Administrative Sabotage

Government can sabotage itself. From the president’s choice of agency heads to agency budgets, regulations, and litigating positions, presidents and their appointees have undermined the very programs they administer. But why would an agency try to put itself out of business? And how can agencies that are subject to an array of political and legal checks sabotage statutory programs?

This Article offers an account of the “what, why, and how” of administrative sabotage that answers those questions. It contends that sabotage reflects a distinct mode of agency action that is more permanent, more destructive, and more democratically illegitimate than more-studied forms of maladministration. In contrast to an agency that shirks its statutory duties or drifts away from Congress’s policy goals, one engaged in sabotage aims deliberately to kill or nullify a program it administers. Agencies sabotage because presidents ask them to. Facing pressure to dismantle statutory programs in an environment where securing legislation from Congress is difficult and politically costly, presidents pursue retrenchment through the administrative state.

Building on this positive theory of administrative sabotage, this Article considers legal responses. The best response, this Article contends, is not reforms to the cross-cutting body of administrative law that structures most agency action. Rather, the risk of sabotage is better managed through changes to how statutory programs are designed. Congress’s choices about agency leadership, the concentration or dispersal of authority to implement statutory programs, the breadth of statutory delegations, and other matters influence the likelihood that sabotage will succeed or fail. When lawmakers create or modify federal programs, they should design them to be less vulnerable to sabotage by the very agencies that administer them.

Introduction

In 2010, Congress enacted the Dodd-Frank Act in an effort to address the market failures that triggered the 2008 financial crisis.1Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010) [hereinafter Dodd-Frank Act] (codified as amended in scattered sections of the United States Code). Following the recommendations of an article coauthored by then-Professor Elizabeth Warren,2Oren Bar-Gill & Elizabeth Warren, Making Credit Safer, 157 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1 (2008). the Act sought to regulate “unsafe” financial products that Congress believed imposed a variety of negative externalities on society.3See. e.g., Dodd-Frank Act §§ 501–533 (regulating insurance markets); id. §§ 601–628 (regulating depository institutions); id. §§ 1400–1498 (regulating mortgages). Title X of Dodd-Frank, known as the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010, created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and charged it with enforcing eighteen consumer financial laws.4Id. § 1011 (establishing CFPB); id. §§ 1021(a), (c) (authorizing CFPB to enforce federal consumer financial laws); id. § 1022(12) (enumerating consumer financial laws the Bureau administers).

In its early years under Director Richard Cordray, the CFPB pursued its statutory mission with zeal. The Bureau aggressively investigated predatory lenders, mortgage companies, and credit-card companies.5See Christopher L. Peterson, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Law Enforcement: An Empirical Review, 90 Tul. L. Rev. 1057, 1076–77 (2016). Information from supervision and enforcement drove rulemaking in areas such as payday lending6See Press Release, CFPB, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Proposes Rule to End Payday Debt Traps (June 2, 2016), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/CFPB_Proposes_Rule_End_Payday_Debt_Traps.pdf [perma.cc/9W9S-DFQW]. and debt collection.7See Richard Cordray, Dir., CFPB, Remarks at the Consumer Advisory Board Meeting (June 8, 2017), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/prepared-remarks-cfpb-director-richard-cordray-consumer-advisory-board-meeting-june-2017 [perma.cc/JS23-XE88]. Within five years, the Bureau was returning an average of $43 million per week from financial services companies to consumers.8Christopher L. Peterson, Consumer Fed’n of Am., Dormant: The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Law Enforcement Program in Decline 15 tbl.1 (2019), https://consumerfed.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CFPB-Enforcement-in-Decline.pdf [perma.cc/96CA-YD26].

But in December 2017, Cordray resigned to run for governor of Ohio,9Sylvan Lane, Former Consumer Bureau Director Cordray Announces Run for Ohio Governor, Hill (Dec. 5, 2017, 1:44 PM), https://thehill.com/policy/finance/363344-former-consumer-bureau-director-cordray-announces-run-for-ohio-governor [perma.cc/L9HA-23M4]. and President Trump used the Federal Vacancies Reform Act105 U.S.C. §§ 3345–3349d. to replace him with Mick Mulvaney, the director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).11See Renae Merle, The CFPB Now Has Two Acting Directors. And Nobody Knows Which One Should Lead the Federal Agency, Wash. Post (Nov. 24, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2017/11/24/the-cfpb-now-has-two-acting-directors-and-nobody-knows-which-one-should-lead-the-federal-agency [perma.cc/EXH8-VNEU]. In one of the stranger episodes of the Trump administration, Cordray appointed Leandra English as the CFPB’s deputy director before he left office; she and Mulvaney both claimed the right to lead the agency. A district court rejected English’s motion for a preliminary injunction recognizing her right to lead the agency, and English abandoned the case before it proceeded further. English v. Trump, 279 F. Supp. 3d 307 (D.D.C. 2018); see also Sylvan Lane, Biden Consumer Bureau Pick Could Take Over Agency on Inauguration Day, Hill (Jan. 19, 2021, 4:47 PM), https://thehill.com/policy/finance/534884-biden-consumer-bureau-pick-could-take-over-agency-on-inauguration-day [perma.cc/YW9L-GWGZ]. A long-time ally of the payday lending industry,12See George Zornick, Why Loan Sharks, Car Salesmen, and Payday Lenders Love Mick Mulvaney, Nation (Sept. 13, 2018), https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/why-loan-sharks-car-salesmen-and-payday-lenders-love-mick-mulvaney [perma.cc/UAJ4-BK7Z]. Mulvaney once sponsored legislation to abolish the CFPB and stated at a House hearing that he didn’t “like the fact that CFPB exists.”13Merle, supra note 11.

At the helm of an agency he “detest[ed],”14Devin Leonard & Elizabeth Dexheimer, Mick Mulvaney Is Having a Blast Running the Agency He Detests, Bloomberg Businessweek (May 25, 2018, 5:28 PM), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-05-25/mick-mulvaney-on-the-cfpb-we-re-still-elizabeth-warren-s-child [perma.cc/KZP5-PATF] (cleaned up). Mulvaney moved to cripple it. Mulvaney declined to request money to fund the Bureau’s operations;15Kate Berry, Mulvaney Requests ‘Zero’ Money for CFPB, Am. Banker (Jan. 18, 2018, 10:11 AM), https://www.americanbanker.com/news/mulvaney-requests-zero-money-for-cfpb [perma.cc/5DPH-J2LZ]. installed “policy associate directors”16Nicholas Confessore, Mick Mulvaney’s Master Class in Destroying a Bureaucracy from Within, N.Y. Times Mag. (Apr. 16, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/16/magazine/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-trump.html [perma.cc/3CVC-ZNAT]. to shadow Bureau chiefs protected by the civil service laws;17Kate Berry, Meet Mulvaney’s ‘Politicos’: Six Senior Staff Remaking the CFPB, Am. Banker (May 7, 2018, 5:11 PM), https://www.americanbanker.com/news/meet-mick-mulvaneys-politicos-six-senior-staff-remaking-the-cfpb [perma.cc/F7UP-C97L]. rescinded, stayed, or delayed major rules on payday lending, overdraft fees, and student loan servicing;18See Ganesh Sitaraman, The Supreme Court, 2019 Term—Comment: The Political Economy of the Removal Power, 134 Harv. L. Rev. 352, 372 (2020). and lent the Bureau’s support to a constitutional challenge to the Bureau’s structure, in which the petitioner asked the Supreme Court to “invalidate Title X.”19See CFPB, Semi-annual Report of the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection 1–2 (2018), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_semi-annual-report_spring-2018.pdf [perma.cc/6R33-CDNS]; Reply Brief for the Petitioner at 19, Seila L. LLC v. CFPB, 140 S. Ct. 2183 (2020) (No. 19-7). According to one commentator, these actions left the CFPB in a “vegetative state.”20Sitaraman, supra note 18, at 373 (quoting Bess Levin, Mick Mulvaney Won’t Rest Until He’s Exorcised Elizabeth Warren from the C.F.P.B., Vanity Fair (May 25, 2018), https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2018/05/mick-mulvaney-elizabeth-warren-exorcism [perma.cc/U4XR-8F92]).

Mulvaney’s attack on the CFPB and the Bureau’s attack on Title X under him highlight an important gap in our understanding of the U.S. administrative state. From the Affordable Care Act to laws protecting consumers, financial markets, and the environment, major statutory programs are administered by executive departments and administrative agencies.21In federal statutory law, executive agencies, executive departments, and independent regulatory commissions are distinct kinds of entities. The differences among these kinds of institutions are for the most part unimportant to my goals in this Article. Thus, I use “agencies” as a shorthand to refer to all three. I use “statutory program” to refer to legislation that is administered, in whole or part, by an agency or executive department. Scholars have long appreciated that Congress’s delegation of authority to agencies creates risks of slacking, drift, and capture: agencies might perform their functions lethargically,22See, e.g., Sean Farhang, The Litigation State: Public Regulation and Private Lawsuits in the U.S. 70 (2010) (“[A]n enacting legislative coalition, mindful that the stickiness of the status quo will make legislative override of bureaucrats difficult, will want to safeguard in advance against bureaucrats deviating from the coalition’s preferences based upon bureaucrats’ own policy preferences, careerism, propensity to shirk, or acquiescence to capture.”); Matthew C. Stephenson, Public Regulation of Private Enforcement: The Case for Expanding the Role of Administrative Agencies, 91 Va. L. Rev. 93, 110 (2005) (noting that private enforcement regimes can correct “the tendency of government regulators to underenforce certain statutory requirements because of political pressure, lobbying by regulated entities, or the laziness or self-interest of the regulators themselves” (footnotes omitted)). depart from Congress’s preferences in administering a program,23See, e.g., David Epstein & Sharyn O’Halloran, Delegating Powers: A Transaction Cost Politics Approach to Policy Making Under Separate Powers 48 (1999) (“[G]iven that delegation implies surrendering at least some residual rights of control over policy, legislators will be loath to relinquish authority in politically sensitive policy areas where they cannot be assured that the executive will carry out their intent.”); Matthew D. McCubbins, Roger G. Noll & Barry R. Weingast, Structure and Process, Politics and Policy: Administrative Arrangements and the Political Control of Agencies, 75 Va. L. Rev. 431, 438–39 (1989) (“Once a policy is enacted, the agency must implement it. In so doing, the agency may shift the policy outcome away from the legislative intent . . . .”). or consistently advance the interests of a regulated industry.24See Daniel Carpenter & David A. Moss, Introduction, in Preventing Regulatory Capture: Special Interest Influence and How to Limit It 1, 13 (Daniel Carpenter & David A. Moss eds., 2014) (“Regulatory capture is the process by which regulation, in law or application, is consistently or repeatedly directed away from the public interest and toward the interests of the regulated industry, by the intent and action of the industry itself.” (emphasis omitted)). But with a handful of recent exceptions,25See, e.g., Abbe R. Gluck & Thomas Scott-Railton, Affordable Care Act Entrenchment, 108 Geo. L.J. 495, 548 (2020); Madeline June Kass, Presidentially Appointed Environmental Agency Saboteurs, 87 UMKC L. Rev. 697 (2019); Patricia A. McCoy, Inside Job: The Assault on the Structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 103 Minn. L. Rev. 2543 (2019). Two recent works offer broader perspectives on issues related to administrative sabotage. In a cross-national study, Michael Bauer and Stefan Becker identify sabotage as one of four strategies that populists who are elected to office use to “transform public administration according to their anti-pluralist ideology.” Michael W. Bauer & Stefan Becker, Democratic Backsliding, Populism, and Public Administration, 3 Persps. on Pub. Mgmt. & Governance 19 (2020). Focusing on the Trump administration, Jody Freeman and Sharon Jacobs examine structural deregulation, a set of strategies that track what this Article terms “systemic” sabotage. Jody Freeman & Sharon Jacobs, Structural Deregulation, 135 Harv. L. Rev. 585 (2021). scholars have not focused on the possibility that agencies might affirmatively attack programs they administer—a phenomenon this Article terms “administrative sabotage.”

Administrative sabotage raises thorny questions. An influential strand of public choice scholarship views agencies as “budget maximizers” that continuously undersupply policy outcomes desired by Congress while maximizing their own budgets.26The classic work is William A. Niskanen, Jr., Bureaucracy and Representative Government (1971). Why, contrary to this image, would an agency aim to put itself out of business? Is sabotage different than agency slacking and drift or merely an extreme form of those phenomena? Given the political and legal checks on agencies, how can they successfully sabotage a statutory program?

This Article offers a theoretical and legal account of administrative sabotage that answers those questions. The core claim is that presidents use agencies to pursue statutory retrenchment that is costly, if not impossible, to obtain directly from Congress. This affects our understanding of what agencies are. Agencies not only enforce, elaborate, and implement statutory policy but can undermine and dismantle the programs they administer.

I begin by making the case that administrative sabotage reflects a distinct mode of agency action. Part I offers additional examples of administrative sabotage, distinguishes sabotage from other kinds of maladministration, and explains why sabotage is normatively objectionable.

Part I also explains that sabotage exists in something of a legal grey area. The use of agency power to attack statutory programs encroaches on Congress’s legislative authority, is in tension with the executive’s constitutional duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,”27U.S. Const. art. II, § 3. and violates statutory provisions that contemplate good-faith policy implementation. But concerns about intruding on a coordinate branch of government frequently prevent courts from effectively checking administrative sabotage.

Having defined administrative sabotage, Part II turns to its origins. Administrative sabotage is a tool for retrenching federal statutory programs. Demand for it originates in larger political and ideological opposition to an activist federal government. Yet sabotage would not occur were it not for other long-term trends in U.S. law and politics.

Those trends weaken presidents’ ability to secure new legislation while strengthening their power over programs that have already been enacted into law. On one hand, the complexity of the legislative process and the distinctive politics of statutory retrenchment make it difficult for presidents to secure legislation rolling back enacted programs. On the other hand, Congress has delegated significant authority to agencies, presidents have expanded the White House’s ability to control agencies through “presidential administration,” congressional oversight has been weakened by the emergence of polarized political parties, and courts are increasingly open to reconfiguring or dismantling statutory programs based on creative legal arguments.

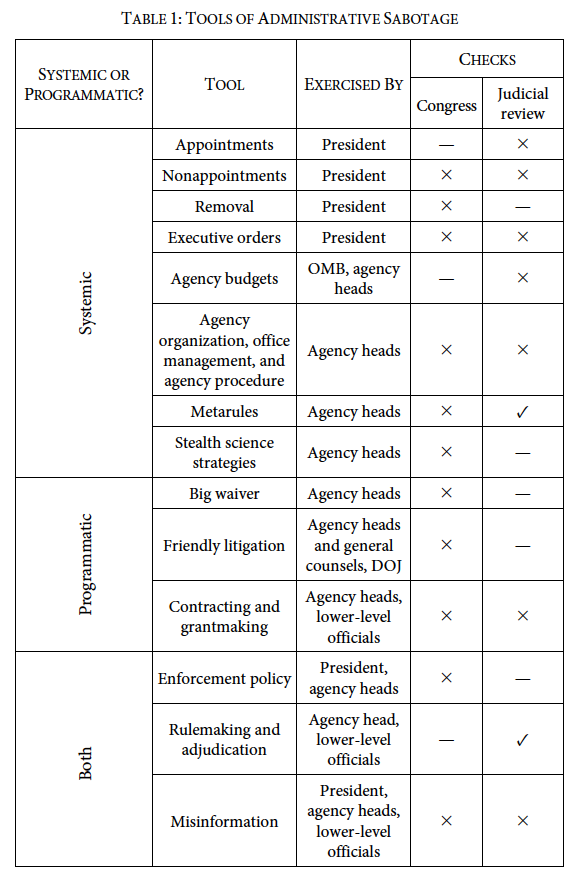

Constrained on the one hand and empowered on the other, presidents pursue statutory retrenchment that Congress will not give them through the administrative state. In Part III, I catalogue the tools available to a motivated administration for sabotaging statutory programs and analyze the likelihood that the tools will be checked by Congress or the courts. Overall, checks on administrative sabotage are inconsistent, and their effectiveness depends on contingent historical conditions such as partisan control of Congress. Sabotage, then, is not just a distinct mode of agency action but likely represents a new normal.28Accord Nicholas Bagley, Executive Power and the ACA, in The Trillion Dollar Revolution: How the Affordable Care Act Transformed Politics, Law, and Health Care in America 192, 198 (Ezekiel J. Emanuel & Abbe R. Gluck eds., 2020); cf. James A. Morone, Partisanship, Dysfunction, and Racial Fears: The New Normal in Health Care Policy?, 41 J. Health Pol. Pol’y & L. 827 (2016). Particularly during conservative administrations, agencies are likely to use their delegated authority to attack disfavored programs.

Administrative sabotage complicates traditional accounts of the bureaucracy. After briefly highlighting these theoretical implications, Part IV considers legal responses. Although existing checks on sabotage are weak, changes to procedural requirements, statutory and institutional design, and the law of judicial review could potentially counteract it. A crucial question about such reforms is whether sabotage is best addressed through cross-cutting reforms that apply to agencies in general or through changes to specific agencies and programs.

I argue that cross-cutting reforms are a poor response to the risk of sabotage. Subjecting agencies to new procedural and analytical requirements and expanding the scope of judicial review would make sabotage more difficult at the margin, but these reforms would also impede legitimate efforts to implement statutory policy. Instead, I argue that the risk of sabotage is better addressed through statutory and institutional design. A host of choices affect statutory programs’ resilience against sabotage. While the risk of sabotage cannot be eliminated, it complicates and in some cases reorients long-running debates about the design of statutory programs.

I. Fundamentals

Consider the following executive actions:

- The president appoints an EPA administrator who opposed federal environmental regulation as a state lawmaker. In her first speech to the agency, she announces, “We’re going to do more with less and we’re going to do it with fewer of you.”

Each of these cases involves actions that are the ordinary stuff of the administrative process: appointments, office reorganizations, budgeting, rulemaking, and public communications. But the actions also differ from the textbook image of agency administration, insofar as they seem designed to undermine programs that the executive is charged with administering. This tension raises the question whether it is coherent—and useful—to view administrative sabotage as a distinctive mode of agency action.

This Part makes the case that it is. Administrative sabotage is defined by intent: an agency aims to kill or nullify a statutory program. Section I.A develops this definition. Section I.B considers sabotage’s relationship to agency slacking, drift, and capture. Section I.C explores why administrative sabotage is normatively objectionable and rebuts the argument that the president’s popular mandate makes sabotage democratically legitimate. Finally, Section I.D explores the reasons that courts, for the most part, do not directly police sabotage.

A. Defining Administrative Sabotage

An agency can sabotage many things: economic conditions, a presidential administration, a business or industry. This Article focuses on the sabotage of statutory programs by agencies that administer them.

In defining administrative sabotage, I draw on work in law and public administration on related forms of sabotage. John Brehm and Scott Gates study bureaucrats in state and federal bureaucracies and classify their actions as “working, shirking, and sabotage.”29John Brehm & Scott Gates, Working, Shirking, and Sabotage: Bureaucratic Response to a Democratic Public 21 (1997) (cleaned up). They define sabotage as bureaucratic action that “deliberately undermin[es] the policy objectives of their superiors.”30Id. at 21. Marissa Martina Golden studies executive agencies’ responsiveness to the president’s policy agenda and approaches “sabotage” as bureaucratic action that undermines the president.31See Marissa Martino Golden, What Motivates Bureaucrats? Politics and Administration During the Reagan Years 17 (2000) (finding little evidence that bureaucratic sabotage occurred during the Reagan administration). In a formal model of legislative delegation to an imperfectly controlled, expert bureaucrat, Sean Gailmard defines “subversion” as any action outside the discretionary policy bounds set by the legislature.32Sean Gailmard, Expertise, Subversion, and Bureaucratic Discretion, 18 J.L. Econ. & Org. 536, 537 (2002).

The first point suggested by this literature is that administrative sabotage takes place within a principal-agent relationship.33See Brehm & Gates, supra note 42, at 25. The principal in this relationship is Congress. The agent is the administrative agency that administers the program.34This view of agencies follows from the black-letter definition of an agency: “[A]n agency literally has no power to act . . . unless and until Congress confers power upon it.” La. Pub. Serv. Comm’n v. FCC, 476 U.S. 355, 374 (1986). It also comports with the standard view of agencies in positive political theory. See Sean Gailmard & John W. Patty, Formal Models of Bureaucracy, 15 Ann. Rev. Pol. Sci. 353 (2012). It bears noting, however, that agencies are subject to some degree of control by the president, the boundaries of which are deeply contested. See Peter L. Strauss, Foreword, Overseer, or “The Decider”? The President in Administrative Law, 75 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 696 (2007).

Second, administrative sabotage involves a specific stance on the part of the agency toward the program it administers. The agency does not over- or underenforce a policy relative to a hypothesized baseline,35See Gailmard & Patty, supra note 47, at 365–66. or shift statutory policy within the “space” a statute creates,36See Peter L. Strauss, Essay, “Deference” Is Too Confusing—Let’s Call Them “Chevron Space” and “Skidmore Weight,” 112 Colum. L. Rev. 1143, 1146–47 (2012) (explaining that when Chevron deference applies to an agency’s statutory interpretation, “Congress has created the agency’s freedom to act within its space anticipating presidential oversight”). but seeks to eliminate a program it administers. Identifying sabotage thus requires analysis of agency decisionmakers’ intent. The intent to kill or nullify a statutory program distinguishes sabotage as a mode of agency action.37Cf. Freeman & Jacobs, supra note 25, at 627 (“The real question is whether . . . agency reforms that have potential to reduce functional capacity appear to have been taken in good faith with a legitimate purpose other than weakening the agency’s ability to perform its legislative tasks.”); Randy E. Barnett, The President’s Duty of Good Faith Performance, Reason: Volokh Conspiracy (Jan. 12, 2015), https://reason.com/volokh/2015/01/12/the-presidents-duty-of-good-fa-2 [perma.cc/DJE9-8XVP] (arguing that determining whether an enforcement policy complies with the Take Care Clause requires analysis of whether nonenforcement is motivated by disagreement with the law not being enforced).

Third, administrative sabotage can target an entire statutory program, such as the ACA, or a discrete aspect of a program, such as the ACA’s minimum essential coverage provisions. Every presidential administration likely engages in some small-bore forms of sabotage. As the scope of sabotage expands, however, so do the normative concerns it raises. More on those concerns in a moment.

Fourth, administrative sabotage can succeed, fail, or produce a range of outcomes in between. Given the stickiness of enacted law, it is not surprising that many attempts at sabotage fail. But the line between successful and unsuccessful sabotage is uncomfortably thin. Consider the Trump Justice Department’s support for Texas v. United States, the most recent constitutional challenge to the ACA.38See infra notes 113–118 and accompanying text. There, a stay pending appeal was all that prevented a district court from invalidating the Act in its entirety.39Texas v. United States, 352 F. Supp. 3d 665, 690 (N.D. Tex. 2018), aff’d in part, 945 F.3d 355 (5th Cir. 2020), rev’d sub nom. California v. Texas, 141 S. Ct. 2104 (2021).

Based on the foregoing, this Article defines administrative sabotage as follows: an agency engages in administrative sabotage when it deliberately seeks to kill or nullify a statutory program, in whole or part, that Congress has charged the agency with administering.40I use “kill” to refer to agency action that deprives a statutory program of the force of law and “nullify” to refer to action that leaves a program in place but deprives it of any practical effect.

B. Sabotage, Slacking, Drift, and Capture

Administrative sabotage is related to, but different from, other forms of agency action that scholars have explored at length. We can sharpen our understanding of sabotage by comparing it to these phenomena.

First, administrative sabotage is not the same as the undersupply of policy outcomes Congress desires, variously known as slacking,41E.g., Stephenson, supra note 22, at 110. shirking,42E.g., Mathew D. McCubbins, Roger G. Noll & Barry R. Weingast, Administrative Procedures as Instruments of Political Control, 3 J.L. Econ. & Org. 243, 247 (1987). or nonenforcement.43See, e.g., Daniel T. Deacon, Note, Deregulation Through Nonenforcement, 85 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 795 (2010). For example, Congress might direct the Internal Revenue Service to audit ten thousand high-income taxpayers per year and provide the requisite authority and appropriations.44Cf. H.R. 1200, 117th Cong. § 3(a) (2021) (directing IRS to audit 50 percent of individual tax returns with an income over million a year). If the agency simply refuses to conduct the audits, it is slacking. If it refuses to perform the audits and fires all of its personnel who are capable of performing the audits, it is engaged in slacking and sabotage.

As this suggests, what distinguishes sabotage from mere slacking is the agency’s intent to kill or nullify the program. The agency does not simply take its foot off the pedal but totals the vehicle, making it impossible for later agency heads to restart. Where sabotage succeeds, its effects are more lasting than mere slacking.45Analyzing the impact of Secretary Purdue’s office moves at the Department of Agriculture, see supra text accompanying note 35, the House Appropriations Committee concluded that the two affected offices “are shells of their former selves” and that “the loss of institutional knowledge each agency has suffered will take years to overcome.” Ryan McCrimmon, Farm Spending Bill Set for House Markup, POLITICO (July 9, 2020, 10:00 AM), https://www.politico.com/newsletters/morning-agriculture/2020/07/09/farm-spending-bill-set-for-house-markup-789049 [perma.cc/G3WP-MP4J], quoted in Skowronek et al., supra note 33, at 116. Seen in terms of the agency’s fealty to its statutory mandate, this is an important difference of kind. The agency does not simply fail to enforce but uses nonenforcement as a means of eliminating or disabling the sabotaged program.

Sabotage also differs from agency “drift,” or the “risk that implemented policy will differ from what the enacting legislative coalition would prefer.”46Jacob E. Gersen, Designing Agencies, in Research Handbook on Public Choice and Public Law 333, 338 (Daniel A. Farber & Anne Joseph O’Connell eds., 2010). If we model statutory policy along a simple liberal-to-conservative spectrum, a conservative agency might implement a liberal statute more conservatively than the enacting Congress expected, and vice versa.

Most analyses of agency drift assume that it occurs within the space created by the statute.47See, e.g., id. at 337; J.R. DeShazo & Jody Freeman, The Congressional Competition to Control Delegated Power, 81 Tex. L. Rev. 1443, 1445 (2003); McCubbins et al., supra note 23, at 438–39. For example, the Federal Trade Commission might adopt an understanding of anticompetitive conduct that is more or less restrictive than Congress contemplated.48See John J. Flynn, The Reagan Administration’s Antitrust Policy, “Original Intent” and the Legislative History of the Sherman Act, 33 Antitrust Bull. 259 (1988). Sabotage is different. The agency does not implement a statute in a manner that departs from Congress’s preferences but aims to kill the program itself.

Finally, administrative sabotage is different than agency or regulatory capture, the “process by which regulation, in law or application, is consistently or repeatedly directed away from the public interest and toward the interests of the regulated industry, by the intent and action of the industry itself.”49Carpenter & Moss, supra note 24. As this definition suggests, capture is a process through which public authority is used for private ends. A regulated industry might capture an agency and direct it to engage in sabotage. But the industry might also have the agency protect it from regulation, protect it from competition, or even overregulate.50See Sidney A. Shapiro, The Complexity of Regulatory Capture: Diagnosis, Causality, and Remediation, 17 Roger Williams U. L. Rev. 221, 223–25 (2012). Conceptually, then, whether an agency has been captured is distinct from whether the agency is engaged in sabotage.

C. Normative Objections to Administrative Sabotage

The basic objection to administrative sabotage is that it is incompatible with democratic government under the Constitution. Even fervent critics of the administrative state acknowledge Congress’s authority to define national policy through law, create executive departments and agencies, and charge them with enforcing and elaborating statutory policies.51See Free Enter. Fund v. Pub. Co. Acct. Oversight Bd., 561 U.S. 477, 499 (2010) (“No one doubts Congress’s power to create a vast and varied federal bureaucracy.”).

Administrative sabotage subverts that model. Rather than use delegated authority to enforce and elaborate statutory policy, an agency engaged in sabotage uses that authority to undermine the program it administers. In structural constitutional terms, this use of delegated authority is at odds with the principle of legislative supremacy.52See Kendall v. United States ex rel. Stokes, 37 U.S. (12 Pet.) 524, 613 (1838) (rejecting argument that the Take Care Clause empowers the president to disregard enacted law on the grounds that such a power would “cloth[e] the President with a power entirely to control the legislation of congress, and paralyze the administration of justice”). To the extent that it is done with the president’s blessing, sabotage also breaches the executive’s duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”53U.S. Const. art. II, § 3. Although many aspects of the Take Care Clause’s meaning are unresolved,54Jack Goldsmith & John F. Manning, The Protean Take Care Clause, 164 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1835 (2016). virtually everyone agrees that it requires good-faith execution of duly enacted laws.55See id. at 1858; Andrew Kent, Ethan J. Leib & Jed Handelsman Shugerman, Faithful Execution and Article II, 132 Harv. L. Rev. 2111, 2118 (2019); Josh Blackman, The Constitutionality of DAPA Part II: Faithfully Executing the Law, 19 Tex. Rev. L. & Pol. 213, 219 (2015); Zachary S. Price, Enforcement Discretion and Executive Duty, 67 Vand. L. Rev. 671, 698 (2014). Administrative sabotage is bad-faith, not good-faith, administration.56As David Pozen has explored, the notion of bad faith is used to describe many kinds of objectionable conduct in constitutional law and politics. Administrative sabotage involves a “classic” form of bad faith: “the use of deception to conceal or obscure a material fact, a malicious purpose, or an improper motive or belief, including the belief that one’s own conduct is unlawful.” David E. Pozen, Constitutional Bad Faith, 129 Harv. L. Rev. 885, 892 (2016).

The maladministration of the laws inherent to sabotage affects the beneficiaries of sabotaged programs. Programs protecting health, the environment, and markets seek to overcome collective action problems to address pressing social challenges. When those programs are sabotaged, their ability to provide the goods that lawmakers enacted them to provide is compromised.

But there is more to dislike about sabotage. The programs that sabotage undermines are enacted through a legislative process that is designed to accommodate competing interests and provide opponents of those programs the opportunity to voice their objections. Scholars have advanced powerful arguments that Congress’s design entrenches minority rule, hampers responses to urgent collective action problems, and perpetuates white supremacy.57See, e.g., Adam Jentleson, Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy (2021); Sanford Levinson, Our Undemocratic Constitution (2006); Robert A. Dahl, How Democratic Is the American Constitution? (2d ed. 2003). Yet for all of Congress’s flaws, enacted legislation has a strong claim to democratic legitimacy. Enacted laws must navigate an obstacle course of veto points and draw support from a wide range of representatives and senators.58See infra text accompanying note 150. Presidents are subject to none of these constraints. Insofar as sabotage privileges the president’s views about the desirability of maintaining statutory programs over congressional judgments expressed in law, sabotage is undemocratic.

Defending their attacks on the statutory programs they administer, agency heads have argued that the president’s popular mandate legitimates administrative sabotage.59For example, in remarks to a bank association, Mulvaney boasted that the CFPB was “a different bureau” under him than under his predecessor Richard Cordray. That was simply “the nature of the business” because “elections do have consequences.” Steve Cocheo, “Elections Have Consequences,” Mulvaney Tells Bankers, Banking Exch. (Apr. 25, 2018, 6:58 PM), https://www.bankingexchange.com/cfpb/item/7521-elections-have-consequences-mulvaney-tells-bankers [perma.cc/AC7F-BNA2]. In doing so, they draw on a body of doctrine and scholarship that celebrates presidential control of agency action.60See, e.g., Elena Kagan, Presidential Administration, 114 Harv. L. Rev. 2245 (2001); Steven G. Calabresi, Some Normative Arguments for the Unitary Executive, 48 Ark. L. Rev. 23 (1995); Lawrence Lessig & Cass R. Sunstein, The President and the Administration, 94 Colum. L. Rev. 1, 105–06 (1994). This strand of legal scholarship elaborates on Theodore J. Lowi’s analysis of the “plebiscitary president,” which he argued had displaced the original constitutional conception of the presidency. Theodore J. Lowi, The Personal President 97–133 (1985); see also Jide Nzelibe, The Fable of the Nationalist President and the Parochial Congress, 53 UCLA L. Rev. 1217, 1226 & nn.28–33 (2006). Proponents of this “presidentialist” view argue that “because the President has a national constituency, he is likely to consider, in setting the direction of administrative policy on an ongoing basis, the preferences of the general public, rather than merely parochial interests.”61Kagan, supra note 73, at 2335. Thus, the argument goes, an agency that engages in sabotage at the president’s behest does not act undemocratically, because it merely channels the president’s views.

An initial problem with this defense of sabotage is that it misconstrues the presidentialist arguments it invokes. Presidentialists argue that presidential control of administrative agencies is necessary to maintain coherence among programs, allocate resources efficiently, and strengthen the connection between the actions of unelected bureaucrats and electoral politics.62See id. at 2331–45. Thus, presidentialists defend presidential control over agencies because it promotes the faithful execution of the laws.63See, e.g., Seila L. LLC v. CFPB, 140 S. Ct. 2183, 2191 (2020) (“[T]he Constitution gives the President ‘the authority to remove those who assist him in carrying out his duties. Without such power, the President could not be held fully accountable for discharging his own responsibilities; the buck would stop somewhere else.’” (citation omitted) (quoting Free Enter. Fund v. Pub. Co. Acct. Oversight Bd., 561 U.S. 477, 513–14 (2010))); Calabresi, supra note 73, at 58 (“It is to [the President and officers directly accountable to him] that the text of Article II of the Constitution entrusts the power of law execution, and upon them that the same text imposes the duty that the laws be ‘faithfully executed.’”). By contrast, the presidentialist defense of administrative sabotage assumes that the president’s mandate makes it democratically legitimate for him to take any action that they believe advances the national interest, no matter the lawfulness of the agency’s actions. No serious presidentialist argues this.

The more fundamental problem with the defense is its assumption that the president’s gestalt views about the continued desirability of a program are a better reflection of democratic preferences than enacted law. That assumption invokes the president’s national constituency: because the president is elected by voters nationwide, he ostensibly speaks for voters nationwide. But there are a number of problems with the idea that the president’s preferences should serve as a switch that can turn off programs enacted through regular lawmaking processes.

To begin with, when considering the extent to which they represent voters, the proper comparison is not between the president and individual members of Congress, but between the president and Congress as a whole.64Nzelibe, supra note 73, at 1249. Congress as a collective body represents practically the same number of voters as the president.65The qualifier is necessary because residents of the District of Columbia vote for president but are not fully represented in Congress. Thus, in terms of raw numbers of voters they represent, there is no reason to view the president’s views as more democratically legitimate than Congress’s.

One might think that, because the president must appeal to a national constituency to win office, the president’s views are more likely to represent the median national voter. But the idea that the president represents a national constituency is questionable. As Jide Nzelibe shows, the rules governing presidential elections allow a candidate to win with the support of as little as 25 percent of the national electorate.66Nzelibe, supra note 73, at 1234–37. This creates incentives for presidents to govern on behalf of narrow parochial interests rather than the entire nation.

Moreover, the argument that the president’s mandate legitimates sabotage ignores civic republican values that Congress is designed to foster. When an agency engages in sabotage, its actions reflect the will of a single individual whose actions are not guided by law or by predictable, rational norms. The arbitrariness of this exercise of authority is in striking contrast to the kind of deliberative, inclusive decisional process that proponents of civic republicanism celebrate.67E.g., Glen Staszewski, Political Reasons, Deliberative Democracy, and Administrative Law, 97 Iowa L. Rev. 849 (2012); Mark Seidenfeld, A Civic Republican Justification for the Bureaucratic State, 105 Harv. L. Rev. 1511 (1992).

Of course, recognizing that judgments reflected in legislation take priority over the president’s views results in a form of democratic lag. Major legislation is heavily negotiated and takes years if not decades to enact. Accordingly, legislation cannot capture popular preferences as quickly as executive action. But major programs are designed with this lag in mind and delegate authority precisely because of the difficulty of amending enacted law.68See Epstein & O’Halloran, supra note 23, at 29. Moreover, that conventional constitutional arrangements freeze Congress’s judgments in the face of changing circumstances is usually thought to be a feature, not a bug, of the constitutional scheme. Organizing social life around legislation gives individuals a voice in the norms that become law and allows them to organize their affairs around a (comparatively) stable system of legal regulation.69See Jeremy Waldron, Legislation and the Rule of Law, 1 Legisprudence 91, 107 (2007). A lag between popular preferences and enacted law is inherent in the system.

If sabotage is objectionable on constitutional, welfarist, and democratic grounds, however, this is not to say that it can never be normatively justified. Suppose, for example, that President Lincoln had used control of the executive branch to undermine the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act in the decade prior to the Civil War.70See generally Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850–1860 (1970). An intentional effort to subvert congressional regulation of slavery would have qualified as sabotage. Yet, seen through modern eyes, no one would say that it would have been normatively objectionable. To the contrary, administrative sabotage of the Fugitive Slave Act would have vindicated the Constitution’s highest ideals. Arguments in favor of the Justice Department’s refusal to defend the Defense of Marriage Act rely on the same logic.71E.g., Joseph Landau, Presidential Constitutionalism and Civil Rights, 55 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1719 (2014).

But we should be clear about the logic of these arguments. The claim is not that sabotage is compatible with the constitutional scheme. It is that, in extraordinary circumstances, sabotage may be justified despite its tension with that scheme.

D. Sabotage’s Legal Position

Although sabotage is objectionable on both constitutional and democratic grounds, it does not follow that courts will stop agencies from engaging in it. In this Section, I argue that sabotage exists in a kind of legal grey area—formally incompatible with the Constitution and agencies’ authorizing legislation, but mostly insulated from judicial scrutiny. This immunity reflects courts’ hesitance to engage the question whether agency action is sabotage. Because of that hesitance, challenges to administrative sabotage cannot rely solely on the fact that it is sabotage.

I first explain the evidentiary and separation of powers problems that prevent courts from inquiring into whether agency action aims to kill or nullify a statutory program. I then trace how those problems inform doctrine under the Take Care Clause and § 706 of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), the two bodies of law that provide the most obvious avenues for challenging administrative sabotage in court. Finally, I discuss three recent cases in which litigants unsuccessfully challenged agency actions on the ground that they were sabotage.

1. Evidentiary and Separation of Powers Obstacles to Judicial Review of Agency Sabotage

The understanding of administrative sabotage developed in this Part implies that agency officials act in a particular kind of bad faith when they engage in sabotage: officials charged with administering a statutory program instead use authority created by law to attack it.

As I argued above, the bad faith inherent in administrative sabotage is at odds with the Constitution’s Take Care Clause.72U.S. Const. art. II, § 3. It also conflicts with specific delegations of statutory authority to agencies. When Congress charges an agency with ensuring “that markets for consumer financial products and services are fair, transparent, and competitive”7312 U.S.C. § 5511(a). or with setting air pollution limits “requisite to protect the public health,”7442 U.S.C. § 7409(b)(1). it assumes that the agency will act in good faith to advance policy objectives defined by law. Administrative sabotage is not that. The entire point is to dismantle a disfavored program.

But for two reasons, courts are unlikely to invalidate agency action based on an agency’s failure to carry out a statutory mandate in good faith. The first obstacle is evidentiary. Officials sometimes acknowledge they are engaged in sabotage,75See Robert Pear & Reed Abelson, Foiled in Congress, Trump Moves on His Own to Undermine Obamacare, N.Y. Times (Oct. 11, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/11/us/politics/trump-obamacare-executive-order.html [perma.cc/9897-YJMK]. but it is simple to invent technocratic explanations for agency actions designed to undermine a statutory program, and government lawyers routinely offer such explanations in court.76See, e.g., Dep’t of Com. v. New York, 139 S. Ct. 2551, 2557 (2019) (noting the Trump administration’s contention that it sought to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census form “to use in enforcing the Voting Rights Act”); Trump v. Hawaii, 138 S. Ct. 2392, 2404, 2417 (2018) (crediting the Trump administration’s contention that a proclamation implementing Trump’s campaign promise to halt immigration from Muslim countries “sought to improve vetting procedures by identifying ongoing deficiencies in the information needed to assess whether nationals of particular countries present ‘public safety threats’”). This creates a difficult evidentiary problem for courts, because many tools of sabotage are also the stuff of good-faith policy implementation.

Courts can order discovery into agency decisionmakers’ subjective motivations, but this highlights the second obstacle. If assessing decisionmakers’ subjective reasons would not violate the separation of powers, it nevertheless requires courts to probe far into the administrative process. What were the relevant decisionmakers’ thinking at the time of the agency’s action? Do they take the oath of office seriously? Are they telling the truth?

Courts traditionally have avoided such inquiries and instead evaluated agencies’ explanations for their actions in light of the contemporaneous administrative record.77Dep’t of Com., 139 S. Ct. at 2573. As the Supreme Court explained in Department of Commerce v. New York, this approach to judicial review “reflects the recognition that further judicial inquiry into ‘executive motivation’ represents ‘a substantial intrusion’ into the workings of another branch of Government and should normally be avoided.”78Id. (quoting Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hous. Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 268 n.18 (1977)). To respect the executive branch’s prerogatives, courts afford agency actions a “presumption of regularity.”79Note, The Presumption of Regularity in Judicial Review of the Executive Branch, 131 Harv. L. Rev. 2431, 2432 (2018).

The influence of these problems is apparent in doctrine interpreting the two bodies of law that provide the most obvious avenues for challenging administrative sabotage: the Take Care Clause and the APA.

2. The Take Care Clause

As already noted, the Take Care Clause obligates the president to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”80U.S. Const. art. II, § 3. Precedent interpreting the Take Care Clause does not answer many questions it raises.81See Goldsmith & Manning, supra note 67, at 1836–38. However, courts have traditionally held that the Clause provides an affirmative basis for relief only when an executive-branch actor is subject to a specific, nondiscretionary duty.82See, e.g., Detroit Int’l Bridge Co. v. Gov’t of Can., 189 F. Supp. 3d 85, 99 (D.D.C. 2016). This distinction traces to Marbury v. Madison, where Chief Justice Marshall distinguished between “cases in which the executive possesses a constitutional or legal discretion” and those in which “a specific duty is assigned by law, and individual rights depend upon the performance of that duty.” 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 166 (1803). When a court had jurisdiction, Marshall held, a writ of mandamus would issue only to correct violations of the latter category of duties. Id. at 169; see also Mississippi v. Johnson, 71 U.S. (4 Wall.) 475, 499 (1867) (reasoning that for a court to police the president’s performance of discretionary duties under the Take Care Clause would be “an absurd and excessive extravagance” (quoting Marbury, 5 U.S. at 170)). Absent such a duty, allegations that an executive-branch actor failed to execute the law in good faith do not state a claim upon which relief may be granted.83See Detroit Int’l Bridge Co., 189 F. Supp. 3d at 99. Consistent with this view, claims that an executive-branch actor violated the Clause by implementing statutory policy in bad faith appear to be a nonstarter. My research did not locate a single case in which a federal court held that the president or an agency acting under his control violated the Take Care Clause by failing to execute, administer, or enforce a duly enacted law in good faith.84Perhaps the closest that a court has come to affirmatively enforcing the Take Care Clause is National Treasury Employees Union v. Nixon, 492 F.2d 587 (D.C. Cir. 1974). That case involved President Nixon’s failure to implement a pay raise for federal employees that had been approved by Congress. Employees petitioned for a writ of mandamus compelling Nixon to implement the raise, as well as a declaratory judgment that Nixon had failed to comply with the law mandating the raise. Id. at 591. The court concluded that Nixon had unlawfully failed to implement the pay raise but felt compelled “to show the utmost respect to the office of the Presidency and to avoid, if at all possible, direct involvement by the Courts in the President’s constitutional duty faithfully to execute the laws.” Id. at 616. Accordingly, the court limited itself to issuing a declaratory judgment. Id.

3. Administrative Law

The same evidentiary and separation of powers concerns are reflected in doctrine interpreting the APA. The APA contains two chapters: one establishing procedures for “each authority of the Government of the United States,”855 U.S.C. § 551(1). and another that provides for review of agency action.86Id. §§ 701–706. The centerpiece of the chapter on judicial review, § 706, directs courts to hold unlawful and set aside agency action that is “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law.”87Id. § 706(2)(A).

By its terms, § 706 seems to apply to administrative sabotage: what greater “abuse of discretion” could there be than sabotaging a statutory program? But the black letter formulation of the arbitrary-and-capricious standard carefully avoids inquiry into executive motive—the crucial question in identifying sabotage. To withstand arbitrary-and-capricious review, an “agency must examine the relevant data and articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action including a ‘rational connection between the facts found and the choice made.’”88Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass’n v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29, 43 (1983) (quoting Burlington Truck Lines, Inc. v. United States, 371 U.S. 156, 168 (1962)). Moreover, judicial review ordinarily proceeds on the basis of a record compiled by the agency and submitted to the court.892 Kristen E. Hickman & Richard J. Pierce, Jr., Administrative Law Treatise § 10.5, at 1145–48 (6th ed. 2019). Only when a party makes a “strong showing of bad faith or improper behavior” may a court order discovery into “the mental processes of administrative decisionmakers.”90Citizens to Preserve Overton Park, Inc. v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 420 (1971).

Within this framework, a litigant challenging alleged sabotage cannot rest on the fact that the agency acted in bad faith but must also show that the challenged action is substantively unreasonable. The agency will defend its action as a permissible exercise of statutory discretion. Ordinarily, the litigant will not be allowed to go beyond the administrative record to rebut that defense.

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Department of Commerce v. New York potentially changes this equilibrium in recognizing “pretext” as a basis for finding agency action arbitrary and capricious.91See Dep’t of Com. v. New York, 139 S. Ct. 2551, 2576 (2019). At issue was the Commerce Department’s decision to include a citizenship question on the short-form 2020 census form.92Id. at 2561–62. Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Roberts held that the addition of the citizenship question was not “substantively invalid”—that is, that the addition of the citizenship question was within the Commerce Department’s statutory authority and satisfied the ordinary arbitrary-and-capricious standard.93Id. at 2571 (concluding that the decision to reinstate the citizenship question “was reasonable and reasonably explained, particularly in light of the long history of the citizenship question on the census”). But Roberts went on to hold that the citizenship question was unlawful “because it rested on a pretextual basis.”94See id. at 2573, 2576.

To reach this conclusion, the Court relied on extrarecord discovery that the district court ordered after finding that the Justice Department’s explanation of the Commerce Department’s actions involved bad faith or improper behavior.95Id. at 2573–74; see also New York v. U.S. Dep’t of Com., 339 F. Supp. 3d 144, 147 (S.D.N.Y. 2018), aff’d in part, rev’d in part sub nom. Dep’t of Com. v. New York, 139 S. Ct. 2551. That discovery revealed that Commerce went to “great lengths” to elicit a request to include the citizenship question from the Justice Department and that Commerce and Justice’s rationale for including the citizenship question—that citizenship data would “better enforce” the Voting Rights Act—was “contrived.”96Dep’t of Com., 139 S. Ct. at 2575. The Court remanded the matter to the Commerce Department because its “sole stated reason” for the addition of the citizenship question was pretextual.97Id.

Although a few examples of sabotage might be vulnerable to legal challenge on this ground, Department of Commerce will not have a major effect on judicial review of administrative sabotage. The Court’s conclusion depended on extrarecord discovery that the Supreme Court held was ordered prematurely.98See id. at 2574 (agreeing “with the Government that the District Court should not have ordered extra-record discovery when it did” but concluding that “the new material that the parties stipulated should have been part of the administrative record . . . largely justified such extra-record discovery as occurred”). More importantly, the Court held that “a court may not reject an agency’s stated reasons for acting simply because the agency might also have had other unstated reasons.”99Id. at 2573. Thus, while invalidating the particular abuse of power at issue in that case, Department of Commerce gave a roadmap for using agency power to attack statutory programs. In the future, an agency need only articulate a lawful statutory objective and support it with evidence to avoid the fate of the citizenship question.

4. Administrative Sabotage in the Courts

When we consider cases where litigants challenged agency action on the ground that it was sabotage, courts have not applied the Take Care Clause or § 706 to examine whether agencies were in fact engaged in sabotage. Instead, they have applied standard administrative law and jurisdictional doctrines to evaluate the lawfulness of agency action or find cases nonjusticiable.

In Texas v. United States, a coalition of states alleged that President Obama and agencies under him violated the Take Care Clause, the APA, and the Immigration and Nationality Act in promulgating the DAPA program, which temporarily exempted certain undocumented immigrants with American children from deportation.100Texas v. United States, 86 F. Supp. 3d 591, 614 (S.D. Tex.), aff’d, 809 F.3d 134 (5th Cir. 2015), aff’d by an equally divided court, 136 S. Ct. 2271 (2016). Quoting statements that Obama made during negotiations on a failed comprehensive immigration reform bill, the complaint alleged that the president “took an action to change the law.”101Complaint for Declaratory & Injunctive Relief at 3, Texas, 86 F. Supp. 3d 591 (No. 14-cv-00254) (emphasis omitted). The theory, Josh Blackman explains, was that DAPA amounted to “a deliberate effort to undermine the laws of Congress, not to act in good faith.”102Blackman, supra note 68, at 219.

The district court preliminarily enjoined DAPA on the ground that it should have been promulgated using notice-and-comment procedures.103Texas, 86 F. Supp. 3d at 677. A divided panel of the Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s ruling and added that DAPA was invalid because it conflicted with the Immigration and Nationality Act.104Texas v. United States, 809 F.3d 134, 178, 186 (5th Cir. 2015), aff’d by an equally divided court, 136 S. Ct. 2271 (2016). Both courts declined to address plaintiffs’ argument that “DAPA was not consciously and expressly adopted as a means to enforce the laws of Congress or to conserve limited resources.”105Blackman, supra note 68, at 216. The district court “specifically” noted that it was not addressing “Plaintiffs’ likelihood of success on their . . . constitutional claims under the Take Care Clause/separation of powers doctrine.” Texas, 86 F. Supp. 3d at 677. The Fifth Circuit found it “unnecessary, at this early stage of the proceedings, to address or decide the challenge based on the Take Care Clause.” Texas, 809 F.3d at 146 n.3.

City of Columbus v. Trump, decided four years later, followed the same pattern. A group of cities contended that President Trump and various agencies charged with administering the ACA had violated the APA and the Take Care Clause through “a relentless campaign to sabotage and, ultimately, to nullify the law.”106Complaint for Declaratory & Injunctive Relief at 1, City of Columbus v. Trump, 453 F. Supp. 3d 770 (D. Md. 2020) (No. 18-cv-02364). The complaint alleged that the Trump administration aimed “to pressure Congress to repeal the Act or, if that fails, to achieve de facto repeal through executive action alone.”107Id. It cited a variety of administrative and presidential actions that seemed to present clear-cut examples of sabotage.108See id. at 2 (detailing various agency actions that had “promot[ed] insurance that does not comply with the ACA’s requirements,” “slash[ed] funding for outreach strategies that have been proven to encourage individuals, and healthy individuals in particular, to sign up for coverage,” “misus[ed] federal funds for advertising campaigns aimed at smearing the ACA and its exchanges,” and “impos[ed] unnecessary and onerous documentation requirements”).

The district court dismissed plaintiffs’ Take Care claim because the complaint did not plausibly allege the violation of a nondiscretionary duty.109Columbus, 453 F. Supp. 3d at 803. The court allowed plaintiffs’ APA claims to proceed past a motion to dismiss.110Id. at 795–96. However, the court made clear that it would approach those claims as ordinary requests for judicial review of agency action.111Id. at 796 (reasoning that “dismissal based solely on [the complaint’s] contents would be premature here because a review of the administrative record is necessary to a determination of whether the Secretary’s methodology was arbitrary and capricious”). The court did not suggest that administrative sabotage, if proved, would violate the arbitrary-and-capricious standard.

In Maryland v. United States, the State of Maryland alleged that “the President and his administration have waged, and continue to wage, a relentless campaign to sabotage and nullify the ACA, through legislative and executive action.”112360 F. Supp. 3d 288, 312 (D. Md. 2019). Among other remedies, Maryland sought a declaration that would have precluded the administration from supporting a lawsuit designed to nullify the ACA.113Second Amended Complaint at 35, Maryland, 360 F. Supp. 3d 288 (No. 18-cv-2849). Citing the Take Care Clause, the district court acknowledged that the president’s authority to execute the laws “does not entail the authority to disregard a federal statute.”114Maryland, 360 F. Supp. 3d at 317. But the court ruled the case was not justiciable.115Id.

Under the law as it now stands, administrative sabotage is unlawful but unlikely to be remedied by the courts. Insofar as law regulates administrative sabotage, prohibitions of it have the status of an “underenforced” norm.116For a classic treatment of this concept, see Lawrence Gene Sager, Fair Measure: The Legal Status of Underenforced Constitutional Norms, 91 Harv. L. Rev. 1212 (1978). From the standpoint of constitutional and administrative law doctrine, an allegation that an agency is engaged in sabotage is sauce on the main dish. The allegation might affect how a court applies standard review doctrines. In itself, it is unlikely to provide a basis for judicial relief.

II. The Political Economy of Administrative Sabotage

Case studies such as the CFPB’s attack on the Consumer Financial Protection Act under Mick Mulvaney and the Trump’s administration’s assault on the ACA provide empirical evidence that administrative sabotage is an actual phenomenon. But why administrative sabotage happens is still something of a theoretical puzzle.

Consider William Niskanen’s “budget maximizing” theory of the bureaucracy.117See Niskanen, supra note 26. Niskanen posited that agency employees want the same material goods as most people.118See id. at 40 (pointing to greater opportunities for promotion and greater job security as reasons for agency employee interest in larger budgets). While an agency does not generate profits that it can pass on to owners and employees, it possesses private information about the cost of regulating that it can use to dupe Congress into increasing its budget.119See id. at 29. Bigger budgets, Niskanen posited, filter down to agency employees in the form of higher wages, better work, and nicer parking spots.120See id. at 40. So Niskanen predicted that bureaucrats would “maximize the total budget of their bureau during their tenure.”121Id. at 42.

For a Niskanenian agency, administrative sabotage is irrational. Why would a budget-maximizing agency attack the very programs it administers—up to requesting nothing to fund its operations?

To answer that question, it helps to move beyond simplified theories of the bureaucracy and situate sabotage within larger trends in American politics, legislation, and administrative policymaking. In this Part, I sketch a theory of sabotage’s origins in three such trends: ideological opposition to an activist federal government, the “stickiness” or entrenchment of programs that are enacted into law, and the rise of an administrative state that is highly responsive to the president’s preferences.

In brief, the argument is that sabotage is the product of the incentives, constraints, and powers of the modern presidency. Presidents face intense pressure to retrench statutory programs, but the textbook lawmaking process is difficult and politically costly to navigate.122For the distinction between “textbook” and “unorthodox” lawmaking processes, see Barbara Sinclair, Unorthodox Lawmaking (5th ed. 2017). Facing this dilemma, the administrative state offers presidents an alternative way of attacking statutory programs that imposes fewer barriers to action than, and offers many of the same rewards as, formal statutory retrenchment.

Sections II.A and II.B review the dilemma for presidents created by political demands for statutory retrenchment and a legislative process that makes satisfying those demands difficult. Section II.C shows how presidents, caught on the horns of this dilemma, use control of agencies to pursue retrenchment that they are unwilling or unable to get from Congress.

A. Demand for Statutory Retrenchment

Administrative sabotage is a mechanism for deconstructing, dismantling, rolling back, or minimizing federal statutory programs. As such, it must be understood within the context of broader opposition to federal state-building in the United States. Theoretically, such opposition might come from either the political left or the right. But for complicated historical reasons, opposition to federal legislation and regulation comes predominantly from the right. Thus, while left-wing politics occasionally generates demands to dismantle statutory programs,123See, e.g., A. Naomi Paik, Abolitionist Futures and the US Sanctuary Movement, Race & Class, Oct.–Dec. 2017, at 3. sabotage is an “asymmetric” phenomenon that is most likely to occur under conservative presidents.124Cf. Joseph Fishkin & David E. Pozen, Essay, Asymmetric Constitutional Hardball, 118 Colum. L. Rev. 915 (2018) (positing a similar asymmetry in use of “constitutional hardball”); Matt Grossmann & David A. Hopkins, Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats 14 (2016) (showing that the parties are asymmetric in their composition, approach to politics, and policymaking stances).

A few key moments in modern political history underscore the parties’ asymmetric incentives to engage in administrative sabotage. In the decades after World War II, the Republican Party was captured by the modern conservative movement.125See generally Grossmann & Hopkins, supra note 137; Heather Cox Richardson, To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party (2014). Among the movement’s defining positions is a commitment to freedom, individualism, and economic liberty.126See generally Elizabeth A. Fones-Wolf, Selling Free Enterprise: The Business Assault on Labor and Liberalism, 1945–60 (1994). While this free-market, antiregulatory philosophy has been central to conservative politics since the New Deal, Republican officeholders “have increasingly embraced a highly confrontational approach that eschews inside strategies premised on the pursuit of compromise in favor of maximizing partisan conflict, emphasizing symbolic acts of ideological differentiation, and engaging in near-automatic obstruction of initiatives proposed by the opposition.”127Grossmann & Hopkins, supra note 137, at 12. After the Tea Party helped Republicans retake control of the House in 2010, members’ votes increasingly aligned with Tea Party demands on both substantive and procedural issues.128Rachel M. Blum, How the Tea Party Captured the GOP 87–89 (2020); Fishkin & Pozen, supra note 137, at 933; Theda Skocpol & Vanessa Williamson, The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism 4 (2012).

As illustrated by a Tea Partier’s demand to “keep the government’s hands off my Medicare,” conservative opposition to federal regulation is both selective and informed by race, class, and notions of deservingness.129See Skocpol & Williamson, supra note 141, at 60, 79–80. For a somewhat sympathetic account of these attitudes, which hesitates to ascribe them entirely to racial prejudice, see Katherine J. Cramer, The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker (2016). Thus, conservative demands to retrench federal regulation have not translated into demands to, say, eliminate interior immigration enforcement or defund the police.130In fact, the size of the federal government has grown during periods of Republican control. See, e.g., Lisa Rein, The Federal Government Puts Out a ‘Help Wanted’ Notice as Biden Seeks to Undo Trump Cuts, Wash. Post (May 21, 2021, 6:00 AM), https://washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/05/21/biden-trump-government-rebuilding [perma.cc/6HDS-LYF7] (noting that size of federal bureaucracy grew 3.4 percent during Trump administration). Even so, opposition to federal regulation remains a defining feature of conservative politics.

This stance was prominent in the early days of the Trump administration. On the heels of Trump’s electoral college victory, Steve Bannon vowed the new administration would fight for the “deconstruction of the administrative state.”131Max Fisher, Stephen K. Bannon’s CPAC Comments, Annotated and Explained, N.Y. Times (Feb. 24, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/24/us/politics/stephen-bannon-cpac-speech.html [perma.cc/723T-ZZ6N]. “The way the progressive left runs,” Bannon argued, “is if they can’t get it passed, they’re just going to put in some sort of regulation in an agency.”132Id. Bannon promised: “That’s all going to be deconstructed and I think that’s why this regulatory thing is so important.”133Id.

B. Sticky Legislation

Politics may generate intense demand for presidents to dismantle statutory programs, but how to satisfy that demand is easier asked than answered. For reasons familiar to scholars of deregulation, repealing enacted programs is both difficult and politically treacherous.134See, e.g., Farhang, supra note 22, at 38; Paul Pierson, Dismantling the Welfare State? Reagan, Thatcher, and the Politics of Retrenchment 18 (1994); Herbert Kaufman, Brookings Inst., Are Government Organizations Immortal? (1976). Enacted programs thus tend to become “sticky” or entrenched.135See Bryan D. Jones, Tracy Sulkin & Heather A. Larsen, Policy Punctuations in American Political Institutions, 97 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 151, 151–52 (2003).

This stickiness has both structural and psychological explanations.136See Pierson, supra note 147, at 17–19; Jones et al., supra note 148. As for structure, the many “veto points” in the federal legislative process insulate enacted programs from repeal.137See generally George Tsebelis, Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work (2002) (showing how changing the legislative status quo requires that a certain number of “veto players” in the political system agree to the change). Suppose Congress enacts a new federal program. Following an election, party control of Congress switches, but the prior majority party still controls a veto point such as the Senate filibuster. Control of that veto point allows lawmakers now in the minority to protect the new program.

The psychological explanation involves the way that “loss aversion” interacts with interest group dynamics.138See Pierson, supra note 147, at 18. Organizing collective action is a major obstacle to passing any legislation.139The classic work developing this point is Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action (1965). As Olson explains, someone seeking to persuade Congress to enact legislation must coordinate the actions of thousands of people and pay for collective goods such as legislative drafting and lobbying that no individual would rationally subsidize. Cutbacks to statutory programs, however, “generally impose immediate pain on specific groups, usually in return for diffuse, long-term, and uncertain benefits.”140Pierson, supra note 147, at 18. A credible threat to repeal a statutory program—at least one that generates benefits for statutory beneficiaries—can accordingly be expected to mobilize intense interest-group opposition.141Id. at 19–24.

The unsuccessful effort to “repeal and replace” the ACA illustrates these dynamics.142See Jacob S. Hacker & Paul Pierson, The Dog That Almost Barked: What the ACA Repeal Fight Says About the Resilience of the American Welfare State, 43 J. Health Pol. Pol’y & L. 551 (2018). In the 2016 election cycle, virtually every Republican candidate ran on a platform of repealing “Obamacare.”143David A. Fahrenthold & Jenna Johnson, Republicans’ Obamacare ‘Repeal and Replace’ Dilemma Joins Presidential Contest, Wash. Post (Aug. 18, 2015), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/health-law-repeal-and-replace-joins-republican-presidential-contest/2015/08/18/b620ee94-45ce-11e5-846d-02792f854297_story.html [perma.cc/7TTH-ZBCU]. President Trump’s victory gave Republicans control of the House, Senate, and presidency. But the House’s passage of legislation repealing the ACA triggered a massive mobilization to defend the law.144Christopher Ingraham, Here’s a List of Medical Groups Opposing the Cassidy-Graham Health-Care Bill, Wash. Post (Sept. 22, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/09/22/heres-a-list-of-medical-groups-opposing-the-cassidy-graham-health-care-bill [perma.cc/K62X-8KU9]; Hacker & Pierson, supra note 155, at 552. With Republicans divided between far-right factions that favored using the ACA repeal to roll back Medicare and Medicaid and centrists who favored more modest reforms, the repeal effort culminated in a dramatic early morning vote on July 28, 2017.145The “Skinny Repeal” attempted to bridge differences among congressional Republicans by repealing central parts of the ACA while putting off the design of replacement legislation. See H.R. 1628, 115th Cong. (2017); see also Mary Ellen McIntire, McConnell Reveals ‘Skinny’ Bill Text as Midnight Vote Looms, Roll Call (July 27, 2017, 10:51 PM), https://www.rollcall.com/2017/07/27/mcconnell-reveals-skinny-bill-text-as-midnight-vote-looms [perma.cc/LY45-62Q4]. With a simple thumbs down, Senator John McCain killed the “Skinny Repeal,” effectively ending congressional efforts to repeal the ACA.146Peter W. Stevenson, How John McCain’s ‘No’ Vote on Health Care Played Out on the Senate Floor, Wash. Post (July 28, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/07/28/how-john-mccains-no-vote-on-health-care-played-out-on-the-senate-floor [perma.cc/J564-88TD].

This is not to say that enacted programs are set in stone. Scholars have found that, on some measures, restructuring or termination of statutory programs is commonplace.147Christopher R. Berry, Barry C. Burden & William G. Howell, After Enactment: The Lives and Deaths of Federal Programs, 54 Am. J. Pol. Sci. 1 (2010). But the failed ACA repeal highlights the barriers a president must overcome to successfully unwind an enacted program. In 2016 and 2017, Republicans ran on an anti-ACA platform, unified around the necessity of repealing the law, and controlled Congress, the presidency, and the Supreme Court. Even with these advantages, repeal proved impossible.

C. The Administrative State as a Tool of Statutory Retrenchment

Imagine you are a president—probably a conservative one—elected with a mandate to roll back a statutory program. Opposition to the program is central to your political appeal, and voters expect you to use the presidency to deliver promised statutory retrenchment. But a credible threat to repeal the program will mobilize intense interest-group opposition. Even if your party controls Congress, the repeal effort is likely to fail. All of this imposes political costs, diverting time and attention from other priorities and contributing to a perception of fecklessness.

The basic logic of administrative sabotage is to use administrative agencies to do what is difficult or costly to accomplish through Congress. Through control of administrative agencies, the president can kill or nullify a statutory program or lay the groundwork for its repeal or nullification by Congress or the courts. Seen from this perspective, the fact that presidents engage in sabotage reflects the comparative costs and benefits of different modes of retrenching programs they don’t like. All else being equal, presidents might prefer to retrench statutory programs through formal legislation. When that is difficult or politically costly, administrative sabotage offers a close substitute.

Part III surveys tools available to a motivated administration to sabotage a statutory program. This Section works with a wider lens and considers the structural conditions that allow presidents to engage in administrative sabotage. Five features of the contemporary administrative state—none of which is sufficient in itself—facilitate sabotage.

1. Delegation

To begin, administrative sabotage takes advantage of Congress’s creation of agencies and departments and its broad delegations of statutory authority to them. Since the New Deal, Congress has created scores of agencies and executive departments and granted them power to regulate particular domains, at times through open-ended delegations.148See, e.g., U.S. Gov’t Manual (Nov. 2020 ed. 2020), https://www.usgovernmentmanual.gov [perma.cc/V8FT-STAS] (listing some four hundred federal administrative agencies). Contrary to critics, the story of congressional delegation is not one of ever-increasing agency power.149In the leading empirical study of congressional delegation, David Epstein and Sharyn O’Halloran found that major statutes’ “delegation ratio” (a measure of the discretion that Congress allowed agencies to exercise) declined slightly in the second half of the twentieth century. Epstein & O’Halloran, supra note 23, at 114–16. Later studies are consistent with Epstein and O’Halloran’s finding that Congress adjusts the amount of authority it delegates to agencies in response to information problems, the area in which Congress is regulating, and changes in party control of Congress and the executive branch. See, e.g., Jordan Carr Peterson, All Their Eggs in One Basket? Ideological Congruence in Congress and the Bicameral Origins of Concentrated Delegation to the Bureaucracy, 7 Laws art. 19, https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7020019; Kathleen M. Doherty & Jennifer L. Selin, Does Congress Differentiate? Administrative Procedures, Information Gathering, and Political Control (Mar. 27, 2015) (unpublished manuscript) (on file with the Michigan Law Review). But there are enough statutory delegations—and they are sufficiently flexible—to allow agencies to sabotage important statutory programs.

2. Presidential Administration

If agencies were led by individuals who were committed to implementing statutory mandates in good faith, Congress’s delegations of authority would not create a risk of sabotage. But rather than empower independent administrators, public law in recent decades has expanded the president’s control over them. When presidents face pressure to dismantle statutory programs, presidential administration is a transmission belt for sabotage.