Contractual Inequality

Most individuals strive to satisfy every obligation laid out in standard form contracts such as mortgages, insurance plans, or credit agreements. Sophisticated parties, however, adapt and modify their obligations during contract performance by negotiating for lenient treatment and taking advantage of unclear terms. The common law explicitly authorizes variance from standardized contract terms during performance. When the same standard terms create value for sophisticated individuals and destroy value for others, the result is contractual inequality. Contractual inequality has grown without scrutiny by courts or scholars, enabling regressive redistribution of resources and creating economic inefficiency by sowing distrust in markets for consumer contracts.

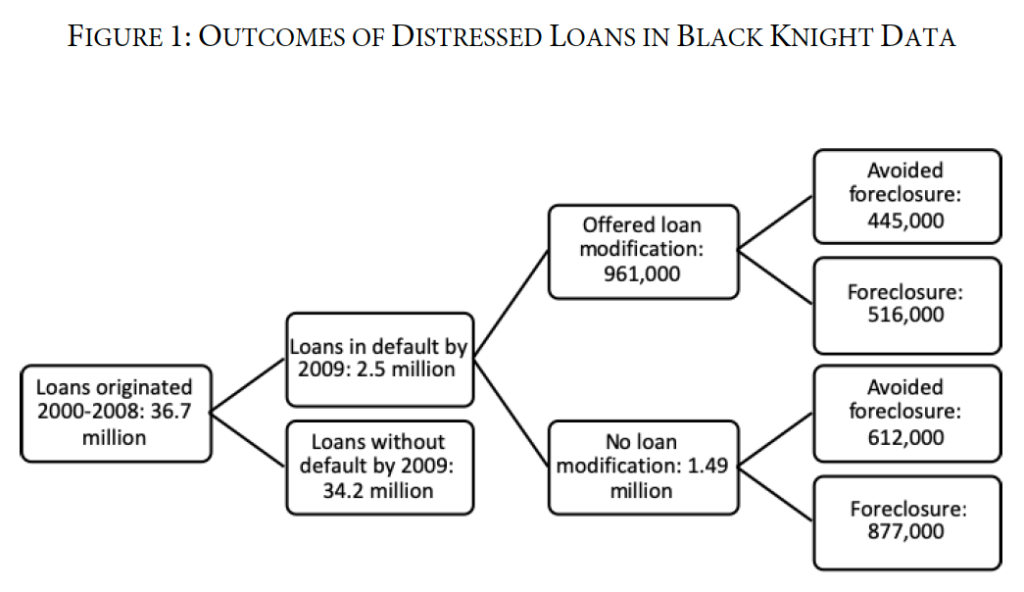

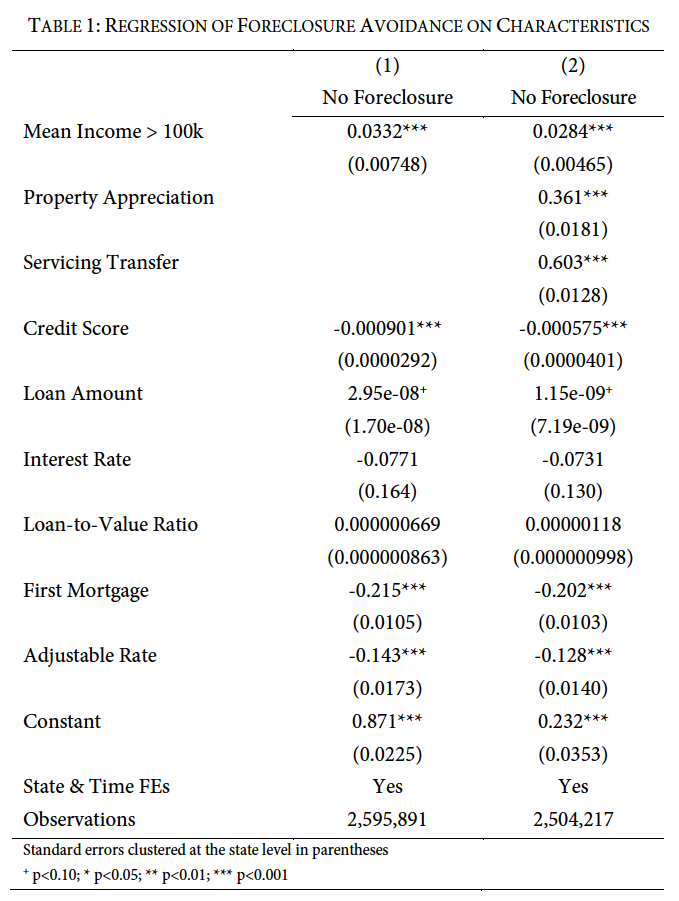

To document the magnitude of contractual inequality, this Article provides novel empirical evidence from a case study of residential mortgage contracts. Data from a large nationwide sample show that many mortgage servicers choose not to utilize their power to foreclose on a borrower in default, with more than one-third of nonpaying borrowers avoiding foreclosure. Servicers disproportionately foreclose on borrowers in poor neighborhoods, regressively redistributing over $500 million in wealth to high-income communities each year. Moreover, servicers’ unfettered freedom to choose who undergoes foreclosure may have reduced the value of mortgages to consumers, increasing market inefficiency.

Courts and regulators need not turn a blind eye to contractual inequality, allowing private market forces to determine the exercise of contract rights. This Article argues that lawmakers should gather information about inequalities in contract performance and disseminate such data to private and public enforcement authorities. By bringing these inequalities to light, lawmakers can take a first step toward more efficient contract markets and a more equal society.

Introduction

Standard form contracts impose equality in contract terms across transactions.1See, e.g., Margaret Jane Radin, Boilerplate: The Fine Print, Vanishing Rights, and the Rule of Law 9 (2013) (“Standardized form contracts, when they are imposed upon consumers, have long been called ‘contracts of adhesion,’ or ‘take-it-or-leave-it contracts,’ because the recipient has no choice with regard to the terms.”); Russell Korobkin, Bounded Rationality, Standard Form Contracts, and Unconscionability, 70 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1203, 1258 (2003) (“[I]n contrast to the Platonic ideal of a contract in which all terms are subject to bargaining, form contracts are usually offered on a take-it-or-leave-it basis—perhaps the price is negotiable, but often even this is not subject to bargaining.”). All mortgage instruments, for instance, borrow their terms from the same federally drafted forms.2Most mortgage contracts include the exact same written terms because of “the huge dominance in the home mortgage market of Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac uniform mortgage instruments.” Julia Patterson Forrester, Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac Uniform Mortgage Instruments: The Forgotten Benefit to Homeowners, 72 Mo. L. Rev. 1077, 1079 (2007); see Fannie Mae Legal Documents (New), Fannie Mae, https://singlefamily.fanniemae.com/fannie-mae-legal-documents#legal-security-instruments [perma.cc/PQ5G-L9DN]. However, standardization in contract terms does not mean that all transactions are equal. Despite assenting to the same terms, different parties may find that contract terms are utilized differently during performance.3This Article builds a theoretical framework on a growing literature emphasizing the difference between the “real deal,” which includes adjustments to the contract after formation, and the “paper deal” in the written contract. A large literature on consumer contracts has discussed the important role played by discretionary benefits, which are usually provided to the consumer by a firm wishing to gain a good reputation despite the formal contract terms being significantly less pro-consumer. See, e.g., Lucian A. Bebchuk & Richard A. Posner, One-Sided Contracts in Competitive Consumer Markets, 104 Mich. L. Rev. 827 (2006); Lisa Bernstein & Hagay Volvovsky, Not What You Wanted to Know: The Real Deal and the Paper Deal in Consumer Contracts—Comment on the Work of Florencia Marotta-Wurgler, 12 Jerusalem Rev. Legal Stud. 128, 131 (2015); Clayton P. Gillette, Rolling Contracts as an Agency Problem, 2004 Wis. L. Rev. 679. The result is that one mortgage borrower may find multiple obligations waived, receiving an easy path to payoff, while a similarly situated borrower may be threatened with legal action at every turn.

This Article develops a theory of inequality in contract performance, rather than inequality in terms offered, across social groups.4This builds on a literature that has illuminated the difference between contracts as written and as enforced. See, e.g., Bebchuk & Posner, supra note 3; Shmuel I. Becher & Tal Z. Zarsky, Minding the Gap, 51 Conn. L. Rev. 69 (2019) (theorizing that firms’ leniency in enforcing consumer contract terms can cause negative consequences for consumers); Meirav Furth-Matzkin, Selective Enforcement of Consumer Contracts: Evidence from the Retail Market (2021) (unpublished manuscript) (on file with the Michigan Law Review) (showing that retail return policies are differentially enforced against different types of customers); Jason Scott Johnston, The Return of Bargain: An Economic Theory of How Standard-Form Contracts Enable Cooperative Negotiation Between Businesses and Consumers, 104 Mich. L. Rev. 857, 864–91 (2006) (noting that differential enforcement of contract terms against parties with different levels of sophistication and bargaining power may have regressive distributional consequences). Differences in performance across identical contracts, termed contractual inequality, have two implications.5See infra Part II. First, they may unfairly privilege sophisticated parties and worsen existing social inequalities.6The primary focus will be on economic inequality, though similar disparities can arise across dimensions such as race, gender, age, sexuality, country of origin, and religion. Economic inequality has been growing exponentially in the last fifty years by many metrics. Thomas Piketty & Emmanuel Saez, Income Inequality in the United States, 1913–1998, 118 Q.J. Econ. 1 (2003) (beginning the modern literature on inequality by collecting comprehensive quantitative data on the growth of inequality in income); Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman, Wealth Inequality in the United States Since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data, 131 Q.J. Econ. 519 (2016) (calculating a broad-based definition of wealth and showing the sudden upturn in wealth inequality starting in the 1980s and continuing to the present day). Second, individuals who are considering entering a new contractual relationship may be deterred by the possibility that they will be mistreated later during performance, resulting in fewer transactions and inefficient prices.7This phenomenon occurs due to incompleteness of contracting, especially due to the inability of contracting parties to credibly commit to not modifying the original contract. Patrick Bolton & Mathias Dewatripont, Contract Theory 37–39 (2005); see also Christine Jolls, Contracts as Bilateral Commitments: A New Perspective on Contract Modification, 26 J. Legal Stud. 203 (1997) (explaining that a particular type of incompleteness, the inability to commit to nonmodifiable contracts, gives rise to welfare loss). Households rely heavily on standardized consumer contracts to secure housing, pay for expenses, and insure against losses, but contractual inequality exposes the most disadvantaged populations to the highest risk of serious loss.8Though consumer contracts touch on a wide variety of settings, including employment, services, retail goods, and online transactions that raise privacy concerns, this Article focuses largely on financial contracts. The largest and most significant contracts undertaken by most households are debt contracts. Household and business indebtedness has grown significantly over the past ten years. See Ctr. for Microeconomic Data, Fed. Rsrv. Bank of N.Y., Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit (2021), https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2021Q3.pdf [perma.cc/ME7F-NH8G]; Joshua Franklin & Kate Duguid, The Decade of Debt: Big Deals, Bigger Risk, Reuters (Dec. 30, 2019, 1:19 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-markets-decade-credit/the-decade-of-debt-big-deals-bigger-risk-idUSKBN1YY09Y [perma.cc/E2GK-2XF5]; Nonfinancial Corporate Business; Debt Securities and Loans; Liability, Level, FRED, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BCNSDODNS [perma.cc/2Q57-PEPP] (last updated Dec. 9, 2021). Saez and Zucman posit that main drivers of wealth inequality include a large growth in debt among low- and middle-income households, Saez & Zucman, supra note 6, at 555, joining Mian and Sufi in their argument that households are dangerously overleveraged. Atif Mian & Amir Sufi, House of Debt: How They (and You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again (2015).

This Article connects fundamental principles of contract law to the growth in economic inequality.9Contract law in this Article refers to the traditional common law of contracts, as well as the set of commercial laws and assorted state and federal regulations targeting the origination and performance of formal contracts. The common law of contracts has traditionally authorized contracting parties to treat social groups differently.10See Oren Bar-Gill, Seduction by Contract 158–64 (2012) (describing the larger harms done to more unsophisticated consumers who are more present-biased when faced with complex contracts intended to take advantage of behavioral biases); Oren Bar-Gill & Elizabeth Warren, Making Credit Safer, 157 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1, 23–25 (2008) (noting that firms with “use-pattern information” about their customers can exploit this knowledge about contract performance to extract value from some customers, usually those who are already disadvantaged in other ways); Tess Wilkinson-Ryan, The Perverse Consequences of Disclosing Standard Terms, 103 Cornell L. Rev. 117 (2017) (suggesting that enhanced disclosure requirements may result in less consumer understanding of the underlying contract terms); Rory Van Loo, Helping Buyers Beware: The Need for Supervision of Big Retail, 163 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1311, 1357–58 (2015) (showing how big retailers’ sales strategies may result in unequal outcomes across consumers). As long as parties satisfy the formal terms of a contract, remaining discretion in contract performance may be used to harm disadvantaged groups and benefit privileged groups.11See Bebchuk & Posner, supra note 3, at 827, 830; Becher & Zarsky, supra note 4, at 77–78; Furth-Matzkin, supra note 4; Johnston, supra note 4, at 859. When the written contract leaves some discretion to the parties, no contract law cause of action exists to challenge unequal treatment during performance.12The law-and-economics literature on embedded options and incomplete contracts has described contracting parties’ inability to bargain in advance for every possible action taken by every party in every possible contingency. Traditional contracts always allocate a certain amount of discretion to the parties that courts are not expected to “verify” and discipline. Robert E. Scott & George G. Triantis, Embedded Options and the Case Against Compensation in Contract Law, 104 Colum. L. Rev. 1428, 1432–33 (2004) [hereinafter Scott & Triantis, Embedded Options]; Robert E. Scott & George G. Triantis, Incomplete Contracts and the Theory of Contract Design, 56 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 187 (2005). Moreover, every consumer contract has some incompleteness, or areas in which contract performance can vary while satisfying formal legal requirements.13A large literature in law and economics on incomplete contracts has noted the significant gaps left in most contracts, but it focuses primarily on courts as gap fillers rather than the parties themselves. See, e.g., Ian Ayres & Robert Gertner, Filling Gaps in Incomplete Contracts: An Economic Theory of Default Rules, 99 Yale L.J. 87, 87, 95 (1989) (proposing an economic theory of gap filling in incomplete contracts); Omri Ben-Shahar, “Agreeing to Disagree”: Filling Gaps in Deliberately Incomplete Contracts, 2004 Wis. L. Rev. 389, 390, 400 (noting that contractual incompleteness can arise in cases of disagreement across parties as well as agreement, meaning that gap filling must avoid exploitation of incompleteness). Exceptions to this include literature on “self-help remedies” in contract, which explicitly refers to the steps parties can take within the bounds of the contract terms to protect their interests. See Mark P. Gergen, A Theory of Self-Help Remedies in Contract, 89 B.U. L. Rev. 1397 (2009) (coining the term “self-help remedies” and canvassing prior literature referring to this concept). For instance, parties are free to exercise their reserved discretion, breach their contracts, waive or enforce their counterparties’ obligations, and modify or renegotiate their agreements without oversight from courts and regulators.14See infra Section I.B. Courts and regulators have granted private parties the right to make these discretionary choices but have turned a blind eye to the use of this power,15See Uri Benoliel & Shmuel I. Becher, Termination Without Explanation Contracts, 2022 U. Ill. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2022), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3737774 [perma.cc/99KN-YHUN] (describing contracting parties’ sometimes arbitrary and erroneous choices while terminating contracts according to the formal terms). allowing contractual inequality to grow unchecked.

This Article takes residential mortgage servicing as a case study for demonstrating the magnitude of contractual inequality. Consider two homeowners who have lost their jobs and cannot make payments on their long-term mortgages.16See Natalie Campisi, Mortgage Delinquencies Spike Due to COVID-19: What to Do If You Can’t Pay Your Loan, Forbes (Aug 18, 2020, 11:05 AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/advisor/2020/08/18/mortgage-delinquencies-spike-due-to-covid-19-what-to-do-if-you-cant-pay-your-loan [perma.cc/U2CT-NYKM]. Both are embedded in their local communities and have children in local public schools. Each calls their mortgage provider and asks for their lender’s cooperation in helping them keep their home.17See How to Negotiate Debts with Your Lenders, Equifax, https://www.equifax.com/personal/education/debt-management/negotiate-debt-with-lenders [perma.cc/3DC8-RWAA]. Though both homeowners have the same credit score and their mortgages have similar interest rates and monthly payments, their two phone conversations proceed very differently. The first homeowner is given several options, including a “loss mitigation” program that can decrease her monthly payments or a short-term “forbearance” period during which she can temporarily stop payment.18For an overview of mortgage options, see Samuel C. Waters, A View from the Trenches: The Legal Practitioner and Loss Mitigation, 60 S.C. L. Rev. 807 (2009). The Federal Trade Commission provides a guide to individuals facing debt collection in other contexts; the guide notes that statutory protections against aggressive debt-collection practices typically do not apply to the original creditor. Debt Collection FAQs, FTC (May 2021), https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/articles/debt-collection-faqs [perma.cc/SA4Q-RJ5J]. The second homeowner, on the other hand, is told that he must pay according to the terms of the mortgage, and he is advised that foreclosure proceedings may begin after four months of missed payments.19See Jeff Ostrowski, Why the Coming Foreclosure Crisis Will Look Nothing Like the Last One, Bankrate (Sept. 1, 2020), https://www.bankrate.com/mortgages/foreclosures-crisis-wont-look-like-great-recession [perma.cc/6TW5-765C]. The first homeowner is ultimately allowed to stay in her home, while the second is forced to remove his children from school and relocate while saddled with a low credit score.20The average mortgage borrower experiences a drop of about 150 points in their credit score once foreclosure proceedings beign. Kenneth P. Brevoort & Cheryl R. Cooper, Foreclosure’s Wake: The Credit Experiences of Individuals Following Foreclosure, 41 Real Est. Econ. 747, 760 (2013).

Using a detailed commercial dataset on mortgage performance, this Article shows how common these disparities are and their devastating effect on consumers. Lenders and servicers making the foreclosure decision have significant discretion over which households face foreclosure rather than less costly alternatives like forbearance. The detailed data used in this Article show that 40% of borrowers who fell behind on their mortgage between 2000 and 2008 avoided foreclosure, largely due to the exercise of discretion by creditors.21See infra Section III.A.1. Moreover, this Article is the first to show that a stark difference exists between creditors’ treatment of borrowers in wealthy neighborhoods relative to those in poorer ones.22See infra Section III.A.2. Loans in high-income neighborhoods are nearly 10% more likely to avoid foreclosure than identical loans in lower-income neighborhoods. The real impacts of foreclosure are widespread—uprooting families, destroying economic value, and negatively impacting communities.23Households, and particularly children, are strongly impacted by foreclosure. See Vicki Been et al., Does Losing Your Home Mean Losing Your School? Effects of Foreclosures on the School Mobility of Children, 41 Reg’l Sci. & Urb. Econ. 407 (2011); Dan Immergluck & Geoff Smith, The Impact of Single-Family Mortgage Foreclosures on Neighborhood Crime, 21 Hous. Stud. 851 (2006); Scott Fay, Erik Hurst & Michelle J. White, The Household Bankruptcy Decision, 92 Am. Econ. Rev. 706 (2002). Both the physical and mental health of households facing foreclosure dropped during the 2008 financial crisis. See Janet Currie & Erdal Tekin, Is There a Link Between Foreclosure and Health?, Am. Econ. J.: Econ. Pol’y, Feb. 2015, at 63; K.A. McLaughlin et al., Home Foreclosure and Risk of Psychiatric Morbidity During the Recent Financial Crisis, 42 Psych. Med. 1441 (2012). Given the high cost of foreclosures, inequality in mortgage performance gives rise to $513 million in losses per year to poor neighborhoods that rich neighborhoods avoid.24See infra Section III.B. Unequal treatment during foreclosure can also sow distrust of servicers that lowers the value of mortgages and creates economic waste.

The Article explains how existing legal regimes and economic incentives are powerless to scrutinize and discipline this type of inequality. Contracting parties have no legal obligation to behave cooperatively with their counterparties as long as they do not breach the contract’s formal terms25See infra Section IV.A. or the common law duty of good faith.26No implied duty in contract law, including the pervasive duty of good faith, has been regularly interpreted to cover the utilization of well-defined contract rights. See infra Section IV.A. Regulators have become more involved in scrutinizing contractual relationships over time, but their power has been tilted toward rulemaking and away from enforcement. The result is that parties’ utilization of contract terms are primarily governed by extralegal forces such as market competition.27This Article sets aside other social and psychological drivers of the behavior of contracting parties. Culture and behavioral factors contribute significantly to decisionmaking within households, and firms and may contribute to unequal treatment of different parties. Economic incentives could contradict these behaviors or reinforce them. Contract law scholars have argued that economic incentives are sufficient to encourage parties to behave cooperatively, with no additional legal oversight needed.28See, e.g., Bebchuk & Posner, supra note 3, at 828; Gillette, supra note 3, at 620. This Article argues, however, that private economic incentives are insufficient in many cases to avoid harmful contractual inequality if transaction costs limit market efficiency.29See infra Section IV.B. Moreover, the private market cannot remedy existing social inequalities, which can occur when there is unequal bargaining power across contracts. For instance, when the same creditor lends to two debtors, one with high reputational influence and the other with little power to influence others, no private market force can prevent the creditor from treating the more powerful debtor better than the less powerful debtor. Private markets cannot discipline inequality without complementary legal mechanisms.30Wealth and income gaps are commonly used to illustrate economic inequality, which can act as a comparator for measuring contractual inequality. E.g., Taylor Telford, Income Inequality in America Is the Highest It’s Been Since Census Bureau Started Tracking It, Data Shows, Wash. Post (Sept. 26, 2019), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/09/26/income-inequality-america-highest-its-been-since-census-started-tracking-it-data-show [perma.cc/5EZ5-9A6T]; James B. Davies, Personal Assets from a Global Perspective, United Nations Univ. World Inst. for Dev. Econ. Rsch.: WIDERAngle (2005), https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/personal-assets-global-perspective [perma.cc/T2NG-PVES] (arguing that both wealth and income must be considered for an accurate picture of economic well-being). Accordingly, income and wealth redistribution via taxation is a popular approach for reducing economic inequality. See Orsetta Causa & Mikkel Hermansen, Income Redistribution Through Taxes and Transfers Across OECD Countries, VoxEU (Mar. 23, 2018), https://voxeu.org/article/income-redistribution-through-taxes-and-transfers [perma.cc/5VL7-JDK8]; Justin Steil, Stephen Menendian & Samir Gambhir, Haas Inst., Responding to Rising Inequality: Policy Interventions to Ensure Opportunity for All 18 (2014), https://belonging.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/HaasInstitute_InequalityPolicyBrief_FINALforDISTRO_2.pdf [perma.cc/F5C7-LBYF] (discussing increased tax rates on estates and capital gains as a tool for addressing inequality).

This Article argues that lawmakers must intervene to bring contractual inequality to the attention of the public. Currently, contracting parties know nothing about how others in their position are treated during performance. Regulators can begin to understand and resolve this problem by requiring disclosure of data regarding contract performance to relevant regulatory authorities and to the public.31See infra Part V. By disclosing the data to sophisticated parties, such as federal agencies, they can be used to facilitate redistribution and redress the distributive harms of contractual inequality.32Taxation is widely considered the most efficient way of redistributing income for the purpose of remedying inequality. Louis Kaplow & Steven Shavell, Why the Legal System Is Less Efficient Than the Income Tax in Redistributing Income, 23 J. Legal Stud. 667, 667–68 (1994). Moreover, data disclosure could provide statistical evidence of inequality in contract performance that disparately impacts protected classes, opening the door to antidiscrimination lawsuits.33Cf. Bethany A. Corbin, Should I Stay or Should I Go? The Future of Disparate Impact Liability Under the Fair Housing Act and Implications for the Financial Services Industry, 120 Penn St. L. Rev. 421, 427–29 (2015). Corbin’s article examines disparate impact litigation under the Fair Housing Act, which was enacted in response to riots spurred by the impact of housing discrimination. Data disclosure may allow for more proactive, tailored legislative responses. Finally, disclosures to private actors such as information aggregators, private regulators, and insurance companies could help private markets hold actors accountable for worsening social inequality.34See infra Part V. Recognizing and addressing contractual inequality is essential for lawmakers to sustainably serve the needs of all types of contracting parties.

The Article proceeds as follows. Part I introduces contractual inequality and its potential harms, focusing on negative distributional effects and inefficiency. Part II describes how contract law worsens inequality, including traditional embedded options in contracts such as the exercise of reserved discretion, waiver, enforcement, modification, renegotiation, and breach. Part III introduces residential mortgage contracts as an empirical setting to demonstrate the magnitude of inequality in contract outcomes. Part IV lays out the limitations of using existing tools to oversee contractual inequality. Part V suggests disclosure reforms tailored to minimizing the negative impacts of contract law on social inequality and maximizing the efficiency of contract markets.

I. Inequality in Contract Performance

Boilerplate contracts are essential to households’ income, education, and long-term financial well-being.35Many important standardized contracts for households are debt instruments, with mortgages, credit card agreements, and student loans relying on standardized forms. See, e.g., Bar-Gill, supra note 10, at 1–4. Household debt is at an all-time historical high and is continuing to increase. See Bd. of Governors of the Fed. Rsrv. Sys., Financial Stability Report 32 (2021) [hereinafter Financial Stability Report], https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/financial-stability-report-20211108.pdf [perma.cc/S6LF-4WC6]. Contract terms, however, are written in legal language that ordinary individuals cannot understand.36See Yannis Bakos, Florencia Marotta-Wurgler & David R. Trossen, Does Anyone Read the Fine Print? Consumer Attention to Standard-Form Contracts, 43 J. Legal Stud. 1, 3 (2014) (finding that only 0.2% of software shoppers read end-user license agreements for one second or longer); Florencia Marotta-Wurgler, Some Realities of Online Contracting, 19 Sup. Ct. Econ. Rev. 11, 12 (2011) (“Like their brick-and-mortar counterparts, online sellers typically offer take-it-or-leave-it standard form contracts.”); Shmuel I. Becher & Uri Benoliel, The Duty to Read the Unreadable, 60 B.C. L. Rev. 2255 (2019) (using linguistic methods to show that contracts are as difficult to read as academic articles and concluding they exclude the typical consumer); cf. David A. Hoffman, Relational Contracts of Adhesion, 85 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1395, 1403 (2018) (discussing the growth of plain English contracts by big companies intended to improve subjective consumer understanding). Vanishingly few consumer contracts include negotiated terms; instead, businesses offer exactly identical contracts to multiple consumers.37See Radin, supra note 1, at 7–9 (describing the proliferation of standard form contracts and the inability of consumers to find more favorable terms elsewhere); Bakos et al., supra note 36, at 1–2 (describing how in “untold billions of commercial transactions,” buyers are “presented with a preprinted form contract . . . with little opportunity to negotiate the terms”). Even sophisticated parties who hire big law firms often find that their contract terms are identical to those used in other transactions.38See Mitu Gulati & Robert E. Scott, The Three and a Half Minute Transaction: Boilerplate and the Limits of Contract Design 6 (2013) (describing the big law firm business model as one that “relies on herd behavior, fails to provide incentives for innovation and thus rises and falls on volume-based, cookie-cutter transactions”); Julian Nyarko, Stickiness and Incomplete Contracts, 88 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1, 3–7 (2021) (finding that even in the most sophisticated, high-dollar value transactions, big law firms rely on templates that may not include provisions that would be important to the transaction, such as the lack of choice-of-forum provision that harmed Sprint in the Sprint-Nextel merger). But cf. Adam B. Badawi, Scott D. Dyreng, Elisabeth de Fontenay & Robert W. Hills, Contractual Complexity in Debt Agreements: The Case of EBITDA, SSRN (May 7, 2021), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3455497 (showing significant personalization in commercial debt clauses defining accounting procedures, intended to strategically improve perceived financial health). A large fraction of the contract language is taken from other sources, including previous contracts written for similar transactions, forms drafted by law firms, and recommended language suggested by professional associations.39See Gulati & Scott, supra note 38, at 10 (noting the “ready availability of prefabricated contracts” in today’s legal practice, resulting in “[f]ar too much of the revealed text [being] preserved in each new incarnation of the document”); Claire A. Hill, Why Contracts Are Written in “Legalese,” 77 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 59, 59–60 (2001) (discussing law firm use of forms); Nyarko, supra note 38, at 1 (finding that “external counsel rely heavily on templates” and that “[t]here is no evidence to suggest that counsel negotiate over the inclusion of dispute resolution clauses, nor that law firm templates are revised in response to changes in the costs and benefits of incomplete contracting”); Joseph M. Perillo, Keynote Address, Neutral Standardizing of Contracts, 28 Pace L. Rev. 179, 182–85 (2008) (noting the proliferation of standardized contracts drafted by professional associations in the business-to-business context). Written contracts therefore reflect historical custom and the psychology of the drafters more than the relevant details of a particular transaction.40See Bar-Gill, supra note 10, at 2–3 (discussing the interaction between market forces and consumer psychology and noting that “competition forces sellers to exploit the biases and misperceptions of their customers” in the way they present their contracts); Gulati & Scott, supra note 38, at 33–43 (describing theories of boilerplate stickiness, many of which rely on custom and psychologically biased thinking); Hill, supra note 39, at 61–62, 73–75 (finding that psychological dynamics at play in contract drafting “represent departures from ‘rationality,’ as that term commonly is used in economics”); Nyarko, supra note 38, at 25 (noting that one explanation for lawyers’ failure to change their templates is that lawyers “may be risk averse and afraid of the unknown scenarios that may unfold if the templates are tampered with, ultimately leading to a status quo bias”).

Standardized “contracts of adhesion” signed by parties with unequal sophistication, such as a consumer and a firm, have concerned scholars for decades.41E.g., Todd D. Rakoff, Contracts of Adhesion: An Essay in Reconstruction, 96 Harv. L. Rev. 1173 (1983) (proposing that standard form contracts be held presumptively unenforceable on the theory that the power imbalance between parties has negative consequences for the integrity of contract law as a whole). Because the consumer has relatively little power to negotiate and understand the contract terms, standard form contracts may contain terms that are one sided in favor of the firm. If a dispute arises, the more powerful firm is likely to prevail, ultimately decreasing the value of the contract to the less powerful consumer. To combat these harms, scholars have argued for more informed assent, careful drafting procedures, and judicial and regulatory measures to improve the quality of standard form contracts.42E.g., Ian Ayres & Alan Schwartz, The No-Reading Problem in Consumer Contract Law, 66 Stan. L. Rev. 545, 579–90 (2014) (proposing that regulators mandate a system of disclosures that would increase consumer understanding by highlighting unexpected terms and that courts should only enforce terms that consumers can be expected to understand); Bar-Gill, supra note 10, at 4–5 (arguing for disclosure regulation that would increase consumer ability to make better choices); Stephen J. Choi, Mitu Gulati & Robert E. Scott, The Black Hole Problem in Commercial Boilerplate, 67 Duke L.J. 1, 68 (2017) (“[C]ourts should be open to arguments that, as a matter of law, the clause in question has been emptied of meaning and functions as a black hole in the boilerplate.”); Nyarko, supra note 38, at 74 (arguing that legal education should better prepare law students to challenge and re-evaluate standard form contracts). Regarding consumer financial contracts in particular, these concerns have spurred the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to ensure that consumers assent to high-quality financial contracts.43Bar-Gill & Warren, supra note 10.

This Article focuses on a different issue with this market—the performance of standard form contracts. Transactions subject to the same terms evolve differently during performance as circumstances change, new information becomes available, and parties make decisions.44Contract law makes provision for these types of changes with doctrines of excuse, modification, and others. David V. Snyder, The Law of Contract and the Concept of Change: Public and Private Attempts to Regulate Modification, Waiver, and Estoppel, 1999 Wis. L. Rev. 607. At the completion of the contract term, decisions made about performance mutate the written contract’s “paper deal” into very different “real deals” for different transactions.45See, e.g., Becher & Zarsky, supra note 4. Contractual inequality occurs when two similar transactions with similarly situated parties end with different outcomes due to decisions made during performance.

Consider the example of two families trying to build their wealth. Each has a savings account at a local bank, where their paychecks are directly deposited and their bills are automatically paid each month. The system breaks down when their paychecks are delayed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both families are charged an overdraft fee of $225 when their bills are paid without sufficient funds in the account.46CFPB, CFPB Study of Overdraft Programs: A White Paper of Initial Data Findings 23 (2013), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201306_cfpb_whitepaper_overdraft-practices.pdf [perma.cc/B8T8-BM9F]. At this point, their experiences diverge. The first family waits until the paycheck is deposited and calls the bank about the overdraft fee. The bank representative explains that they themselves opted into the overdraft protection program and that the standard fee is $225.47Id. at 27–31. Ultimately, they pay the overdraft fee along with the other bills after their paycheck is processed. The second family calls the bank and complains about the charge. By asking to speak with a manager and threatening to post negative reviews of the bank on social media, they manage to get the overdraft fee waived.48Id. at 52. This pattern repeats itself over the course of the pandemic, leaving the first family thousands of dollars poorer than the second.

This example highlights two key features of contractual inequality. First, the two transactions were largely similar until the overdraft fee was levied, with identical formal terms in each contract. Therefore, the literature on assent and consumer understanding of contract terms does not shed light on how and why the two families’ experiences diverged. Second, the divergence may occur for any reason and need not be driven by animus or intent to harm the consumer. The second family may simply have had a more aggressive negotiating strategy, have been advised by a lawyer, or have promised the bank more business if they waived the fee. On the other hand, the bank representative may have been swayed by gender or racial bias.49See, e.g., Ian Ayres, Fair Driving: Gender and Race Discrimination in Retail Car Negotiations, 104 Harv. L. Rev. 817 (1991). Each of these explanations raises different concerns. Regardless, contractual inequality causes two types of harms.

First, in common with other settings, unequal treatment may be inherently undesirable. For instance, contractual inequality can worsen existing disparities across social groups, resulting in regressive redistribution or impermissible disparate impact. Second, unequal treatment generates economic inefficiency. Individuals who are considering entering into a standardized contract are aware that once the contract is signed, the company is free to stringently enforce the contract with them, while other customers are treated cooperatively and leniently. Consumers therefore may rationally distrust companies offering standard form contracts, ultimately choosing not to participate in key contracts because the law does not protect them against the risk of loss during performance. This phenomenon arises due to a commitment problem inherent to contract law, which does not allow parties to contract out of waiver, the exercise of discretion, modification, renegotiation, and breach. Consequently, inequality is particularly harmful in the contracts context. Each of these harms is discussed in turn below.

A. Regressive Redistribution

Social inequality has grown significantly in the last few decades.50Piketty & Saez, supra note 6; The 2017 Tax Law and Who It Left Behind: Hearing Before the H. Comm. on Ways & Means, 116th Cong. 14 (2019) (statement of Elise Gould, Senior Economist, Economic Policy Institute) (explaining that the difference between incomes of lower-class and upper-class Americans is consistently increasing); U.N. Dep’t of Econ. & Soc. Affs., World Social Report 2020: Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World, at 3, U.N. Doc. ST/ESA/372, U.N. Sales No. E.20.IV.1 (2020), https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3847753?ln=en [perma.cc/GA35-HJQX] (“[I]nequality has increased in most developed countries and in some middle-income countries . . . since 1990.”); Janet L. Yellen, Chair, Bd. of Governors of the Fed. Rsrv. Sys., Perspectives on Inequality and Opportunity from the Survey of Consumer Finances 1 (Oct. 17, 2014), https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/files/yellen20141017a.pdf [perma.cc/78D4-YBV4] (“The distribution of income and wealth in the United States has been widening more or less steadily for several decades, to a greater extent than in most advanced countries.”). But see Ana Revenga & Meagan Dooley, Is Inequality Really on the Rise?, Brookings Inst. (May 28, 2019), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2019/05/28/is-inequality-really-on-the-rise [perma.cc/X3VB-3JKW] (stating that although within-country inequality has increased in nations with advanced economies, total global inequality has declined since the 1990s as poor countries become wealthier). High-income households have seen their income grow at four times the rate of low-income households in the last twenty years.51Higher-income households have an average income that is 8% higher than their analogues twenty years ago, while lower-income households have seen their income increase by less than 2%. See Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik & Rakesh Kochhar, Pew Rsch. Ctr., Most Americans Say There Is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., but Fewer Than Half Call It a Top Priority 15 (2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/01/PSDT_01.09.20_economic-inequailty_FULL.pdf [perma.cc/V549-8KGV]. The large disparity in standards of living and opportunities for social mobility between rich and poor households was highlighted by the 2009 recession and gave rise to the Occupy Wall Street movement.52See Emily Stewart, We Are (Still) the 99 Percent, Vox (Apr. 30, 2019, 9:00 AM), https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/4/23/18284303/occupy-wall-street-bernie-sanders-dsa-socialism [perma.cc/QTS7-8RB6]. Occupy Wall Street formed in 2011 as a protest against the unchecked power of large financial institutions and the economic disparities that this power perpetuates. About, Occupy Wall Street, http://occupywallst.org/about [perma.cc/FB5A-S3ND]; Mattathias Schwartz, Pre-Occupied: The Origins and Future of Occupy Wall Street, New Yorker (Nov. 20, 2011), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/11/28/pre-occupied [perma.cc/5QB7-YDD3]. As evidenced by its “We Are the 99 Percent” tagline, the movement was mainly focused on drawing attention to economic inequality and airing the grievances of nonwealthy Americans, rather than advocating for specific policy changes. Amy Dean, Occupy Wall Street: A Protest Against a Broken Economic Compact, Harv. Int’l Rev., Spring 2012, at 12, 12–13. Although most Occupy Wall Street events dissipated by 2012, the movement brought economic inequality to the forefront of national conversations and hugely influenced mainstream politics. Stewart, supra (discussing the long-term impact of Occupy Wall Street); Arindrajit Dube & Ethan Kaplan, Occupy Wall Street and the Political Economy of Inequality, Economists’ Voice, March 2012, at 1, 4–5, https://doi.org/10.1515/1553-3832.1899 (describing Occupy Wall Street’s influence on public policy). Since then, a significant movement among politicians, activists, and voters has given a national stage to policy debates directly addressing inequality.53Several politicians in the Democratic Party have made reducing social inequality a prominent component of their platforms. See, e.g., Annie Grayer, Bernie Sanders Releases Tax Plan to Target Income Inequality, CNN (Sept. 30, 2019, 8:03 AM), https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/30/politics/bernie-sanders-tax-plan-income-inequality/index.html [perma.cc/Z9UE-UYEC]; Kevin Breuninger & Tucker Higgins, Elizabeth Warren Proposes ‘Wealth Tax’ on Americans with More Than Million in Assets, CNBC (Jan. 25, 2019, 9:10 AM), https://www.cnbc.com/2019/01/24/elizabeth-warren-to-propose-new-wealth-tax-economic-advisor.html [perma.cc/7BMG-44ZU]; Jessica Corbett, ‘A Just Society’: Ocasio-Cortez Unveils Legislative Package to Tackle American Poverty and Inequality, Common Dreams (Sept. 25, 2019), https://www.commondreams.org/news/2019/09/25/just-society-ocasio-cortez-unveils-legislative-package-tackle-american-poverty-and [perma.cc/48PS-SGET]; Maggie Astor et al., 6 Takeaways from the Biden-Sanders Joint Task Force Proposals, N.Y. Times (July 9, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/09/us/politics/biden-sanders-task-force.html [perma.cc/A7TZ-Y3EC] (describing President Biden’s policy proposals aimed at reducing economic and racial inequality). The global pandemic of 2020 highlighted how little progress has been made in remedying inequality, with low-paid essential workers risking their lives to supply the needs of much more affluent at-home workers.54Aaron van Dorn, Rebecca E. Cooney & Miriam L. Sabin, COVID-19 Exacerbating Inequalities in the US, 395 Lancet 1243, 1243 (2020) (describing COVID-19’s disproportionately large impact on racial minorities and economically disadvantaged communities); Catherine Thorbecke & Arielle Mitropoulos, ‘Extreme Inequality Was the Preexisting Condition’: How COVID-19 Widened America’s Wealth Gap, ABC News (June 28, 2020, 11:42 AM), https://abcnews.go.com/Business/extreme-inequality-preexisting-condition-covid-19-widened-americas/story?id=71401975 [perma.cc/653N-YT87] (illustrating that the coronavirus crisis has resulted in the ultrarich getting richer and the bottom 40% of earners getting poorer). Policy remedies have been difficult to find, in part due to the complex sources of the problem, including long-standing historical factors surrounding race and communities, systemic failures in public education, and misaligned economic incentives.55Historical policies that limited lending in certain neighborhoods based on race, known as redlining, continue to contribute to racial segregation and adversely affect the wealth of nonwhite neighborhoods. See Amy Scott, Inequality by Design: How Redlining Continues to Shape Our Economy, Marketplace (Apr. 16, 2020), https://www.marketplace.org/2020/04/16/inequality-by-design-how-redlining-continues-to-shape-our-economy [perma.cc/CY5X-E3U3]. Moreover, children in poor communities have fewer educational opportunities and show diminished academic performance, perpetuating systemic inequalities. Emma García & Elaine Weiss, Econ. Pol’y Inst., Educational Inequalities at the School Starting Gate (2017), https://files.epi.org/pdf/132500.pdf [perma.cc/3VEW-ABSX]. Finally, minorities and women are discouraged from pursuing highly paid and skilled work due to discrimination, lack of human capital, and preference. Chang-Tai Hsieh, Erik Hurst, Charles I. Jones & Peter J. Klenow, The Allocation of Talent and U.S. Economic Growth, 87 Econometrica 1439 (2019); see also Danyelle Solomon, Connor Maxwell & Abril Castro, Ctr. for Am. Progress, Systematic Inequality and Economic Opportunity 1 (2019), https://cf.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/StructuralRacismEconOpp-report.pdf [perma.cc/E358-74QK] (“Eliminating current disparities among Americans will require intentional public policy efforts to dismantle systematic inequality . . . .”). Most policies targeting inequality have focused on direct redistribution of wealth from rich to poor, usually through taxes and social welfare programs.56See Kaplow & Shavell, supra note 32, at 667.

Legal scholars have focused on the role of law in the creation and exacerbation of harmful social inequality.57This discourse typically focuses on the existence of social inequality across various sociological classes, as well as the growth of economic inequality in recent decades. E.g., Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Arthur Goldhammer trans., Harv. Univ. Press 2014) (2013). Discourse on social inequality has heavily influenced and been influenced by social movements and significant events like the 2008 financial crisis. See, e.g., Sarah Gaby & Neal Caren, The Rise of Inequality: How Social Movements Shape Discursive Fields, 21 Mobilization 413, 413–14 (2016) (arguing that political movements such as Occupy Wall Street have increased public discourse and awareness of social inequality); Leanne S. Giordono, Michael D. Jones & David W. Rothwell, Social Policy Perspectives on Economic Inequality in Wealthy Countries, 47 Pol’y Stud. J. S96 (2019) (explaining that the 2008 financial crisis led to an increased interest in social inequality among public policy scholars). Economic, gender, and racial inequality have been aggravated by differential use of legal tools against social groups. The criminal justice system, administrative agencies, and other public actors have been heavily studied by scholars58See, e.g., Richard B. Stewart, The Reformation of American Administrative Law, 88 Harv. L. Rev. 1667, 1682–83 (1975) (studying discretion in administrative decisionmaking and its effect on interest-group pressures); Robert Heller, Comment, Selective Prosecution and the Federalization of Criminal Law: The Need for Meaningful Judicial Review of Prosecutorial Discretion, 145 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1309, 1329–31 (1997) (discussing the high level of discretion available to prosecutors and arguing for oversight by judges); Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (10th anniversary ed. 2020) (reframing disparate impact in the criminal system as a deliberate mechanism for subordinating minority races by the differential usage of incarceration). and regulated by lawmakers59Mandatory minimums were originally instituted in response to calls of racial discrimination by judges in the sentencing process:

For decades, racial and other “legally unwarranted” disparities in sentencing have been the subject of considerable empirical research, which has in turn helped to shape major policy changes. Most importantly, the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines and their state counterparts were adopted with the goal of reducing such disparities. In 2005, when the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Booker rendered the formerly mandatory Guidelines merely advisory, Justice Stevens’s dissent predicted that “[t]he result is certain to be a return to the same type of sentencing disparities Congress sought to eliminate in 1984.”

Sonja B. Starr & M. Marit Rehavi, Mandatory Sentencing and Racial Disparity: Assessing the Role of Prosecutors and the Effects of Booker, 123 Yale L.J. 2, 4–5 (2013) (quoting United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220, 300 (2005) (Stevens, J., dissenting in part)). However, mandatory minimums ultimately worsened discrimination by prosecutors. See id. at 71. as a source of social inequality. Public law scholars have a deep interest in the differential understanding of how legal institutions interact differently with the rich and the poor.60Constitutional law scholars have argued that socioeconomic class should be a “suspect classification” under the Equal Protection Clause. See, e.g., Mario L. Barnes & Erwin Chemerinsky, The Disparate Treatment of Race and Class in Constitutional Jurisprudence, Law & Contemp. Probs., Fall 2009, at 109; Bertrall L. Ross II & Su Li, Measuring Political Power: Suspect Class Determinations and the Poor, 104 Calif. L. Rev. 323 (2016). Criminologists have heavily investigated the “criminalization of poverty,” referring to the phenomenon where the inability to pay is evidence of criminal culpability in a variety of contexts. See, e.g., Kaaryn Gustafson, The Criminalization of Poverty, 99 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 643, 646 n.12 (2009) (emphasis omitted). Research on access to justice has highlighted that providing the opportunity to litigate may benefit the most powerful to the detriment of the weak.61Omri Ben-Shahar, The Paradox of Access Justice, and Its Application to Mandatory Arbitration, 83 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1755 (2016). Even differences in contract formation between genders and racial groups have been studied and litigated as having an impermissible disparate impact on protected classes.62For a summary of this literature and litigation, see Peter P. Swire, The Persistent Problem of Lending Discrimination: A Law and Economics Analysis, 73 Tex. L. Rev. 787 (1995).

Contractual inequality refers to a less-studied disparate impact—differences in value created by contract performance across social groups.63Literature in consumer law, particularly focusing on predatory lending, has created frameworks for thinking about the distributional implications of contract formation. Existing work focuses on the formation of contracts that are onerous or abusive, while this Article looks at contract performance. See, e.g., Abbye Atkinson, Rethinking Credit as Social Provision, 71 Stan. L. Rev. 1093, 1154–57 (2019) (describing how private debt supplanted social insurance); Kathleen C. Engel & Patricia A. McCoy, A Tale of Three Markets: The Law and Economics of Predatory Lending, 80 Tex. L. Rev. 1255, 1270–98 (2002) (discussing the role of predatory lending in financing home purchases and other large household expenditures). Among consumers subject to the same contract terms, for example, some may consistently be treated well while others are treated poorly.64See, e.g., Furth-Matzkin, supra note 4, at 9–10. Disparities in contract performance are particularly important to deter and remedy due to contracts’ essential role in facilitating the exchange of labor for income, the accumulation of savings, and the purchase of consumer goods, education, investments, and other assets.

Disparities in performance may be particularly harmful if they are regressive. For instance, suppose the bank customer whose overdraft fee was not waived is Black and poor. The unequal treatment meted out by the bank adds to the list of obstacles facing poor and Black individuals trying to build wealth.65For an overview of the evidence on the racial wealth gap, see Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede & Sam Osoro, Inst. on Assets & Soc. Pol’y, The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide (2013), https://heller.brandeis.edu/iere/pdfs/racial-wealth-equity/racial-wealth-gap/roots-widening-racial-wealth-gap.pdf [perma.cc/KGP8-L829]. Since the Black family is part of a protected class, the bank’s conduct could even violate federal antidiscrimination law.66See Peter E. Mahoney, The End(s) of Disparate Impact: Doctrinal Reconstruction, Fair Housing and Lending Law, and the Antidiscrimination Principle, 47 Emory L.J. 409 (1998), for a discussion of disparate impact and the difficulty in proving claims of disparate impact. Though bank overdraft fees have been widely studied and regulated, regulators do not quantitatively assess how many fees are waived for Black customers relative to others.67Another example of this is the generic guidance provided during COVID-19 to waive overdraft fees. Despite this guidance, many banks profited significantly from overdraft fees during the pandemic. Bd. of. Governors of the Fed. Rsrv. Sys., Fed. Deposit Ins. Corp. & Off. of the Comptroller of the Currency, Joint Statement on CRA Consideration for Activities in Response to COVID-19 (Mar. 19, 2020), https://www.fdic.gov/news/financial-institution-letters/2020/fil20019a.pdf [perma.cc/QUT3-ERQW]; Annie Nova, Banks Will Collect More Than Billion in Overdraft Fees This Year. Here’s How to Avoid Them, CNBC (Dec. 1, 2020, 5:31 PM), https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/01/banks-will-get-30b-in-overdraft-fees-this-year-heres-how-to-avoid-them-.html [perma.cc/97U9-BEKG].

It is essential to note that disparate treatment may be economically rational. For instance, the bank could rationally believe that the second family’s threat to tweet about the company’s behavior would lose them more money than the lost overdraft fee. Or the bank may have noticed that aggressive overdraft-fee negotiators bring more business to the bank, making it profitable to keep those customers happy. The bank may not even be aware of the individual’s gender, race, or wealth. The distributive harm remains in this case, however, since there is a disparate impact on underprivileged populations.

Moreover, economic efficiency cannot always justify contractual inequality because even sophisticated parties sometimes make inefficient choices, resulting in arbitrary performance inequalities.68Consider, for example, drafting errors in boilerplate. See Gulati & Scott, supra note 38, at 150. A large legal literature has demonstrated that legal actors making discretionary choices are influenced by behavioral factors. For example, a famous study found that judges were more lenient in cases heard early in the day, with leniency dropping significantly until judges had a lunch break.69Shai Danziger, Jonathan Levav & Liora Avnaim-Pesso, Extraneous Factors in Judicial Decisions, 108 PNAS 6889, 6890–92 (2011). Note that the size of the effect was challenged by Andreas Glöckner, The Irrational Hungry Judge Effect Revisited: Simulations Reveal That the Magnitude of the Effect Is Overestimated, 11 Judgment & Decision Making 601 (2016). Increasing discretion awarded to prosecutors in charging decisions and judges in criminal sentencing led to larger disparities in sentences between Black and white defendants.70See, e.g., Jon Sorensen & Donald H. Wallace, Prosecutorial Discretion in Seeking Death: An Analysis of Racial Disparity in the Pretrial Stages of Case Processing in a Midwestern County, 16 Just. Q. 559 (1999); Robert J. Smith & Justin D. Levinson, The Impact of Implicit Racial Bias on the Exercise of Prosecutorial Discretion, 35 Seattle U. L. Rev. 795 (2012); Crystal S. Yang, Free at Last? Judicial Discretion and Racial Disparities in Federal Sentencing, 44 J. Legal Stud. 75 (2015). Individuals are not the only decisionmakers subject to these inefficient impacts. The literature on discretion in administrative lawmaking finds evidence that agencies make decisions that are biased in favor of interest groups and lobbies.71See, e.g., Anthony M. Bertelli & Christian R. Grose, Secretaries of Pork? A New Theory of Distributive Public Policy, 71 J. Pol. 926 (2009) (showing empirical evidence that administrative discretion can result in discretionary redistribution).

The legal system is indirectly responsible for distributional harms of contractual inequality because the threat of court enforcement limits parties’ ability to walk away from their contractual obligations. Contracts scholars have argued that contract law can act as a powerful force for progressive redistribution at formation, including the use of unconscionability and other principles to protect vulnerable contracting parties.72Eric A. Posner, Contract Law in the Welfare State: A Defense of the Unconscionability Doctrine, Usury Laws, and Related Limitations on the Freedom to Contract, 24 J. Legal Stud. 283 (1995). However, these doctrines do not typically extend to contract performance, leading to worsening inequality.

B. Inefficiency of Incomplete Contracts

A more subtle, but potentially more destructive, harm can arise from inequality in contract performance. Parties who anticipate unequal treatment and fear that they may be in the group that incurs losses due to their counterparty’s decision will expect diminished value from the contract. As a result, they may face inefficiently high prices. Moreover, the fear of being treated uncooperatively during performance may make already disadvantaged groups choose to opt out of the market. This chilling effect arises from the fact that contracts are incomplete, meaning that firms have many options to modify the performance of contracts, with the decisions made during performance potentially leading to widespread economic loss.73Contracts do not—and often should not—specify the full set of actions parties should take in every contingency. See B. Douglas Bernheim & Michael D. Whinston, Incomplete Contracts and Strategic Ambiguity, 88 Am. Econ. Rev. 902 (1998). Moreover, parties cannot commit to taking certain actions, such as avoiding modification upon mutual agreement. Jolls, supra note 7. For empirical studies on this subject, see Patrick Bajari & Steven Tadelis, Incentives Versus Transaction Costs: A Theory of Procurement Contracts, 32 RAND J. Econ. 387 (2001), and Sarath Sanga, Incomplete Contracts: An Empirical Approach, 34 J.L. Econ & Org. 650 (2018).

Returning to the example of banking, consider how new bank customers may behave in light of overdraft fee policies. More than 5% of American households have no bank account, limiting their access to a variety of financial benefits such as low-cost checking, direct deposits, and access to fairly priced loans.74See Mark Kutzbach, Alicia Lloro & Jeffrey Weinstein, Fed. Deposit Ins. Corp., How America Banks: Household Use of Banking and Financial Services 12 (2020), https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/household-survey/2019report.pdf [perma.cc/B53V-TLU9]. Unbanked individuals may hear of stories like the one above and decide that the risk of incurring overdraft fees is high enough that they will only open a bank account when offered a bonus, despite the hidden costs associated with these “perks.”75Bonuses are rarely giveaways, and consumers may be hit with back-end fees that cost more than the bonus provided. See, e.g., Margarette Burnette, Alice Holbrook & Ruth Sarreal, Bank Sign-Up Bonuses: 5 Things to Look Out For, Nerdwallet (Dec. 13, 2021), https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/banking/5-reasons-ignore-bank-signup-bonuses [perma.cc/3EVR-M7NA]. Even worse, disadvantaged populations such as Black or immigrant families may realize that they are less likely to receive waivers and choose not to open a bank account at all, relying on expensive check-cashing services.76Indeed, Black families are much less likely to participate in the formal financial market than other racial groups. See generally Mehrsa Baradaran, The Color of Money (2017) (discussing the harms and effects of the racial wealth gap and segregated economy). Economically efficient transactions that could have occurred in the absence of performance inequality are undermined by the possibility that firms will treat groups unequally.

Note that contract incompleteness causes harm in two ways. First, it can lead to inefficient pricing and quality in markets for consumer contracts.77See Bengt Holmström, Moral Hazard and Observability, 10 Bell J. Econ. 74, 79 (1979). Exceptional customer service and other hallmarks of high-quality contract performance cannot be guaranteed. Therefore, rational customers will refuse to pay full price for these amenities, and companies will be less likely to provide perks during contract performance. If firms could credibly commit to cooperating with their customers during breakdown of the relationship, the transaction would be more valuable. Second, the expectation of uncooperative behavior from firms can lead the market for consumer contracts to dwindle in trade volume and even die out in certain markets.78Id. at 87. Some contracts may include too much risk for consumers to participate. The harm here arises from a value-creating trade that did not occur—if the consumer could be assured of good treatment, they would participate in the market, improving both their own and their counterparty’s bottom line. Contractual inequality could result in disadvantaged populations leaving markets for consumer contracts to the detriment of the entire economy.

Can incompleteness be eliminated by changing contract design? The gap between formal contracts as drafted and the economic value generated by the relationship arises from discretion in the hands of contracting parties. Written contracts do not specify the actions parties should take in every contingency, instead leaving the contract terms incomplete, waiting to be filled in by the parties or the courts. Economists have shown that it may be optimal to structure contracts in this way because gaps in a contract’s specification of rights or obligations can increase the value generated by a contractual relationship by allowing parties to tailor the contract to unexpected situations that arise during the contract term.79See Bernheim & Whinston, supra note 73, at 920. Moreover, parties to a contract can take advantage of incompleteness to make dynamic adjustments to the contract during the course of performance.80See, e.g., Gillian K. Hadfield, Problematic Relations: Franchising and the Law of Incomplete Contracts, 42 Stan. L. Rev. 927 (1990) (explaining the interplay between discretionary choices within incomplete contracts and the interpretation of formal contract terms). Legal scholarship typically looks to courts to fill these gaps.81Default rules are typically thought to fill gaps in incomplete contracts, since parties can contract away from the default. This account has been challenged, however, due to the cost of contracting away from defaults. See Ayres & Gertner, supra note 13; Omri Ben-Shahar & John A.E. Pottow, On the Stickiness of Default Rules, 33 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 651 (2006). However, most incompleteness is resolved by unilateral or joint action by the parties before courts get involved in contract disputes.82See, e.g., Bernstein & Volvovsky, supra note 3, at 129–31; Hadfield, supra note 80. How parties fill these gaps determines the inequality the contract will generate.

Insurance contracts, for instance, are fraught with incompleteness.83E.g., Jean‐Marc Bourgeon & Pierre Picard, Insurance Law and Incomplete Contracts, 51 RAND J. Econ. 1253, 1253 (2020) (“[T]he link between the circumstances of the claim and the indemnity payment is rarely specified in detail in the insurance contract, and it is often limited to exclusions or force majeure clauses. In other words, more often than not, insurance contracts are incomplete.” (footnote omitted)). The contract may specify the general outlines of coverage, but no contract can specify every detail of a particular claim. In theory, insurers could offer a contract that specified the precise documentation required of every claimant before being paid. The company may still choose to waive those conditions and pay the claim without full documentation.84See, e.g., Bebchuk & Posner, supra note 3; Becher & Zarsky, supra note 4; Furth-Matzkin, supra note 4; Johnston, supra note 4. Therefore, it is both too costly and likely unappealing to specify the insurer’s course of action in every conceivable scenario. Instead, some discretion is afforded to the parties in the language of the contract. The insurer can decide how exactly to administer claims, when to pay out, and how much coverage to award in each situation to fill the gaps in the contract language.85Scholars have discussed contractual inequality in the insurance context more than in others, with Schwarcz proposing a similar disclosure remedy to the one in this Article. Daniel Schwarcz, Transparently Opaque: Understanding the Lack of Transparency in Insurance Consumer Protection, 61 UCLA L. Rev. 394, 414–20 (2014).

Despite technological advances prompting attempts to make fully complete contracts a reality,86See Richard T. Holden & Anup Malani, Can Blockchain Solve the Hold-Up Problem in Contracts? 20–28 (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Rsch., Working Paper No. 25833, 2019), https://doi.org/10.3386/w25833 (proposing that perfect commitment in contracts can be achieved with blockchain and automated “smart” contracts). solving commitment problems once and for all is not realistic. Mandatory embedded options, such as the option to waive specific provisions, are based on fundamental principles of contract law that underpin centuries of jurisprudence.87See Jolls, supra note 7, at 204. Moreover, some flexibility in enforcing contracts is often desirable, despite the risks it introduces. Parties in some cases prefer to see how circumstances external to the contract evolve before committing to a course of action.88See Bernheim & Whinston, supra note 73, at 903–04. To understand whether incomplete contracts create significant welfare loss, lawmakers and scholars must assess the extent to which parties use their discretion to modify contract outcomes and the reasons behind it.

Information about contract performance is hard to find, however, because courts are generally unwilling or unable to scrutinize these actions.89See infra Section IV.A. A large literature has studied the effect of discretionary action in generating disparate outcomes in other contexts, including administrative law and criminal justice.90See supra note 58. Affording discretion to contracting parties is different from those contexts because individuals can opt out of contracts but not out of the criminal justice system or the administrative state. But although unequal treatment within a contract may not raise concerns about coercion, it still raises concerns about economic efficiency. Despite this, inequality is classified as “relational,” meaning that parties’ discretionary choices are outside the purview of courts and regulators.91See Benjamin E. Hermalin, Avery W. Katz & Richard Craswell, Contract Law, in 1 Handbook of Law and Economics 3, 19 (A. Mitchell Polinsky & Steven Shavell eds., 2007); Charles J. Goetz & Robert E. Scott, Principles of Relational Contracts, 67 Va. L. Rev. 1089, 1091 (1981); Bernstein & Volvovsky, supra note 3, at 129–30.

The common law of contracts also prevents parties from agreeing to limit contract incompleteness. Mandatory embedded contract options, such as breach and modification, cause inefficiencies because no party can commit fully to not breaching or not renegotiating a contract.92See Jolls, supra note7, at 204. Waiver and the exercise of discretion are difficult to contract around as well, although some doctrines exist to discipline their usage.93The duty of good faith applies to these contract levers. See infra Section IV.A.1. These legal levers are discussed in turn below.

II. How Contract Law Creates Unequal Outcomes

The common law of contract has long enabled contractual inequality.94Scott & Triantis, Embedded Options, supra note 12, at 1447–52. Consider a typical debtor-creditor relationship in which the debtor is facing financial pressure. What choices does a debtor have when faced with the possibility that future payments will be difficult to make? The debtor could decide to prepay in anticipation of financial distress or offer partial payment after distress occurs in an exercise of discretion. The debtor could also breach and make no payment at all. Second, what choices does a creditor have if faced with the possibility that the debtor may be unable to make payments? The creditor could preemptively offer the debtor a modification of the debt obligations to make it easier for the debtor to make payments. The creditor could also waive the debtor’s obligation to pay on time, providing a forbearance period to accommodate the debtor’s needs while preserving their rights to collect on the original agreement.

More broadly, the exercise of reserved discretion, waiver of obligations, and the decision to breach, modify, enforce, or renegotiate a contract can each be utilized to generate unequal outcomes from standard form contracts. Empirical studies in economics, finance, and accounting have shown that contractual inequality is widespread in the context of health-insurance contracts, commercial debt, and household borrowing.95E.g., Aviva Aron-Dine, Liran Einav, Amy Finkelstein & Mark Cullen, Moral Hazard in Health Insurance: Do Dynamic Incentives Matter?, 97 Rev. Econ. & Stat. 725 (2015) (demonstrating that consumers of health insurance strategically utilize health care depending on the structure of the health-insurance plan, while satisfying the formal requirements of the contract terms); Kristopher Gerardi, Kyle F. Herkenhoff, Lee E. Ohanian & Paul S. Willen, Can’t Pay or Won’t Pay? Unemployment, Negative Equity, and Strategic Default, 31 Rev. Fin. Stud. 1098 (2018) (finding that decisions to default on or breach mortgage contracts depend on private experiences of job loss and the value of housing assets, with approximately a third of defaults being classified as “strategic” or discretionary); Kevin C.W. Chen & K.C. John Wei, Creditors’ Decisions to Waive Violations of Accounting-Based Debt Covenants, 68 Acct. Rev. 218 (1993) (providing evidence that financial covenants attached to commercial debt agreements are strategically waived, to the benefit of firms with higher chances of future success); Michael R. Roberts, The Role of Dynamic Renegotiation and Asymmetric Information in Financial Contracting, 116 J. Fin. Econ. 61 (2015) (showing that the average corporate bank loan is renegotiated every nine months to account for new information). This Part uses examples from this literature to demonstrate the principles of contract law generating performance inequality and their widespread impacts.

A. Exercise of Discretion

A party exercises its discretion when a range of options would satisfy the requirements of a formal contract and the party can unilaterally choose among these options. One form of exercising discretion arises when a party has explicitly reserved the right to make a discretionary choice within the formal contract terms, such as the choice of production amount in an output contract or the choice to exert efforts in an exclusive dealing contract, or more generally the type of choice governed by a mandatory common law duty of good faith.96The Restatement (Second) of Contracts states that “[e]very contract imposes upon each party a duty of good faith and fair dealing in its performance and its enforcement.” Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 205 (Am. Law Inst. 1981). Likewise, the Uniform Commercial Code “imposes an obligation of good faith in [every contract’s] performance and enforcement.” U.C.C. § 1-304 (Am. L. Inst. & Unif. L. Comm’n 2019). Discretion also exists in the utilization of well-defined formal obligations, such as the choice to enforce a right, as will be discussed below.

A well-studied example of the exercise of discretion arises in the context of health-insurance contracts. Consumers of health care purchase insurance plans to smooth their potential expenditures over the contract term. A plan typically specifies the amount of coverage, comprising a deductible that is paid out of pocket and partial or complete coverage of expenditures above the deductible amount. Economists have documented that consumers obtain health care in a way that minimizes their out-of-pocket expenditures.97See Aron-Dine et al., supra note 95, at 725, 737; Liran Einav & Amy Finkelstein, Moral Hazard in Health Insurance: What We Know and How We Know It, 16 J. Eur. Econ. Ass’n 957, 958–60 (2018). For instance, it is cheaper to visit the doctor for a checkup at the end of the year, when the deductible has already been spent and insurance covers additional care, than waiting until the following January to get a checkup that will require out-of-pocket-payment. It would be entirely within the bounds of the formal contract to strategically reschedule doctor’s visits to the end of the year. If sophisticated consumers decide to get more specialist care in years when their spending is already high, the insurance company bears the cost and no contract term can be used to deny the claim. This generates inequality among insurance companies. Companies whose sophisticated consumers strategically reschedule their health care consumption will have to pay out more, while companies with unsophisticated consumers will pay out less.98Indeed, insurance companies anticipate this behavior and attempt to find customers without strategic consumption patterns. Liran Einav et al., Selection on Moral Hazard in Health Insurance, 103 Am. Econ. Rev. 178 (2013).

Note that the inequality in this example arises directly from the incompleteness of the insurance contract. Insurance companies could require their customers to provide documentation that doctor’s visits were scheduled in a timely fashion or could ration discretionary medical care to limit strategic consumption. Instead, insurance companies have taken another tactic for limiting the cost of inequality—they set premiums to compensate for the possibility of strategic health care consumption.99See id. at 214–15. Parties bargain for and assent to agreements that leave discretion in their hands, explicitly allowing for unequal outcomes to arise.

B. Breach of Contract

Parties to a contract can always choose to breach their obligations to their counterparty. The option to breach is embedded in every contract and comes with the implicit cost of damages or other restitution from the harmed party.100Since Holmes, breach has been thought of as a valid, if not ideal, choice to be made by parties to the contract. See O.W. Holmes, The Path of the Law, 10 Harv. L. Rev. 457, 462 (1897) (“The duty to keep a contract at common law means a prediction that you must pay damages if you do not keep it,—and nothing else.”). Recent scholarship in law and economics has sought to separate the moral requirements of contracts from the economic requirements, holding breach to be potentially efficient. For a history and an attempt at reconciliation of the economic and moral views of breach, see Richard R.W. Brooks, Essay, The Efficient Performance Hypothesis, 116 Yale L.J. 568 (2006). Breach-of-contract claims require no showing of fault and therefore impose strict liability on a breaching party.101For a review of the history of strict liability for breach of contract, as distinguished from fault regimes in tort, see Robert E. Scott, In (Partial) Defense of Strict Liability in Contract, 107 Mich. L. Rev. 1381 (2009). This can be thought of as putting a “price” on breach. When two sets of parties are engaged in similar contracts, the strategic choice by one party to breach while its analogue continues to perform generates contractual inequality.

The strategic choice to breach has been studied by economists and lawmakers in the context of mortgage default. The decision to stop making payments on a mortgage constitutes breach—the terms of all mortgage contracts require mortgagees to make timely payments.102See Gerardi et al., supra note 95. Occasionally, default is unavoidable, with the mortgagee facing a liquidity crisis that makes payment impossible. On the other hand, some may decide to breach despite being able to perform if necessary. This is referred to as strategic default.103Tess Wilkinson-Ryan, Breaching the Mortgage Contract: The Behavioral Economics of Strategic Default, 64 Vand. L. Rev. 1547 (2011) (summarizing the literature on strategic default and concluding that changing social norms encourage strategic mortgagee decisionmaking). Mortgagees would rationally prefer to default if the value of their home drops so low that they no longer have any equity interest in the home, that is, if the mortgage is underwater. In this case, further payments toward a principal amount that is too high would be wasted. Moreover, failing to pay would force the creditor or servicer to choose whether to foreclose on the property. If the loan is underwater, foreclosure may not make the creditor whole. By strategically defaulting, a mortgagee may benefit by remaining in the house without payment until the home’s value increases. On the other hand, strategic defaults are considered both morally dubious and potentially harmful to the value of neighboring properties and communities.104Michael G. Bradley, Amy Crews Cutts & Wei Liu, Strategic Mortgage Default: The Effect of Neighborhood Factors, 43 Real Est. Econ. 271, 273 (2015) (finding that strategic default is “contagious” in neighborhoods, leading to higher aggregate financial risks); Luigi Guiso, Paola Sapienza & Luigi Zingales, The Determinants of Attitudes Toward Strategic Default on Mortgages, 68 J. Fin. 1473, 1498–1502 (2013) (showing that homeowners prefer not to default on underwater mortgages when they believe they have a moral obligation to perform on their contract); Michael J. Seiler, Understanding the Far-Reaching Societal Impact of Strategic Mortgage Default, 22 J. Real Est. Literature 205 (2014) (noting the spillover effects of strategic default on the financial sector, neighborhood welfare, and other economic sectors).