenses of notifying kin or providing for a burial.14210 U.S.C. § 1483.

3. Contract

Contracts also confer a significant degree of agency to act toward, or on behalf of, the dead. A particularly common example of this is health-care directives wherein individuals designate agents to control their interment in death.143See, e.g., Ala. Code § 34-13-11 (LexisNexis 2019); Ark. Code Ann. § 20-17-102(b)(1)(A) (2018); Del. Code tit. 12, § 262 (2021); Ind. Code § 30-5-5-16 (2020); Nev. Rev. Stat. § 451.024(1)(a) (2019); Or. Rev. Stat. § 97.130 (2019). Thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia have such statutes.144Marsh, supra note 31, at 47. For example, Indiana law allows a designated agent to “[m]ake plans for the disposition of the principal’s body, including executing a funeral planning declaration on behalf of the principal.”145Ind. Code § 30-5-5-16. Perhaps because it represents the will of the decedent, this authority supersedes others’ attempts to direct the disposition of the body, including that of family members.146See Ala. Code § 34-13-11.

Some obligations toward the dead arise by means of express and implied contracts to perform personal services, such as funeral services and burials.147Marsh, supra note 31, at 75. Those with a contractual obligation toward the decedent sometimes enforce that authority through litigation. In the Yome case, for example, when a widow attempted to disinter her husband, the religious order that opposed this attempt had signed a contract with the decedent.148Yome v. Gorman, 152 N.E. 126, 127–28 (N.Y. 1926); see supra notes 67–69 and accompanying text. Much more recently, in Alcor Life Extension Foundation v. Richardson,149785 N.W.2d 717, 730 (Iowa Ct. App. 2010). an Iowa court ordered, over a family’s objection, the disinterring of a body. The plaintiff was a company that had signed a contract with the decedent to cryogenically freeze his body.

With this authority to protect the decedent also comes legal obligations to do the same. Failure to use reasonable care when engaging in contractually obligated services can give rise to liability by way of tort or contract theories.150Allison E. Butler, Cause of Action Against Undertaker for the Mishandling of Human Remains, in 35 Causes of Action 2d 495, 533–34, § 17 (2007). Plaintiffs have relied on these theories to sue contractors for failing to properly transport a corpse, as well as negligently embalming or handling a body for burial.151See id. at 518–19. In Guth v. Freeland, for example, plaintiffs sued a mortuary for negligent infliction of emotional distress when, in violation of a written contract, the mortuary failed to refrigerate their parent’s body prior to an open-casket funeral.15228 P.3d 982 (Haw. 2001).

4. Community

In at least three respects, a person’s legal relationship to a decedent is also shaped by their shared community. First, local governments are legally tasked with providing decent burials for indigent and unclaimed individuals who die within their jurisdiction.153Mary Ann Barton, Undertakers of Last Resort: Indigent Burials on the Rise, Denting County Budgets, NACo (Dec. 10, 2018), https://www.naco.org/articles/undertakers-last-resort-indigent-burials-rise-denting-county-budgets [perma.cc/WK65-WT86]. Under New Hampshire law, for example, “[w]henever a person in any town is poor and unable to support himself, he shall be relieved and maintained by the overseers of public welfare of such town, whether or not he has residence there.”154N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 165:1 (2014); see also id. § 611-B:25 (Supp. 2020) (requiring that unclaimed bodies be “decently bur[ied] or cremate[d]” by the authority of local public officials). Georgia law similarly provides that when a decedent and “his or her family, and his or her immediate kindred are indigent and unable to provide for the decedent’s decent interment or cremation,” counties shall fund or reimburse the interment or cremation.155Ga. Code Ann. § 36-12-5 (2019).

Second, individuals have common social duties to avoid treating the dead in ways that would outrage communities or undermine public health. States outlaw mutilation, necrophilia, grave-robbing, grave desecration, and other conduct likely to outrage community sensibilities156See, e.g., Colo. Rev. Stat. § 18-9-113 (2020); Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 711-1107 (LexisNexis 2016); 18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 5509 (West 2015); W. Va. Code Ann. § 61-8-14 (LexisNexis 2020); Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2927.01(B) (LexisNexis 2019). or undermine the community’s physical health.157State v. Vestal, 611 S.W.2d 819, 823 (Tenn. 1981) (Drowota, J., dissenting). For example, when the State of Tennessee codified the common law crime of abandonment in 1858, the law initially read: “Any person who wilfully and unnecessarily, and in an improper manner, indecently exposes, throws away, or abandons any human body or the remains thereof, in any public place, or in any river, stream, pond, or other place, is guilty of a misdemeanor.”158Id. The state later upgraded this crime to a felony.159Id. In 1981, the Tennessee Supreme Court observed that the locations identified in this statute were places that either “offended the public’s sense of decency” or “exposed the public to the danger of contagious diseases or contamination of drinking water.”160Id. at 821 (majority opinion).

Third, with limited success, members of groups that have experienced violent subordination sometimes attempt to protect the interests of dead members of that group, relying on their shared tribal, ethnic, or cultural heritage. The most prominent example of this is the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), under which federally recognized Indian tribes may request that federal agencies, as well as institutions receiving federal funds, return culturally affiliated human remains.16128 U.S.C. §§ 3001–3013. NAGPRA is supplemented by the National Museum of the American Indian Act, which includes similar provisions applicable to Smithsonian museums.16220 U.S.C. §§ 80q to 80q-15.

C. Motive and Fault

When a living person or institution acts toward a dead person, motive and culpability also influence what conduct is deemed legally (and, likely, culturally) acceptable. At least four features of this phenomenon merit particular mention: remuneration, deception, mode of culpability, and forfeiture. That is, the law looks with particular suspicion upon exploiting dead persons for profit, deceptive acts, knowingly or recklessly harmful acts, and actions taken by a dead person’s killer.

1. Remuneration

“Don’t, for the sake of money, disturb the dead.”163Justin Wm. Moyer, ‘Hiding Real Black History’: Lawsuit Fights Plan to Move Historic Cemetery at MGM Casino’s Doorstep, Wash. Post (Apr. 6, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/hiding-real-black-history-lawsuit-fights-plan-to-move-historic-cemetery-at-mgm-casinos-doorstep/2017/04/03/18cbbf5e-10b4-11e7-8fed-dbb23e393b15_story.html [perma.cc/UVR3-V437]. Or so urged Michael Leventhal, the head of a preservation group based in Prince George’s County, Maryland, when MGM sought to disinter bodies from a colonial cemetery to build a new casino.164Id. Legal action by Black descendants of those buried in that cemetery proved unsuccessful.165Addison v. Peterson, No. 17-cv-00891 (D. Md. Dec. 15, 2017) (dismissing the case). But the principle expressed by Leventhal is often reflected in the law of the dead. When a living person attempts to profit on the back of a dead person’s body or image, this appears to significantly increase the likelihood that courts will deem the behavior unlawful. This observation especially holds when neither the decedent nor her family has authorized the exploitation.

In the 1949 case Baker v. State, for example, the State of Arkansas convicted an elderly man’s sole caregiver for indecently handling a corpse when, over the course of several days, she arranged his body in various positions so that passersby would think he was alive.166223 S.W.2d 809 (Ark. 1949). The caregiver then cashed his disability check when it arrived days after he died, keeping the proceeds for herself.167Baker, 223 S.W.2d at 811. These facts were sufficient to sustain a conviction and fine for indecently handling a dead body. The court analogized to a case from the English common law in which a court found that a jailor could be prosecuted for holding a deceased prisoner’s body and “refus[ing] to surrender it for proper burial until paid some claimed demand.”168Id. at 811–12 (citing R v. Fox (1842) 114 Eng. Rep. 95, 97 n.2; 2 QB Rep. 246, 248). The Baker court reasoned that “the jury could reasonably have concluded from the evidence that [the defendant] held the body . . . and had it placed in positions simulating life until she received the welfare check.”169Id. at 812.