Error Aversions and Due Process

William Blackstone famously expressed the view that convicting the innocent constitutes a much more serious error than acquitting the guilty. This view is the cornerstone of due process protections for those accused of crimes, giving rise to the presumption of innocence and the high burden of proof required for criminal convictions. While most legal elites share Blackstone’s view, the citizen jurors tasked with making due process protections a reality do not share the law’s preference for false acquittals over false convictions.

Across multiple national surveys sampling more than 12,000 people, we find that a majority of Americans consider false acquittals and false convictions to be errors of equal magnitude. Contrary to Blackstone, most people are unwilling to err on the side of letting the guilty go free to avoid convicting the innocent. Indeed, a sizeable minority view false acquittals as worse than false convictions; this group is willing to convict multiple innocent persons to avoid letting one guilty person go free. These value differences translate into behavioral differences: we show in multiple studies that jury-eligible adults who reject Blackstone’s view are more accepting of prosecution evidence and are more conviction-prone than the minority of potential jurors who agree with Blackstone.

These findings have important implications for our understanding of due process and criminal justice policy. Due process currently depends on jurors faithfully following instructions on the burden of proof, but many jurors are not inclined to hold the state to its high burden. Courts should do away with the fiction that the reasonable doubt standard guarantees due process and consider protections that do not depend on jurors honoring the law’s preference for false acquittals, such as more stringent pretrial screening of criminal cases and stricter limits on prosecution evidence. Further, the fact that many people place crime control on par with, or above, the need to avoid wrongful convictions helps explain divisions in public opinion on important policy questions like bail and sentencing reform. Criminal justice proposals that emphasize deontic concerns without addressing consequentialist concerns are unlikely to garner widespread support.

Introduction

Christopher Michael Sanchez had the right idea. During voir dire in his trial for assault on a public servant, Mr. Sanchez’s lawyer sought to ask the venire “to rate on a scale of one to five whether it agreed or disagreed with the statement that it is better for ten people [to] go free than one be convicted.”1Sanchez v. State, No. 08-17-00244-CR, 2019 WL 926139, at *1 (Tex. Ct. App. Feb. 26, 2019). The judge disallowed use of the scale but permitted counsel to ask prospective jurors whether they agreed or disagreed with “Blackstone’s ratio,”2Id. at *4–*5. that it is “better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer.”34 William Blackstone, Commentaries *352. “Blackstone’s ratio” is one label applied to William Blackstone’s famous dictum expressing the view that the law should accept multiple acquittals of the guilty to avoid one wrongful conviction. See id.

The appellate court concluded that this alteration in questioning was not so important as to have affected Mr. Sanchez’s substantial rights.4Sanchez, 2019 WL 926139, at *5. The court correctly noted that prospective jurors might have disagreed with Blackstone’s ratio because they rejected the idea that any error was acceptable or because they disagreed with the particulars of the math—that the posited ratio was too high or too low.5Id. Thus, no matter how the initial question was posed, further questioning was needed to understand how jurors’ views on the Blackstone ratio might have affected their interpretation of the state’s “beyond a reasonable doubt” burden of persuasion.6Id. (“Counsel would need to delve into a venireperson’s thought process, and no follow-up questions were asked here.”). Because counsel did not seek to ask further questions on the topic, the judge’s restriction on voir dire did no harm.7Id. (“We thus cannot tell how helpful or not the answer to the question would be in exercising peremptory strikes. Consequently, we cannot determine how helpful or not a scaled response to the same question would be.”).

Despite the somewhat flawed execution, Mr. Sanchez and his counsel were on to something important, for many prospective jurors do not share Blackstone’s view.8In the Sanchez case, for instance, a substantial number disagreed with Blackstone’s ratio. Of the sixty-one prospective jurors asked the question, “49 answered that they disagreed with the statement; 5 answered that they agreed with the statement; and 7 were undecided or equivocal.” State’s Brief at 29, Sanchez, 2019 WL 926139 (No. 08-17-00244-CR), 2018 WL 4381508. Still more troubling, those who do not share that view are unlikely to give the defendant the same benefit of the doubt as those who agree with Blackstone.

We establish both propositions empirically. Across several national surveys, we have found that far more Americans reject Blackstone’s view than endorse it: a majority equate the harms of false acquittal and false conviction, and a sizeable minority deem false acquittals more harmful to society than false convictions.9Theorists often label the error of convicting an innocent person a “type-1 error” and the error of acquitting a guilty person a “type-2 error,” terminology that is cryptic to those not familiar with the literature and perhaps implies one error is more fundamental than the other. To avoid confusion or a suggestion of priority between the errors, we use the terms “false conviction” and “false acquittal” to refer to the two respective factual errors that can occur in a criminal trial (i.e., “false” here means a trial outcome that deviated from ground truth with respect to who committed the acts in question). The majority of Americans are unwilling to trade multiple false acquittals to avoid one false conviction, and many are willing to accept multiple false convictions to avoid one false acquittal.10See infra Section I.B. These value differences matter greatly: those who see false acquittals on par with, or worse than, false convictions are more receptive to the prosecution’s evidence and are easier for the prosecution to persuade.11See infra Part III. We observe these value and behavioral differences in multiple samples of the U.S. population through various trial error aversions measurements, and the pattern holds across political groups.12See infra Part II. Perhaps still more surprising, we find that this is not necessarily a partisan preference. Majorities of Democrats, Republicans, and Independents all view false convictions and false acquittals to be errors of equal magnitude.13See infra Part II.

Our empirical evidence establishes that the error aversions held by the general public depart dramatically from long-accepted constitutional norms.14For prior scholarship exploring the relationship error aversions have with legal outcomes and showing that many laypeople do not share the assumptions of our constitutional system, see Gregory Mitchell & Brandon L. Garrett, The Impact of Proficiency Testing Information and Error Aversions on the Weight Given to Fingerprint Evidence, 37 Behav. Scis. & L. 195 (2019) (data available at https://osf.io/r63tz/?view_only=0518053af2b24dada0047ae4aa91cfd0). The term “error aversion” simply refers to the desire to avoid an error. See infra note 27. Blackstone proffered his famous ratio in 1765,15See supra note 3. but the notion that false convictions constitute a greater injustice than false acquittals animated the law at least as early as biblical times. Blackstone’s 10:1 ratio is just one of many formulations of the idea that false convictions outweigh false acquittals morally and legally.16See generally Alexander Volokh, Aside, n Guilty Men, 146 U. Pa. L. Rev. 173 (1997) (tracing the history of the idea that trials should shift the risk of error in favor of the accused). We follow Professor Epps’ interpretation of the Blackstone principle—the idea that false convictions must outweigh false acquittals. Daniel Epps, The Consequences of Error in Criminal Justice, 128 Harv. L. Rev. 1065, 1068 (2015) (defining the “Blackstone principle” as the notion that “in distributing criminal punishment, we must strongly err in favor of false negatives (failures to convict the guilty) in order to minimize false positives (convictions of the innocent), even if doing so significantly decreases overall accuracy”). In the United States, the Supreme Court first invoked the Blackstone principle in 1895 to justify the presumption of innocence17Coffin v. United States, 156 U.S. 432, 453–56 (1895) (invoking the principle to explain the presumption of innocence and tracing it to Roman law). and again in 1970 to justify incorporating the requirement of the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt burden of persuasion in criminal cases under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.18See In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358, 361–64 (1970). Justice Harlan’s concurrence in Winship contains the most oft-cited statements from the Court discussing the law’s preference for false acquittals. See id. at 372 (Harlan, J., concurring). Between its decisions in Coffin and Winship, the Court also invoked the Blackstone principle to justify the Fourth Amendment’s limits on search and seizure. See Henry v. United States, 361 U.S. 98, 104 (1959) (“Under our system suspicion is not enough for an officer to lay hands on a citizen. It is better, so the Fourth Amendment teaches, that the guilty sometimes go free than that citizens be subject to easy arrest.”). The fundamental due process protections for criminal defendants at trial—the presumption of innocence and the requirement of proof of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt—arise from the principle that the state should impose punishment only on the clearest of proof that the accused committed the crime charged, even if this high bar means some wrongdoers will escape punishment. In a very real sense, the Supreme Court understands due process as a manifestation of the Blackstone principle: “With reputation, liberty, and at times even life on the line, every legal and moral precept counsels caution in bringing down the hammer of justice on a criminal defendant.”19J. Harvie Wilkinson III, The Presumption of Civil Innocence, 104 Va. L. Rev. 589, 597, 600–03 (2018).

Although occasionally questioned,20See, e.g., Ronald J. Allen & Larry Laudan, Deadly Dilemmas, 41 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 65, 68 (2008) (“At some point in this country’s history, perhaps discussing just one side of the equation was laudable, but now is the time to consider the other side as well.”); Jeremy Bentham, A Treatise on Judicial Evidence 198 ((M. Dumont ed. & trans., London, J.W. Paget 1825) (“All these candidates for the prize of humanity have been outstripped by I know not how many writers, who hold, that, in no case, ought an accused person to be condemned, unless the evidence amount to mathematical or absolute certainty. According to this maxim, nobody ought to be punished, lest an innocent man be punished.”); Epps, supra note 16, at 1069 (“This Article seeks to give the Blackstone principle the careful attention it deserves.”). for the most part, judges, lawyers, and legal scholars accept as correct the proposition that the need to minimize wrongful convictions justifies procedural asymmetries that favor the defendant.21See Epps, supra note 16, at 1069 (“[S]erious and sustained discussions of the principle’s costs and benefits are few and far between. Most simply treat it as a self-evident truth.”). Indeed, one scholar labeled Blackstone’s ratio the “Mount Everest of legal mantras.”22Laura I. Appleman, A Tragedy of Errors: Blackstone, Procedural Asymmetry, and Criminal Justice, 128 Harv. L. Rev. F. 91, 91 (2015). Perhaps because legal education inculcates this mantra,23Indeed, legal education inculcates the Blackstonian view: “Enroll in law school and you will be taught, within the first year, a revered maxim of criminal law: ‘[B]etter that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer.’ ” Joel S. Johnson, Note, Benefits of Error in Criminal Justice, 102 Va. L. Rev. 237, 238 (2016) (alteration in original) (footnote omitted). rarely do judges, lawyers, or legal scholars question whether nonlawyers agree with it.24See, e.g., Epps, supra note 16, at 1151 (“Most of us, if required to decide whether someone was guilty of a crime, would almost certainly choose to err strongly against being responsible for wrongly imposing a harsh penalty.”). The prevailing wisdom seems to be that while jurors may not always agree a high burden of proof should apply in every case, jurors will follow the standard jury instructions and err in favor of the accused.25For an excellent discussion of the realities of jury trials and how to align jury behavior with the legal ideal, see generally Jack B. Weinstein & Ian Dewsbury, Comment on the Meaning of ‘Proof Beyond a Reasonable Doubt’, 5 Law, Probability & Risk 167 (2006).

Our first results showing widespread rejection of the Blackstone ratio were so surprising and potentially disruptive that we tested their robustness multiple times, using a series of large samples drawn from the entire U.S. population and multiple measurement methods.26We describe our methods, the populations sampled, and the limitations of these designs in Section I.B. The underlying data is also all available on the Open Science Framework. The picture remained consistent and clear: far more Americans view false acquittals and false convictions to be errors of equal magnitude than those who view false convictions to be the more serious error, and a sizeable minority consider false acquittals to be the more serious error. We detail these results in Part I and explain why prior studies missed this important finding.

In Part II, we examine the demographic, experiential, and ideological correlates of these different error aversions.27Preference and aversion are two sides of the same coin, with the former often used to refer to positive desires or outcomes one wants to experience, and the latter used to refer to negative desires or outcomes one wants to avoid. We usually speak of people’s aversions to false convictions and false acquittals, but we occasionally speak in terms of error preferences as well. We find that people’s error aversions defy simple ideological assumptions: a majority of Democrats, Republicans, and Independents all see false convictions and false acquittals as equally harmful, and many Democrats deem false acquittals more harmful than false convictions. Concerns about the criminal justice system are better predictors of error aversions: those equally averse to the two trial errors tend to have greater fears of being a crime victim and of being falsely accused of a crime, and these fears transcend party labels.

In Part III, we address the behavioral consequences of these different error aversions. We show that a person’s error aversions are important predictors of how they will behave as jurors. For example, in one of our recent studies, the conviction rate among people who prioritize the avoidance of false acquittals was 58 percent, compared to a conviction rate of 25 percent among those who prioritize the avoidance of false convictions, even though these two groups were exposed to the same evidence.28Brandon L. Garrett, William E. Crozier & Rebecca Grady, Error Rates, Likelihood Ratios, and Jury Evaluation of Forensic Evidence, 65 J. Forensic Scis. 1199, 1203–04 (2020). We find similar results in other studies examining how jurors respond to expert evidence and eyewitness evidence.29See, e.g., Brandon L. Garrett, Alice Liu, Karen Kafadar, Joanne Yaffe & Chad S. Dodson, Factoring the Role of Eyewitness Evidence in the Courtroom, 17 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 556, 571 (2020); Mitchell & Garrett, supra note 14, at 206.

In Part IV, we turn to the larger implications of our findings for legal doctrine and crime policy. Herbert Packer famously described two competing models of criminal justice: (1) the crime control model, emphasizing the need to repress criminal conduct and an outright “presumption of guilt,” and (2) the due process model, which emphasizes the presumption of innocence, the risk of convicting the innocent and procedural protections for the accused.30Herbert L. Packer, Two Models of the Criminal Process, 113 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1, 9–14 (1964). Our results suggest that most people view both models as equally important. This finding has substantial implications for legal doctrine, from evidence rules to criminal procedure more broadly, which assume the trial is the “main event” and a beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard is the key protection for the accused.

Put simply, our findings suggest that legal doctrines that assume the median juror is more averse to false convictions than false acquittals proceed from an empirically false premise. Lawyers should rethink how they select jurors and present evidence, and judges should reconsider how due process protections are implemented. Courts should not presume jurors will follow an instruction to find guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Jurors may fully understand the burden of persuasion and seek to implement it in good faith, but their error aversions may affect how they view evidence and how they decide whether it exceeds the prosecution’s burden. As a result, jury instructions regarding burdens of proof may not be adequate to secure the values underlying due process protections. Instead, we suggest courts consider nontrial protections, like more stringent pretrial screening of criminal cases, similar to the process courts already use for civil cases. Or courts could more carefully limit what evidence gets admitted. For far too long, constitutional criminal procedure, evidence law, and trial practice have assumed jurors will impartially test a prosecution case. We call into question that assumption and suggest a different path for criminal procedure.

The error aversions we document may also affect a range of broader policy decisions that define our criminal justice system. Public policy advocates who assume the median voter will support initiatives to minimize the risk of false convictions, regardless of impact on crime control, ignore the reality that most Americans care equally about convicting the innocent and freeing the guilty.31To our knowledge, no research has examined Americans’ support for specific criminal justice and policing policies as a function of Americans’ error aversions. Givati, however, examined support for police spending as a function of greater concern about false convictions versus false acquittals and found that those more concerned about false acquittals were willing to spend more on policing. See Yehonatan Givati, Preferences for Criminal Justice Error Types: Theory and Evidence, 48 J. Legal Stud. 307, 321, 327–28 (2019). In contrast, Williamson and colleagues examined Australians’ support for police funding as a function of the same error aversions and found that those more concerned with false convictions supported greater funding of the police. See Harley Williamson, Mai Sato & Rachel Dioso-Villa, Wrongful Convictions and Erroneous Acquittals: Applying Packer’s Model to Examine Public Perceptions of Judicial Errors in Australia, Int’l J. Offender Therapy & Compar. Criminology 15 (Dec. 29, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X211066826. Voters often determine criminal justice policy through ballot measures or elections of public officials like district attorneys.32For information on the movement to accomplish criminal justice reform through such electoral efforts, see, for example, Angela J. Davis, Reimagining Prosecution: A Growing Progressive Movement, 3 UCLA Crim. Just. L. Rev. 1 (2019). Policy debates that pivot between extremes of being tough on crime versus protecting the rights of the accused overlook the largest group of voters, who worry equally about crime control and due process. Large majorities express great concern about crime but also about police use of excessive force; they support efforts to hold bad cops accountable but resist efforts to defund the police.33William Saletan, Americans Don’t Want to Defund the Police. Here’s What They Do Want., Slate (Oct. 17, 2021, 7:00 PM), https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2021/10/police-reform-polls-white-black-crime.html [perma.cc/Y28Q-H6E4]. In short, people care about public safety and fairness.

We conclude by emphasizing that despite sometimes heated legal and political rhetoric, our criminal justice system does not operate as a zero-sum game, even though in any given case the prosecution or defense wins. The public is not well-served by false dichotomies. Convicting the wrong person is not just a fairness concern but also a public safety concern. When an innocent person languishes in prison, a guilty person goes free.34For insights into the role of wrongful convictions in exposing failure to convict actual culprits, as well as convicting the innocent, see, for example, Brandon L. Garrett, Convicting the Innocent 5 (2011) (“In 45% of the 250 postconviction DNA exonerations (112 cases), the test results identified the culprit.”). Unnecessarily jailing the innocent harms the person and the community and produces no gain in public safety.35For studies finding that cash bail imposition can increase reoffending while imposing other social and sentencing harms, see, for example, Paul Heaton, Sandra Mayson & Megan Stevenson, The Downstream Consequences of Misdemeanor Pretrial Detention, 69 Stan. L. Rev. 711, 747 (2017); Will Dobbie, Jacob Goldin & Crystal S. Yang, The Effects of Pretrial Detention on Conviction, Future Crime, and Employment: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Judges, 108 Am. Econ. Rev. 201, 224–26 (2018). From bail reform, to sentencing reform, to protections against wrongful convictions, a range of proposed changes can improve both fairness and public safety.36Scholars and policymakers have been engaged in a rethinking of public safety from a broader perspective, taking into account fairness to defendants, community harm, and more. See, e.g., Phillip Atiba Goff, Elizabeth Hinton, Tracey L. Meares, Caroline Nobo Sarnoff & Tom R. Tyler, Just. Collaboratory & Ctr. for Policing Equity, Re-imagining Public Safety: Prevent Harm and Lead with the Truth (2020), https://policingequity.org/images/pdfs-doc/reports/re-imagining_public_safety_final_11.26.19.pdf [perma.cc/ZH3Q-EZNV]; Monica C. Bell, Police Reform and the Dismantling of Legal Estrangement, 126 Yale L.J. 2054 (2017); Policing Project & Just. Collaboratory, Reimagining Public Safety: First Convening Report (2021), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58a33e881b631bc60d4f8b31/t/602d826b6b3233405feabd52/1613595247852/RPS+Session+I+Report.pdf [perma.cc/9LMA-7UJG]. This reframing should be attractive to people who value due process and public safety. Our findings therefore support the view that making fairness and public safety benefits clear to the public will be crucial to the success of future criminal justice reforms.

I. The Distribution of Trial Error Aversions in the General Public

Although extremely influential in formulating jury instructions at criminal trials, Blackstone’s ratio is never explicitly stated. Jurors are not told that the law prefers to err on the side of letting the guilty go free or that all ambiguities and doubts should be resolved in favor of the accused, even if that means allowing a guilty person to go free. Rather, judges typically instruct jurors in a barebones manner that the “defendant is presumed innocent of . . . the charges” and that this presumption “is not overcome unless . . . you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the [defendant] is guilty as charged.”37See Comm. on Fed. Crim. Jury Instructions of the Seventh Cir., The William J. Bauer Pattern Criminal Jury Instructions of the Seventh Circuit 9 (2020), https://www.ca7.uscourts.gov/pattern-jury-instructions/pattern_criminal_jury_instructions_2020edition.pdf [perma.cc/6FAB-HA5N].

Given the abstract nature of this language, it is perhaps not surprising that jurors often fail to understand that the burden of production lies solely with the state and that the defendant has no obligation to put forth any evidence.38See Joel D. Lieberman, The Psychology of the Jury Instruction Process, in 1 Psychology in the Courtroom 129, 132 (Joel D. Lieberman & Daniel A. Krauss eds., 2009) (summarizing studies showing that many jurors fail to understand the presumption of innocence and allocation of burdens). Nor is it surprising that jurors vary widely in their interpretations of the level of subjective certainty required by the reasonable doubt instruction.39Id. at 133–34; see also Mandeep K. Dhami, On Measuring Quantitative Interpretations of Reasonable Doubt, 14 J. Experimental Psych. 353, 361 (2008) (“[A]ll three methods showed wide interindividual variability in interpretations of reasonable doubt . . . .”); Mandeep K. Dhami, Samantha Lundrigan & Katrin Mueller-Johnson, Instructions on Reasonable Doubt: Defining the Standard of Proof and the Juror’s Task, 21 Psych., Pub. Pol’y & L. 169, 169 (2015) (“[T]here is considerable inter-individual variability in interpretations, meaning that different people interpret RD differently . . . .”); Katrin Mueller-Johnson, Mandeep K. Dhami & Samantha Lundrigan, Effects of Judicial Instructions and Juror Characteristics on Interpretations of Beyond Reasonable Doubt, 24 Psych. Crime & L. 117, 127 (2018) (“[I]nterpretations of BRD ranged from around .5 to 1 across people . . . .”). For the Due Process Clause to consistently protect rights, it is crucial that the legal profession understand why jurors apply different thresholds for conviction and whether legal procedures can reduce this variability.

Efforts to harmonize juror interpretations of judicial instructions through linguistic simplification can produce less compliance with instructions.40Reducing conceptual complexity can increase compliance, but reducing linguistic complexity alone will likely not suffice, and reducing the amount of information given may increase noncompliance. See Chantelle M. Baguley, Blake M. McKimmie & Barbara M. Masser, Deconstructing the Simplification of Jury Instructions: How Simplifying the Features of Complexity Affects Jurors’ Application of Instructions, 41 Law & Hum. Behav. 284, 300 (2017) (“[O]ur analysis also shows that simplifying certain features of complexity unintentionally and adversely affects the punitiveness of jurors’ verdicts.”). Reducing conceptual complexity, as opposed to linguistic complexity, is more difficult because legal concepts do not usually have simpler analogs and because simplifying a concept may alter its intended meaning. Further, jury researchers agree that differences in education levels and other demographic differences cannot explain why jurors interpret and apply judicial instructions differently.41See, e.g., Joel D. Lieberman, The Utility of Scientific Jury Selection: Still Murky After 30 Years, 20 Current Directions in Psych. Sci. 48, 49 (2011) (“The effect of demographic characteristics on verdict inclinations has been investigated for a wide variety of factors, including occupation, age, socioeconomic status, ethnicity/race, and gender. However, these factors typically account for less than 2% of verdict variance when examined independently, and less than 5% when combined together.” (citations omitted)). Juror gender, however, has been found to be more predictive than other demographics “in cases involving domestic homicide and/or child or female victims.” See Dennis J. Devine & David E. Caughlin, Do They Matter? A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Individual Characteristics and Guilt Judgments, 20 Psych. Pub. Pol’y & L. 109, 124 (2014). Instead, they appear to primarily flow from differences in “legal personality,” which involves personal beliefs and attitudes pertaining to civil liberties, the interests of victims, and the rights of the accused.42Lieberman, supra note 41, at 49. In particular, differences in jurors’ levels of cynicism about the justice system and its protection of offenders and their beliefs about the frequency of criminal behavior and the efficacy of punishment translate into pro-prosecution versus pro-defense biases; these biases in turn affect how jurors weigh evidence and decide whether the evidence is sufficient for conviction.43See, e.g., Devine & Caughlin, supra note 41, at 122 (noting that juror authoritarianism and juror trust in the legal system yield “effects on juror guilt judgments large enough to have some practical significance”); Samantha Lundrigan, Mandeep K. Dhami & Katrin Mueller-Johnson, Predicting Verdicts Using Pre-trial Attitudes and Standard of Proof, 21 Legal & Criminological Psych. 95, 103 (2016) (finding that pretrial attitude measures of pro-prosecution versus pro-defense biases accounted for more than 21 percent of the variance in juror verdicts). Jurors, in short, react differently to the same judicial instructions because they bring different preconceptions and goals to the jury task.44It is important to note that jurors with different legal personalities often agree in their verdicts where the evidence in a case clearly supports guilt or a lack of guilt; in general, “extralegal” factors such as juror personality or race of the defendant tend to have their strongest effects where the evidence is most ambiguous. See, e.g., Len Lecci, Christopher Beck & Bryan Myers, Assessing Pretrial Juror Attitudes While Controlling for Order Effects: An Examination of Effect Sizes for the RLAQ, JBS, and PJAQ, 31 Am. J. Forensic Psych., no. 3, 2013, at 41, 46 (“[I]n studying the effects of pretrial bias on juror judgments, the general tendency is for evidence to carry the day. In other words, pretrial biases are most likely to exert their influence when the case is equally strong for the prosecution and the defense.” (citations omitted)).

These differences in legal personality explain why people may differ in their aversions to the two possible errors at trial: false convictions versus false acquittals. Jurors averse to false acquittals should be more skeptical of defense evidence and have a lower threshold for conviction.45See Phoebe C. Ellsworth, Some Steps Between Attitudes and Verdicts, in Inside the Juror: The Psychology of Juror Decision Making 42, 56 (Reid Hastie ed., 1993) (The “greater the [anticipated] regret the juror feels for a mistaken conviction relative to a mistaken acquittal, the higher will be his or her threshold of conviction”); Lundrigan et al., supra note 43, at 96 (“For example, a juror with a pro-prosecution bias would be expected to have a lower conviction threshold . . . than a juror with a pro-defence bias, and consequently the former would be more likely to return a guilty verdict compared with the latter.”). Likewise, to the extent that jurors believe that few defendants who reach trial have been falsely accused and thus discount the need for defendant protections, they should be less concerned with the risk of false convictions and more willing to convict. Conversely, jurors averse to false convictions should be more skeptical of prosecution evidence and should have a higher threshold for conviction.

If most jurors have legal personalities that lead to strong aversions to wrongful convictions, then we should expect juries to fulfill their duties in ways that ensure constitutionally guaranteed due process for criminal defendants: these jurors will hold the government to its high burden of proof and convict only where the proof of guilt is strong.46Those with the strongest aversions to false convictions might, however, hold the government to too high a burden and acquit those who should have been convicted under a reasonable doubt burden. If many jurors have legal personalities that result in strong aversions to wrongful acquittals, however, then we should worry that juries will not require strict proof of guilt, will not presume innocence, and will not disregard evidence such as a defendant’s criminal history that might cause them to have public safety concerns.47See, e.g., Lundrigan et al., supra note 43, at 105 (“We found that the more biased jurors are towards conviction, the lower their quantitative interpretation of [beyond a reasonable doubt].”).

In the two Sections that follow, we first survey prior research on the public’s trial error aversions and the limitations of this research. Then, we turn to our own studies, presenting a very different picture of Americans’ aversions to false convictions versus false acquittals.

A. Prior Survey Data on Trial Error Aversions

At first glance, prior research seems to support the view that a majority of Americans share legal elites’ stronger aversion to false convictions. The primary source of evidence on the public’s trial error aversions has been the General Social Survey (GSS), which is a “nationally representative survey of adults in the United States conducted since 1972.”48About the GSS, Gen. Soc. Survey, https://gss.norc.org/about-the-gss [perma.cc/F9XY-HGGV]. The GSS “collects data on contemporary American society in order to monitor and explain trends in opinions, attitudes and behaviors.”49Id. Participants are adults surveyed in face-to-face interviews, and the GSS uses multistage sampling to produce a group of respondents proportional to the population living in the continental United States.50 James A. Davis & Tom W. Smith, The NORC General Social Survey: A User’s Guide 31 (Peter V. Marsden ed., 1992). The GSS, which includes hundreds of questions on a wide range of topics, is considered “an important contributor to the statistical and scientific investigation of American society,” and has served as the basis for thousands of journal articles, books, and dissertations.51Stephen Adair, Immeasurable Differences: A Critique of the Measures of Class and Status Used in the General Social Survey, 25 Human. and Soc’y 57, 58 (2001).

The key source of data on Americans’ error aversions comes from a single question on the GSS. Since 1985, the GSS has periodically asked Americans the following question: “All systems of justice make mistakes, but which do you think is worse, to convict an innocent person, or to let a guilty person go free?”52Givati, supra note 31, at 317–18. The question on trial error aversions was included in the 1985, 1990, 1996, 2006, and 2016 iterations of the GSS. Id. at 318. Collectively, these surveys appear to show that “74 percent of Americans think that convicting an innocent person is worse than letting a guilty person go free, while 26 percent hold the opposite view.”53Id. If correct, then the American public seems to share legal elites’ stronger aversion to false convictions.

The GSS employs a forced-choice format to measure error aversions (i.e., respondents must choose one of the errors as worse than the other), and other surveys using the same measurement approach reach similar conclusions to those found on the GSS. For instance, the Cato Institute’s 2016 Criminal Justice Survey asked respondents to choose whether it would be worse to have 20,000 people in prison who are actually innocent or to have 20,000 people escape imprisonment despite being actually guilty.54 Emily Ekins, Cato Instit., Policing in America 59 (2016), https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/survey-reports/pdf/policing-in-america-august-1-2017.pdf [perma.cc/ZX25-4JLK]. Sixty percent of the respondents stated that false convictions would be worse than false acquittals.55Id. at 60.

But this forced-choice measurement approach rules out the possibility that the error of false convictions and error of false acquittals are deemed equally aversive and does not measure the relative strength of the aversions. For some topics, a binary forced-choice approach may be appropriate. For example, the approach is valuable where a researcher wants to know which of two consumer products is favored or where a mock jury researcher is studying whether juries acquit or convict.56 Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods 290 (Paul J. Lavrakas ed., 2008) (“Although useful for some survey items, the forced choice format has disadvantages. The primary disadvantage is that it can contribute to measurement errors, nonresponse errors, or both.”); Arnold Lau & Courtney Kennedy, Pew Rsch. Ctr., When Online Survey Respondents Only ‘Select Some That Apply’ 3 (2019), https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/2019/05/09/when-online-survey-respondents-only-select-some-that-apply [perma.cc/CXW9-K24V] (noting limitations of “select all that apply” questions as compared with forced-choice questions). For a discussion of the use of forced-choice surveys and their limitations in the context of personality tests, see Yue Xiao, Hongyun Liu & Hui Li, Integration of the Forced-Choice Questionnaire and the Likert Scale: A Simulation Study, Frontiers in Psych., 2017, at 1, 1 (“The model may encounter underidentification and non-convergence and the test may show low test reliability in simple test designs . . . .”). But when trying to assess the relative ranking and intensity of values or policy preferences, this approach can systematically bias results and lead to incorrect predictions about what people believe and how people will make decisions.57There is more extensive literature regarding the problem of forced choice assessments of individual preferences, particularly if “no choice” is a practically important option. For example, in consumer preferences research, where consumers do have the real-world option to not buy anything, researchers have raised concerns regarding forced-choice methodologies. See, e.g., Ravi Dhar & Itamar Simonson, The Effect of Forced Choice on Choice, 40 J. Mktg. Rsch. 146 (2003) (describing that where “in many real-world situations, buyers are not forced to choose . . . . and they have the option not to purchase at all, defer purchase, or purchase elsewhere,” then studies that fail to include “no-choice option[s]” may be “systematically biased and lead to incorrect predictions”); see also G. David Hughes, Some Confounding Effects of Forced-Choice Scales, 6 J. Mktg. Rsch. 223 (1969).

Our first inkling that the forced-choice approach to measuring error aversions may produce misleading results arose by chance in the first of a series of studies we undertook to examine how jurors perceive forensic evidence. In the first of these studies, we included two questions on error aversions.58Brandon Garrett & Gregory Mitchell, How Jurors Evaluate Fingerprint Evidence: The Relative Importance of Match Language, Method Information, and Error Acknowledgment, 10 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 484, 502 (2013) (Study 2). One question asked respondents to grade the seriousness of the criminal justice system falsely convicting an innocent person, and another question asked respondents to grade the seriousness of the criminal justice system failing to convict a guilty person.59Id. (“Participants were also asked to respond to two questions designed to measure aversions to Type I and Type II errors: ‘How serious an error is it for the criminal justice system to convict an innocent person?’ and ‘How serious an error is it for the criminal justice system to fail to convict a guilty person?’ ”). Respondents answered both questions using six-point scales, with one signifying that the error was not serious and six signifying that the error was extremely serious.60Id.All but six of the 689 persons participating in the study answered both questions, and, to our surprise, the mean rating for both errors was near the top of the scale (5.78 and 5.10, respectively, for false convictions and false acquittals), and the modal rating for both errors was six (i.e., most deemed both errors to be extremely serious).61These results have not been previously reported, but the data was collected in connection with the research reported in Garett & Mitchell, supra note 58 (data available at https://osf.io/v8zy5). The modal response is the response that “has the highest frequency of occurrence” in a data set. Rebecca M. Warner, Applied Statistics 1023 (2008). Nearly half of our sample (333 respondents, or 48 percent) gave the same rating to the two errors.62Garrett & Mitchell, supra note 58. In other words, most people rated both errors to be very serious, and many people rated the errors to be equally serious.

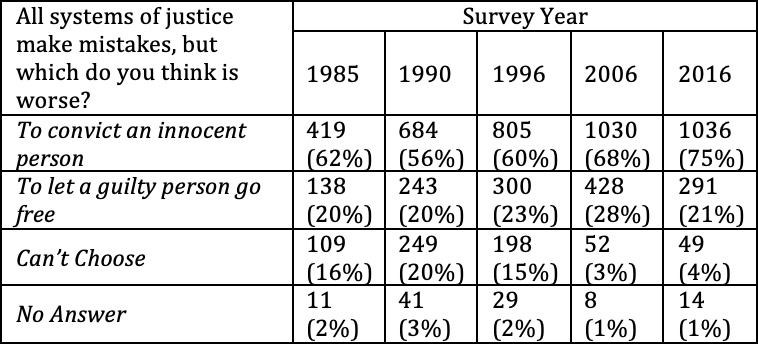

This discovery prompted a closer examination of GSS data on error aversions, and this closer look led to the realization that the forced-choice approach to measuring aversions obscures the fact that many people are strongly averse to both false convictions and false acquittals. Evidence in support of this conclusion can be found in how many respondents refused to categorize one error as more serious than the other. As shown in Table 1, every year in which the GSS has asked its forced-choice question about trial errors, many respondents indicated that they could not choose the worse error or gave no answer.63Unfortunately, the GSS does not ask additional questions that would allow researchers to determine precisely why respondents could not choose or gave no answer, nor why the percentages in these categories varied over time.

Table 1: General Social Survey Data on Trial Error Aversions

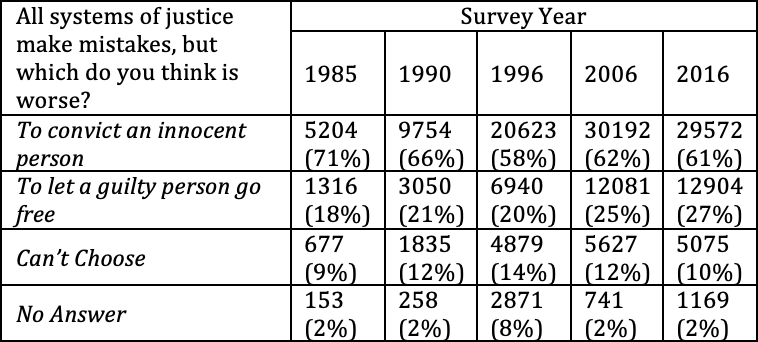

As shown in Table 2, this pattern repeats itself on the International Social Survey (ISS), the global analog to the GSS.64About ISSP, ISSP, http://www.issp.org/about-issp [perma.cc/VX2B-QHJD] (“The ISSP is a cross-national collaboration programme conducting annual surveys on diverse topics relevant to social sciences.”). The ISS asks the same forced-choice error aversion question, and again we see large numbers of respondents unwilling to choose between the errors. These data suggest that many respondents viewed the errors as equally serious and thus could not choose one error over the other.65Cf. Moulin Xiong, Richard G. Greenleaf & Jona Goldschmidt, Citizen Attitudes Toward Errors in Criminal Justice: Implications of the Declining Acceptance of Blackstone’s Ratio, 48 Int’l J. L. Crime & Just. 14, 18 (2017) (“What does selection of Can’t Choose mean in the context of the aforementioned surveys? This response may reflect conflict in the beliefs of the respondents, specifically, that Type I and Type II errors are equally problematic and constitute a miscarriage of justice, making it difficult for them to select one or the other option. It may reflect the view that it is impossible to select one or the other because there are too many factors that can impact the decision, such as the seriousness of the crime, criminal history of the defendant or other variables.”).

Table 2: International Social Survey Data on Trial Error Aversions

Furthermore, answering that false convictions were worse does not mean that those respondents considered false acquittals to be minor errors. Many people likely consider both errors to be quite serious and harmful (as data from our initial study asking about both errors showed). Data from forced-choice questions like those used on the GSS and ISS provide no insight into the relative strength of the aversions.

B. New Survey Data on Americans’ Trial Error Aversions

Given these reasons for being skeptical about the existing data on the public’s trial error aversions, we began measuring error aversions using a question that does not force respondents to choose one error over the other:

Which of the following errors at trial do you believe causes more harm to society?

- Erroneously convicting an innocent person

- Failing to convict a guilty person

- The errors are equally bad

Using this approach, we have consistently observed large numbers of respondents who rate the errors as equally harmful.

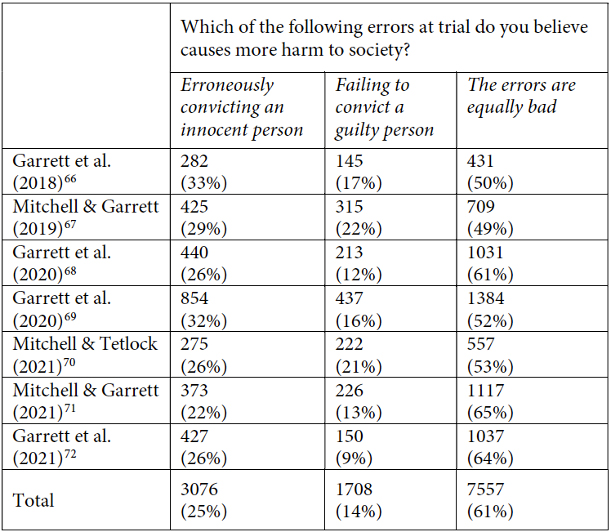

Indeed, as shown in Table 3, most Americans express equal concern about both errors and reject Blackstone’s principle, while sizeable minorities see either false convictions or false acquittals as the more serious error. These data come from national samples recruited by Qualtrics (a survey research company) to be representative of the adult population in the United States with respect to gender, race/ethnicity, age, education, income, regional location, and political identity. Over 12,000 persons have answered our error aversion question in seven different studies, and 61 percent of our respondents stated that the two errors are equally harmful. Only 25 percent viewed false convictions to be the more harmful error, as constitutional tradition holds. A large minority, 14 percent, viewed false acquittals as the more harmful error.

Table 3: Trial Error Aversions When Respondents Are Not Forced to Choose between the Errors

Footnotes for Table 3

Garrett et al. (2018);66Brandon Garrett, Gregory Mitchell & Nicholas Scurich, Comparing Categorical and Probabilistic Fingerprint Evidence, 63 J. Forensic Scis. 1712, 1714 (2018) (data available at https://osf.io/x9tm7/?view_only=6885f7881efd496c993e9b3d20ac754a). Mitchell & Garrett (2019);67Mitchell & Garrett, supra note 14, at 206. Garrett et al. (2020);68See Garrett et al., supra note 29, at 570.

Garrett et al. (2020);69These results have not been previously reported, but the data on error aversions was collected in connection with the research reported in a firearm forensics study. Brandon L. Garrett, Nicholas Scurich & William E. Crozier, Mock Jurors’ Evaluation of Firearm Examiner Testimony, 44 Law & Hum. Behav. 412 (2020) (data available at https://osf.io/qfsc3/?view_only=5f34d29b870b4adeb9f15d87dc23392a). Mitchell & Tetlock (2021);70Gregory Mitchell & Philip E. Tetlock, Are Progressives in Denial About Progress? Yes, but So Is Almost Everyone Else (2021) (unpublished manuscript) (on file with authors and available upon request) (data available at https://osf.io/pwyxa). Mitchell & Garrett (2021);71Gregory Mitchell & Brandon L. Garrett, Battling to a Draw: Defense Expert Rebuttal Can Neutralize Prosecution Fingerprint Evidence, 35 Applied Cognitive Psych. 976, 981 (2021) (data available at https://osf.io/hxr3g).

Garrett et al. (2021).72Brandon L. Garrett, William E. Crozier, Karima Modjadidi, Alice J. Liu, Karen Kafadar, Joanne Yaffe & Chad S. Dodson, Sensitizing Jurors to Eyewitness Confidence Using Reason-Based Judicial Instructions, J. Applied Rsch. Memory & Cognition (June 23, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1037/mac0000035.

To ensure that our results were not an artifact of our own measurement method, we measured error aversions in a variety of alternative ways. 73The data from these alternative measures of error aversions was collected in connection with the research reported in an eyewitness face recognition study. Adele Quigley-McBride, William Crozier, Chad S. Dodson, Jennifer Teitcher & Brandon Garrett, Face Value? How Jurors Evaluate Eyewitness Face Recognition Ability, J. Applied Rsch. Memory & Cognition (July 11, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1037/mac0000049. This data, like that summarized in Table 3, was obtained from a national sample of adults recruited by Qualtrics. First, we expanded the number of response options. Those who choose the “equally bad” category might differentiate between the errors once they were allowed to distinguish the severity of the errors. We expanded the options as follows:

Which of the following errors at trial do you believe causes more harm to society?74The information in parentheses following each response option indicates how many respondents chose each option.

- Convicting an innocent person is much more harmful (308, or 13%)

- Convicting an innocent person is somewhat more harmful (156, or 7%)

- Failing to convict a guilty person is much more harmful (192, or 8%)

- Failing to convict an innocent person is somewhat more harmful (206, or 9%)

- The two errors are equally bad (1449, or 63%)

This approach not only confirmed our prior finding that most respondents deem the errors to be of equal magnitude but it also revealed variation among those who deem one error weightier than the other. As we suspected, the forced-choice approach for measuring error aversions obscures the fact that those who rate false convictions or false acquittals as the more serious error do not all agree on the level of harm associated with that error.75Cf. Matthew D. Adler, Happiness Surveys and Public Policy: What’s the Use?, 62 Duke L.J. 1509, 1552 (2013) (“Numerous studies using standard preference data . . . have confirmed the common-sense point that different individuals often have different rankings of commodity bundles, income-leisure bundles, different degrees of risk aversion, and so forth.”).

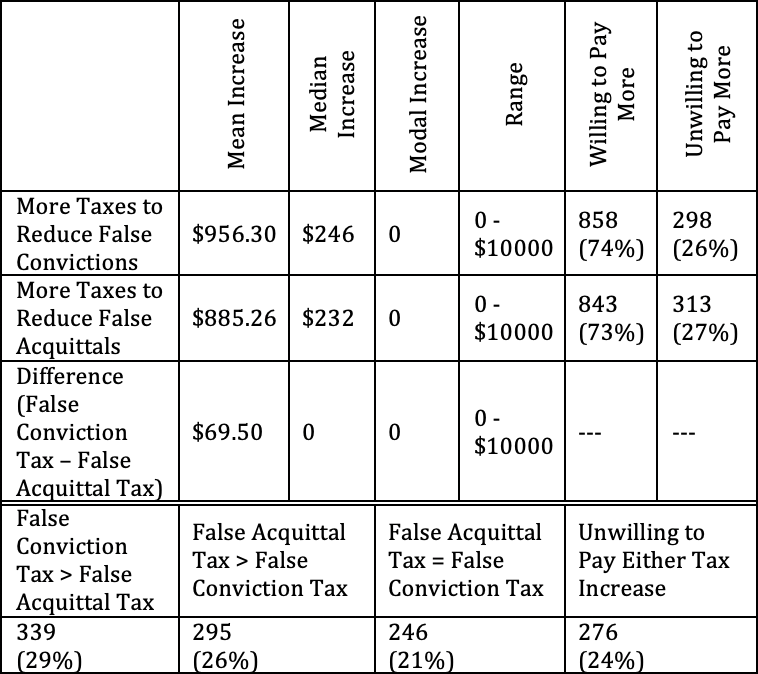

To further explore the relative magnitude of the two aversions, we utilized two different ratio-based approaches to measure error aversions: a willingness-to-pay approach and an error-distribution approach. To measure willingness-to-pay, we asked respondents how much in additional taxes they would be willing to pay each year to reduce the number of wrongly convicted innocent persons and wrongly acquitted guilty persons.76The questions in full read: (a) “How much more in taxes would you be willing to pay each year if that money were used to reduce the number of innocent persons who are wrongfully convicted by the courts?” (b) “How much more in taxes would you be willing to pay each year if that money were used to reduce the number of guilty persons who are wrongly acquitted by the courts?” For an overview of utilizing work hours to carry out such an approach, see, for example, Daniel Kahneman, Ilana Ritov & David Schkade, Economic Preferences or Attitude Expressions?: An Analysis of Dollar Responses to Public Issues, 19 J. Risk & Uncertainty 203 (1999). As shown in Table 4, more people were willing to pay more to reduce false convictions than false acquittals, and on average, people were willing to pay $69.49 more to reduce false convictions than false acquittals. Most people in our sample, however, were either unwilling to pay any tax increase to reduce either error or were willing to pay equal amounts to reduce both errors (see the last two rows of Table 4, as well as the modal responses in the first three rows). This alternative measurement method thus confirmed that most Americans care equally about the two errors, though some within this group are so sufficiently worried about both errors as to devote more tax dollars to reducing them.

Table 4: Willingness to Pay Increase in Taxes as Measure of Error Aversions

Our second ratio-measurement approach asked respondents for their ideal distribution of trial errors using the following question:

In any criminal trial, there is always the risk that the jury will reach the wrong decision. Sometimes that wrong decision results in the conviction of an innocent person, and sometimes that wrong decision results in the release of a guilty person.

Assume that each year, 100 wrong decisions are made by juries in criminal trials. If you could distribute these wrong decisions between wrongly convicting innocent persons and wrongly acquitting guilty persons, how would you distribute these two mistakes?

Type in below the number of false convictions and number of false acquittals that you would prefer each year. Your two numbers must together total up to 100.77The online survey would not allow participants to proceed unless the two numbers entered by a participant summed to 100.

False Convictions: _______

False Acquittals: _______

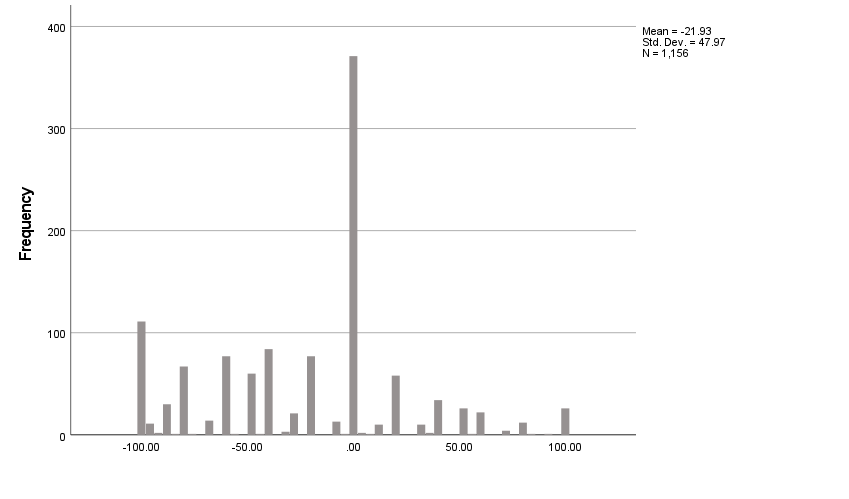

The average ratio of false convictions to false acquittals was 39:61, but the median and modal ratios were 50:50, indicating that most commonly, respondents distributed the errors equally. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of false conviction to false acquittals, where zero reflects an even distribution of errors, numbers to the left of zero reflect a preference for more false acquittals, and numbers to the right of zero reflect a preference for more false convictions.

Figure 1: Number of False Convictions Preferred Minus Number of False Acquittals Preferred

Figure 1: Number of False Convictions Preferred Minus Number of False Acquittals Preferred

Finally, we examined whether error aversions vary with the nature of the underlying wrongdoing, and we altered the wording of the question to focus respondents on their concerns about making an error when serving as a juror in a particular case. For instance, the following question asked about error aversions in a murder trial:

Imagine you are a member of a jury in a trial of a man [accused of first-degree murder. If you and your fellow jurors convict this man of murder, he will receive a sentence of life in jail without the possibility of parole].78The words in brackets varied depending on the nature of the wrongdoing and possible penalty; Table 4 specifies the cases and penalties examined. We held the gender of the defendant constant across cases, hence our use of gendered language here. The jury may make the correct decision about what actually occurred, or it may make an error and either convict an innocent man or let a guilty man go free. Which of these two possible errors would worry you more as you serve on the jury?

- I would worry much more about convicting an innocent man

- I would worry a bit more about convicting an innocent man

- I would be equally worried about both possible errors

- I would worry a bit more about letting a guilty man go free

- I would worry much more about letting a guilty man go free

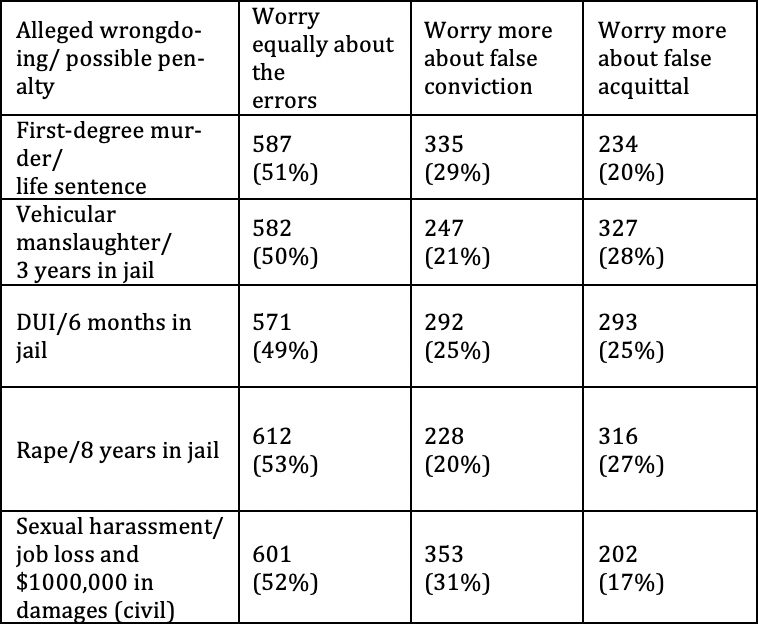

Table 5 summarizes our findings across the different cases that we examined, which ranged from first-degree murder to misdemeanor driving under the influence and which also included a civil sexual harassment claim.79These data were collected as part of a study regarding face memory ability, but not reported in that work in progress. See Quigley-McBride et al., supra note 73 (reporting results of three online studies, with 3,143, 1,156, and 3,180 participants, respectively). For this summary, we grouped together those who worried much more or a bit more about false convictions or false acquittals.

Table 5: Error Aversions across Different Types of Cases

Again, we found that most people are equally concerned about the two potential errors regardless of the wrong the defendant was accused of committing and regardless of the penalty that might be imposed on the defendant.80We did not systematically examine different penalties for each of the wrongs, so we cannot disentangle the influence of nature of the crime/tort or penalty level on responses. These results suggest that the aggregate pattern of error aversions we observe will be fairly stable across types of wrongs and penalties, but more study is necessary to determine just how stable error aversions are at the individual and group level. Further, asking respondents to imagine their concerns as jurors in a particular case did not alter the pattern that we have consistently observed.

C. Summary

In sum, across several large national samples and several different ways of measuring error aversions, we consistently find that most Americans consider false convictions and acquittals to be equally harmful and worrisome errors. Smaller groups see false convictions or false acquittals as the greater concern, but within these groups, individuals differ in the degree to which they believe the harms of one error outweigh the harms of the other.

Our results stand in stark contrast to the results obtained when error aversions are measured using a forced-choice format, an approach that our data strongly suggest leads to misleading conclusions about the distribution of error aversions among the general public. Contrary to the picture painted by surveys that assume one error ranks above the other, our surveys consistently reveal that the great majority of Americans reject Blackstone’s principle that false convictions merit greater concern than false acquittals.

II. Individual Characteristics and Error Aversions

Can we predict who will agree or disagree with Blackstone’s principle? Do those who rate the errors as equally harmful inhabit the center of the political spectrum? Do error aversions depend on one’s experiences with crime and the legal system? To answer these questions, we collected information about the demographics of our respondents, their political views, and their experiences with and beliefs about the legal system.81The results presented here come from multiple surveys, some of which asked different background questions. Accordingly, the number of respondents will vary across the analyses and tables presented. It turns out that there are significant differences between those who agree with Blackstone and those who disagree.

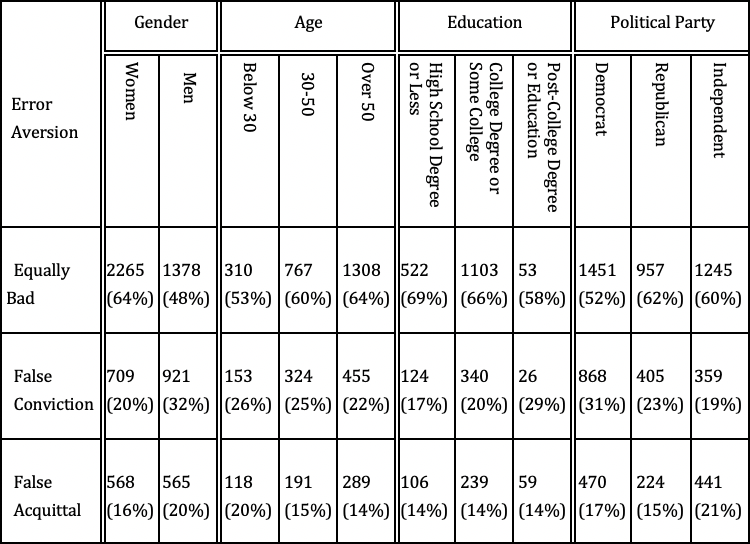

A. Demographic and Political Differences

A regression equation seeking to predict error aversions based on respondents’ self-reported age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, education, and political party preference (Democrat, Republican, or Independent) found that each of these variables, except for race/ethnicity and income, significantly improved prediction.82We employed a multinomial regression because the variable to be predicted was divided into three categories (false convictions worse, false acquittals worse, and errors equally bad). To conduct these analyses, we combined data from the studies reported in Table 3, where respondents had provided the same background information. As shown in Table 6, women were significantly more likely than men to rate false convictions and false acquittals as errors of equal harm,83A chi-square test rejected the null hypothesis that error aversions were evenly distributed among women and men (χ2(2) = 173.74, p < .001). Only a handful of respondents identified as nonbinary, agendered, or gender queer; these respondents predominantly rated both errors as equal. In an earlier study, Professor Givati wrote that “[u]sing GSS data, I find that women care less about convicting the innocent than men.” Givati, supra note 31, at 310. Our results using the expanded measure of error aversions show that most women are equally concerned about the two errors rather than less concerned about false convictions. persons under the age of 30 were less likely to equate the errors compared to older persons,84A chi-square test rejected the null hypothesis that error aversions were evenly distributed across age groups (χ2(4) = 25.07, p < .001). and those with post-college education were more likely to rate false convictions as the more serious error.85A chi-square test rejected the null hypothesis that error aversions were evenly distributed across educational groups (χ2(4) = 26.43, p < .001).

Table 6: Error Aversions by Demographic Categories and Political Party Affiliation

One might expect that conservatives would be more concerned about law and order, and thus especially sensitive to letting the guilty go free, while liberals would be more concerned about the rights of the accused and the prospect of wrongful convictions. But our results defied that simple dichotomy. A greater percentage of Democrats were most averse to false convictions, but Republicans were outnumbered by Democrats and Independents among those most averse to false acquittals. And a majority of all three groups rated both errors as equally harmful, with Republicans and Independents significantly more likely to be in this group than Democrats.86A chi-square test rejected the null hypothesis that error aversions were evenly distributed across political groups (χ2(4) = 113.53, p < .001).

The results summarized in Table 6 demonstrate that these demographic and political differences occur at the margins, but what stands out is our primary finding that the majority of Americans agree convictions of the innocent and acquittals of the guilty are equally important. Across political and demographic differences, most Americans believe both types of error equally matter, rejecting the Blackstone principle and the foundational premise of the Due Process Clause. A key question is whether this flows from experiences with the criminal justice system or, conversely, whether this correlates with different views about the criminal justice system. We turn to that question next.

B. Experiences with, and Perceptions of, the Criminal Justice System

Broad demographic and political categories do a poor job differentiating among those with different error aversions, but perhaps the source of these differences can be found in individuals’ experiences with, and perceptions of, the criminal justice system and crime. To dig deeper into the possible origins of the different error aversions, we asked a series of questions about respondents’ experiences with, and beliefs about, crime and the functioning of the criminal justice system.87This data was collected as part of the research reported in a study on fingerprint experts. Mitchell & Garrett, supra note 71. To avoid having these estimates influence error aversion responses, we asked these questions after participants answered our error aversion question.

First, to examine the relationship between error aversions and experiences with the criminal justice system, we asked respondents whether they themselves or a close family member had ever been arrested, falsely accused of a serious crime, or the victim of a serious crime. Second, to examine the relationship between error aversions and beliefs about the operation of the criminal justice system, we asked respondents to estimate the number of false convictions, false acquittals, and unsolved crimes per 100 crimes, and we asked respondents whether they believe the criminal justice system gives too much or too little attention to the interests of criminal defendants and crime victims.

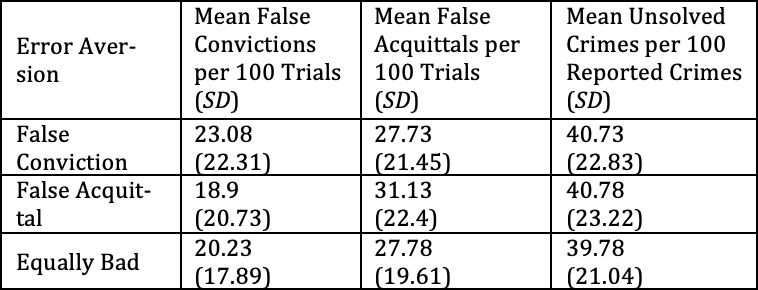

Surprisingly, different experiences with the criminal justice system did not correlate with different error aversions. Although a substantial number of our respondents reported that they or family members had been arrested or victimized, none of these experiences significantly predicted error aversions.88Of the 1716 participants in this study, 454 (27%) reported that they or a family member had been arrested, 350 (20%) reported that they or a family member had been a crime victim, and 152 (9%) reported that they or a family member had been falsely accused of a crime. But different beliefs about the functioning of the criminal justice system did correlate with differences in error aversions. Estimates of the number of false convictions, false acquittals, and unsolved crimes, as well as perceptions that the criminal justice system attends too much or too little to the interests of defendants or victims, all significantly or marginally predicted error aversions.89A multinomial regression predicting whether respondents stated that false convictions were worse, false acquittals were worse, or that the errors were equally bad found that estimates of false acquittals per 100 trials and views about the interests of criminal defendants and crime victims were associated with error aversions below the usual .05 statistical significance level. Estimates of false convictions were associated with error aversions at the p = .09 level and estimates of unsolved crimes were associated with error aversions at the p = .05 level.

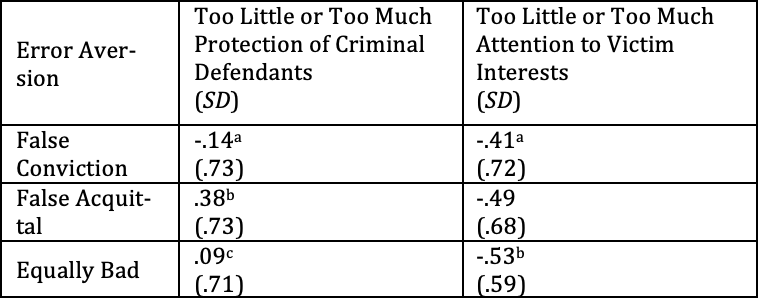

Examining these specific beliefs in more detail sheds further light on the possible origins of the different error aversions. As shown in Table 7, when it comes to beliefs about the treatment of criminal defendants, those who worry most about false convictions believe that the law gives too little protection to criminal defendants, those who worry most about false acquittals believe the law gives too much protection to criminal defendants, and those who worry about both errors largely believe the law gives about the right amount of protection to criminal defendants. All three groups believe the law gives too little attention to the interests of crime victims, but the only significant gap in beliefs was between those most worried about false convictions and those who worry about both errors.90Participants were asked whether the law gives too little (scored as -1), too much (scored as 1), or about the right amount of protection to criminal defendants (scored as 0), and participants were asked whether the law gives too little (-1), too much (1), or about the right amount of attention to victim interests (0). The mean scores in Table 7 below 0 indicate too little protection or attention, and mean scores above 0 indicate too much protection or too much attention. Mean scores in Table 7 with different superscripts were significantly different from one another at the .05 level, as determined by a post hoc Tukey test.

Table 7: Participant Beliefs about the Interests of the Accused and Victims

Although estimates of the error rates improved prediction of which error aversion individuals would hold when those estimates were added to a regression equation, most of the observed differences in estimates across the error aversion groups did not rise to the level of statistically significant differences when considered on their own. As shown in Table 8, those most concerned about false convictions gave higher estimates of the number of false convictions and lower estimates of the number of false acquittals than those most concerned with false acquittals. Those equally concerned about the two errors gave estimates that fell between the other groups’ estimates. Only the higher estimate of false convictions given by those most averse to false convictions differed significantly from the estimates of other groups.91The difference in each group’s mean estimates were tested using a post hoc Tukey test. The mean estimate of false convictions given by those most averse to false convictions was significantly different from the estimate given by those most averse to false acquittals (p = .03) and those equally averse to the errors (p = .04). The difference in estimates by those averse to false acquittals and those equally averse to the errors was not statistically significant. With regard to estimates of the number of false acquittals, the difference in estimates given by those most averse to false acquittals was marginally significant when compared to the estimates given by those equally averse to the errors (p = .067). No other comparisons were marginally or statistically significant. Interestingly, all error aversion groups gave, on average, similar estimates of the number of unsolved crimes, and all three groups estimated false acquittals to be higher than false convictions.

Table 8: Participant Estimated Error Rates and Unsolved Crime Rates by Error Versions

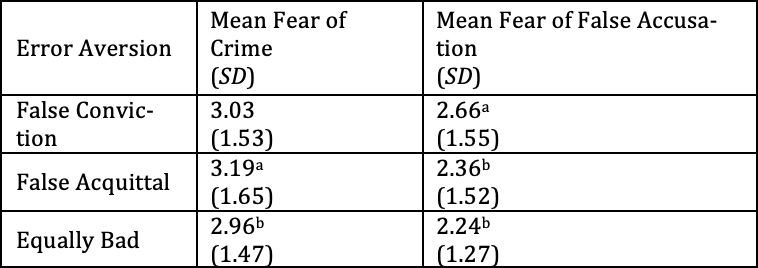

Finally, we asked respondents how often they worried that they or a family member would be a victim of a crime or falsely accused of a crime. Both worries significantly predicted error aversions.92A multinomial regression predicting whether respondents stated that false convictions were worse, false acquittals were worse, or that the errors were equally bad found that fear of crime and fear of false accusations were both associated with error aversions below the usual .05 statistical significance level. As shown in Table 9, those who worried most about false acquittals also worried more about being a crime victim than those who saw the errors as equally bad, and those who worried most about false convictions worried more about being falsely accused of a crime compared to those holding other error aversions.93Participants were asked to rate how frequently they worry about being a victim of crime and about being falsely accused of a crime on a 1 (never worry about this possibility) to 6 (worry about this possibility on a daily basis) scale. Thus, higher scores in Table 9 reflect greater worry. Mean scores in Table 9 with different superscripts were significantly different from one another at the .05 level, as determined by a post hoc Tukey test.

Table 9: Participant Fears of Crime and False Accusations of Committing a Crime

By tying the demographic and system-perception portraits together, we can paint a richer portrait of the persons who hold the different error aversions. Those who weigh false convictions more heavily tend to be those who are highly educated, male Democrats who believe that the law does not provide adequate protections for criminal defendants or that the false conviction rate is relatively high. Those who weigh false acquittals more heavily tend to be those who believe the false conviction rate is relatively low and that the law gives too much protection to defendants and too little attention to the interests of victims. Those who weigh the errors equally tend to be Independents over the age of 30 (especially female Independents over the age of 50) who worry about being a crime victim or believe that the law does a good job protecting the rights of criminal defendants but not with respect to the interests of victims.

Notwithstanding these differentiating factors, it is important not to overstate the identifiable differences among those who hold different error aversions. Indeed, wagering that a randomly chosen American is more likely to see false convictions and false acquittals as equally bad errors would, over time, be the smart bet. In our samples, most Democrats and Republicans fell into this middle ground category, as did persons of all ages, races, and ethnicities. While it is true that more women than men fell into this middle ground category, almost half of the men in our samples fell into this category too.

Thus, our detailed analyses of the characteristics of the people who express different error aversions leave us with an important takeaway: large numbers of Americans across a range of demographic and ideological differences share the view that avoiding convictions of the innocent and acquittals of the guilty are equally important goals for the law to have. As we discuss next, these findings have important implications for what happens at trial.

III. Juror Behavior and Error Aversions

A number of prior studies have found that the legal personalities associated with pro-prosecution versus pro-defense biases predict juror behavior in mock trials.94See, e.g., Len Lecci & Bryan Myers, Individual Differences in Attitudes Relevant to Juror Decision Making: Development and Validation of the Pretrial Juror Attitude Questionnaire (PJAQ), 38 J. Applied Soc. Psych. 2010, 2028 (2008) (“Our findings suggest that attitudes relating to a tendency to convict, confidence in the judicial system, cynicism toward the defense, racial bias, beliefs regarding the innate quality of criminal behavior, and the belief that individuals do not receive equal protection under the law (i.e., social justice) are relevant factors in how final legal judgments are reached.”); Len B. Lecci & Bryan Myers, Predicting Guilt Judgments and Verdict Change Using a Measure of Pretrial Bias in a Videotaped Mock Trial with Deliberating Jurors, 15 Psych., Crime & L. 619, 628 (2009) (“The present study demonstrates the predictive validity of the PJAQ [measuring pro-prosecution vs. pro-defense bias] using ecologically valid stimuli (e.g. realistic trial videotape) and legal procedures (e.g. jury deliberation).”); Lecci et al., supra note 44, at 50–52 (finding that three alternative measures of legal personality predicted verdict tendencies); Lundrigan et al., supra note 43, at 105 (“We found that the more biased jurors are towards conviction, the lower their quantitative interpretation of [the beyond a reasonable doubt instruction].”); Lisa L. Smith & Ray Bull, Validation of the Factor Structure and Predictive Validity of the Forensic Evidence Evaluation Bias Scale for Robbery and Sexual Assault Trial Scenarios, 20 Psych., Crime & L. 450, 452 (2014) (showing that jurors predisposed to favor the prosecution rated the prosecution’s DNA evidence more favorably). But does the aspect of legal personality that we focus on—trial error aversions—also predict juror behavior? Across many different studies involving several thousand jury-eligible adults, we find that jurors’ error aversions do predict how individuals will analyze and weigh evidence to reach a decision on conviction or acquittal. We first describe our findings on the conviction rates associated with the different error aversions, and then we develop two possible overlapping explanations for these findings.

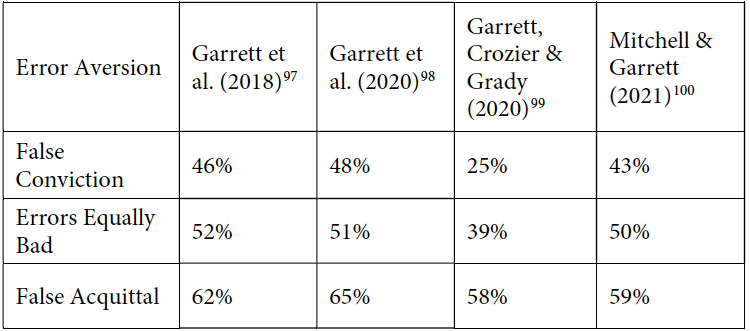

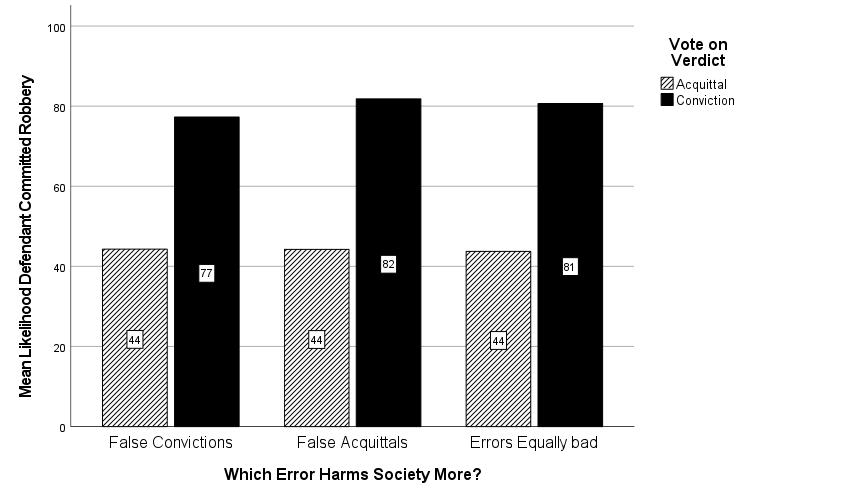

A. Error Aversions and Conviction Rates

A striking demonstration of the importance of error aversions can be seen in a comparison of conviction rates across the groups. Table 10 presents the conviction rates of the three error aversion groups from our mock juror studies in which participants were asked to vote for conviction or acquittal:95In these studies, we randomly assigned participants to different trials in which they would be exposed to different types of evidence in support of the prosecution or defense. Each mock juror participated in only one trial, and mock jurors did not deliberate before providing their responses (for additional details, please consult the studies cited in Table 10). To ensure that persons with one particular error aversion were not by chance consistently assigned to trials in which the evidence of guilt was weak or strong, we examined the distribution of participants’ error aversions across the trials and found that none of the error aversion types was overrepresented in any particular trial (i.e., there were no significant differences in the percentage of mock jurors holding the different error aversions across the trials). those most worried about false convictions are consistently less prone to convict defendants, while those most worried about false acquittals are more prone to convict, and those who worried equally about the two errors consistently exhibit conviction rates between the two extremes. Consistent with these differences in conviction proneness, we also observe that those most averse to false acquittals rate the prosecution’s evidence against the defendant to be stronger than those who equate the errors or those who worry more about false convictions, and this group is more trusting of the prosecution’s forensic evidence and more skeptical of the defense’s evidence.96See Garrett et al., supra note 28, at 1203 (“[P]eople who were more concerned about failing to convict a guilty person were more likely to vote guilty, believe the case was stronger, have a higher opinion of the reliability of voice and fingerprint evidence, and believe more people brought to criminal trial are guilty . . . .”); Mitchell & Garrett, supra note 14, at 206 (“[T]hose with stronger aversions to false acquittals versus false convictions gave more weight to the fingerprint evidence regardless of experimental condition . . . .”); Mitchell & Garrett, supra note 71, at 982–84 (discussing greater skepticism to a fingerprint expert for the defense among those most concerned about false acquittals).

Table 10: Conviction Rates by Error Aversion

Footnotes for Table 10:

Garrett et al. (2018);97These results have not been previously disclosed, but the data were collected in connection with the research reported in a study of categorical and probabilistic fingerprint evidence. Garrett et al., supra note 66. Garrett et al. (2020);98Garrett et al., supra note 29, at 570. Garrett, Crozier & Grady (2020);99Garrett et al., supra note 28, at 1204 tbl.2. Mitchell & Garrett (2021).100These results have not been previously disclosed, but the data were collected in connection with the research reported in a study on trends in progress among progressives. Mitchell & Tetlock, supra note 70.

Jurors’ trial error aversions, in short, are good proxies for pro-prosecution versus pro-defense biases that potential jurors bring into the courtroom. Those more concerned about false convictions will be more accepting of defense evidence and more skeptical of the state’s evidence, while those more concerned about false acquittals will be more likely to exhibit the opposite tendencies.101Our evidence strongly suggests that error aversions affect how jurors analyze and weigh evidence, but we also have some evidence suggesting that error aversions affect the level of subjective certainty required for conviction. In particular, we found in one study that error aversions affected receptivity to prosecution evidence and the level of subjective certainty about guilt needed for jurors to vote for conviction. Those most concerned about false convictions rated the prosecution’s case as weaker and required greater subjective certainty that the defendant committed the crime before voting for conviction (on average, those who worried about false acquittals voted to convict once they believed it was 71 percent likely the defendant committed the crime, whereas those worried about false convictions voted to convict once they believed it was 81 percent likely the defendant committed the crime) (based on data from Mitchell & Garrett, supra note 14). In another study, however, we found smaller differences in the level of subjective certainty required for conviction (on average, all of the error aversion groups voted for conviction only once the likelihood of guilt was approximately 80 percent), but those who worried more about false acquittals viewed the prosecution’s case as much stronger than those who worried more about false convictions (based on data from Mitchell & Garrett, supra note 71). In other words, in trials in this study, it was harder to convince those averse to false convictions of the defendant’s guilt and easier to convince those averse to false acquittals of the defendant’s guilt, but the groups had similar subjective certainty thresholds for voting to convict.

B. Evidence Skepticism or Burden of Proof Adjustments?

The differences in conviction rates we observe across the error aversion groups could be the product of two mechanisms: (1) an evidence skepticism effect, in which false-conviction avoidant jurors are more receptive to pro-defense evidence and arguments, and false-acquittal avoidant jurors are more receptive to pro-prosecution evidence and arguments, or (2) a burden of proof adjustment effect, in which jurors adjust their subjective threshold to convict up or down depending on which error they seek to avoid.