Discovery as Regulation

This article develops an approach to discovery that is grounded in regulatory theory and administrative subpoena power. The conventional judicial and scholarly view about discovery is that it promotes fair and accurate outcomes and nudges the parties toward settlement. While commonly held, however, this belief is increasingly outdated and suffers from limitations. Among them, it has generated endless controversy about the problem of discovery costs. Indeed, a growing chorus of scholars and courts has offered an avalanche of reforms, from cost shifting and bespoke discovery contracts to outright elimination. Recently, Judge Thomas Hardiman quipped that if he had absolute power, he would abolish discovery for cases involving less than $500,000. These debates, however, are at a standstill, and existing scholarship offers incomplete treatment of discovery theory that might move debates forward.

The core insight of the project is that in the private-enforcement context—where Congress deliberately employs private litigants as the main method of statutory enforcement—there is a surprisingly strong case that our current discovery system should be understood in part as serving regulatory goals analogous to administrative subpoena power. That is, discovery here can be seen as an extension of the subpoena power that agencies like the SEC, FTC, and EPA possess and is the lynchpin of a system that depends on private litigants to enforce our most important statutes. By forcing parties to disclose large amounts of information, discovery deters harm and, most importantly, shapes industry-wide practices and the primary behavior of regulated entities. This approach has a vast array of implications for the scope of discovery as well as the debate over costs. Scholars and courts should thus grapple with the consequences of what I call “regulatory discovery” for the entire legal system.

Introduction

Discovery is the backbone of American litigation and sits at the center of a constellation of procedural doctrines. It has shaped pleading standards, qualified immunity, and summary judgment jurisprudence and, as a practical matter, determines settlement negotiations, case outcomes, and the prevalence of trials.1John H. Langbein, The Disappearance of Civil Trial in the United States, 122 Yale L.J. 522, 526 (2012). Across a range of contexts, from civil rights to antitrust and employment claims, discovery is often outcome determinative. Perhaps because of its centrality in the system, no single procedure generates more controversy. Critics cast discovery as unconstrained, burdensome, overly costly, intrusive, and “nuts.”2See Frank H. Easterbrook, Discovery as Abuse, 69 B.U. L. Rev. 635, 637 (1989); Martin H. Redish & Colleen McNamara, Back to the Future: Discovery Cost Allocation and Modern Procedural Theory, 79 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 773, 774 (2011); Stephen N. Subrin, Discovery in Global Perspective: Are We Nuts?, 52 DePaul L. Rev. 299, 300 (2002). Supporters, by contrast, argue that complaints about discovery costs are empirically unproven and that discovery provides “public benefits.”3See Linda S. Mullenix, The Pervasive Myth of Pervasive Discovery Abuse: The Sequel, 39 B.C. L. Rev. 683, 684–85 (1998). See generally Stephen B. Burbank & Sean Farhang, Rights and Retrenchment: The Counterrevolution Against Federal Litigation (2017). A growing chorus of commentators from both camps and even courts has offered an avalanche of reforms ranging from cost shifting and bespoke discovery contracts to outright abolition.4See, e.g., Seth Katsuya Endo, Discovery Hydraulics, 52 U.C. Davis. L. Rev. 1317 (2019); Richard L. Marcus, Discovery Containment Redux, 39 B.C. L. Rev. 747 (1998). But despite such offers, existing scholarship on discovery theory, to the extent it might serve as a guide to those reforms, is incomplete. Addressing discovery’s fundamental underpinning is essential to any clear-eyed assessment of proposed changes. The resulting challenge is apparent: How can we rationalize our discovery system and the core purposes it serves?

This Article tackles the discovery morass with the goal of building a firm theoretical footing for parts of the discovery system. My most basic aim is to complement discovery’s traditional foundations in principles of fairness, equality, and settlement with a reconceptualization that draws on regulatory theory and administrative subpoena power. With a better understanding of how discovery could and should work, I hope to then reassess our most important discovery doctrines and scholarly debates in a fuller and more helpful light. The Article thus undertakes the following two goals, among many others:

First, it aspires to clarify the burdens of a current obsession with discovery costs—including the judicial creation of satellite doctrines that close access to court, like qualified immunity and higher pleading standards. While the Supreme Court dodges deeper questions about discovery, it often focuses on the back end of the system—its costs. This dearth of theory and constitutional analysis has atrophied discovery discourse. From the Supreme Court’s decisions to raise pleading standards in Twombly and Iqbal, to the attempt to protect police officers from time-consuming depositions, discovery costs have become a justification for restrictive procedure. But tethering discovery to other doctrines like pleading and qualified immunity is potentially destabilizing. It means that as Advisory Committee amendments or technological changes like machine learning5See David Freeman Engstrom & Jonah B. Gelbach, Legal Tech, Civil Procedure, and the Future of American Adversarialism, 169 U. Pa. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2020) (manuscript at 30–41) (on file with the Michigan Law Review). potentially reduce discovery costs, discovery-dependent doctrines should immediately adjust: Twombly and Iqbal would be redundant; rules that encourage settlement unnecessary; qualified immunity obsolete; and even “rigorous” policing of class actions outdated. Although this cascading effect is logically necessary, courts are likely to ignore the consequences and leave in place outdated doctrines.

Second, the Article offers a theoretical structure and new vocabulary to move debates over discovery forward into new territory—that is to say, more productive discussions that engage with the ultimate goals of the system and whether the rules are serving those goals. When it comes to discovery, courts often glide by underlying theories, embracing the simplified view that discovery can be justified because a full exchange of information results in a fair and accurate resolution of a dispute, promotes the ends of equal justice,6See Wayne D. Brazil, The Adversary Character of Civil Discovery: A Critique and Proposals for Change, 31 Vand. L. Rev. 1295, 1302 (1978); infra notes 94–98 and accompanying text. and ameliorates asymmetries between one-shot plaintiffs and repeat player defendants.7See Lawrence B. Solum, Procedural Justice, 78 S. Cal. L. Rev. 181, 287 (2004); infra notes 99–107 and accompanying text. Moreover, by forcing the parties to reveal all their arguments and evidence, discovery narrows issues for trial and nudges the parties toward settlement.8See Robert D. Cooter & Daniel L. Rubinfeld, An Economic Model of Legal Discovery, 23 J. Legal Stud. 435, 436 (1994); Langbein, supra note 1, at 533; Stephen C. Yeazell, Getting What We Asked For, Getting What We Paid For, and Not Liking What We Got: The Vanishing Civil Trial, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 943, 950–54 (2004); infra notes 108–119 and accompanying text. The main drafter of the discovery rules, Edson Sunderland, argued that broad discovery would be a boon because it would make trials unnecessary. Edson R. Sunderland, Improving the Administration of Civil Justice, in 167 Annals Am. Acad. Pol. & Soc. Sci. 60, 75 (1933); see also Stephen N. Subrin, Fishing Expeditions Allowed: The Historical Background of the 1938 Federal Discovery Rules, 39 B.C. L. Rev. 691, 691, 697 (1998). But this fairness-accuracy-settlement mantra suffers from significant limitations because it overlooks the role that discovery plays in private-enforcement cases. Taking that role into account transforms the ultimate goals of parts of the system and offers a dose of comfort: within the American private-enforcement scheme—one that relies on private litigants to enforce important statutes—our discovery rules make sense and offer an array of benefits.

At the center of the Article is a theory of private discovery that addresses these questions with a regulatory model grounded in administrative power.9Some scholars have previously argued in favor of—but not fully explored—this justification. See, e.g., Burbank & Farhang, supra note 3, at 70 (“Discovery under the 1938 Federal Rules conferred on private litigants and their attorneys the functional equivalent of administrative subpoena power.” (footnote omitted)); Stephen B. Burbank, Proportionality and the Social Benefits of Discovery: Out of Sight and Out of Mind?, 34 Rev. Litig. 647, 651–54 (2015) (noting the agency subpoena’s strength as a regulatory tool and arguing that to ensure “proportionality [does not] become a deregulatory tool . . . judges must resist the temptation to privilege . . . private over public interests” in discovery rulings); Paul D. Carrington, Renovating Discovery, 49 Ala. L. Rev. 51, 54 (1997) (“Private litigants do in America much of what is done in other industrial states by public officers working within an administrative bureaucracy.”); Patrick Higginbotham, Foreword, 49 Ala. L. Rev. 1, 4–5 (1997) (“Calibration of discovery is calibration of the level of enforcement of the social policy set by Congress.”). However, this theory and its many implications have not been fully developed. A long and rich literature has described how the United States depends largely on private plaintiffs to enforce important statutes in contexts like employment, environmental protection, antitrust, and civil rights.10See infra notes 123–129 and accompanying text; see also Robert A. Kagan, Adversarial Legalism: The American Way of Law 10 (2nd ed. 2019) (emphasizing litigant participation as central to the “American way of law”); Nora Freeman Engstrom, When Cars Crash: The Automobile’s Tort Law Legacy, 53 Wake Forest L. Rev. 293, 305–08 (2018) (discussing the “much larger regulatory fabric,” enforced by private causes of action, around auto claims); J. Maria Glover, The Structural Role of Private Enforcement Mechanisms in Public Law, 53 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1137, 1141 (2012) (arguing that private enforcement mechanisms are “often an institutional feature of our public law”). In these cases, private lawsuits become a regulatory tool and the legal system transforms from one where “one citizen can seek redress from another in an orderly fashion,”11Jack H. Friedenthal, Secrecy in Civil Litigation: Discovery and Party Agreements, 9 J.L. & Pol’y 67, 69 (2000). into one where citizens or groups of citizens can enforce the law for systemic regulatory purposes.12This is, of course, a contested view rejected by eminent scholars. For example, Martin Redish challenges the legitimacy of such a view and argues that litigation cannot have a regulatory role, especially through procedural vehicles like class actions, without violating the Rules Enabling Act. See, e.g., Martin H. Redish, Wholesale Justice: Constitutional Democracy and the Problem of the Class Action Lawsuit (2009). I set these debates aside here. I extend this literature to argue that in a lawsuit-as-regulation system, discovery is the lynchpin of private enforcement. By forcing parties to disclose large amounts of information, the discovery system deters harmful behavior, structures the regularized production of information within corporations, and, most importantly, shapes the primary behavior of regulated entities.13Among others, I draw on three literatures that have produced related insights: First, research finding that discovery can unearth otherwise-hidden information on corporate misconduct and lead to internal corporate reforms. See, e.g., Érica Gorga & Michael Halberstam, Litigation Discovery and Corporate Governance: The Missing Story About the “Genius of American Corporate Law,” 63 Emory L.J. 1383 (2014) (arguing that discovery has shaped corporate law); Joanna C. Schwartz, Introspection Through Litigation, 90 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1055 (2015) [hereinafter Schwartz, Introspection Through Litigation](arguing that litigation allows companies to engage in “introspection” about internal behavior that would otherwise go unrecognized). Scholars have studied this phenomenon in several areas, including medical malpractice, see Tom Baker, The Medical Malpractice Myth (2005); Joanna C. Schwartz, A Dose of Reality for Medical Malpractice Reform, 88 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1224 (2013) [hereinafter Schwartz, A Dose of Reality]; gun litigation, see Timothy D. Lytton, Using Tort Litigation to Enhance Regulatory Policy Making: Evaluating Climate-Change Litigation in Light of Lessons from Gun-Industry and Clergy-Sexual-Abuse Lawsuits, 86 Tex. L. Rev. 1837 (2008); Wendy Wagner, When All Else Fails: Regulating Risky Products Through Tort Litigation, 95 Geo. L.J. 693 (2007); clergy-sexual-abuse litigation, see Lytton, supra; and breast-implant litigation, see Wagner supra.

Second, the long line of works that describe litigation more generally as a form of regulation. See, e.g., Sean Farhang, The Litigation State: Public Regulation and Private Lawsuits in the U.S. 60, 64–65 (2010); Pamela H. Bucy, Private Justice, 76 S. Cal. L. Rev. 1 (2002); Glover, supra note 10; Schwartz, Introspection Through Litigation, supra; Michael Selmi, Public vs. Private Enforcement of Civil Rights: The Case of Housing and Employment, 45 UCLA L. Rev. 1401 (1998); Matthew C. Stephenson, Public Regulation of Private Enforcement: The Case for Expanding the Role of Administrative Agencies, 91 Va. L. Rev. 93 (2005).

Finally, work in the intersection of torts and civil procedure that focuses on litigation’s public benefits in a variety of tort-related contexts. See Engstrom, supra note 10, at 328–35 (auto); Robert L. Rabin, Poking Holes in the Fabric of Tort: A Comment, 56 DePaul L. Rev. 293, 302 (2007) (asbestos, tobacco, and medical instruments). See generally Alexandra Lahav, In Praise of Litigation (2017). Discovery therefore serves an important purpose in a legal system that relies on private litigants to enforce the law.

While this view of discovery-as-regulation has been discussed by some scholars, the Article at its core pushes the theory forward and fully develops it by focusing on the analogy to administrative subpoena power.14Steve Burbank and Sean Farhang have previously noted this resemblance. Burbank & Farhang, supra note 3, at 70 (“Discovery under the 1938 Federal Rules conferred on private litigants and their attorneys the functional equivalent of administrative subpoena power.” (citations omitted)); Burbank, supra note 9, at 651–54. But the analogy remains underexplored, and this Article is the first to undertake a comprehensive comparison between private discovery and administrative subpoena power. That power is the absolute “backbone of an administrative agency’s effectiveness,” because it gives agencies “the ability to investigate rapidly the activities of entities within the agency’s jurisdiction.”15Jack W. Campbell IV, Revoking the “Fishing License:” Recent Decisions Place Unwarranted Restrictions on Administrative Agencies’ Power to Subpoena Personal Financial Records, 49 Vand. L. Rev. 395, 396 (1996) (footnote omitted). Agencies can issue ex parte subpoenas for vast amounts of regulated entities’ information.16See infra Section III.B.1. The SEC, for example, routinely requests burdensome productions of financial documents.17See infra note 182 and accompanying text. The FTC demands thousands of pages related to any potential merger. The EPA, too, makes regular inquiries into environmental polluters. Civil discovery’s broad scope is partly an extension of this power. Congress enacted a wide variety of broad statutes and has delegated enforcement to private plaintiffs rather than agencies.18See generally Farhang, supra note 13. In order for these statutes to succeed, just as the FTC, EPA, and SEC possess subpoena powers, so too do plaintiffs need powerful discovery tools. Beyond individual cases, discovery promotes regulatory goals by influencing how companies run internal investigations, how management structures operations, and how regulators formulate new rules.19See Gorga & Halberstam, supra note 13, at 1453–54. To be sure, plaintiffs lack the democratic and public legitimacy of agency officials, so their private tools cannot, and do not, fully mirror agency power. But I argue extensively that, for many reasons—including the distorted incentives of public enforcers and the fact that Congress’s choice to arm private plaintiffs with this discovery power confers a measure of democratic legitimacy in itself—this difference does not weaken the legitimacy or effect of regulatory discovery.

Conceptualizing discovery as a regulatory tool should transform our current understanding of litigation as regulation—and also changes the problem of discovery costs into a comparative question. Whether discovery costs are too high should depend less on a case’s amount in controversy and more on whether the case generates proportional regulatory benefits and fewer costs than a comparable agency investigation. In discovery disputes, courts and litigants should explicitly consider this comparison. This is not to say that agency costs are optimal, but only that an agency investigation is the conceptual alternative to private enforcement and is therefore a good point of reference. Costs, in this sense, have little to do with the individual interests of litigants. They instead must take into account the systemic benefits of enforcing a statute in a context where Congress chose private plaintiffs to investigate wrongdoing. Thus, complaints about discovery costs must grapple with the burdens of agency subpoena powers in the first place. Discovery is an alternative to—and an outsourced version of—administrative regulation.

The bulk of the Article discusses the intricacies of regulatory discovery, but a brief example demonstrates its implications. In a 2005 case against Disney, plaintiff-shareholders claimed that the company had corruptly awarded $140 million dollars to an outgoing executive.20Id. at 1401; see also In re Walt Disney Co. Derivative Litig., 907 A.2d 693 (Del. Ch. 2005), aff’d, 906 A.2d 27 (Del. 2006). Discovery in the case was substantial: 9,000 pages of transcripts, extensive business records, and detailed private correspondence. Under a traditional understanding of discovery—the fairness-accuracy-settlement view—all of this information exchange was a waste because the court ultimately found (at trial) that Disney was not liable.21See Gorga & Halberstam, supra note 13, at 1402. But take a regulatory and systemic view and things look very different. Disney’s board, along with a series of competitors and peers, completely reformed their governance structures based on documents produced in discovery.22Id. at 1403. This extensive information also allowed the court to “articulate[] new standards of fiduciary duty,” gave lawyers new tools “to get their clients to accept better conduct and procedures,” and even informed new SEC regulations.23Id. at 1427 (citations omitted). Discovery, in other words, regulated system-wide corporate behavior.

With this discovery theory in view, the Article then offers a few primary contributions. To begin, whereas discovery scholarship focuses on individual issues, such as costs or the language of Rule 26, this Article is the first to tie background justifications together into a single theoretical framework—one that can inform each court’s discovery analysis. This discussion of theory highlights discovery’s relationship to values like accuracy, regulation, and fairness. This also allows the Article to make a normative case for how courts should carry out discovery inquiries. Discovery is a plural device with multiple justifications and both individual and systemic implications. For example, whereas fairness and equality theories sound in individual rights, regulatory discovery, by contrast, is only systemic. So in private-enforcement cases, courts should err on the side of broad discovery by interpreting “proportionality” in relation not only to the needs of the specific case but also to the needs of the relevant statutory regime and industry. Moreover, the breadth of discovery should be related to whether the statutory regime depends largely, somewhat, or only scarcely, on private enforcement. The more a regime depends on private enforcement, the broader discovery should be, and vice versa. The Article otherwise adds to an emerging literature on the fruitful interaction between administrative law and civil procedure.24See, e.g., David Freeman Engstrom, Agencies as Litigation Gatekeepers, 123 Yale L.J. 616 (2013); Lumen N. Mulligan & Glen Staszewski, The Supreme Court’s Regulation of Civil Procedure: Lessons from Administrative Law, 59 UCLA L. Rev. 1188 (2012); David L. Noll, MDL as Public Administration, 118 Mich. L. Rev. 403 (2019); Michael Sant’Ambrogio & Adam S. Zimmerman, Inside the Agency Class Action, 126 Yale L.J. 1634 (2017).

Additionally, the Article develops a better vocabulary for describing regulatory discovery’s implications, so that public discussions can be better informed. Just in the past year, arguments about discovery have gone mainstream. Judges Hardiman and Thapar recently proposed to abolish discovery for cases “worth less than $500,000.”25Debra Cassens Weiss, Judge on Trump’s Supreme Court Short List Proposes Discovery Ban for Cases Worth Less than 0K, A.B.A J. (Dec. 10, 2018, 8:15 AM), http://www.abajournal.com/news/article/judge_on_trumps_supreme_court_shortlist_proposes_discovery_ban_for_cases_wo [https://perma.cc/4XJ6-N8FH]. Judge Hardiman lamented the loss of jury trials, too. But these critiques overlook many of discovery’s core purposes. With an institutional view in mind, it’s clear that discovery can limit trials in order to save costs and avoid the burden of impaneling a jury. Similarly, under regulatory discovery, the amount in controversy may be irrelevant—what matters more is whether a plaintiff is enforcing a statute that depends on private claims. Cases worth less than $500,000 can nonetheless have significant positive spillovers on the law and regulated industries by spurring deterrence, corporate reforms, and better regulation by agencies.26Cf. Stephen B. Burbank & Stephen N. Subrin, Litigation and Democracy: Restoring a Realistic Prospect of Trial, 46 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 399, 409, 411 (2011) (proposing categorical restrictions on discovery “for ‘simple’ cases”—defined by amount in controversy—but excluding private enforcement cases, where “broader discovery . . . may be necessary for adequate enforcement”). For instance, documents and depositions in the seminal sexual harassment case Faragher v. City of Boca Raton27524 U.S. 775 (1998).—with an amount in controversy below $500,000—became the basis for widespread reforms to sexual harassment policies and personnel practices. Besides, agencies routinely issue subpoenas in cases worth less than $500,000, and private discovery may otherwise be much less burdensome than a thorough investigation by, say, the SEC or the EEOC.

Before proceeding, a word about the Article’s limitations is in order. Although the Article explores the regulatory theory of discovery, it does not argue that the current amount or breadth of discovery is systemically optimal. There may be areas where waste needs cutting back and others where broader discovery is needed. Nor does the Article argue that ex post regulation via litigation is preferable to ex ante regulation via the administrative state. It necessarily sets this question—along with associated empirical questions—to the side. Relatedly, the Article relies on important examples like the Disney, Argentina, and Faragher cases, where discovery was beneficial, but does not claim that regulatory discovery is always beneficial. Indeed, in the analogous agency context, critics of the administrative state have long complained about protracted and wasteful agency investigations that serve only to justify the initial decision to initiate an investigation. The Article’s claim is only that discovery serves regulatory purposes comparable to administrative subpoena power, for better or worse.

As a final limitation, the Article makes a claim about regulatory discovery in the context of private-enforcement statutes that may be distinct from common law or tort claims. While discovery surely can serve as regulation in mass torts, the analytic framework and its underlying legitimacy are somewhat different. Private enforcement derives legitimacy from Congress’s deliberate choice to empower private plaintiffs either to complement or replace administrative agencies.28Farhang, supra note 13, at 64 (“[L]egislators deploy private litigants and plaintiffs’ attorneys as a source of state capacity . . . contemplat[ing] a high degree of intentionality.”). This choice is why private discovery in those claims is analogous to administrative subpoenas. Tort claims, by contrast, rely on a long common law tradition based mostly on state law. Discovery in that context must therefore be grounded in a different theory that may or may not support an analogy to agency subpoena power. Nonetheless, discovery in mass torts cases produces similar effects, so it may be illustrative of regulatory discovery. For that and other reasons, the Article uses examples from the tort context but leaves the necessary theory building to future research.

The discussion that follows proceeds in four Parts. Part I frames the problem of discovery costs and the Supreme Court’s turn to doctrine to solve it. This Part situates the project within existing discovery scholarship and sketches the framework around which discovery theory must operate. That theory is then developed in Part II, with the three traditional theories of fairness, equality, and trial narrowing. Part III—the heart of the article—introduces an approach to discovery based on regulation. Finally, Part IV pulls these threads together to provide a novel way to address discovery disputes.

I. Identifying the Problem: Discovery-Costs Disputes

For better or worse, discovery is the central and often outcome-determinative procedure in American litigation.29Nora Freeman Engstrom, The Lessons of Lone Pine, 129 Yale L.J. 2, 67 (2019) (“By the late 1980s . . . [i]t was discovery, not trial—the deposition, not the cross-examination—that became the focal point of American civil litigation.”); Arthur R. Miller, The Pretrial Rush to Judgment: Are the “Litigation Explosion,” “Liability Crisis,” and Efficiency Clichés Eroding Our Day in Court and Jury Trial Commitments?, 78 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 982, 1076 (2003); Stephen C. Yeazell, Essay, The Misunderstood Consequences of Modern Civil Process, 1994 Wis. L. Rev. 631, 637–39 (noting that discovery disputes are often dispositive to litigation outcomes). For purposes of this paper, I am referring almost entirely to pretrial discovery. I set aside the quite different world of post-judgment discovery. See generally Aaron D. Simowitz, Transnational Enforcement Discovery, 83 Fordham L. Rev. 3293 (2015). It has a long history rooted in equity, where flexibility was paramount.30Amalia D. Kessler, Our Inquisitorial Tradition: Equity Procedure, Due Process, and the Search for an Alternative to the Adversarial, 90 Cornell L. Rev. 1181 (2005). Away from the danger of common law juries, equity judges developed procedures that allowed parties to engage in a protracted process of producing information from and to each other. Whether through depositions or broad document requests that extended even to third parties, equity saw discovery as the definitive device for setting the tables of a judicial decision. By contrast, the common law world emphasized pleadings and trials as the information flushing events to decide a case.

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure’s drafters combined common law and equity discovery procedures into one whole, and the system later evolved into the modern Rules 26–37, which allow parties to obtain broad information on the central facts of a case before trial. One defining feature of the current system—amended several times post-1938—is that discovery is “extremely broad,”31United States v. Leggett & Platt, Inc., 542 F.2d 655, 657 (6th Cir. 1976) (citations omitted). allowing parties to obtain information “regarding any matter, not privileged, that is relevant to the subject matter involved in the action, whether or not the information sought will be admissible at trial.”32Jack H. Friedenthal, Mary Kay Kane & Arthur R. Miller, Civil Procedure § 7.2 (2d ed. 1993) (citing the pre-2015 discovery language that has been amended). The main drafter of the discovery rules, Edson Sunderland, argued that “[t]he new federal rules . . . authoriz[e] the parties themselves to employ an almost unlimited discovery.”33Edson R. Sunderland, Discovery Before Trial Under the New Federal Rules, 15 Tenn. L. Rev. 737, 738 (1939). The rules seek a comprehensive exchange of information led by the parties. That is why the rules authorize initial disclosures (a recent development adopted in the 1990s), subpoenas, depositions, interrogatories, physical examinations, property inspections, requests for admissions, and even an iterative process where parties can engage in new information requests based on old requests. All of this leads to a far-reaching release of information related to the case and claims.

It is difficult to overstate the uniquely American nature of this information disclosure system. Discovery has become an integral part of the American concept of due process—so much so that some argue discovery is of constitutional foundation.34Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr., From Whom No Secrets Are Hid, 76 Tex. L. Rev. 1665, 1694 (1998); Subrin, supra note 2. Other countries, however, consider it anathema. In common law countries, discovery can sometimes include broad document productions and mandatory disclosures, but it is typically limited by “specific pleading, the short time limit imposed for document production, and the definition of the obligation to produce.”35Hazard, supra note 34, at 1681. The combination of these factors results in a “considerably narrower” exchange of information vis-à-vis the United States.36Id. In civil law countries, there is no broad exchange of documents or disclosures, and the process is wholly supervised by a judge who makes it her goal to keep the case constrained and focused.37Id. at 1682. These inquisitorial systems give parties very little power to engage in wide-ranging information requests, and they prohibit depositions.38See Kessler, supra note 30, at 1261 (discussing French civil procedure, among others). Differences between our broad discovery system and the narrow approach prevalent in every other country have thus provoked significant foreign critiques.39Diego Zambrano, A Comity of Errors: The Rise, Fall, and Return of International Comity in Transnational Discovery, 44 Berkeley J. Int’l L. 157, 170–71 (2016).

Setting foreign comparisons aside, to speak of broad discovery as a homogeneous coherent procedure is misleading because there is no single process that is invariant from case to case. There are large complex litigation cases—a diverse set in itself that often involves mass torts and statutory-enforcement cases—where discovery can take up years and produce millions of records and dozens of depositions. But these are a small minority of all cases in the federal docket. In the run-of-the-mill case, litigants “employ[] no discovery at all, and a ‘substantial percentage’ of the [federal] docket employ[s] very little.”40Arthur R. Miller, From Conley to Twombly to Iqbal: A Double Play on the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 60 Duke L.J. 1, 62 (2010). Cases often settle immediately or in the early stages of discovery. Other cases need no discovery, and summary judgment is sufficient with only a few documents at hand. Yet other cases need only documentary discovery and no depositions at all. To understand discovery, we have to understand its inherent pluralism and case-dependent nature. Below, I address (a) scholarly and judicial debates about discovery costs, (b) the judicial development of doctrines meant to control discovery, and (c) that development’s problematic consequences.

A. The Discovery Costs Debates

Despite this pluralism, complex cases with extensive discovery have long shaped struggles over the role of discovery in public-law litigation and its attendant costs. Indeed, despite discovery’s rich heritage, debates for the past four decades have been bogged down almost entirely on the question of costs.41Brooke D. Coleman, One Percent Procedure, 91 Wash. L. Rev. 1005, 1060–61 (2016); Endo, Discovery Hydraulics, supra note 4, at 1343–44; Danya Shocair Reda, The Cost-and-Delay Narrative in Civil Justice Reform: Its Fallacies and Functions, 90 Or. L. Rev. 1085, 1123–24 (2012). After the emergence of class actions and the public-law bar in the late 1960s, litigation became embroiled in a battle between corporate defendants and newly empowered plaintiffs’ attorneys. In these litigation wars, corporate defendants launched attacks against any procedures that empowered plaintiffs’ attorneys, including not just class actions but also private rights of actions.42See Burbank & Farhang, supra note 3, at 15–16, 26, 141–43. Discovery, too, became entangled in this struggle over the role of litigation in the enforcement of public-law statutes.

Recently, scholarly articles about discovery have mostly focused on the problem of costs.43Jay Tidmarsh, Opting Out of Discovery, 71 Vand. L. Rev. 1801, 1813 (2018) (“[M]uch of the energy in U.S. procedural reform for the past thirty-five years has been directed toward solving the cost problem in discovery.”). As Seth Endo has summarized, an avalanche of discovery reform proposals all focus on solving the alleged cost problem, including: limits to the amount of discovery in all cases, a proportionality requirement, linking requests to the amount in controversy, mandatory stays pending a motion to dismiss, information sampling, dividing the process into phases, empowering judges (and availability of sanctions), ADR, expanding the use of bespoke discovery contracts, predictive coding and other machine learning, cost-shifting, quantum meruit cost recovery, and others.44Endo, supra note 4, at 1343–68; see also Jessica Erickson, Bespoke Discovery, 71 Vand. L. Rev. 1873, 1876 (2018); Engstrom & Gelbach, supra note 5, at 38–41.

All of these scholarly proposals draw from a four-decade-long debate about the appropriate scope of discovery. Beginning with the 1976 Pound Conference on civil procedure, “proposals for amendment to the rules have generally involved retreats from the broadest concept of discovery.”45Marcus, supra note 4, at 747. The Pound Conference prompted the creation of a variety of working groups and conferences with the sole goal of controlling discovery costs.46Id. at 752–53. The Carter Administration followed these efforts with a directive to a new antitrust commission, asking for a “revision of discovery practices in order to limit expensive and time-consuming inquiry into areas not germane to contested issues.”47Id. at 753 (quoting Exec. Order No. 12,022, 42 Fed. Reg. 61,441 § 2(1)(iii) (Dec. 5, 1977)). These efforts, and others, built substantial momentum for discovery reform that spread like a contagion and led to recurrent amendments to the rules.48See generally Burbank & Farhang, supra note 3; Stephen B. Burbank & Sean Farhang, Rulemaking and the Counterrevolution Against Federal Litigation: Discovery, in Pound Civ. Just. Inst., Who Will Write Your Rules: Your States Court or the Federal Judiciary? 24th Annual Forum for State Appellate Court Judges (2017), http://www.poundinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2016-forum-report-1.9.18.pdf [https://perma.cc/XV24-7YM3].

Since the turn of the century, discovery costs debates have been reshaped by the emergence of electronically stored information.49See Endo, supra note 4, 1319–20. Modern technologies have expanded the generation of information within corporations and regulated entities. This expansion has transformed discovery into a much more complicated process where “traditional practices” have been unable to “keep up with the explosion of the universe of discoverable material.”50Id. at 1320. Advisory Committee debates have responded to ESI with renewed proposals to address the problem of discovery costs. All told, the Committee has changed the discovery rules over a dozen times between 1980 and 2015.51Id. at 1327–28; Stephen B. Burbank, Sean Farhang & Herbert M. Kritzer, Private Enforcement, 17 Lewis & Clark L. Rev. 637, 657 & n.79 (2013).

Whether discovery costs are an actual problem—or just a proxy fight over the role of litigation in society—depends on how one slices up the federal docket.52As Danya Reda has discussed, concerns about discovery costs have never really matched actual empirical data showing that the system is not overly costly. Reda, supra note 41, at 1122–23. Here, I draw on Reda’s ideas in the specific context of discovery. Of course, abusive discovery exists, and discovery does impose significant costs in some cases.53See Joshua M. Koppel, Comment, Tailoring Discovery: Using Nontranssubstantive Rules to Reduce Waste and Abuse, 161 U. Pa. L. Rev. 243, 254 (2012). But the extent of “[t]he costs may be somewhat overstated—or partially self-inflicted—and certainly they are not universally imposed across the litigation universe.”54Id. at 252 n.52 (quoting Miller, supra note 40, at 62). Most empirical discovery studies consist of attorney or judicial surveys and very few peer into actual case data.55See, e.g., Fleming James, Jr., Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr. & John Leubsdorf, Civil Procedure § 5.2, at 288 n.7 (5th ed. 2001); Emery G. Lee III & Thomas E. Willging, Fed. Jud. Ctr., Preliminary Report to the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Civil Rules (2009); Thomas E. Willging, John Shapard, Donna Stienstra & Dean Miletich, Fed. Jud. Ctr., Discovery and Disclosure Practice, Problems, and Proposals for Change: A Case-Based National Survey of Counsel in Closed Federal Civil Cases 1–2, 4, 8, 14–16 tbls.3, 4 & 5 (1997); Judith A. McKenna & Elizabeth C. Wiggins, Empirical Research on Civil Discovery, 39 B.C. L. Rev. 785, 790–92 (1998); Mullenix, supra note 3, at 684–85; Reda, supra note 41, at 1123–24. But a review of existing studies of federal litigation produces a few common conclusions:

- Most civil cases (>50%) involve no discovery or very limited discovery;56See, e.g., Paul Connolly, Edith A. Holleman & Michael J. Kuhlman, Fed. Jud. Ctr., Judicial Controls and the Civil Litigation Process: Discovery 28 (1978); Joseph L. Ebersole & Barlow Burke, Fed. Jud. Ctr., Discovery Problems in Civil Cases 5 (1980); James S. Kakalik, Deborah R. Hensler, Daniel McCaffrey, Marian Oshiro, Nicholas M. Page & Mary E. Vaiana, RAND Inst. for Civ. Just., Discovery Management: Further Analysis of the Civil Justice Reform Act Evaluation Data, at xx (1998); David M. Trubek, Austin Sarat, William L.F. Felstiner, Herbert M. Kritze & Joel B. Grossman, The Costs of Ordinary Litigation, 31 UCLA L. Rev. 72, 89–90 (1983).

- Cases with discovery typically implicate costs that are proportional to the total stakes (median of discovery costs is 3.3% of the amount in controversy for defendants);57Lee & Willging, supra note 55, at 2; Emery G. Lee III & Thomas E. Willging, Defining the Problem of Cost in Federal Civil Litigation, 60 Duke L.J. 765, 770 (2010); Reda, supra note 41, at 1089.

- The median litigation costs (including discovery and attorneys’ fees) for defendants is $20,000;58Lee & Willging, supra note 55, at 2.

- High discovery costs are rare (less than 5% of cases);59McKenna & Wiggins, supra note 55, at 791.

- In cases with “high” discovery costs, expenditures may account for 32% or more of the amount in controversy;60Thomas E. Willging, Donna Stienstra, John Shapard & Dean Miletich, An Empirical Study of Discovery and Disclosure Practice Under the 1993 Federal Rule Amendments, 39 B.C. L. Rev. 525, 531 (1998).

- Cases with voluminous discovery often involve complex litigation;61See Ebersole & Burke, supra note 56. This Federal Judicial Center study doesn’t define complex litigation itself, but it refers to the Manual for Complex Litigation (Fourth) (2004), which notes that “the term ‘complex litigation’ [is not] susceptible to any bright-line definition,” although it clearly includes both private enforcement and mass tort litigation. Id. at 1, 3.

- Lawyers perceive that e-discovery has increased costs;62Am. Coll. of Trial Laws., Final Report on the Joint Project of the American College of Trial Lawyers Task Force on Discovery and the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System 16 (2009).

- Despite little empirical support, many judges63Brookings Inst., Justice for All: Reducing Costs and Delay in Civil Litigation 7 (1989); C. Ronald Ellington, A Study of Sanctions for Discovery Abuse (1979). and lawyers64Laws. for Civ. Just. et al., Litigation Cost Survey of Major Companies 15–16 (2010); Litig. Section, Am. Bar Ass’n, Member Survey on Civil Practice: Detailed Report 2 (2009); Louis Harris & Assocs., Inc., Project No. 881023, Procedural Reform of the Civil Justice System 20 (1989). perceive discovery abuse as a significant problem.

The available evidence seems to show that “the federal civil system is highly effective in most cases, that total costs develop in line with stakes, and that discovery volume and cost is proportional to the amount at stake.”65Reda, supra note 41, at 1089. Costs remain an issue in a minority of complex litigation cases that account for the discovery costs contagion.

B. Discovery Avoidance

For decades, the Supreme Court and lower courts have actively participated in and shaped discovery-costs debates. In many cases, courts have used discovery as a cudgel to shape nearly every facet of the modern civil-litigation system, including in some of the most important procedural and substantive cases. Courts have developed two tracks in their attempts to fight discovery. At first, courts and the Advisory Committee focused on the idea of judicial management of the discovery process.66Miller, supra note 40, at 54; Terence Dunworth & James S. Kakalik, Preliminary Observations on Implementation of the Pilot Program of the Civil Justice Reform Act of 1990, 46 Stan. L. Rev. 1303 (1994). But more recently, courts have engaged in a systematic attempt to control discovery costs by raising prediscovery barriers, including pleading standards, qualified immunity, and arbitration. I term these efforts “discovery avoidance.” This has led to the proliferation of doctrines parasitic to discovery across the litigation landscape.

Take, for example, the recently restated foundations of qualified immunity doctrine. The Court has repeatedly imputed to qualified immunity a prophylactic role against the burden of discovery costs on police officers. As recently detailed by Joanna Schwartz, the Court has “focused increasingly on . . . the need to protect government officials from nonfinancial burdens associated with discovery and trial. This desire has arguably shaped qualified immunity more than any other policy justification for the doctrine.”67Joanna C. Schwartz, How Qualified Immunity Fails, 127 Yale L.J. 2, 9 (2017); see also Joanna C. Schwartz, Civil Rights Ecosystems, 118 Mich. L. Rev. (2020) (discussing qualified immunity among the legal rules and remedies that define “civil rights ecosystems”—collections of interconnected and interactive legal actors). The doctrine has progressively incorporated discovery costs as a larger concern. In the seminal case Harlow v. Fitzgerald, the Court justified qualified immunity as a bulwark against “the expenses of litigation, the diversion of official energy from pressing public issues, and the deterrence of able citizens from acceptance of public office,” as well as the possibility that lawsuits would affect officials’ discharge of their duties.68Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800, 814 (1982). As a second-order concern, the Court also warned of the danger of “broad-ranging discovery and the deposing of numerous persons, including an official’s professional colleagues.”69Id. at 817. Only three years later, the Court emphasized the danger of discovery to “be avoided if possible”70Mitchell v. Forsyth, 472 U.S. 511, 526 (1985). but still focused on its other justifications. By contrast, in the recent Ashcroft v. Iqbal, the Court claimed that “[t]he basic thrust of the qualified-immunity doctrine is to free officials from the concerns of litigation, including ‘avoidance of disruptive discovery.’”71Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 685 (2009) (quoting Siegert v. Gilley, 500 U.S. 226, 236 (1991) (Kennedy, J., concurring in judgment)). This evolution shows discovery’s newfound role in qualified immunity.

Another example of this kind of marriage between discovery and other procedures is found in the securities litigation context. Specifically, one of the bluntest and most significant discovery-filtering mechanisms is the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA).72See Gorga & Halberstam, supra note 13, at 1392–93; Hillary A. Sale, Heightened Pleading and Discovery Stays: An Analysis of the Effect of the PSLRA’s Internal-Information Standard on ’33 and ’34 Act Claims, 76 Wash. U. L.Q. 537, 552–53 (1998). That statute contains a package of reforms intended to diminish the power of plaintiffs’ attorneys in securities litigation, especially by weakening pretrial discovery. The House Report is littered with references to the danger of discovery costs: “[T]he abuse of the discovery process to impose costs [is] so burdensome that it is often economical for the victimized party to settle”; “The cost of discovery often forces innocent parties to settle frivolous securities class actions,”; “The House and Senate heard testimony that discovery in securities class actions often resembles a fishing expedition.”73H.R. Rep. No. 104-369, at 31, 37 (1995) (Conf. Rep.); see also Gorga & Halberstam, supra note 13, at 1392 (“The costs and abuses of discovery were . . . a key focus of the debates concerning the . . . (PSLRA).”). Accordingly, the statute raises pleading standards for securities claims and obligates courts to issue a discovery stay while a motion to dismiss is pending. The Supreme Court noted about these congressional changes to pleading that “[t]he basic purpose of the heightened pleading requirement . . . is to protect defendants from the costs of discovery and trial in unmeritorious cases.”74Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd., 551 U.S. 308, 335–36 (2007) (Stevens, J., dissenting). Again, through both of these means, discovery is completely avoided.

Qualified immunity and the PSLRA are only two of a constellation of similar changes intended to blunt discovery, including in the contexts of pleading, class actions, Lone Pine orders, and arbitration. A very similar kind of logic has been at work in the Supreme Court’s pleading jurisprudence. As is by now widely known, the Supreme Court heightened pleading standards in Twombly and Iqbal, largely because of a concern over discovery costs. The Court embraced the implicit theory that pleading should serve as a filter that reserves discovery for cases that can meet an initial threshold.75See, e.g., Jonah B. Gelbach, Locking the Doors to Discovery? Assessing the Effects of Twombly and Iqbal on Access to Discovery, 121 Yale L.J. 2270, 2285 (2012); J. Scott Pritchard, Comment, The Hidden Costs of Pleading Plausibility: Examining the Impact of Twombly and Iqbal on Employment Discrimination Complaints and the EEOC’s Litigation and Mediation Efforts, 83 Temp. L. Rev. 757, 780, 780 n.211 (2011); Suja A. Thomas, The New Summary Judgment Motion: The Motion to Dismiss under Iqbal and Twombly, 14 Lewis & Clark L. Rev. 15, 25 (2010). In the class-actions world, federal courts developed the idea of a “rigorous review” of certification motions in the 1990s partly because certification was perceived as opening the door to crippling discovery costs. Along the same lines, courts began to enforce the Federal Arbitration Act aggressively, allowing defendants to opt out of the litigation system entirely.76J. Maria Glover, Disappearing Claims and the Erosion of Substantive Law, 124 Yale L.J. 3052, 3054 (2015). In an arbitration world divorced from the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, discovery avoidance became paramount. In yet another context, courts faced with mass tort claims have developed “Lone Pine” orders, requiring plaintiffs to supply evidence of injury, exposure, and causation under penalty of dismissal—sometimes before discovery. This can be seen as yet another example of discovery avoidance.77See Engstrom, supra note 29. In these cases, policing class claims before they are certified, requiring more evidence early on, and forcing plaintiffs into arbitration became ways to avoid discovery.

Setting these examples aside, we may worry that discovery concerns are merely window dressing in these cases—in what is more likely a struggle over the role of litigation in society. Although that is likely true for many judges, there are also reasons to believe judicial concerns about discovery are real. Decades of survey work have found that a significant percentage of federal judges voice strong concerns about discovery as “unnecessary,” “expensive,” and overly “burdensome.”78See Ellington, supra note 63; supra notes 54–64. This apparent judicial attitude correlates with over a dozen initiatives to address discovery costs: from Justice Burger’s Pound Conference on litigation costs in 1976, to the 1990s disclosure amendments, all the way to the 2015 proportionality amendments to the rules. Moreover, this judicial perception of discovery does not seem to be an entirely partisan phenomenon. Twombly’s attack on discovery costs was authored by the centrist Justice Souter in a 7–2 decision (although Iqbal was 5–4); discovery reforms have mostly been the product of judicial consensus; and the judiciary has otherwise attempted to control discovery through amendments to the rules.79Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662 (2009); Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544 (2007). This indicates that perhaps concerns in this context are genuine. But even if some of the concerns about discovery are sincere, the way judges have operationalized those concerns has created downstream harms that may be disproportionate to the problem.

C. The Problem with an Obsession over Costs

The combined developments of rule amendments and discovery avoidance and management, as well as the nearly complete domination of scholarly debates by costs, have imposed procedural hurdles that stand in the way of a plaintiff’s day in court and have disfigured case law and rulemaking.80Scott Dodson, New Pleading, New Discovery, 109 Mich. L. Rev. 53, 64 (2010) (“The reason why the Supreme Court has pushed this change seems fairly obvious: the Court is concerned with high discovery costs.”). There are a flurry of problems with the changes spurred by the discovery-costs rhetoric, including the following three:

First, creating or reinforcing doctrines tethered to discovery runs the destabilizing risk of tying slow-moving legal principles to a quickly moving target. Legal devices like pleading standards, qualified immunity, and the PSLRA are now fixed deeply into the U.S. Code or court precedents. But discovery, by contrast, can change quickly due to technological developments or Advisory Committee changes. Thus, affixing these doctrines to the vagaries of the discovery process is potentially destabilizing. Because discovery now sits at the center of a network of doctrines, any changes to its reach should (but may not) provoke concomitant changes throughout the litigation system. For example, if technological changes like machine learning reduce discovery costs, discovery-dependent doctrines like pleading standards should immediately adjust, rendering existing case law outdated. Even more, the Advisory Committee proposes rule changes on a regular basis. An amendment to Federal Rule 26 that successfully reduces costs should have a cascading effect on every doctrine that was justified as a prophylactic against costly discovery: Twombly and Iqbal would be redundant; rules that encourage settlement unnecessary; qualified immunity obsolete; and even “rigorous” policing of class actions outdated. The difficulty, of course, is that discovery-avoidance doctrines will not adapt and therefore the system will be miscalibrated based on an outdated picture of discovery.

The expansion of these discovery-avoidance decisions or statutes creates the danger of doctrinal accretion. Doctrines can pile up on top of other doctrines. For instance, a current class action against the police runs the danger of running into three separate discovery-dependent doctrines: plausibility pleading, qualified immunity, and rigorous review of class certification. A plaintiff in this case is thus faced with three independent, but now accreted, doctrines that are supposed to fight off the same thing—discovery costs. This overdeters claims, is inefficient, and overcomplicates litigation.

Second, discovery avoidance empowers judges to create new doctrines out of thin air and sidelines the expertise and flexibility of the Advisory Committee. When discovery control rests on the wording of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the Advisory Committee can carefully consider reforms and recalibrate the system to fit new technologies or legal developments. But the Supreme Court’s turn to doctrine to control discovery weakens that equilibrium and empowers ideological judges. As previous scholarship has explored, the Reagan and Bush Administrations began appointing judges committed to litigation reform in the 1980s.81See, e.g., Carl Tobias, Rethinking Federal Judicial Selection, 1993 BYU L. Rev. 1257, 1264–74; cf. Stephen B. Burbank & Sean Farhang, Litigation Reform: An Institutional Approach, 162 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1543, 1551–55 (2014) (discussing litigation reform during the Reagan Administration more generally). Many of these judges shared the view that plaintiffs’ attorneys had too much leeway under our procedural paradigm.82See, e.g., Burbank & Farhang, supra note 81, at 1552–55 (discussing the Reagan Administration’s efforts to curtail “contingency litigation”) They therefore embraced the idea of a judicial retrenchment of civil procedure as a remedy. Debates over discovery costs have given these judges—rather than the Advisory Committee—a tool to effect procedural change. Changes to qualified immunity or the PSLRA are all etched on the case law. That move disempowers the Committee and also constitutes a shift away from Advisory Committee review of empirical studies of discovery. That development contributes, yet again, to the miscalibration of the discovery process.83Crawford-El v. Britton, 523 U.S. 574, 595 (1998) (characterizing the “Court of Appeals’ indirect effort to regulate discovery” as the use of “a blunt instrument that carries a high cost”).

Finally, a sustained overemphasis on discovery costs has weakened the discovery process more generally and robs the system of necessary improvements. While the Court initially recognized that discovery rules “are to be accorded a broad and liberal treatment,” it has now moved toward a much more constrained process.84Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U.S. 495, 507 (1947). And this goes beyond its embrace of discovery avoidance. Beginning with a Justice Powell concurrence that raised the specter of “undue and uncontrolled discovery,”85Herbert v. Lando, 441 U.S. 153, 179 (1979) (Powell, J., concurring). the Supreme Court has complained about broad discovery more generally, culminating with the Chief Justice’s embrace of the 2015 reforms to discovery that were intended to constrain the process.86See Fed. R. Civ. P. 26 (amended Dec. 1, 2015). This subtle shift from avoidance toward rejection is likely to weaken the entire discovery process.

* * *

All of this means that discovery has helped install a series of procedural doctrines that stand in the way of a plaintiff’s day in court and on the way has disfigured case law and the rulemaking process.87See Dodson, supra note 80, at 64.

II. Traditional Theories of Discovery

Stepping back from the marriage of discovery and costs, the core difficulty is how to move the debate forward—how to actually determine whether we have an optimal discovery system. This question cannot solely be answered by discussions about costs but must also be based on theory.88See generally Robert G. Bone, Making Effective Rules: The Need for Procedure Theory, 61 Okla. L. Rev. 319 (2008). For when it comes to assessing discovery, we should understand that it is a plural device that serves many purposes at once that, at first sight, are difficult to see. Only theory can allow us to properly weigh discovery costs against other values in litigation and can ground the basic question: Why do we have a discovery system and what are we attempting to achieve? In this Part, I focus on this question but use the word “theory” loosely to refer to background justifications or rationales. Many of the “theories” discussed below could rightly be described as values that are nested within broader political theories.

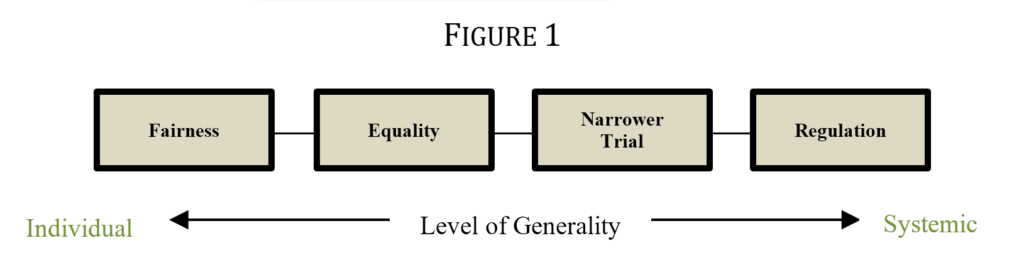

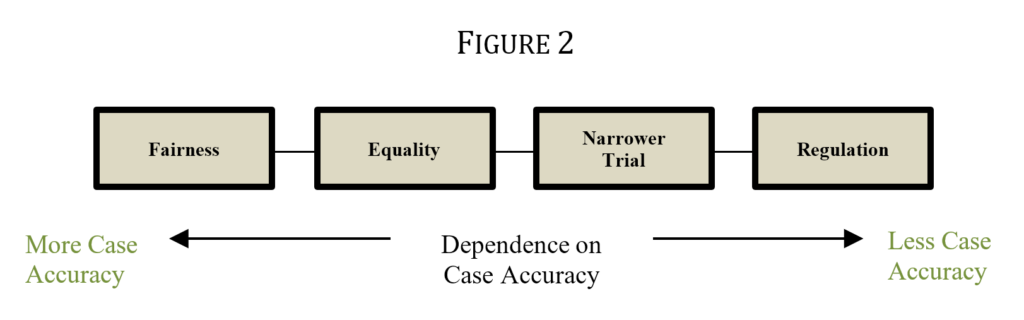

As noted earlier, existing discovery jurisprudence does not provide a full theoretical account because it relies on an incomplete view that discovery exists to promote fairness, accuracy, and settlements. That traditional view argues that discovery is beneficial because a full exchange of information results in a fair and just resolution of a dispute89See Brazil, supra note 6, at 1298; E. Donald Elliott, How We Got Here: A Brief History of Requester-Pays and Other Incentive Systems to Supplement Judicial Management of Discovery, 71 Vand. L. Rev. 1785, 1788 (2018); Irving R. Kaufman, Judicial Control Over Discovery, 28 F.R.D. 111, 125 (1962) (“The federal rules are designed to find the truth . . . .”); Alexandra D. Lahav, A Proposal to End Discovery Abuse, 71 Vand. L. Rev. 2037, 2045 (2018); Tidmarsh, supra note 42, at 1811 (“Principally, [discovery] ensures a rational and accurate process for adjudicating or settling claims.”). This justification was clearly on the mind of the Federal Rules’ framers. See Alexander Holtzoff, Instruments of Discovery Under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 41 Mich. L. Rev. 205, 205 (1942); Subrin, supra note 8, at 745. The Supreme Court has also repeatedly endorsed the fairness rationale for discovery. See Cheney v. U.S. Dist. Court, 542 U.S. 367, 392 (2004) (Stevens, J., concurring); United States v. Procter & Gamble Co., 356 U.S. 677, 682 (1958); see also Greyhound Lines, Inc. v. Miller, 402 F.2d 134, 143 (8th Cir. 1968) (“The purpose of our modern discovery procedure is to narrow the issues, to eliminate surprise, and to achieve substantial justice.”). and a more accurate outcome,90See Procter & Gamble, 356 U.S. at 682; Greyhound Lines, Inc., 402 F.2d at 143; Brazil, supra note 6, at 1302. and it allows one-shot plaintiffs to obtain critical information from repeat player defendants.91See Burke v. N.Y.C. Police Dept., 115 F.R.D. 220, 225 (S.D.N.Y. 1987) (“[T]he overriding policy [of discovery] is one of disclosure of relevant information in the interest of promoting the search for truth . . . .”); Lahav, supra note 89, at 2039, 2042–45 (discussing discovery’s purposes in light of information asymmetries between plaintiffs and defendants). Moreover, by forcing the parties to reveal all their arguments and evidence, discovery renders trials redundant and nudges the parties toward settlement.92Cooter & Rubinfeld, supra note 8, at 436. Despite its prominence, however, the fairness-accuracy-settlement conventional wisdom suffers from significant limitations—discussed further infra in Part III—because it misses the role that discovery has grown to play in complex litigation and private-enforcement cases.93Although scholars have admirably explored some justifications. See Robert G. Bone, Agreeing to Fair Process: The Problem with Contractarian Theories of Procedural Fairness, 83 B.U. L. Rev. 485, 488–89 (2003); Cooter & Rubinfeld, supra note 8, at 436; Louis Kaplow & Steven Shavell, Fairness Versus Welfare: Notes on the Pareto Principle, Preferences, and Distributive Justice, 32 J. Legal Stud. 331 (2003); Jon O. Newman, Rethinking Fairness: Perspectives on the Litigation Process, 94 Yale L.J. 1643, 1646–47 (1985). This Article draws on this literature but attempts to fully develop the regulatory theory, see infra Part III, and brings all theories together in a comprehensive analysis. My goal in this Section is to very briefly explain the conventional view of discovery, which is based on the promotion of (1) fairness, (2) equality, and (3) trial narrowing or settlements. This exploration lays the groundwork for the full development of regulatory discovery in Part III.

Fairness. The most obvious justification for liberal discovery is that a full exchange of information results in a fair resolution of a dispute and promotes the ends of justice.94Brazil, supra note 6, at 1296. As Justice Stevens noted, “[b]road discovery should be encouraged when it serves the salutary purpose of facilitating the prompt and fair resolution of concrete disputes.”95Cheney v. U.S. District Court, 542 U.S. 367, 392 (2004) (Stevens, J., concurring). Fairness could be understood to promote goals that are consonant with procedural justice, including participation, accuracy, and efficiency. 96Solum, supra note 7, at 237, 244–60; Martin H. Redish, Electronic Discovery and the Litigation Matrix, 51 Duke L.J. 561, 567 (2001). A fair process is one that “guarantees rights of meaningful participation,” and “notice and opportunity to be heard.”97Solum, supra note 7, at 237, 244–60. With an accuracy-participation-efficiency mantra as the North Star of the system, it follows that discovery should be broad rather than narrow.98See Brazil, supra note 6. Ex ante, the more information that can be produced, the more the factfinder can achieve an accurate outcome. In theory, limits to discovery might be antithetical to fairness. Although this fairness theory has been fundamental to doctrinal developments in discovery, it has always failed to account for the entirety of the discovery process.

Equality. Broad discovery has the potential to serve as an equalizer of litigant resources. This justification is closely related to the fairness one and is sometimes treated as the same in the literature. But unlike the fairness account, this justification for discovery begins with the observation that the litigation system is riddled with resource asymmetries.99For the traditional treatment of resource asymmetries from the law and society scholarship, see Marc Galanter, Why the “Haves” Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change, 9 Law & Soc’y Rev. 95 (1974). For the traditional law and economics approaches, see George L. Priest & Benjamin Klein, The Selection of Disputes for Litigation, 13 J. Legal Stud. 1, 20 (1984), hypothesizing that there will be a “tendency toward 50 percent plaintiff victories” among litigated cases, and Steven Shavell, Suit, Settlement, and Trial: A Theoretical Analysis Under Alternative Methods for the Allocation of Legal Costs, 11 J. Legal Stud. 55, 56 (1982), describing the cost-benefit analyses parties engage at each stage of litigation. The role of discovery and procedure is to ameliorate those asymmetries, create a level playing field, eliminate trial “surprises,” and give different litigants equal access to justice.100Solum, supra note 7, at 287–88; see also Charles E. Clark, Edson Sunderland and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 58 Mich. L. Rev. 6, 11 (1959) (arguing that discovery under the 1938 Rules “d[id] away with ‘surprise’ as a tactical advantage in litigation as a game”); Dodson, supra note 80, at 73–86 (proposing a new form of discovery to deal with information asymmetries in the wake of heightened pleading). It is, in other words, to promote equality.101See Martin H. Redish & Lawrence C. Marshall, Adjudicatory Independence and the Values of Procedural Due Process, 95 Yale L.J. 455, 484 (1986) (“One value that might conceivably be fostered by procedural due process is the goal of equality.”); William B. Rubenstein, The Concept of Equality in Civil Procedure, 23 Cardozo L. Rev. 1865, 1879 (2002) (“Modern procedural practices themselves can also have equality-enhancing consequences. This is most obvious in the Federal Rules’ embrace of notice pleading and liberal discovery.”). That concept is of course “notoriously slippery . . . , and its procedural implications are puzzling.”102Jerry L. Mashaw, Administrative Due Process: The Quest for a Dignitary Theory, 61 B.U. L. Rev. 885, 899 (1981). But in the context of discovery, we should be concerned with the concept that William Rubenstein calls “equipage equality.”103Rubenstein, supra note 101, at 1867. That is the idea that adversarialism requires “a real battle between equally-armed contestants . . . [with] some measure of equality in the litigants’ capacities to produce their proofs and arguments.”104Id. at 1867–68. See also Frank I. Michelman, The Supreme Court and Litigation Access Fees: The Right to Protect One’s Rights (pt. 1), 1973 Duke L.J. 1153. See generally Judith Resnik, Money Matters: Judicial Market Interventions Creating Subsidies and Awarding Fees and Costs in Individual and Aggregate Litigation, 148 U. Pa. L. Rev. 2119, 2136 (2000) (“Equipage for civil litigants—from filing fees to investigation to counsel to experts—is generally left either to the legislature or to the market.”). This kind of equality is not concerned with substantive outcomes or even equality of treatment across cases.105Although equality may not promote justice or fair outcomes. See, e.g., Paul Stancil, Substantive Equality and Procedural Justice, 102 Iowa L. Rev. 1633 (2017). Rather, Rubenstein argues that its focus is on the procedural equipment that the system gives litigants—the arrows that litigants can have in their quiver. Discovery can arm litigants with tools to remedy the inherent asymmetry between plaintiffs and defendants.106Robert G. Bone, Modeling Frivolous Suits, 145 U. Pa. L. Rev. 519, 542 (1997); See also Rubenstein, supra note 101, at 1880 (“Broad discovery has the effect of equalizing the information available to each side in the lawsuit.”). It is a powerful factfinding measure that provides small litigants access to documents or witness information that are otherwise only in the hands of a corporate defendant.107Of course, confidentiality provisions can defeat this. See Seth Katsuya Endo, Contracting for Confidential Discovery, 53 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1249 (2020). And “discovery can also work against poorer litigants [who] can be flooded with discovery requests.” Rubenstein, supra note 101, at 1880. Discovery thus attempts to remedy informational asymmetries.

Narrowing Trials and Promoting Settlement. An institutional and historical account of discovery sees it as a tool that can narrow the scope of trial, promote settlement, and perhaps sometimes replace common law trials and juries.108See Engstrom, supra note 29, at 2, 35, 67–68; Yeazell, supra note 8, at 950–54; cf. Langbein, supra note 1, at 533 (discussing how discovery substituted for the disclosure function of pleading in the Federal Rules). This rationale was frequently invoked by the framers of the Federal Rules. See James A. Pike & John W. Willis, Federal Discovery in Operation, 7 U. Chi. L. Rev. 297 (1940) (endorsing the 1938 Rules on the grounds that discovery procedures reduce burdens at trial); James A. Pike & John W. Willis, The New Federal Deposition-Discovery Procedure (pt. 1), 38 Colum. L. Rev. 1179 (1938) (same); Edson R. Sunderland, Discovery Before Trial Under the New Federal Rules, 15 Tenn. L. Rev. 737, 737–38 (1939) (describing a system that waits for trial to flush out information as “economically extravagant” and a “wasteful method of civil litigation” and distinguishing the Federal Rules); Sunderland, supra note 33, at 19–28. At common law, there was no robust discovery and trial was instead the defining information-flushing event of a case. In a system with jurors and no discovery, however, trials were expensive and burdensome and allowed for potential late-stage surprises. One way to remedy that problem was to expand the pretrial stage and allow the parties to fully explore relevant documents and witnesses, narrowing issues for trial or even avoiding it. Some of the Federal Rules drafters sought to avoid the burdens of the common law trial by infusing the system with equity’s flexibility and broad discovery.109Stephen N. Subrin, How Equity Conquered Common Law: The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in Historical Perspective, 135 U. Pa. L. Rev. 909, 956–61 (1987). In other words, they sought to make the pretrial stage the fundamental information-exchanging event. Borrowing heavily from equity and the common law trial, the federal rules allowed broad document requests and regularized the concept of oral depositions, allowing the parties to directly interview the main witnesses outside of judicial supervision.110Kessler, supra note 30 at 1230–31, 1253 (discussing how depositions mutated away from masters to party-led questioning); see also Robin J. Effron, Ousted: The New Dynamics of Privatized Procedure and Judicial Discretion, 98 B.U. L. Rev. 127, 141 (2018) (“[T]he FRCP not only tolerate private procedural ordering during discovery, but are designed to promote it.”). The main drafter of the discovery rules, Edson Sunderland, argued that broad discovery would make trials narrower or even sometimes unnecessary111Sunderland, supra note 8, at 75; see also Subrin, supra note 8, at 736. and may, along with other pretrial procedures, “bring parties to a point where they will seriously discuss settlement.”112Edson R. Sunderland, Scope and Method of Discovery Before Trial, 42 Yale L.J. 863, 864 (1933); Tidmarsh, supra note 43, at 1808 n.3 (discussing Edson Sunderland’s prosettlement views).

As expected, discovery has come to serve as one of the main prosettlement nudges in the procedure toolkit. While discovery and trials are separate stages of litigation, they are nonetheless closely related because discovery shapes the parties’ decision whether to settle or litigate.113See Yeazell, supra note 8, at 950–54. A legal case can generally be decided via dismissal, settlement, or a final judicial decision. If the claim is meritorious, settlement can be highly efficient because it saves the high transaction costs of trials. Under a standard economic view of litigation, parties decide to file suit (and settle or litigate) depending on their probability of success at trial, amount in dispute, and costs of litigation.114See John P. Gould, The Economics of Legal Conflicts, 2 J. Legal Stud. 279 (1973); William M. Landes, An Economic Analysis of the Courts, 14 J.L. & Econ. 61 (1971); Richard A. Posner, An Economic Approach to Legal Procedure and Judicial Administration, 2 J. Legal Stud. 399 (1973). By forcing the parties to engage in a thorough exchange of information, discovery shapes the parties’ calculation of probable success and therefore “increases settlements and decreases trials,”115Cooter & Rubinfeld, supra note 8, at 436. even if it also forces the parties to reveal weaknesses in their case. Discovery allows the parties to share the trial transaction costs as bargaining surplus.

Since at least 1938, thanks partly to broad discovery, the system has slowly evolved away from trials and toward an increasing number of dispositive motions or settlements. It is possible to justify this shift, and expensive discovery, because it avoids the greater costs of impaneling juries and conducting trials.116But see John Bronsteen, Against Summary Judgment, 75 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 522, 533 (2007). But displacing trials and juries brings its own tradeoffs. The drafters may have miscalculated by importing expensive inquisitorial discovery devices “into a common-law-based adversarial framework after 1938.”117Kessler, supra note 30, at 1184. Moreover, discovery may not always be a full or adequate substitute for trials, because it deprives judges and juries from the cases necessary to update the common law.118Burbank & Subrin, supra note 26, at 401. Despite these tradeoffs, the record shows that it was part and parcel of the project to create new procedural rules that discovery would often promote settlement and narrow trials.119Langbein, supra note 1, at 547.

* * *

These three theories (or more properly, rationales or justifications) have a wide variety of implications explored in Part IV. For now, it is sufficient to note that they are based on different principles—fairness, equality, and judicial economy (or narrowing trials)—and lead to distinct background values for discovery.

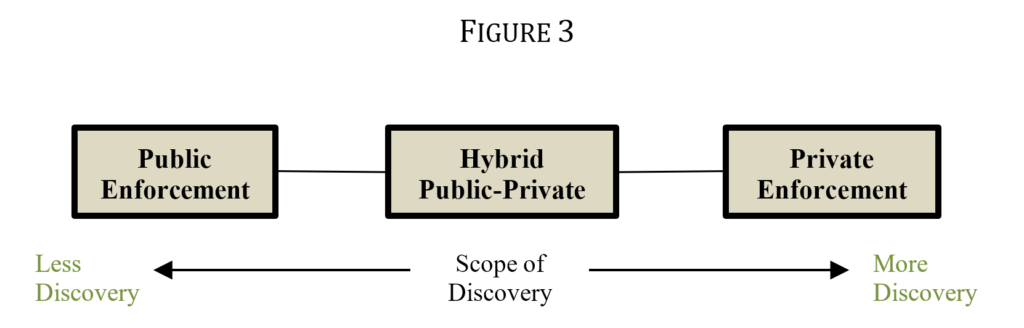

This Part explores in a systematic manner an additional way to conceptualize discovery. My main argument is that one of discovery’s core purposes in private-enforcement cases is actually divorced from adversarial litigation and is, instead, entirely about systemic regulation.120See, e.g., Burbank, supra note 9, at 649. To be clear, this kind of discovery is only relevant in cases that implicate public interests, not in private cases where individuals sue each other without any significant statutes or public norms at stake. In the private-enforcement context, Congress uniquely chose private claims, and attendant discovery, rather than agency regulation as the main administrative mechanism.121See infra notes 124–126. In those cases, litigation is a regulatory tool and broad discovery transforms into an essential regulatory device comparable to the administrative subpoena. By forcing parties to disclose large amounts of information, discovery deters harmful behavior and, most importantly, structures the primary behavior of regulated entities. As I discuss later, this means that courts should be more permissive with discovery requests in private-enforcement cases than in typical litigation.

Discovery even manifests in similar ways in the private action and administrative contexts. Both agency bureaucrats and private plaintiffs are engaged in the work of flushing out information using analogous tools in order to enforce some broad statutory mandate. Courts have thus treated private and public regulators in similar ways. In this section, I explain that discovery serves regulatory purposes in at least two ways: (1) it delegates to private plaintiffs government subpoena power to investigate wrongdoing; and (2) it has significant positive spillover effects on regulated entities and markets. Discovery therefore serves an important purpose in a system that relies on private litigants to enforce the law.122Several scholars have made some headway into the regulatory justification. Burbank & Farhang, supra note 3; Carrington, supra note 9, at 54; Jack H. Friedenthal, A Divided Supreme Court Adopts Discovery Amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 69 Calif. L. Rev. 806, 819–20 (1981); Higginbotham, supra note 9; see also Farhang, supra note 13, at 8; Burbank, supra note 9; Burbank et al., supra note 51, at 662–63; Matthew A. Shapiro, Delegating Procedure, 118 Colum. L. Rev. 983, 1007 (2018); Yeazell, supra note 8, at 950–54 (“The system, though essentially private and adversarial, can marshal facts in a manner that resembles an administrative investigation.”).

A. Discovery as the Lynchpin of Private Enforcement

As many have recognized, the United States employs litigation as a regulatory tool by allowing private litigants to enforce important statutes in the contexts of antitrust, environmental law, business competition, and employment, among other areas, building what some scholars call a “litigation state.”123Farhang, supra note 13, at 64–65; Kagan, supra note 10, at 6–9; Glover, supra note 10, at 1140. As I argue below, discovery is the lynchpin of this private-enforcement system because it is necessary to enforce these statutory regimes, shapes litigants’ ex ante expectations, structures plaintiffs’ attorneys’ choices, and influences the behavior of regulated entities. While discovery plays this unique role in this enforcement context, it likely lacks the same underlying legitimacy in other cases, like mass torts or state-law claims.

In contrast to European and most other countries, where bureaucracies regulate ex ante, U.S. private litigants enforce the law ex post and without much government involvement. Although plaintiffs pursue their own individual interests in litigation, they promote social welfare by enforcing the law and deterring wrongdoing.124See Lahav, supra note 13; cf. Steven Shavell, The Fundamental Divergence Between the Private and the Social Motive to Use the Legal System, 26 J. Legal Stud. 575, 585 (1997) (explaining that “it may be socially desirable for more to be spent on suit than the amount at stake” when a lawsuit can “create substantial deterrence”). Most importantly, private litigation is a regulatory tool because Congress and courts have deliberately empowered litigants through private rights of action, fee-shifting provisions, and other incentives—thus building a litigation state.125See Burbank & Farhang, supra note 48, at 16; see also Burbank & Farhang, supra note 3, at 15–16. That is, in some of our most important statutes, Congress had the choice whether to create new agencies or rely on plaintiffs through a private right of action. And while in some cases Congress did create agencies like the EPA or FTC, in other statutes Congress instead delegated joint or sole enforcement power to private plaintiffs.126Farhang, supra note 13, at 60, 64–65; Kagan, supra note 10, at 6–9.