Is There Anything Left in the Fight Against Partisan Gerrymandering? Congressional Redistricting Commissions and the “Independent State Legislature Theory”

Partisan gerrymandering is a scourge on our democracy. Instead of voters choosing their representatives, representatives choose their voters. Historically, individuals and states could pursue multiple paths to challenge partisan gerrymandering. One way was to bring claims in federal court. The Supreme Court shut this door in Rucho v. Common Cause. States can also resist partisan gerrymandering by establishing congressional redistricting commissions. However, the power of these commissions to draw congressional districts is at risk. In Moore v. Harper, a case decided in the Supreme Court’s 2022-2023 Term, the petitioners asked the Court to embrace the “Independent State Legislature Theory.” The ISLT, at a minimum, would allow federal review of state interpretations of state law governing congressional elections, including redistricting. Part I distills the Supreme Court’s opinions on redistricting commissions into two potential doctrinal routes: a more restrained version (ISLT-Lite) and a maximalist version (ISLT-Max). Part II proposes a framework to analyze existing congressional redistricting commissions for their constitutionality under each theory. Part III makes recommendations for building constitutionally sound congressional redistricting commissions under each theory, both for states with existing commissions and for those looking to reduce partisan gerrymandering in the future. While the future of ISLT, and congressional redistricting commissions more broadly, remains uncertain, this Note offers an analytical framework so states may continue to constitutionally alleviate partisan gerrymandering through the congressional redistricting commission framework.

Authors’ Note

This Note was originally meant to address the Court’s recent opinion in Moore v. Harper before it rendered its final decision.1Moore v. Harper, 600 U.S. 1 (2023). On June 27, 2023, the Court ruled 6-3 against the North Carolina House of Representatives, which had argued that the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause insulates from state judicial review the state legislature’s decisions regarding rules for federal elections. Legal scholars hold differing opinions on what exactly the opinion means for the idea commonly referred to as the “Independent State Legislature Theory” (ISLT). Some argue that Moore is a complete repudiation of the fringe theory that would have left state legislatures completely unaccountable to state courts and citizen initiatives.2See, e.g., Supreme Court Rejects Independent State Legislature Theory, Brennan Ctr. for Just. (June 27, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/supreme-court-rejects-independent-state-legislature-theory [perma.cc/FF6D-MWUP] (“The independent state legislature theory is now dead.”); Derek Muller, Moore v. Harper Vindicates Rehnquist’s Opinion in Bush v. Gore, Election L. Blog (June 27, 2023, 8:46 AM), https://electionlawblog.org/?p=137104 [perma.cc/2Z24-2TUY] (“The top line takeaway of Moore v. Harper is this: the Supreme Court has slammed the door shut on the argument that the state constitution or state judiciary cannot constrain the state legislature exercising power under the Elections Clause.”). Others argue that even if Moore rejected the most extreme version of the theory, the Court has left the door open for it to intervene should the justices determine that state court review violates the Elections Clause in a particular instance.3See, e.g., Richard H. Pildes, The Supreme Court Rejected a Dangerous Elections Theory. But It’s Not All Good News., N.Y. Times (June 28, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/28/opinion/supreme-court-independent-state-legislature-theory.html [perma.cc/N22U-354M] (“[T]he decision . . . is not a total rejection of the [ISL] theory.”); Rick Hasen, Breaking: Supreme Court Decides Moore v. Harper, Rejecting Maximalist Version of Independent State Legislature Theory but Giving Federal Courts a Chance to Second Guess Some State Rulings as “Transgressing the Ordinary Bounds of Judicial Review,” Election L. Blog (June 27, 2023, 7:18 AM), https://electionlawblog.org/?p=137093 [perma.cc/C3NE-GGZV] (“The United States Supreme Court, on a 6-3 vote, has adopted a compromise position on the meaning of the independent state legislature theory.”). Indeed, even after Moore, state legislators continue to push the ISLT to challenge commonsense election laws in states like Michigan before the 2024 elections.4Marc Elias, A Dangerous Legal Theory Returns for 2024, Democracy Docket (Oct. 24, 2023), https://www.democracydocket.com/opinion/a-dangerous-legal-theory-returns-for-2024 [perma.cc/D5QE-8MAX]. If the door to invoking the theory truly remains open, as it seems to be, it is crucial to foresee the possible versions of ISLT and the catastrophic impact its adoption could have on the country. This piece provides insight into 1) what a “lighter” version of the theory would look like should the Court ever articulate what the “ordinary bounds of judicial review” are,5Moore, 600 U.S. at 36. and 2) the impact such a minimalist theory, as well as the temporarily rejected maximalist theory, would have on the landscape of congressional redistricting commissions. Discourse around ISLT and its potential ramifications should only deepen in light of Moore. We hope that this piece helps contribute to that burgeoning scholarship.

Introduction

On June 27, 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States issued its ruling in Moore v. Harper, a case that could have untethered state legislatures from checks by any other state authorities when setting their voting procedures for federal elections.6Id. The Court refused to go that far, but also noted that state courts did not have “free rein” to check their legislatures on matters of state law.7Id. at 34. This Note explores the uncertain landscape of congressional redistricting commissions after Moore.8Some states have redistricting commissions with only the authority to draw state legislative district lines. See, e.g., Doug Spencer, Illinois: State Summary, Loy. L. Sch., https://redistricting.lls.edu/state/illinois/?cycle=2020&level=Congress&startdate=2021-11-23 [perma.cc/7JNM-PVV9] (Illinois). Some states have redistricting commissions with only the authority to draw congressional district lines. See, e.g., Doug Spencer, New Jersey: State Summary, Loy. L. Sch., https://redistricting.lls.edu/state/new-jersey/?cycle=2020&level=Congress&startdate=2021-12-22 [perma.cc/T6GW-EKKH] (New Jersey). Some states have redistricting commissions with the authority to draw both congressional and state legislative district lines. See, e.g., Citizens Redistricting Commission, Common Cause, https://www.commoncause.org/california/our-work/ensure-fair-districts-reflective-democracy/california-redistricting-commission [perma.cc/HA8Y-DNJN] (California). We use the term “congressional redistricting commission” to refer to all redistricting commissions that have some authority to draw congressional district lines (i.e. those in the second and third categories). There are four specific subcategories of redistricting commissions within the more general term “redistricting commission,” regardless of whether those commissions draw the lines for only congressional districts, state districts, or both. Those four types include: independent, advisory, backup, and politician commissions. See generally Bruce E. Cain, Redistricting Commissions: A Better Political Buffer?, 121 Yale L.J. 1808 (2012). To the extent that we use these more specific terms, rather than the all-encompassing “congressional redistricting commission,” we use them as terms of art based on Cain’s description. Historically, in all states with two or more congressional districts, state legislatures drew districts for both state and federal elections.9Boundary Delimitation, ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, https://aceproject.org/ace-en/topics/bd/annex/bdy/bdy_us [perma.cc/4ZF3-H6QL]. This partisan redistricting practice created perverse incentives for politicians—dominant-party legislators focused not on elevating the voice of the people but instead on entrenching their own power.10Nathan S. Catanese, Note, Gerrymandered Gridlock: Assessing the Hazardous Impact of Partisan Redistricting, 28 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol’y 323, 327–31 (2014). However, in a trend reaching back to the 1960s that has been picking up steam in the last decade, legislatures, constitutional delegations, and individuals across the nation have been fighting back against “partisan gerrymandering” by adopting alternative approaches to redistricting.11Connecticut created the first congressional redistricting commission in the United States in 1965. Sandra Norman-Eady & Kristin Sullivan, Conn. Off. of Legis. Rsch., 1965 Constitutional Convention, 2008-R-0456 (2008). In 1966, New Jersey followed suit with the first redistricting commission for state legislative districts. Mark J. Magyar, Redistricting Reform in New Jersey 1 (2011/2012), https://www.njslom.org/DocumentCenter/View/6540/Redistricting-Reform-in-New-Jersey [perma.cc/ZJB2-KSA2]. Hawaiʻi created its commission in 1968. Hawaii Provisions for Future Reapportionment, Amendment 2 (1968), Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Hawaii_Provisions_for_Future_Reapportionment,_Amendment_2_(1968) [perma.cc/C436-8QN2].

Partisan gerrymandering occurs when the majority party in a state legislature draws electoral districts to disproportionately benefit itself at the expense of minority parties, regardless of the partisan breakdown of voters statewide.12Ariz. State Legislature v. Ariz. Indep. Redistricting Comm’n, 576 U.S. 787, 791 (2015) (“[T]he problem of partisan gerrymandering [is] the drawing of legislative district lines to subordinate adherents of one political party and entrench a rival party in power.”); Alex Tausanovitch & Danielle Root, How Partisan Gerrymandering Limits Voting Rights, Ctr. for Am. Progress (July 8, 2020), https://www.americanprogress.org/article/partisan-gerrymandering-limits-voting-rights [perma.cc/H6FC-3AWU]. Scholars and courts alike view partisan gerrymandering as dangerous to democracy, particularly due to its interference with the ability of the people to fully exercise their will over their elected representatives.13Ariz. State Legislature, 576 U.S. at 791 (“Partisan gerrymanders are incompatible with democratic principles.” (cleaned up) (quoting Vieth v. Jubelirer, 541 U.S. 267, 292 (2004) (plurality opinion))); see Vieth, 541 U.S. at 316 (Kennedy, J., concurring in judgment) (noting that the “ordered working of our Republic, and of the democratic process, depends on a sense of decorum and restraint in all branches of government,” which was “abandoned” by an extreme partisan gerrymander in Pennsylvania); Rucho v. Common Cause, 139 S. Ct. 2484, 2509 (2019) (Kagan, J., dissenting) (“The partisan gerrymanders in these cases deprived citizens of the most fundamental of their constitutional rights: the rights to participate equally in the political process, to join with others to advance political beliefs, and to choose their political representatives. In so doing, the partisan gerrymanders here debased and dishonored our democracy, turning upside-down the core American idea that all governmental power derives from the people.”); Harper v. Hall, 868 S.E.2d 499, 542 (N.C. 2022) (holding partisan gerrymandering can violate the North Carolina Constitution because it “prevent[s] elections from reflecting the will of the people impartially and by diminishing or diluting voting power on the basis of partisan affiliation” and “prevents election outcomes from reflecting the will of the people”); Catanese, supra note 10, at 350–51 (noting partisan gerrymandering causes gridlock problems, negatively impacts voter turnout, and increases voter apathy); Kevin Wender, Note, The “Whip Hand”: Congress’s Elections Clause Power as the Last Hope for Redistricting Reform After Rucho, 88 Fordham L. Rev. 2085, 2088 (2020) (“[P]artisan gerrymanders have had a corrosive effect on American democracy by decreasing competitive elections, entrenching partisan power in a way that is unrepresentative of the electorate, and diluting the franchise of a large number of voters solely because of their party affiliation.”); Samuel S.-H. Wang, Three Tests for Practical Evaluation of Partisan Gerrymandering, 68 Stan. L. Rev. 1263, 1272 (2016) (“Partisan gerrymandering can also chill a voter’s freedom to choose between political parties. In gerrymandered districts, the noncompetitive nature of the general election leaves the primary election as the only avenue for voters to affect their representation. Such a situation creates a powerful incentive to compel voters to join the dominant political party . . . .”). For decades, there were three primary avenues to resist partisan gerrymandering: individuals could sue in federal14See, e.g., Vieth, 541 U.S. 267. or state court15See, e.g., Harper, 868 S.E.2d 499. or states (either through their citizens or legislatures) could create alternative redistricting options—typically in the form of commissions—so that legislatures would no longer wield the sole power to draw the maps.16See supra note 8 and accompanying text.

In Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court held that partisan gerrymandering is a nonjusticiable political question,17Rucho, 139 S. Ct. at 2485. closing federal court doors to all plaintiffs hoping to pursue a partisan gerrymandering claim. This left two primary options to alleviate the problem: bring state-level cases or advocate for redistricting commissions.18See id. at 2507 (“States are restricting partisan considerations in districting through legislation. One way they are doing so is by placing power to draw electoral districts in the hands of independent commissions.”); id. at 2508 (“We express no view on any of these pending proposals [to form redistricting commissions].”). While Congress also retains power to reform the congressional redistricting process under Article I, Section 4 of the Constitution, it has taken a “historically limited role” in doing so and has not passed legislation in this area in recent memory. Sarah J. Eckman, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R45951, Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives 1, 17 (2021). Congress has attempted to require states to establish “independent redistricting commission[s]” to develop and enact “any congressional redistricting” plan for the state. For the People Act of 2021, H.R. 1, 117th Cong. § 2401(a) (2021) (reintroduced after failing to pass in 2019). After passing along party lines (all Democrats voting for; all Republicans against) in the House, a Republican-led filibuster in the Senate killed the bill. Barbara Sprunt, Senate Republicans Block Democrats’ Sweeping Voting Rights Legislation, NPR (June 22, 2021, 8:22 PM), https://www.npr.org/2021/06/22/1008737806/democrats-sweeping-voting-rights-legislation-is-headed-for-failure-in-the-senate [perma.cc/JRB8-3PV4]. While the Court did not remove the state court option completely in Moore, the opinion instills further uncertainty over the constitutionality of congressional redistricting by commissions.

In Moore v. Harper, the Court heard a challenge to the North Carolina Supreme Court’s ruling that struck down the state legislature’s redistricting maps as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander under the state constitution.19Moore v. Harper, 600 U.S. 1 (2023); Harper, 868 S.E.2d at 542, 555 (holding that 1) partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable under the North Carolina Constitution’s “fundamental right to vote on equal terms” clause, and that 2) at least one of the state legislature’s maps fails strict scrutiny). The Supreme Court decided that the U.S. Constitution does not completely prohibit state courts from interpreting state law regulating federal elections,20See Moore v. Harper, SCOTUSblog, https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/moore-v-harper-2 [perma.cc/3WD7-SLT8]. thereby declining to adopt what has become known as the “Independent State Legislature Theory.” The ISLT posits that the U.S. Constitution—in explicitly delegating authority to set voting procedures for federal elections within Article 1, Section 4 (the Elections Clause) and Article 2, Section 1 (the Electors Clause)21Moore does not directly implicate the “Electors Clause”; however, the Court read the term “Legislature” identically for both clauses. Moore, 600 U.S. at 25–28. to each state via the “Legislature thereof” language22 U.S. Const. art. I, § 4, cl. 1 (“The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations . . . .”); Id. art. II, § 1, cl. 3 (“Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress . . . .”).—refers exclusively to the state legislature and excludes other state actors, including state courts conducting judicial review.23See Michael T. Morley, The Independent State Legislature Doctrine, 90 Fordham L. Rev. 501, 502–03, 15 (2021). At a minimum, adopting ISLT would insulate state laws governing federal elections from challenges based on state laws and constitutions. Without federal courts as an alternative, removing these claims from the grasp of state courts would have left individuals with no judicial recourse for partisan gerrymandering. This would have, in turn, left redistricting commissions as virtually the only weapon left against state legislatures egregiously gerrymandering their maps for partisan gain. The Court’s decision in Moore leaves the power of commissions to draw maps for federal congressional elections intact, for now. The Court, however, left open a door for future challenges to these institutions.24Moore, 600 U.S. at 34 (“[T]he Elections Clause expressly vests power to carry out its provisions in ‘the Legislature’ of each State, a deliberate choice that this Court must respect.”). No version of ISLT would affect these commissions’ ability to redistrict state district lines. See, e.g., Leah M. Litman & Katherine Shaw, Textualism, Judicial Supremacy, and the Independent State Legislature Theory, 2022 Wis. L. Rev. 1235. If the Court decides later to walk through that door, it seems inevitable that the Court would “condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void.”25Rucho v. Common Cause, 139 S. Ct. 2484, 2507 (2019).

So, where does the decision in Moore leave us? Will commissions remain a viable means to fight partisan gerrymandering in federal elections, or must we all accept partisan gerrymandering as an inevitable scourge on democracy? Must we live with shouting into the void?

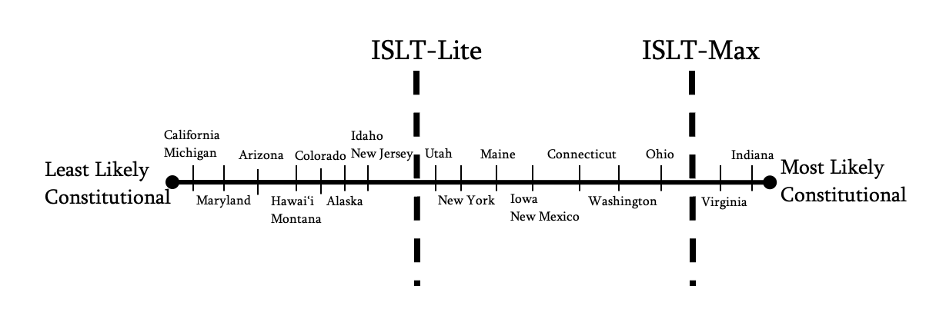

There is plenty of scholarship on ISLT’s history and merits (or lack thereof).26See generally A Guide to Recent Scholarship on the ‘Independent State Legislature Theory,’ Brennan Ctr. for Just. (Oct. 14, 2022), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/guide-recent-scholarship-independent-state-legislature-theory [perma.cc/CQ9A-MY3P] (collecting scholarship). We will not fully rehash it here.27For a discussion of the doctrine, see infra Part I. Instead, this Note examines two potential versions of ISLT that the Supreme Court could still adopt after Moore and analyzes the possible impacts of each on the viability of redistricting commissions.28We predict that the likely effect of ISLT will not vary from state to state for state supreme courts as it might for redistricting commissions. Part I lays out two possible versions of ISLT that the Court could adopt: “ISLT-Max”29The Court seemed to disavow the full-throated maximalist theory defended by Justices Thomas and Gorsuch in dissent. Moore, 600 U.S. at 25–30. and “ISLT-Lite.”30Carolyn Shapiro refers to a “maximalist-ISLT.” Although there are some similarities with how her piece describes “maximalist-ISLT” and how this piece will describe “ISLT-Max,” they are distinct. Professor Shapiro’s maximalist-ISLT instead would compel federal court review of state court interpretations of election law. Carolyn Shapiro, The Independent State Legislature Theory, Federal Courts, and State Law, 90 U. Chi. L. Rev. 137, 142–43 (2023). Part II applies both theories to every existing congressional redistricting commission and attempts to predict how each will fare constitutionally under both theories. Finally, Part III provides recommendations to states on how to best prepare for a potential ISLT world.

I. ISLT-Max or ISLT-Lite?

The first time an ISL-like theory appeared in modern Supreme Court opinions was in Bush v. Palm Beach County Canvassing Board,31See Bush v. Palm Beach Cnty. Canvassing Bd., 531 U.S. 70 (2000) (per curiam). the prequel to Bush v. Gore.32Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000) (per curiam). In Palm Beach County, the Court hinted at a theory that would untether state legislatures from state oversight when they pass laws governing presidential elections,33Palm Beach Cnty., 531 U.S. at 76 (“As a general rule, this Court defers to a state court’s interpretation of a state statute. But in the case of a law enacted by a state legislature applicable not only to elections to state offices, but also to the selection of Presidential electors, the legislature is not acting solely under the authority given it by the people of the State, but by virtue of a direct grant of authority made under Art. II, § 1, cl. 2, of the United States Constitution.”). The Court references an older case it deemed relevant to this theory: McPherson v. Blacker, 146 U.S. 1 (1892). In dicta, McPherson seems to reference a maximalist form of ISLT. See id. at 25. However, that case concerned whether a state law violated the federal Constitution directly, which would not implicate the modern ISLT, as the Court admitted in Palm Beach County, 531 U.S. at 76 (“[W]e did not address the same question petitioner raises here [in McPherson] . . . .”). Likewise, the Court in Moore dismissed the relevance of McPherson in this context. Moore, 600 U.S. at 27–28. but it ultimately punted this question and sent the case back down to the lower courts.34Palm Beach Cnty., 531 U.S. at 78 (“The judgment of the Supreme Court of Florida is therefore vacated, and the case is remanded for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.”). That same Term, the Court settled the 2000 Presidential Election issues in Gore,35Gore, 531 U.S. at 110. where the ISLT entered center stage of the legal debate for the first time.36Id. at 98, 112 (Rehnquist, C.J., concurring).

In his Gore concurrence, Chief Justice Rehnquist posited that “a few exceptional cases in which the Constitution imposes a duty or confers a power on a particular branch of a State’s government” may exist and that Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 is one of them.37Id. at 112. That provision states that “[e]ach State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct,” electors for President and Vice President.38U.S. Const. art. II, § 1, cl. 2. Thus, the legislature’s election laws gain “independent significance” subject to review by federal courts, notwithstanding preexisting state court interpretation.39Gore, 531 U.S. at 112–13 (Rehnquist, C.J., concurring). This theory—that federal courts can intervene to interpret state election laws concerning federal elections despite state court decisions regarding the same, and thereby protect state legislature independence, became known as the Independent State Legislature Theory.

Even at these early stages, the theory faced stark criticism. There were four separate dissents in Gore, each condemning ISLT.40Id. at 123 (Stevens, J., dissenting) (“[Article II] does not create state legislatures out of whole cloth, but rather takes them as they come—as creatures born of, and constrained by, their state constitutions.”); id. at 131 (Souter, J., dissenting) (“But the [Florida Supreme Court] majority view is in each instance within the bounds of reasonable interpretation, and the law as declared is consistent with Article II.”); id. at 141 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting) (“By holding that Article II requires our revision of a state court’s construction of state laws in order to protect one organ of the State from another, THE CHIEF JUSTICE contradicts the basic principle that a State may organize itself as it sees fit.”); id. at 148 (Breyer, J., dissenting) (“But neither the text of Article II itself nor the only case the concurrence cites that interprets Article II . . . grants unlimited power to the legislature, devoid of any state constitutional limitations, to select the manner of appointing electors.”). For years, ISLT rarely reared its head. But recently it has made judicial appearances with increasing frequency. Each time ISLT does so, it seems to take on a slightly different iteration. This makes it difficult to predict exactly how far the Court may stretch the theory (should it choose to expand upon it at all) with the wiggle room it left itself in Moore. Ultimately, though, the Court has hinted at and coalesced around two main forms of ISLT in its jurisprudence, including in Moore: a more restrained theory and a maximalist theory.

In Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, Chief Justice Roberts’s dissent put forth the more restrained approach. He accepted the basic ISLT premise that the term “Legislature” in the federal Constitution means the “representative [state] body.”41Ariz. State Legislature v. Ariz Indep. Redistricting Comm’n, 576 U.S. 787, 841 (2015) (Roberts, C.J., dissenting) (“The constitutional text, structure, history, and precedent establish a straightforward rule: Under the Elections Clause, ‘the Legislature’ is a representative body . . . .”). The chief justice clarified that “the state legislature need not be exclusive in congressional districting, but neither may it be excluded.”42Id. at 841–42. He went on to note that “reading the Elections Clause to require the involvement of the legislature will not affect most other redistricting commissions . . . . [M]any States have commissions that play an ‘auxiliary role’ in congressional redistricting. But in these States, unlike in Arizona, the legislature retains primary authority over congressional redistricting.”43Id. at 847–48 (citation omitted). By putting forth this version of ISLT—what we term “ISLT-Lite”—the chief justice suggested he may be willing to let some redistricting alternatives survive constitutional scrutiny, so long as they do not “displace” the legislature and act only in an “auxiliary role.”44Id. Note that this is consistent with Chief Justice Rehnquist’s concurrence in Gore, 531 U.S. at 113–14 (Rehnquist, C.J., concurring) (approving the legislature’s ability to “delegate[] the authority to run the elections and to oversee election disputes to the Secretary of State . . . and to state circuit courts” (citation omitted)). Justices Alito, Scalia, and Thomas signed on to the chief justice’s opinion.45Justice Thomas wrote a separate dissent but did not discuss ISLT. Ariz. State Legislature, 576 U.S. at 859 (Thomas, J., dissenting). The majority did not adopt Chief Justice Roberts’s view and instead rejected the theory outright.

Justice Ginsburg’s majority opinion in Arizona State Legislature rejected the narrow interpretation of the word “legislature” that proponents of ISLT support and instead opted for a more capacious understanding—one that depends on the kind of function the legislature looks to exercise46Id. at 808 (majority opinion) (“Constantly resisted by THE CHIEF JUSTICE, but well understood in opinions that speak for the Court: ‘[T]he meaning of the word “legislature,” used several times in the Federal Constitution, differs according to the connection in which it is employed, depend[ent] upon the character of the function which that body in each instance is called upon to exercise.’ ” (alterations in original) (quoting Atl. Cleaners & Dyers, Inc. v. United States, 286 U.S. 427, 434 (1932))). (consistent with Justice Stevens’s dissent in Gore).47Gore, 531 U.S. at 123 n.1 (Stevens, J., dissenting) (“Wherever the term ‘legislature’ is used in the Constitution it is necessary to consider the nature of the particular action in view.” (quoting Smiley v. Holm, 285 U.S. 355, 366 (1932))). The Court held congressional redistricting was a lawmaking function,48Ariz. State Legislature, 576 U.S. at 808 (“In sum, our precedent teaches that redistricting is a legislative function, to be performed in accordance with the State’s prescriptions for lawmaking . . . .”). then defined “legislature” not strictly as the representative body but instead as any entity exercising the lawmaking power.49Id. at 813–14. To support its position, the Court relied on founding-era dictionary definitions,50Id. (collecting dictionaries). the purpose of the Elections Clause,51Id. at 816 (“The Elections Clause, however, is not reasonably read to disarm States from adopting modes of legislation that place the lead rein in the people’s hands.”). principles of sovereignty,52Id. at 817 (“Through the structure of its government, and the character of those who exercise government authority, a State defines itself as a sovereign.” (quoting Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452, 460 (1991))). and the truism that governmental power is ultimately derived from the people.53Id. at 819 (“The genius of republican liberty seems to demand . . . that all power should be derived from the people . . . .” (quoting The Federalist No. 37, at 227 (James Madison) (Clinton Rossiter ed., 1961))). The Court emphasized that this reading of “legislature” is especially necessary in the context of redistricting.54Id. at 820 (“In this light, it would be perverse to interpret the term ‘Legislature’ in the Elections Clause so as to exclude lawmaking by the people, particularly where such lawmaking is intended to check legislators’ ability to choose the district lines they run in . . . .”). The Arizona Constitution equally vests lawmaking power in both the people and the state legislature: the people via ballot initiative, and the legislature via statute.55Id. at 814 (“As to the ‘power that makes laws’ in Arizona, initiatives adopted by the voters legislate for the State just as measures passed by the representative body do.” (citing Ariz. Const. art. IV, pt. 1, § 1 (“The legislative authority of the state shall be vested in the legislature, consisting of a senate and a house of representatives, but the people reserve the power to propose laws and amendments to the constitution and to enact or reject such laws and amendments at the polls, independently of the legislature . . . .”))); Cave Creek Unified Sch. Dist. v. Ducey, 308 P.3d 1152, 1155 (Ariz. 2013) (“The legislature and ‘electorate share lawmaking power under Arizona’s system of government.’ ” (quoting Ariz. Early Childhood Dev. & Health Bd. v. Brewer, 212 P.3d 805, 807 (Ariz. 2009))). So, the Court held that “the people may delegate [by ballot initiative] their legislative authority over redistricting to an independent commission just as the representative body may choose to do.”56Ariz. State Legislature, 576 U.S. at 814. Based on her questioning during oral argument in Moore, Justice Jackson seems to share Justice Ginsburg’s view. See, e.g., Transcript of Oral Argument at 13, Moore v. Harper, 600 U.S. 1 (2023) (No. 21-1271) [hereinafter Moore Transcript] (“In other words, if the state constitution tells us what the state legislature is and what it can do and who gets on it and what the scope of legislative authority is, then, when the state supreme court is reviewing the actions of an entity that calls itself the legislature, why isn’t it just looking to the state constitution and doing exactly the kind of thing you say . . . when you admitted that this is really about what authority the legislature has? In other words, the authority comes from the state constitution, doesn’t it?”). This ruling was groundbreaking for the redistricting cause, affirming that voters across the United States could constitutionally exclude their state representatives from drawing electoral maps and instead vest that power in independent congressional redistricting commissions.

The Supreme Court looks much different today than it did in 2015,57Three of the justices who joined the Arizona State Legislature majority opinion to reject ISLT have since retired or died, namely Justices Ginsburg, Kennedy, and Breyer. Justices Barrett, Kavanaugh, and Jackson, respectively, replaced those justices. Only one of the dissenting justices in the case—Justice Scalia—is no longer on the Court. Justice Gorsuch—the prime proponent of what we term the “ISLT-Max” infra—took Justice Scalia’s seat on the bench. See Justices 1789 to Present, Sup. Ct. of the U.S., https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/members_text.aspx [perma.cc/77AZ-CFFY]. and while the majority in Moore did cite to Arizona State Legislature favorably at times,58Moore, 600 U.S. at 25–26, 30–31. it remains unclear what those views mean for ISLT in the congressional redistricting process.59While the Court in Moore did rely on the Court’s majority opinion in Arizona State Legislature, the Court in Moore was careful to not directly uphold the contention that such independent redistricting commissions are constitutional. Instead, the Court in Moore bypassed such a chance to do so and instead merely commented (after a brief analysis) that the “significant point for present purposes is that the Court in Arizona State Legislature recognized that whatever authority was responsible for redistricting, that entity remained subject to constraints set forth in the State Constitution.” Id. at 25 (referencing Ariz. State Legislature, 576 U.S. at 816–17). Just four years after Arizona State Legislature, Chief Justice Roberts seemed to double down on the ISLT-Lite he espoused in his Arizona dissent. In Rucho v. Common Cause, without deciding on the merits of ISLT, he pointed to the existence of independent commissions and a “state demographer” as possible ways for states to tackle partisan gerrymandering.60Rucho v. Common Cause, 139 S. Ct. 2484, 2507 (2019) (“Indeed, numerous other States are restricting partisan considerations in districting through legislation. One way they are doing so is by placing power to draw electoral districts in the hands of independent commissions.”). Further, in his concurrence in Democratic National Committee v. Wisconsin State Legislature, Chief Justice Roberts affirmed “the authority of state courts to apply their own constitutions to election regulations.”61Democratic Nat’l Comm. v. Wis. State Legislature, 141 S. Ct. 28, 28 (2020) (mem.) (Roberts, C.J., concurring in the denial of application to vacate stay). Likewise, in his majority opinion in Moore, he noted that the term “Legislature” in the Elections Clause does not necessarily “preclude a State from vesting congressional redistricting authority in a body other than the elected group of officials who ordinarily exercise lawmaking power.”62Moore, 600 U.S. at 25. In all three instances, the chief justice likely viewed the role of these nonlegislative actors as consistent with ISLT-Lite because the commission still only retains an “auxiliary role” in congressional redistricting.63See supra note 43 and accompanying text. Other justices began departing from the chief in significant respects at this point in his writing—most prominent among them being Justice Gorsuch.

Justice Gorsuch wrote a separate concurrence in Democratic National Committee, joined by Justice Kavanaugh, making clear he disagreed with the extent to which the chief justice limited ISLT. Justice Gorsuch posited that the “Constitution provides that state legislatures—not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials—bear primary responsibility for setting election rules.”64Democratic Nat’l Comm., 141 S. Ct. at 29 (Gorsuch, J., concurring in the denial of application to vacate stay). Based on how Justice Gorsuch uses the word “primary,” we take it to mean “of first rank, importance, or value.”65Primary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/primary [perma.cc/DTW2-PTYV]. Justice Gorsuch thus presented the more expansive version of the theory: “ISLT-Max.” To survive ISLT-Max, the state legislature must play a “primary” role, or one “of first rank, importance, or value,” in each step of the redistricting process. While both Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Gorsuch use the word “primary” to describe the legislature’s necessary role to survive their theories, the chief justice’s ISLT-Lite rests more on functional concerns about commissions displacing legislative power, whereas Justice Gorsuch’s ISLT-Max depends on formalist concerns about other nonlegislative state officials, rather than the legislature (as a body of legislators), wielding primary power over congressional redistricting. Therefore, for example, the chief justice’s theory readily incorporates a governor’s veto in the plan enactment process as standard-issue legislating might, but such a gubernatorial role under Justice Gorsuch’s theory would render the scheme unconstitutional. It remains uncertain if Moore marks a meaningful departure from the chief justice’s ISLT-Lite views in these prior opinions as the majority opinion does not expound the theory and since it left the door open for future challenges.66Moore, 600 U.S. at 34–36.

While Justices Thomas and Alito embrace some form of ISLT, it is unclear how far they would agree to take it. Neither wrote separately nor joined either Chief Justice Roberts’s or Justice Gorsuch’s opinions in Democratic National Committee.67See Democratic Nat’l Comm., 141 S. Ct. 28. Justices Thomas and Gorsuch did, however, join Justice Alito’s statement in Republican Party of Pennsylvania v. Boockvar, which refused to go as far as ISLT-Max.68See Republican Party of Pa. v. Boockvar, 141 S. Ct. 1, 1–2 (2020) (Alito, J., denying motion for expedited review) (“The provisions of the Federal Constitution conferring on state legislatures, not state courts, the authority to make rules governing federal elections would be meaningless if a state court could override the rules adopted by the legislature simply by claiming that a state constitutional provision gave the courts the authority to make whatever rules it thought appropriate for the conduct of a fair election.”). Justice Thomas wrote a dissent in another case where he made it clear that his problem is with “nonlegislative officials” making election law decisions.69Republican Party of Pa. v. Degraffenreid, 141 S. Ct. 732, 732 (2021) (mem.) (Thomas, J., dissenting from the denial of certiorari) (“The Constitution gives to each state legislature authority to determine the ‘Manner’ of federal elections. Yet both before and after the 2020 election, nonlegislative officials in various States took it upon themselves to set the rules instead.” (citations omitted)). But see Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98, 112 (2000) (Rehnquist, C.J., concurring) (where Justice Thomas joined Chief Justice Rehnquist’s concurrence, which did not make such a distinction). He did not elaborate on what he meant by “nonlegislative officials.” However, he seemed to abandon this potentially middle-ground approach in his Moore dissent. While dissenting on the merits, Justice Thomas formally differentiated between power wielded by the state, which “in the ordinary sense of the Constitution, is a political community of free citizens . . . organized under a government sanctioned and limited by a written constitution,”70Moore, 600 U.S. at 57 (Thomas, J., dissenting) (quoting Texas v. White, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 700, 721 (1869)). compared to that of the power wielded by the legislature, which “generally means ‘the representative body which makes the laws of the people.’ ”71Id. (quoting Smiley v. Holm, 285 U.S. 355, 365 (1932) (internal alterations and quotation marks omitted)). He went on to state that the Elections Clause’s function is a lawmaking one, and that courts look to “a State’s written constitution to determine the constitutional actors in whom lawmaking power is vested.”72Id. To Justice Thomas, the term “Legislature thereof” in Article I means “ ‘the lawmaking body or power of the state, as established by the state Constitution,’ or . . . ‘that body of persons within a state clothed with authority to make the laws.’ ”73Id. at 58 (quoting State ex rel. Schrader v. Polley, 127 N.W. 848, 850–51 (S.D. 1910)). By taking this approach in Moore, it seems as though Justice Thomas may more firmly ascribe to the ISLT-Max camp along with Justice Gorsuch.

Justice Gorsuch joined Justice Thomas’s dissent in full, whereas Justice Alito did not join the merits portion of the dissent.74Id. at 40. As such, Justice Alito seems torn on the theory. He dissented from a denial of emergency relief to the defendants in Moore v. Harper, noting “there must be some limit on the authority of state courts to countermand actions taken by state legislatures when they are prescribing rules for the conduct of federal elections,” implying the federal Constitution is not a complete limitation.75Moore v. Harper, 142 S. Ct. 1089, 1091 (2022) (Alito, J., dissenting from denial of application for stay). However, he also said,

This Clause could have said that these rules are to be prescribed “by each State,” which would have left it up to each State to decide which branch, component, or officer of the state government should exercise that power. . . . [But] [i]ts language specifies a particular organ of a state government, and we must take that language seriously.76Id. at 1090.

Given that he implies there is not a complete limit on state court authority, Justice Alito may support ISLT-Lite rather than ISLT-Max.77See also Moore Transcript, supra note 56, at 39 (where Justice Alito asks Petitioner’s counsel: “[E]ven under your primary theory, however, isn’t it inevitable that the state courts are going to have to interpret [election] provisions and isn’t it inevitable that state election officials in the Executive Branch are going to have to make decisions about all sorts of little things that come up concerning the conduct of elections?”); Mac Brower, Four Takeaways: Moore v. Harper Oral Argument, Democracy Docket (Dec. 8, 2022), https://www.democracydocket.com/analysis/four-takeaways-moore-v-harper-oral-argument [perma.cc/AWH6-ETXM] (“Alito and Kavanaugh, two of the most conservative justices when it comes to voting, were not buying the Moore position.”). But see Michael Sozan, Supreme Court Oral Arguments in Moore v. Harper Discredit Election Theory That Could Undermine Democracy, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Dec. 7, 2022), https://www.americanprogress.org/article/supreme-court-oral-arguments-in-moore-v-harper-discredit-election-theory-that-could-undermine-democracy [perma.cc/9P67-KTCM] (“Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch seemed the most open to accepting an aggressive form of the ISL theory.”). Notably, Justice Alito was the only justice to not join any ISLT merits portion of the majority, concurring, or dissenting opinions in Moore, opting to instead only sign on to Justice Thomas’s discussion of how the case should have been rendered moot. Moore, 600 U.S. at 40.

Ultimately, Chief Justice Roberts and the three more liberal justices refused to endorse ISLT-Max in Moore, in line with their prior views on the matter.78Justices Sotomayor and Kagan joined the majority in Arizona State Legislature to uphold the Commission’s constitutionality. Ariz. State Legislature v. Ariz. Indep. Redistricting Comm’n, 576 U.S. 787 (2015). Justice Jackson’s questions at the Moore oral argument foreshadowed her agreement with her liberal-leaning peer justices on the meaning of “legislature,” suggesting she would vote against ISLT-Max. See Moore Transcript, supra note 56, at 174. Surprising some, these four found unlikely bedfellows in Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh. Justice Barrett had not previously opined on the theory before Moore’s decision, but her questioning at oral argument suggested she would vote against a full-throated ISLT-Max.79See Moore Transcript, supra note 56, at 20, 63–64 (showing Justice Barrett questioning ISLT’s underlying logic: “If [the Elections Clause] did not appear in the Constitution, would the baseline assumption have been that the states possess the power to regulate elections for federal office anyway? Because, if so, I don’t see how it’s a delegation as[ ]opposed to a clause that clips state authority perhaps by saying it must be exercised by the legislature and by giving Congress the power of override”; and “we know from [Ohio ex rel. Davis v.] Hildebran[t, 241 U.S. 565 (1916)] that if a districting is done by referendum, that’s okay, you know, that doesn’t violate the Elections Clause. . . . When [a state constitution] can be changed by a simple majority, why is that more entrenchment [than a state statute] and why would we say that having it appear in the Constitution is problematic when, if it appeared through the referendum process and the legislative process, it’s not?”). Justice Kavanaugh seemed to support ISLT-Max before his time on the bench.80Justice Kavanaugh advocated for such a maximalist view in the Electors Clause context during the controversy surrounding the 2000 Presidential Election. See CNN, Brett Kavanaugh Talks About Bush v. Gore (December 2000), YouTube, at 0:52–0:56 (Oct. 13, 2018), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R28YOTZt-vs (“[Article II] delegates authority directly to the state legislatures.”). These two signing onto the majority opinion inspires hope that any future ISLT case that could threaten congressional redistricting commissions would at least not result in the most dangerous, ISLT-Max, approach. However, Justice Kavanaugh invited others to make persuasive arguments on this point in his sole concurrence in Moore, leaving a question mark in his voting column for potential future cases.81Moore, 600 U.S. at 39–40 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

We know Justice Gorsuch supports ISLT-Max. Justice Alito seems to fall to the ideological right of the chief justice in saying state courts lack a role in congressional redistricting. However, he has not signed onto Justice Gorsuch’s ISLT-Max articulation. He seems more aligned with Justice Thomas’s middle-ground, nonlegislative-officials view, but that view seems abandoned now even by Justice Thomas in his Moore dissent where he endorsed the more radical ISLT-Max theory.82Id. at 57–58 (Thomas, J., dissenting).

Regardless of which iteration of ISLT may take hold in a future case post-Moore, historical legislative practice shows that there is a spectrum of legislative involvement when it comes to congressional redistricting.83See infra Part II. How far removed from the actual legislature or legislators is too much in each context? The next Part applies our proposed analytical framework to all existing congressional redistricting commissions to determine the likelihood of their constitutionality under either version of ISLT.

II. Legislative Control over Congressional Redistricting Commissions and Potential Implications Under ISLT

No two congressional redistricting commissions are exactly alike. However, they do all share three key criteria that will likely determine their constitutionality under ISLT. The first criterion is commission creation, or how the commission came to be. The second is commission membership and selection: who sits on the commission and how did they come to occupy one of those coveted seats? The third criterion, plan enactment, is also critical: what part does the commission play in creating and enacting the congressional district plan for the state?

When considering ISLT and its impact on congressional redistricting commissions’ constitutionality, these procedural criteria matter far more than the substantive elements of how commissions draw their maps.84Petitioners in Moore employed a “procedural” versus “substantive” distinction in their arguments for ISLT. They posited that, if the Supreme Court rejected the principle that ISLT demands absolute insulation from state courts when legislating on federal election laws, the Court should still have limited state courts’ involvement to adjudicating questions of procedural, rather than substantive, election laws passed by the state legislature. See, e.g., Brief for Petitioners at 24–25, Moore v. Harper, 142 S. Ct. 1089 (2022) (No. 21-1271) [hereinafter Moore Petitioner Brief]; Moore Transcript, supra note 56, at 38, 61–62. We do not use the distinction in this way. Instead, we merely use the distinction to demonstrate the different types of power elements at play when assessing the constitutionality of congressional redistricting commissions under ISLT. In other words, the constitutionality of a commission under ISLT would not turn on the substantive redistricting criteria states use to draw their maps, such as compactness, contiguity, or respect for municipal boundaries. Instead, constitutionality would depend on the procedural criteria named above.85Of course, the federal Constitution still places general substantive requirements on redistricting, like avoiding the predominance of race over other districting criteria. See, e.g., Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630, 647 (1993); Cooper v. Harris, 581 U.S. 285, 306 (2017). The Court left room for various versions of ISLT to become law in the future, with multiple forms of the theory suggesting that it might be unconstitutional for any entity that is not the legislature to draw those maps. Ultimately, the fate of a congressional redistricting commission depends on one key question: does the state legislature—in the face of an operative congressional redistricting commission—maintain a sufficient level of legislative control over the congressional redistricting process for each of our three criteria?

Two questions derive from this primary one: 1) does a state legislature exercise enough control to meet ISLT-Max’s higher threshold (in other words, does it retain “primary responsibility” over congressional redistricting as Justice Gorsuch requires);86See Democratic Nat’l Comm. v. Wis. State Legislature, 141 S. Ct. 28, 29 (2020) (mem.) (Gorsuch, J., concurring in the denial of application to vacate stay). or, if not, 2) does the legislature retain enough control to at least meet the lower threshold of ISLT-Lite (i.e. does the commission possess only an “auxiliary role” in congressional redistricting compared to the legislature’s “primary” one, as Chief Justice Roberts requires)?87See Ariz. State Legislature v. Ariz. Indep. Redistricting Comm’n, 576 U.S. 787, 847–48 (2015) (Roberts, C.J., dissenting). If a state legislature does not wield sufficient control to meet the respective ISLT-Max or ISLT-Lite threshold for any given criterion, then we predict that the state’s commission would automatically fail under the respective ISL theory.

After determining these thresholds, this Part tries to answer these key questions about legislative control by using a totality of the circumstances test to assess each congressional redistricting commission’s potential to survive under either ISLT. This test requires analyzing each commission’s creation, membership and selection, and plan enactment processes to determine how much congressional redistricting authority the commission possesses compared to the state legislature. We also comparatively analyze these commissions to better understand their differences and how these differences impact their constitutionality under ISLT. After these assessments, we predict each commission’s likelihood for constitutionality under both ISLT-Max and -Lite based on how the three criteria map onto each commission.

We employ a spectrum model charting each existing congressional redistricting commission’s position based on these three criteria to project the commission’s likely validity under ISLT-Max and ISLT-Lite. The spectrum model is a linear diagram that depicts a range from least (left) to most (right) legislative control for each criterion. We break down each of the three key procedural criteria into subparts, categorized by the level of legislative involvement, then assign each commission to the appropriate subpart. The less control the state legislature exercises over a procedural element, the more likely a court would hold that particular commission unconstitutional under a given ISLT, and vice versa.88Some commissions in our analysis have contingency plans should their first line process fail. We analyze the likely result of a constitutional challenge based on the commission’s process working from the initial stage. We do not analyze what would happen if the processes were found severable and the contingency plan (e.g., a state supreme court draws the maps if the legislature rejects every commission-drawn map) was invoked. We then create an overall spectrum model based on the assessments of how well the individual commissions fare on these three criteria. The final model plots the likelihood of a federal court upholding each commission’s congressional districting power as constitutional under ISLT-Max or ISLT-Lite.

On each of our models, we use a dashed line to demarcate the minimum thresholds required to satisfy each criterion under each theory. Think of these dashed lines as delineating how “tall” (in terms of legislative control) each commission must be to “ride the ride” (be constitutional). If the commission does not reach the minimum threshold for any criterion, it must fail under that theory. It cannot “ride the ride.” However, achieving one threshold does not necessarily mean a commission is constitutionally safe. For a commission to guarantee its survival under both ISLTs, the commission must meet both threshold requirements across all three criteria. The final model in Section II.D shows the commissions that are likely to survive ISLT-Max, ISLT-Lite, or neither based on these thresholds and assessments of the totality of the circumstances.

A. Criterion 1: Commission Creation

We break down the “commission creation” criterion into six subcategories, ordered from least to most legislative control: whether the commission was created by 1) executive order, 2) voter-led ballot initiative, 3) constitutional convention, 4) voter-initiated state statute, 5) legislatively referred constitutional amendment, or 6) legislative statute.

| Executive Order | Maryland |

| Voter-Led Ballot Initiative | Arizona, California, Michigan |

| Constitutional Convention | Connecticut, Hawaiʻi, Montana |

| Voter-Initiated State Statute | Utah |

| Legislatively Referred Constitutional Amendment | Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Maine, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Virginia, Washington |

| Legislative Statute | Indiana, Iowa, New Mexico |

Table 1: How States Created Their Commissions89See Maryland Citizens Redistricting Commission, Maryland.Gov, https://redistricting.maryland.gov/Pages/commission.aspx [perma.cc/QM9T-8X2T] (Maryland); Colleen Mathis, Daniel Moskowitz & Benjamin Schneer, The Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission: One State’s Model for Gerrymandering Reform 3 (2019), https://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/az_redistricting_policy_brief.pdf [perma.cc/NEH4-7LV7] (Arizona); Citizens Redistricting Commission, supra note 8 (California); We Ended Gerrymandering in Michigan, Voters Not Politicians, https://votersnotpoliticians.com/redistricting [perma.cc/YP58-WA8D] (Michigan); Norman-Eady & Sullivan, supra note 11 (Connecticut); Hawaii Provisions for Future Reapportionment, Amendment 2 (1968), supra note 11 (Hawaiʻi); Joe Lansom, Montana Constitutional Authority for Independent, Autonomous Commission, Mont. Districting Comm’n (June 10, 2020), https://leg.mt.gov/content/Districting/2020/Meetings/July-2021/lamson-memo-2020-districting-litigation-history.pdf [perma.cc/97BW-LRSP] (Montana); Utah Proposition 4, Independent Advisory Commission on Redistricting Initiative (2018), Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Utah_Proposition_4,_Independent_Advisory_Commission_on_Redistricting_Initiative_(2018) [perma.cc/6RNH-PVF6] (Utah); Cain, supra note 8, at 1819 (Alaska); Gordon Harrison, Alaska Legis. Affs. Agency, Alaska’s Constitution: A Citizen’s Guide 113–15 (5th ed. 2018) (same); Colorado Amendment Y, Independent Commission for Congressional Redistricting Amendment (2018), Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Colorado_Amendment_Y,_Independent_Commission_for_Congressional_Redistricting_Amendment_(2018) [perma.cc/CL66-KWBL] (Colorado); Idaho Legis. Servs. Off. Comm’n on Redistricting, Idaho’s First Commission on Redistricting 1 (2001-2002) (Idaho); Amendments to the Maine Constitution, 1820 – Present, Me. State Legislature, https://www.maine.gov/legis/lawlib/lldl/constitutionalamendments [perma.cc/3YNA-R69V] (Maine); Magyar, supra note 11 (New Jersey); Laws & Regulations: Relevant State and Federal Statutory Provisions, N.Y. State Indep. Redistricting Comm’n, https://www.nyirc.gov/laws-regs#_ftn1 [perma.cc/7SPS-WYAG] (New York); Ohio Bipartisan Redistricting Commission Amendment, Issue 1 (2015), Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Ohio_Bipartisan_Redistricting_Commission_Amendment,_Issue_1_(2015) [perma.cc/P4MY-PFMK] (Ohio); Virginia Question 1, Redistricting Commission Amendment (2020), Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Virginia_Question_1,_Redistricting_Commission_Amendment_(2020) [perma.cc/NX4N-YGD3] (Virginia); Washington Redistricting Commission, SJR 103 (1983), Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Washington_Redistricting_Commission,_SJR_103_(1983) [perma.cc/FCE9-77AW] (Washington); Ind. Code. § 3-3-2-2 (2023) (Indiana); Ed Cook, Legis. Servs. Agency, R-9461, Legislative Guide to Redistricting in Iowa 13 (2007), https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/publications/LG/9461.pdf [perma.cc/Q2T8-6W9E] (Iowa); Sara Swann, N.M. Legislature Gets Behind Only Partial Mapmaking Independence, Fulcrum (Mar. 22, 2021), https://thefulcrum.us/redistricting/new-mexico-redistricting [perma.cc/B2K7-KQES] (New Mexico); N.M. Stat. Ann. § 1-3A-1 (2021) (same).

To meet the ISLT-Lite threshold, a congressional redistricting commission must have at least been created by a state constitutional convention. This includes only those commissions created by such a convention, or a voter-initiated state statute, legislatively referred constitutional amendment, or legislative statute. Only with these creation procedures does the commission arguably not render the state legislature “auxiliary” in the congressional redistricting process. For a commission created by executive order, the legislature has zero involvement in making the commission90The Maryland Constitution provides that the governor “shall prepare a plan setting forth the boundaries of the [state] legislative districts” to then propose to the legislature for consideration. Md. Const. art. III, § 5; see also Md. Citizens Redistricting Comm’n, Final Report of the Maryland Citizens Redistricting Commission 3 (2022); Exec. Order No. 01.01.2021.02, 48–4 Md. Reg. 153 (Feb. 12, 2021). and the legislature cannot amend an executive order once it is issued. Therefore, the legislature exerts the least amount of control over a commission created by executive order. Voter-led ballot initiatives, where voters can directly amend their state constitutions by vote, are a close second compared to executive orders. Legislators are capable of amending the voter-led changes to their state constitutions but have no control over the initiation and enactment of a ballot measure.91See Amending State Constitutions, Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Amending_state_constitutions [perma.cc/24HL-VD6J]; see also Initiative and Referendum Processes, Nat’l Conf. of State Legislatures (Jan. 4, 2022), https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/initiative-and-referendum-processes [perma.cc/ACS9-8YVJ]. However, garnering sufficient state legislative support to amend a constitution is quite difficult, rendering the legislature’s ability to change the language enshrined in the constitution by a voter-led ballot initiative largely out of its control.92See Amending State Constitutions, supra note 91(describing many states as requiring at least two thirds of the legislature to agree to an amendment before it is placed on a ballot for voter approval). With no, or practically zero, legislative control over this creation process for these types of commissions, the commission almost certainly renders the legislature “auxiliary,” causing these commissions to fail even under ISLT-Lite.

Commissions created by constitutional convention allow state legislatures to exert more control. Although rules for constitutional conventions vary by state, the three commissions created by constitutional convention all share the same key characteristic: the legislature initiates the commission-creation process by requesting a constitutional convention.93See Norman-Eady & Sullivan, supra note 11 (Connecticut); General Montana State History,US50, https://theus50.com/montana/history.php [perma.cc/2UYW-6Y3Q] (Montana); Hawaii Provisions for Future Reapportionment, Amendment 2 (1968), supra note 11 (Hawaiʻi); Rules About Constitutional Conventions in State Constitutions, Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Rules_about_constitutional_conventions_in_state_constitutions [perma.cc/8ZLM-NKBM]. Then, the legislature can refer amendments to the constitution. So, while the legislature itself does not operate as the voting body at a constitutional convention, the constitutional convention avenue does provide the state legislature with multiple opportunities to influence the commission’s creation. Commissions created by voter-initiated state statutes allow for still more legislative control because voters propose and enact them with zero input from legislators. The legislature can amend the language of these statutes, however, by simply enacting a new statute.94See, e.g., Laws Governing the Initiative Process in Utah, Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Laws_governing_the_initiative_process_in_Utah [perma.cc/USR9-PPB4]. The state legislature can typically pass a new statute much more easily than it can amend the state constitution via constitutional convention or otherwise.95See Moore Transcript, supra note 56, at 15–20, 59 (Statement by David H. Thompson) (“Statutes are always less problematic under the Elections Clause because they can be repealed. They can be rewritten by the state legislature.”). These types of commissions likely meet the threshold to survive under ISLT-Lite because these state legislatures were intimately involved in the creation process (constitutional convention route) or could easily alter the makeup of the commission later by majority-voted statute (voter-initiated state statute route).96The legislature did precisely this in Utah. See DeArbea Walker, Utah Voters Want Independent Redistricting. GOP Lawmakers Are Fighting It., Ctr. for Pub. Integrity (Oct. 6, 2022), https://publicintegrity.org/politics/elections/who-counts/utah-voters-want-independent-redistricting-gop-lawmakers-are-fighting-it [perma.cc/CL4J-QQ37]. Therefore, the state legislatures have more than an “auxiliary” role; however, the legislatures still likely do not have “primary responsibility” in the redistricting process under this criterion to meet ISLT-Max’s survival threshold because nonlegislators have the ability to initially draft and create the commissions without legislative input.

To survive under ISLT-Max, a congressional redistricting commission must have at least been created by a legislatively referred constitutional amendment. This means that only those commissions created by such an amendment, or those created by legislative statute, meet ISLT-Max’s threshold for this criterion and would likely survive a constitutional challenge. Only with these creation procedures does the legislature arguably retain “primary authority” over redistricting.

Commissions created by legislatively referred constitutional amendments give even greater control to the state legislature. The legislative referral process sees the legislature freely delegate its redistricting authority to the commission on its own initiative if voters approve a state constitutional amendment. The legislature can later amend the commission’s structure through a similar process should it decide to change course. While the state constitution is almost certainly harder to amend than a state statute,97See supra note 95 and accompanying text. the legislature at least has the potential for influence and control over the commission’s creation at both ends of this amendment process. The legislature’s responsibility for initiating the change (while knowing how difficult it is to reverse course) underlines the strength of legislative control in this category.

Finally, the legislature’s control is at its apex when it creates a redistricting commission via a regular state statute. Using that process, the legislature, acting of its own accord, chooses to give away its redistricting power. It retains power to alter the extent of the commission’s control over the redistricting process, or vitiate it completely, through the normal legislative process. Both of these creation procedures rest almost entirely in the control of the legislature, not voters or any other state entity. Therefore, the legislature maintains “primary” control over the redistricting process, rendering the commissions in these states consistent with ISLT-Max at least on this criterion.

Model 1: Commission Creation Spectrum Model

B. Criterion 2: Commission Membership & Selection

We break down the “Commission Membership & Selection” criterion into seven subcategories, ordered from least to most legislative control: 1) legislators are not involved, 2) legislators strike some applicants from the commissioner pool, 3) legislators propose a commissioner pool for 50% of commissioners, 4) legislators choose less than 50% of commissioners, 5) legislators choose at least 50% of commissioners, 6) legislators are 50% of commissioners, and 7) all commissioners are legislators.98We believe that, for Justice Gorsuch, there is a material difference between a legislator serving on the commission and their appointee, even if the appointee is a reliable proxy (e.g., friend, donor, political party delegate, employee, or family member). Justice Gorsuch emphasizes these formal roles and labels in his ISLT writings. See supra Part I.

Table 2: Legislative Power over Commissioners99Md. Const. art. III, § 5 (Maryland); Exec. Order No. 01.01.2021.02, 48–4 Md. Reg. 153 (Feb. 12, 2021) (same); Cal. Gov. Code § 8252 (West 2021) (California); State of California, Application and Selection Process, We Draw the Lines CA, https://wedrawthelines.ca.gov/transition/selection [perma.cc/9Z6K-9BPC] (same); Mich. Const. art. IV, § 6, cls. 1–2 (Michigan); Colo. Const. art. V, § 44.1, cls. 5–10 (Colorado); Alaska Const. art. VI, § 8 (Alaska); N.M. Stat. Ann. § 1-3A-3 (2021); Ohio Const. art. XI, § 1 (Ohio); N.J. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 1 (New Jersey); Me. Const. art. IV, pt. III, § 1-A (Maine); Idaho Const. art. III, § 2, cl. 2 (Idaho); Ariz. Const. art. IV, pt. II, § 1, cls. 3–6 (Arizona); Mont. Const. art. V, § 14, cl. 2 (Montana); N.Y. Const. art. III, § 5-b (New York); Wash. Const. art. II, § 43, cl. 2 (Washington); Utah Code Ann. § 20A-20-201 (2023) (Utah); Haw. Const. art. IV, § 2 (Hawaiʻi); Va. Const. art. II, § 6-A (Virginia); Conn. Const. art. III, § 6 (Connecticut); Kristin Sullivan & Kristen Miller, Conn. Off. of Legis. Rsch., Connecticut’s Redistricting Procedures and Deadlines, 2016-R-0268 (2016) (same); State of Connecticut, Frequently Asked Questions, Conn. Gen. Assembly, https://www.cga.ct.gov/rr/tfs/20210401_2021%20Redistricting%20Project/faq.asp [perma.cc/NPP9-MUR9] (same); Ind. Code § 3-3-2-2 (2023) (Indiana).

| Legislators are not involved | Maryland |

| Legislators strike some applicants from the commissioner pool | California, Michigan |

| Legislators propose commissioner pool for 50% of commissioners | Colorado |

| Legislators choose fewer than 50% of commissioners | Alaska (2/5 Commissioners) |

| Legislators choose at least 50% of commissioners | New Mexico (4/7 Commissioners), Ohio (4/7), New Jersey (8/13), Idaho (4/6), Maine (10/15), Arizona (4/5), Iowa (4/5), Montana (4/5), New York (8/10), Washington (4/5), Utah (6/7), Hawaiʻi (8/9) |

| Legislators are 50% of commissioners | Virginia |

| All commissioners are legislators | Connecticut, Indiana |

To meet the ISLT-Lite threshold, state legislatures must have the power to choose, by appointment, at least some commissioners to serve on the commission. The appointment power, regardless of if state law allows legislators to appoint themselves or proxies, will help ensure the legislature is not rendered “auxiliary” in the process. The legislature has the least legislative control over commissions where legislators cannot sit as commissioners themselves, influence the pool from which commissioners are selected, or appoint anyone to serve as a commissioner. In this scenario, the legislature is completely excluded from deciding who sits as a commissioner, and hence, who draws and proposes the commission’s maps. Commissions where a nonlegislative entity such as the state’s secretary of state or supreme court chooses the commissioners, but the legislators can at least partially influence the pool of potential commissioners by striking applicants, allow for more legislative control over commissioner selection.100See, e.g., Mich. Const. art. IV, § 6. Legislators exert even greater control when they can directly choose the pool of potential commissioners for at least 50% of the commissioner slots from which a nonlegislative state authority then appoints the commissioners.101For Colorado’s congressional redistricting commission, individuals must apply for a commissioner position. A “nonpartisan staff” screens applicants to ensure they comply with prerequisite character requirements. Colo. Const. art. V, § 44.1. Then, the chief justice of the Supreme Court of Colorado creates a panel, consisting of three retired justices of the Colorado Supreme Court or judges of the Colorado Court of Appeals, to select commissioners from this pool. Id. The panel then cuts the pool down to 150 before randomly selecting six of the qualified candidates as commissioners. Id. The state legislature only has some control over the selection of four commissioners. The majority and minority leaders from the state House and Senate each create a pool of ten candidates chosen from eligible applicants vetted by the nonpartisan staff. After the leaders choose their pools, the panel itself decides who to select as a commissioner from each of these pools. Finally, the justice panel chooses two unaffiliated commissioners. Strictly following this process produces a commission with four democrat, four republican, and four unaffiliated commissioners. Id. These two categories—where the legislature has influence over the commissioner pool—differ primarily in the number of potential commissioners the legislature has control over and which entity initially chooses who enters that pool. In the first subcategory, a nonlegislative entity determines the pool, from which the legislature strikes only a handful of options, leaving the nonlegislative entity with dozens of potential commissioners from which to choose. By contrast, for the second subcategory, the legislature wields greater control by proposing a large percentage of the commissioners in the pool, but a nonlegislative entity still wields significant control over choosing who becomes a commissioner from that pool. In all three of the above categories, the legislature is either entirely cut out of, or maintains merely a minor role in, influencing who becomes a commissioner with the power to draw the maps. As such, these commissions likely fail to meet the requirements of ISLT-Lite.

State legislatures have much greater control over commissions where they can directly appoint individuals to serve as commissioners, instead of just influencing the pool of potential commissioners, because it remains within the power of the legislature—not another state entity—to choose the people that become commissioners. The power to directly appoint at least some commissioners to the commission is likely the smallest amount of legislative control that survives ISLT-Lite under this criterion. If the state legislature possesses any less control than a direct appointment power, then the commission arguably plays more than just an “auxiliary role” in redistricting compared to the legislature. Of the two categories meeting this description, the legislature, naturally, has less power over commissions where it chooses less than 50% of commissioners. For the commissions where the legislature maintains the power to appoint at least 50%, but not 100%, of commissioners, it has greater influence over the redistricting process by controlling more seats on the commission. Most commissions fall within this latter appointment category. The appointment procedures vary greatly between these different states,102In New Mexico, for example, the commission consists of seven commissioners. N.M. Stat. Ann. § 1-3A-3 (2023). The majority and minority leaders in both the state house and senate appoint one commissioner each. Id. This ensures two commissioners are appointed by democrats and two by republicans. See Party Control of New Mexico State Government, Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Party_control_of_New_Mexico_state_government [perma.cc/PU86-AWQC]. The independent State Ethics Commission appoints the fifth and sixth commissioners, “who shall not be members of the largest or second largest political parties in the state.” N.M. Stat. Ann. § 1-3A-3 (2023). The State Ethics Commission also appoints the seventh commissioner, “who shall be a retired justice of the New Mexico Supreme Court or a retired judge of the New Mexico Court of Appeals, and who shall chair the committee.” Id. Among other restrictions, state law prohibits public officials, candidates for public office, lobbyists, and officeholders in political parties at the state or federal level currently or within the last two years from serving on the commission. Id. §§ 1-3A-3 to -4. Washington’s process excludes similarly conflicted citizens from its commission. Wash. Rev. Code § 44-05-050 (West 2023); Wash. Const. art. II, § 43. But see infra note 104 and accompanying text (detailing Hawaiʻi’s appointment procedures, which differ significantly from New Mexico’s and Washington’s). but most states disallow their state legislatures from appointing current local, state, or federal officeholders to the commission.103See, e.g., supra note 102 (New Mexico; Washington). Some do, however.104See, e.g., Haw. Const. art. IV, § 2 (Hawaiʻi).

Regardless of these more specific scenarios, commissions in the “at least 50%” category all likely pass muster under ISLT-Lite because the legislature maintains a greater than “auxiliary” role in the process by choosing how to compose a majority of the commission’s membership. Arguably, these commissions could have met the ISLT-Max threshold of “primary responsibility” as well; however, the common fact that the appointees within the legislatures’ control either cannot or may not (depending on the state) be legislators themselves sufficiently breaks legislative control over the commissions such that those processes do not meet the “primary” requirement under ISLT-Max. Instead, these appointees are more analogous to “other state officials,” whom Justice Gorsuch specifically prohibits under ISLT-Max.105Democratic Nat’l Comm. v. Wis. State Legislature, 141 S. Ct. 28, 29 (2020) (mem.) (Gorsuch, J., concurring in the denial of application to vacate stay). So, while insufficient to satisfy the demands of ISLT-Max, these appointee-commission structures still likely survive constitutional scrutiny under ISLT-Lite.

The lowest level of legislative control a state legislature can exercise over a commission’s membership selection process to survive ISLT-Max is likely where at least 50% of the commissioners are guaranteed to be legislators themselves. At this level of control and more, the legislature arguably retains “primary authority” over redistricting because it ensures that legislators, as representatives of the legislature itself, constitute the “primary” voting bloc on the commission. Without support from the legislators on the commission, the commission cannot pass any plan, rendering the legislators’ votes ones of “first rank, importance, or value.”106Primary, supra note 65. Through these commissions, legislators directly represent the state legislature’s own interests, rather than wielding only indirect power through appointments. Finally, legislative control over the commissions is at its apex when state legislators hold every seat on the commission. In this last scenario, there is no question that the legislature maintains “primary responsibility” over the commission’s membership, as no other entity plays a role and no other nonlegislative individual is likely to sit on the commission. This almost guarantees that these commissions would survive ISLT-Max.

Model 2: Commission Membership & Selection Spectrum Model

C. Criterion 3: Plan Enactment

We break down the “Plan Enactment” criterion into six subcategories, ordered from least to most legislative control: 1) commissions draw, pass, and enact maps, 2) commissions choose maps drawn by legislative staff, subject to approval by the state supreme court, 3) commissions draw maps, requiring approval by the legislature and subject to gubernatorial veto, 4) commissions draw maps requiring only approval by the legislature, 5) commissions draw and pass maps only if the legislature fails to pass maps, and 6) commissions draw and pass maps only if the legislature fails to pass maps, subject to change or voidance by legislative statute.