A Republic of Spending

Large-scale spending measures make up many of Congress’s most important recent contributions to national policymaking. Congress has appropriated trillions of dollars to respond to emergencies, fight climate change, expand social safety net programs, spur technological innovation, and strengthen national infrastructure. While the contemporary Congress’s failure to enact landmark regulatory statutes causes many to characterize it as dysfunctional, Congress in fact remains quite active—its policymaking energy is simply concentrated in the spending domain.

Congress’s use of spending rather than regulatory legislation as its primary way of shaping national policy marks a significant shift in American governance. This Article examines the causes and consequences of that change. For Congress itself, spending has several advantages over regulatory lawmaking: spending measures can circumvent the Senate filibuster, changes in both political parties have tilted the political playing field toward spending, public choice dynamics often make spending more attractive to Congress than regulating, and spending is much less vulnerable than regulation to constitutional judicial review. But from the standpoint of the public interest, there is reason for concern about spending eclipsing regulatory legislation. Spending alone does not allow Congress to address all policy problems, and many pressing national issues cannot be remedied through spending. Spending also does not always allow Congress to deploy the most effective solutions to those problems that it does address. Moreover, normative arguments in favor of spending over regulation, such as arguments based on liberty or democracy, are weaker than they appear at first glance.

This account holds several lessons for a public law literature that has too often marginalized Congress. The spending domain provides a case study of Congress acting as a central national policymaker with the judiciary playing only a marginal role; it thus illustrates a road not traveled for our otherwise court-centered constitutional system. More practically, in the face of obstacles to regulatory legislation, spending can provide Congress with a meaningful (if indirect) way of advancing regulatory goals. Institutions and doctrines change over time, however, and greater congressional reliance on spending could lead to future efforts—most notably in the courts—to narrow Congress’s spending power.

Introduction

Congress is unproductive and dysfunctional, or so the conventional wisdom goes. Critics charge an often-gridlocked Congress with being a “broken branch” that is unable to confront national challenges.1 Thomas E. Mann & Norman J. Ornstein, The Broken Branch: How Congress Is Failing America and How to Get It Back on Track (2006); see also Thomas E. Mann & Norman J. Ornstein, It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided with the New Politics of Extremism (2012); Sarah Binder, The Dysfunctional Congress, 18 Ann. Rev. Pol. Sci. 85 (2015); Nolan McCarty, Polarization, Congressional Dysfunction, and Constitutional Change, 50 Ind. L. Rev. 223 (2016).

Today’s Congress, on this gloomy account, contrasts with that of earlier generations. Congress once produced a “Republic of Statutes”2See William N. Eskridge, Jr. & John Ferejohn, A Republic of Statutes: The New American Constitution (2010); see also Guido Calabresi, A Common Law for the Age of Statutes (1982).

—landmark laws so important that they “supplement[ed] and often supplant[ed] [the] written Constitution as to the most fundamental features of governance.”3 Eskridge & Ferejohn, supra note 2, at 12–13.

But over the course of the last half-century, the narrative goes, Congress lost the ability to legislate. The result is a shift in power toward the executive branch, the courts, and subnational governments.4See infra note 341 and accompanying text.

Public law scholarship often takes this dim view of Congress and, as a result, focuses much less on our legislative branch than on its executive and judicial counterparts.5See, e.g., Edward L. Rubin, Statutory Design as Policy Analysis, 55 Harv. J. on Legis. 143, 144–45 (2018) (describing public law scholarship’s neglect of Congress).

This account resonates with Congress’ failure to enact major regulatory statutes on a host of pressing issues: climate change, immigration, gun violence, and voting rights, among others. But it largely neglects Congress’s spending power. Many of Congress’s most important policy interventions take the form of spending, rather than regulating either directly or through delegations to agencies. Congress has exercised the power of the purse since the Founding. More recently, though, it has begun to spend record sums—including by enacting multiple bills spending more than a trillion dollars each—and many of its most high-profile legislative achievements in the twenty-first century have involved spending. Congress has spent trillions of dollars to respond to emergencies,6Notable, in this regard, is fiscal legislation enacted in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. See CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, 134 Stat. 1182 (2020); American Rescue Plan of 2021, Pub. L. No. 117-2, 135 Stat. 4.

expand social safety net programs,7See Honoring our PACT Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-168, 136 Stat. 1759.

spur scientific research and technological innovation,8See CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-167, 136 Stat. 1366.

and strengthen the nation’s physical infrastructure.9See Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Pub. L. No. 117-58, 135 Stat. 429 (2021).

It has also used spending to address some policy problems traditionally thought to be more fitting subjects for regulation, most notably climate change.10See Inflation Reduction Act, Pub. L. No. 117-169, 136 Stat. 1818 (2022).

All told, recent Congresses have spent a staggering amount of money. To be sure, the American welfare state is still smaller than those of peer nations,11See infra note 304 and accompanying text.

and much of the Republican Party is committed to significant spending reductions.12See infra notes 172–173 and accompanying text.

Yet Congress has spent aggressively in pursuit of a wide variety of policy goals. This turn to spending was especially pronounced during the Covid-19 pandemic, but it would be a mistake to view it as a short-term trend. Analysis of the subject-matter of major statutes, the share of pages of enacted spending versus nonspending legislation, and the arc of overall federal spending together show that Congress has, over a period of decades, retained and at times expanded its ability to spend while becoming less productive in enacting regulatory legislation.13See infra Section I.B.

One reason for Congress’s turn to spending over regulatory legislation is simple: the filibuster. Senate rules impose a de facto supermajority requirement on regulatory legislation, with the body able to close debate and proceed to a final vote only with a three-fifths supermajority. The budget reconciliation process, however, allows Congress to circumvent this requirement for some spending measures. When the Senate is closely divided and the prospect of bipartisan cooperation on many issues is low, congressional leaders have little choice but to pursue spending rather than regulatory measures, at least when those regulatory measures are ones that divide the parties.14See infra Section II.A.

Important as the filibuster and reconciliation process are, there is much more to the story. Most major spending legislation passes not through reconciliation but rather through regular order, typically with significant bipartisan support.15 Megan S. Lynch, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R40480, Budget Reconciliation Measures Enacted into Law Since 1980 (2022), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R40480 [perma.cc/AEW6-ZCR9]; Bill Heniff, Jr., Cong. Rsch. Serv., RL30297, Congressional Budget Resolutions: Historical Information (2015), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL30297 [perma.cc/9FL8-5EZV].

Beyond the filibuster and reconciliation, then, what accounts for the turn to spending? Changing politics reinforce the trend toward spending, as the Democratic and Republican Parties have each become more open to large-scale spending, to differing degrees and for very different reasons.16See infra Section II.B.

Alongside these evolving politics are longstanding public choice insights that explain why Congress is often incentivized to enact spending rather than regulatory legislation: spending proposals are not as likely as regulatory ones to mobilize opposition from concentrated interests, the political costs of inaction to Congress are usually much higher for failing to spend than for failing to regulate, and spending bills typically provide legislators greater opportunity to claim credit for particularized benefits.17See infra Section II.C.

Further, Congress legislates in the shadow of future judicial review, and constitutional doctrine curbs Congress’s ability to enact regulatory legislation while largely leaving its ability to spend money intact.18See infra Section II.D.

Together, Senate procedure, political changes, public choice dynamics, and the prospect of judicial review all point in the same direction: each makes spending more attractive to Congress than regulatory legislation.19This Article’s focus is on these legal and political dynamics. A separate story—more focused on economic factors—could be told about the role that an extended period of low interest rates and low inflation played in promoting spending, both in the United States and in many other nations as well. Incentives for government spending will greatest when legal, political, and economic factors are all aligned in favor of greater spending; incentives will be more mixed when economic factors make spending more costly even when law and politics favor spending. While I briefly touch on economic factors in the discussion that follows, see infra notes 163, 169–171, 201 and accompanying text, my focus is primarily on law and politics rather than economics.

What should we make of these dynamics? Spending is a critically important policymaking tool, and Congress’s ability to spend money should not be taken for granted. Spending can address pressing policy problems, promote the general welfare, and advance equality. A Congress unable to spend money would represent a significant failure of governance. Continued spending activity by Congress represents one of the first branch’s essential powers and serves as a counterweight to executive and judicial power in other domains.

A Congress that can much more readily spend money than enact regulatory legislation is severely limited, however. Most obviously, Congress is able and incentivized to address policy problems that can be tackled through spending rather than those that call for regulation. But prioritizing spending can prevent Congress from tackling a range of critical issues, such as immigration policy, criminal justice policy, the soundness of the financial system, the safety of consumer products, labor-management relations, regulation of artificial intelligence and biotechnology, and voting rights and other democracy reforms.20See infra text following note 285.

In the face of persistent worry about the stability of the financial system, the fate of the American worker, the threats of new technologies, and the potential for democratic backsliding, Congress’s frequent inability to deliver legislation on those and other issues may lead citizens to question whether it is capable of addressing the most important national problems. Legislative inaction on those topics may be one reason congressional approval has been conspicuously low for nearly two decades.21See Congress and the Public, Gallup, https://news.gallup.com/poll/1600/congress-public.aspx [perma.cc/FF8D-5CVE] (showing congressional approval ratings mostly in the teens and twenties from 2005–23).

In Richard Pildes’s words, “when democratic governments cannot deliver effectively on issues many of their members care most urgently about, that failure can lead at a minimum to distrust, alienation, withdrawal, anger, and resentment.”22Richard H. Pildes, The Neglected Value of Effective Government, 2023 U. Chi. Legal F. 185, 186 (2024).

Even for those policy challenges that Congress can address through spending, there is a problem with Congress’s inability to pass many sorts of regulatory interventions. At times, regulatory legislation could be more effective or efficient than spending as a means of accomplishing a given goal. In other instances, legislation that combines spending and regulatory interventions could be superior to spending alone.23See infra notes 286–292 and accompanying text.

Even for those who celebrate Congress’s investments to speed the clean energy transition, those investments would be even more potent if paired with certain stricter regulatory requirements. At times, the barriers to enacting regulatory legislation mean that Congress—even if it can pass spending measures—must make policy with one hand tied behind its back.

In a normative register, neither welfarist nor egalitarian theories provide support for a strict priority of Congress spending rather than regulating; to the contrary, regulatory legislation can be critical to both welfarist and egalitarian aims.24See infra Sections III.A–B.

Despite some countervailing arguments sounding in ideas of coercion and democracy, it is hard to justify the asymmetry that currently exists between spending and regulatory legislation.25See infra Sections III.C–E.

And a Congress that can only spend but not enact regulatory legislation, even when such legislation is popular and would address pressing national problems, is a Congress that will fail to earn the faith of the American public as an effective organ of government.26In some sense, a spending-focused Congress is a reversion to the norm, relative to the long sweep of American history. The period of the 1930s to 1970s was characterized by a large burst of regulatory lawmaking, but scholars have described that period as an anomalous part of our history. See Jefferson Cowie, The Great Exception: The New Deal & the Limits of American Politics 9 (2016) (arguing that “the political era between the 1930s and the 1970s marks what might be called a ‘great exception’—a sustained deviation, an extended detour—from some of the main contours of American political practice . . . .”); Bryan D. Jones, Sean M. Theriault & Michelle C. Whyman, The Great Broadening: How the Vast Expansion of the Policy-Making Agenda Transformed American Politics 1 (2019) (describing the causes and consequences of the “Great Broadening” of the late 1950s to 1970s, during which “the United States experienced a vast expansion in the national policy-making agenda” that entailed “getting involved in new issues where it had only limited presence before”).

A close examination of the law and politics of congressional spending holds several lessons for public law more generally. Congress has not disappeared from the lawmaking process, as many assume, but has rather remained active—mainly by enacting spending bills rather than the landmark regulatory statutes of past eras. Neglecting spending leads to underselling the importance of Congress in the contemporary separation of powers system.27See, e.g., Michael J. Teter, Congressional Gridlock’s Threat to Separation of Powers, 2013 Wis. L. Rev. 1097, 1127 (2013) (“[C]ongressional gridlock undermines the very tenets and assumptions of the separation of powers doctrine . . . .”).

The charge of congressional gridlock and the implications for our system of governance that flow from it may well hold true for regulatory lawmaking. But spending represents an important exception, a central function of government over which Congress still exercises significant power.28The legal literature contains a handful of important contributions that take Congress’s spending power seriously. See, e.g., Josh Chafetz, Congress’s Constitution: Legislative Authority and the Separation of Powers 45–77 (2017); Fiscal Challenges: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Budget Policy (Elizabeth Garrett, Elizabeth A. Graddy & Howell E. Jackson eds., 2008); Matthew B. Lawrence, Disappropriation, 120 Colum. L. Rev. 1 (2020); Kate Stith, Congress’ Power of the Purse, 97 Yale L.J. 1343 (1988); Charles Tiefer, Shutdown: How the Trump Shutdown Threatened the Fiscal Constitution, 46 U. Dayton L. Rev. 1 (2020). A related body of literature focuses on the public law of spending through the lens of the executive branch rather than Congress. See, e.g., Louis Fisher, Presidential Spending Power (1975); Gillian E. Metzger, Taking Appropriations Seriously, 121 Colum. L. Rev. 1075 (2021); Eloise Pasachoff, The President’s Budget as a Source of Agency Policy Control, 125 Yale L.J. 2182 (2016); Eloise Pasachoff, Executive Branch Control of Federal Grants: Policy, Pork, and Punishment, 83 Ohio St. L.J. 1113 (2022) [hereinafter Pasachoff, Federal Grants].

The law and politics of spending also point toward a road not traveled for public law more broadly in our age of juristocracy. Congress makes decisions about federal spending with little judicial oversight of those choices.29See infra Sections II.D, IV.A.

Regulatory policy, by contrast, is often functionally made by the executive branch, with significant supervision by the courts.30See, e.g., Kenneth S. Lowande & Sidney M. Milkis, “We Can’t Wait”: Barack Obama, Partisan Polarization and the Administrative Presidency, 12 Forum 3 (2014).

Congressional spending choices therefore offer a useful counterpoint to court-centered governance that leads us to take for granted the judiciary having the last word on many issues of regulatory policy.31See infra Section IV.A.

This Article’s analysis also points toward ways in which Congress can be an effective policymaker despite the forces that push it toward spending and make legislating on regulatory topics difficult. The most dramatic possible reform is a change to the filibuster to eliminate the asymmetry in how Senate rules treat spending and regulatory legislation. But more modest changes are possible as well. Congress could, for example, free up legislative capacity for regulatory action by reducing the amount of time that it devotes to spending matters. Further, even without any changes to the legislative process, Congress could advance many regulatory policy objectives through its power of the purse. Strategic uses of subsidies, conditional spending, and financial support for federal and state regulatory enforcement efforts are all potent tools when Congress cannot enact new regulatory statutes.32See infra Section IV.B.

A word on scope is in order before proceeding. This Article compares the legal and political dynamics of spending and regulatory legislation. I define federal spending broadly to include mandatory spending, discretionary spending, and those tax expenditures that serve as de facto spending even if no funds are drawn from the federal treasury.33See infra Section I.A.

By regulatory legislation, I mean legislation that imposes or modifies legal obligations, or creates or modifies legal entitlements.34Cf. H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law 81 (2d ed. 1994) (characterizing the “primary type” of legal rules as ones under which “human beings are required to do or abstain from certain actions, whether they wish to or not”).

On this expansive understanding, regulatory legislation includes not only paradigmatic regulatory statutes—such as financial regulatory statutes, environmental statutes, and health and safety statutes—but also civil rights statutes, voting rights statutes, and immigration statutes.35While most regulatory legislation regulates private parties, some regulates government actors. See, e.g., 52 U.S.C. § 10301 (barring subnational governments from enacting discriminatory voting rules).

A comparison between spending and regulatory legislation, broadly defined, allows for new insights about two of the major tools of congressional policymaking.

This analysis focuses on congressional spending itself, not on conditional spending statutes that do not themselves spend money but do impose legally binding requirements on recipients of federal funds.36See Albert J. Rosenthal, Conditional Federal Spending and the Constitution, 39 Stan. L. Rev. 1103, 1103–04 (1987) (“[Conditional] spending, at least as much as direct federal regulation, has played an increasingly large part in shaping the conduct of individuals, business organizations, and state and local governments.”).

Perhaps most notably, large swaths of federal civil rights law take this form. Institutions that receive federal financial assistance are barred from discriminating on the bases of race, sex, or disability, all pursuant to statutes that are triggered by the receipt of federal funding.3742 U.S.C. § 2000d (race); 20 U.S.C. § 1681(a) (sex); 29 U.S.C. § 794(a) (disability).

These sorts of statutes are not spending statutes but are rather regulatory statutes in which the regulated entity is the class of parties receiving federal financial assistance. My focus is on Congress spending money to advance particular policies or programs, not on statutes that impose regulatory requirements on all recipients of federal funds.38Two limitations of the present study bear mention, both arising from its focus on comparing spending and regulatory legislation. First, though I discuss some aspects of tax policy, I do not examine the politics of major tax legislation (such as the tax statutes enacted in 2001, 2003, and 2017), given the unique features of the tax legislative process that distinguish it from other sorts of congressional action. See generally George K. Yin & Lawrence A. Zelenak, Foreword: The Past, Present, and Future of the Federal Tax Legislative Process, 81 L. & Contemp. Probs., no. 2, 2018, at 1 (introducing a collection of essays on the topic). Second, my focus is on regulatory legislation, not regulatory actions undertaken by administrative agencies. Agency action is subject to its own set of legal and political constraints that do not exist for congressional action. See generally Stephen G. Breyer et al., Administrative Law and Regulatory Policy 209–754 (8th ed. 2017) (surveying constraints on agency action imposed by constitutional common law, the Administrative Procedure Act, and other statutes).

The Article proceeds as follows. Part I provides a brief overview of Congress’s spending power and its use of that power to pursue major policy objectives in recent years, including a case study of the turn to spending as Congress’s main tool for making climate policy. Part II examines the causes of the rise of spending as a primary tool of congressional policymaking, with a focus on legislative procedure, changing political conditions, public choice dynamics, and the shadow of constitutional law. I then shift from descriptive to normative analysis. Part III assesses the trends of persistent spending and reduced regulatory legislation, examining them from the standpoint of a range of normative values, including welfare, equality, liberty, and democracy. Part IV draws some broader lessons for public law, considers possible reform, and examines possible future directions for the law and politics of spending.

I. The Persistent Spending Power

A. Spending Power Basics

The Constitution empowers Congress to tax and spend.39 U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 1 (“The Congress shall have Power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States . . . .”).

This broad grant of authority contrasts with the limits on congressional power set out elsewhere in the Constitution: Congress can only enact regulatory legislation pursuant to one of its enumerated powers, but it can spend money in any way that advances the general welfare.40See United States v. Butler, 297 U.S. 1, 66 (1936) (“[T]he power of Congress to authorize expenditure of public moneys for public purposes is not limited by the direct grants of legislative power found in the Constitution.”). This decision represents a victory for Alexander Hamilton’s position in a Founding-era debate with James Madison over this issue. See Mark Seidenfeld, The Bounds of Congress’s Spending Power, 61 Ariz. L. Rev. 1, 3 n.5 (2019).

Courts defer to Congress’s determination that a given expenditure furthers the general welfare, leaving spending choices nearly entirely at Congress’s discretion.41South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203, 207 (1987) (“In considering whether a particular expenditure is intended to serve general public purposes, courts should defer substantially to the judgment of Congress.” (citing Helvering v. Davis, 301 U.S. 619, 640, 645 (1937))).

And Congress’s power to spend is exclusive: “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury,” Article I provides, “but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.”42 U.S. Const. art. I, § 9, cl. 7.

Though institutional details have changed, and interbranch power struggles have been the norm, Congress’s role as the only branch of government able to appropriate funds has been a constant throughout our history.43See Allen Schick, The Federal Budget: Politics, Policy, Process 8–27 (3d ed. 2007).

Broadly speaking, congressional spending bills come in two types: mandatory and discretionary. Mandatory spending is governed by statutory criteria, often set out in longstanding statutes, rather than through the annual appropriations process.44Frequently Asked Questions About CBO Cost Estimates, Cong. Budget Off., https://www.cbo.gov/content/what-difference-between-mandatory-and-discretionary-spending [perma.cc/S2CW-NXLL] (discussing the difference between mandatory and discretionary spending).

As a result, mandatory spending is typically ongoing and persists unless Congress changes the underlying statute that provides for the particular spending at issue. Mandatory spending—which includes Social Security, Medicare, and interest payments on the national debt—collectively accounts for nearly two-thirds of all federal spending.45 Walter J. Oleszek, Mark J. Oleszek, Elizabeth Rybicki & Bill Heniff Jr., Congressional Procedures and the Policy Process 44 (11th ed. 2020).

The remainder of federal spending is discretionary. Congress makes most appropriations on an annual basis,46See Schick, supra note 43, at 215 (“The Constitution does not require annual appropriations, but since the First Congress in 1789, the practice has been to appropriate each year.”).

though it sometimes enacts longer-term appropriations measures.47See Off. Gen. Couns., U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-16-464SP, Principles of Federal Appropriations Law 2–9 (4th ed. 2016) (discussing multiyear appropriations).

Spending touches nearly every area of federal policy: Congress funds the operation of federal agencies and the military, creates and sustains social welfare programs, provides funds to state and local governments, and supports scientific research.48Policy Basics: Where Do Our Federal Tax Dollars Go?, Ctr. on Budget & Pol’y Priorities (July 18, 2024), https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/where-do-our-federal-tax-dollars-go [perma.cc/25RN-EYW8] [hereinafter Where Do Our Federal Tax Dollars Go?].

When Congress creates grant programs, it can direct funds toward different sorts of recipients (such as states, localities, or private entities), make awards to all who meet eligibility criteria or instead through a competitive grant program, and provide funds on a one-time basis or in a more sustained way.49See Eloise Pasachoff, Agency Enforcement of Spending Clause Statutes: A Defense of the Funding Cut-Off, 124 Yale L.J. 248, 267–71 (2014) (discussing these and other choices in policy design).

Though discretionary spending makes up less than half of all federal spending, one of Congress’s primary functions is deciding which discretionary programs to fund and in what amounts.

Discretionary spending levels are typically set through the annual appropriations process, which is governed by a thicket of statutes, cameral rules, and longstanding norms.50See generally Schick, supra note 43 (describing the federal budget process).

But Congress frequently deviates from that process. It sometimes authorizes spending but does not subsequently appropriate funds.51See James V. Saturno & Brian T. Yeh, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R42098, Authorization of Appropriations: Procedural and Legal Issues 9–10 (2016), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R42098.pdf [perma.cc/6ZQG-9WYH]; see also Lawrence, supra note 28.

Conversely, it sometimes appropriates money without previous authorizing legislation, in excess of the amounts authorized, or after authorization has expired.52 Cong. Rsch. Serv., TE10005, Statement of Jessica Tollstrup, Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process, Before Committee on the Budget, U.S. Senate, Hearing on “Spending on Unauthorized Programs” 5–7 (2016).

Congress also enacts some high-profile spending measures outside of the normal appropriations process altogether.53See infra Section I.B (discussing recent spending bills enacted outside the normal appropriations process). Congress also sometimes provides for government operations to be funded through special channels: Social Security is funded through designated trust funds, 42 U.S.C. § 401, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is funded directly from the Federal Reserve, 12 U.S.C. § 5497.

And it sometimes uses appropriations bills to advance policy goals unrelated to spending, including through appropriations riders that can change substantive law.54See Neal Devins, Appropriation Riders, in 1 Encyclopedia of the American Presidency 67, 67–69 (Leonard W. Levy & Louis Fisher eds., 1994).

When Congress does not pass a regular appropriations measure, it generally enacts a continuing resolution, which provides temporary funding based on the previous year’s funding formula, often with some adjustments.55See James V. Saturno, Bill Heniff Jr. & Megan S. Lynch, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R42388, The Congressional Appropriations Process: An Introduction 13–14 (2016), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R42388.pdf [perma.cc/NNB2-RWNA].

A policymaking tool closely related to direct spending is tax expenditures, which take the form of tax deductions, exclusions, or exceptions for favored activities or entities. Major categories of tax expenditures include subsidies for home ownership, retirement savings, and charitable contributions, among many others.56See Grant A. Driessen, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R44530, Spending and Tax Expenditures: Distinctions and Major Programs 9–11 (2019), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44530/7 [perma.cc/YUT3-2C39].

It will often appeal to Congress to use tax expenditures, since doing so is a means of providing a subsidy without appropriating funds. As such, some (though not all) scholars view tax expenditures as tantamount to spending.57Compare Stanley S. Surrey & Paul R. McDaniel, Tax Expenditures 3 (1985) (defining tax expenditures as “departures from the normative tax structure [that] represent government spending for favored activities or groups, effected through the tax system rather than through direct grants, loans, or other forms of government assistance”), with Daniel N. Shaviro, Rethinking Tax Expenditures and Fiscal Language, 57 Tax L. Rev. 187, 188 (2004) (arguing that “[t]he basic claim of tax expenditure analysis, that certain tax rules are ‘really’ spending, is not quite correct, because ‘taxes’ and ‘spending’ are not coherent categories to begin with”).

In some key respects, tax expenditures more closely resemble mandatory rather than discretionary spending: Tax expenditures are not subject to the annual appropriations process, they usually persist unless modified or repealed, and any person or entity that meets applicable statutory requirements can claim the benefit of a tax expenditure.58See Christopher Howard, The Hidden Welfare State: Tax Expenditures and Social Policy in the United States 3–16 (1999).

B. Spending or Regulatory Legislation?

Historically, many of Congress’s most important policy achievements have been regulatory statutes. The past half-century, however, has witnessed a steady decline in Congress’s productivity in enacting such statutes. At the same time, Congress has continued to appropriate funds from the federal fisc, and recent years have featured multiple trillion-plus-dollar spending measures that eclipse spending in earlier eras. This section traces each of those shifts.

1. Declining regulatory legislation, persistent spending. Regulatory statutes are central to American law and touch nearly every area of life and commerce. Yet most landmark regulatory statutes are products of earlier eras: the Progressive Era,59See, e.g., Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, Pub. L. No. 59-384, 34 Stat. 768; Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, Pub. L. No. 63-203, 38 Stat. 717; Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, Pub. L. No. 63-212, 38 Stat. 730.

the New Deal,60See, e.g., Securities Act of 1933, Pub. L. No. 73-22, 48 Stat. 74; Banking Act of 1933, Pub. L. No. 73-66, 48 Stat. 162; Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Pub. L. No. 73-291, 48 Stat. 881; National Labor Relations Act of 1935, Pub. L. No. 74-198, 49 Stat. 449 (amended 1984); Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, Pub. L. No. 75-717, 52 Stat. 1040 (1938); Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, Pub. L. No. 75-718, 52 Stat. 1060.

and the 1960s and early 1970s.61See, e.g., Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241; Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, 79 Stat. 437; Fair Housing Act of 1968, Pub. L. No. 90-284, 82 Stat. 73; Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, Pub. L. 91-596, 84 Stat. 1590; Clean Air Amendments of 1970, Pub. L. No. 91-604, 84 Stat. 1676; Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-500, 86 Stat. 816; Endangered Species Act of 1973, Pub. L. No. 93-205, 87 Stat. 884.

Paradigm-shifting regulatory statutes from these periods—like the National Labor Relations Act, the Civil Rights Act, and the Clean Air Act—all seem beyond the reach of today’s Congress. One study of environmental lawmaking, for example, compared “[e]arlier Congresses” that were “celebrated for enacting sweeping, demanding environmental laws” with a contemporary “Congress [that] passes almost no coherent, comprehensive environmental legislation and displays no ability to deliberate openly and systematically in response to changing circumstances and new information.”62Richard J. Lazarus, Congressional Descent: The Demise of Deliberative Democracy in Environmental Law, 94 Geo. L.J. 619, 619 (2006).

Similar declines in legislative productivity exist in other areas. For decades, Congress has produced either minimal or no legislation across a host of major policy domains, including immigration,63See, e.g., Elaine Kamarck & Christine Stenglein, Can Immigration Reform Happen? A Look Back, Brookings (Feb. 11, 2019), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2019/02/11/can-immigration-reform-happen-a-look-back [perma.cc/55NG-GGRU] (“Bipartisan deals on immigration have eluded lawmakers and presidents for three decades.”).

labor,64The most significant recent push for labor law reform was the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, H.R. 842, 117th Cong. (2021). See Don Gonyea, House Democrats Pass Bill That Would Protect Worker Organizing Efforts, NPR (Mar. 9, 2021, 9:18 PM), https://www.npr.org/2021/03/09/975259434/house-democrats-pass-bill-that-would-protect-worker-organizing-efforts [perma.cc/C7UZ-FFCR]; see also Cynthia Estlund, The Supreme Court’s Labor and Employment Cases of the 2001–2002 Term, 18 Lab. Law. 291, 316 (2002) (“Congress has not enacted significant amendments to the [National Labor Relations Act] since 1959 . . . .”).

gun control,65See, e.g., Annie Karni & Luke Broadwater, A Timeline of Failed Attempts to Address U.S. Gun Violence, N.Y. Times (June 8, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/08/us/politics/gun-control-timeline.html [perma.cc/2S3P-WDCJ].

and voting rights.66For examples of such unsuccessful legislative efforts, see For the People Act, H.R. 1, 117th Cong. (2021), and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, H.R. 4, 117th Cong. (2021).

Empirical evidence supports the widely held view that Congress’s production of major regulatory statutes has slowed. David Mayhew, a leading political scientist, has compiled a comprehensive dataset of important statutes enacted from 1947 to 2018.67See Appendix, sec. A (describing the methodology for collecting and classifying statutes).

During the first half of that period (1947–82), Congress enacted fifty-seven important statutes imposing new regulatory requirements on the private sector or modifying the content of existing regulatory law.68This count excludes statutes that were primarily deregulatory, in the sense of relaxing or removing preexisting regulatory requirements.

During the second half of that period (1983–2018), Congress enacted only twenty-five such statutes. The dearth of major regulatory legislation since the 1980s is especially pronounced for the smaller subset of statutes that Mayhew defines as “historically important,” roughly one-tenth of his total. Of the twenty-four historically important statutes enacted during the second half of the time period covered by Mayhew’s data set (1983–2018), only two imposed significant new regulatory requirements: the Affordable Care Act69See Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010). Notably, the Affordable Care Act contained not only regulatory provisions (such as regulation of private insurers) but also new spending (such as the expansion of Medicaid).

and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.70See Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010).

Both were enacted in 2010, during a rare moment in which Democrats controlled the White House and held large majorities in the House and Senate.71See Jennifer E. Manning, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R40086 Membership of the 111th Congress: A Profile 1 (2010), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R40086.pdf [perma.cc/M25U-E423].

Nearly all legislation in recent decades that Mayhew classifies as historically important, however, has not resembled the landmark regulatory statutes of the mid-twentieth century. Of the historically important legislation that Mayhew identified from 1982–2018, fourteen statutes involved changes in spending policy, tax policy, or both; three had the main effect of removing existing regulatory requirements; and five related to foreign affairs or national security.72See Appendix, sec. A (listing historically important statutes in each of these categories).

Put simply, statutes that impose regulatory mandates make up a relatively small share of the most important contemporary legislation. The Mayhew data, though a crude measure in some respects, provides support for the widely held view that Congress has slowed in its pace of enacting significant regulatory statutes.73The limitations of the Mayhew data and this Section’s analysis suggest numerous directions for future empirical research. First, a fuller inquiry would examine not only enacted legislation (both spending and regulatory) but also failed legislative efforts, using a version of the methodology developed by Sarah Binder. See Sarah A. Binder, Stalemate: Causes and Consequences of Legislative Gridlock 35–40 (2003). Second, research could seek to quantify the relative importance of different legislative provisions, distinguishing between more and less important provisions (both spending and regulatory). Third, future work should look to the full extent of Congress’s work, beyond the subset of most important enactments examined by Mayhew. Some scholarship looking at overall legislative output (though not disaggregating spending and regulatory legislation) has showed a decline in Congress’s productivity. See, e.g., William Howell, Scott Adler, Charles Cameron & Charles Riemann, Divided Government and the Legislative Productivity of Congress, 1945–94, 25 Legis. Stud. Q. 285, 299 fig.3 (2000) (examining congressional enactments in the second half of the twentieth century for types of legislation not examined by Mayhew and observing a high-water mark of productivity in the 1960s and 1970s, followed by declines in subsequent decades). Fourth, scholars should seek to measure Congress’s practice of sometimes including regulatory provisions in must-pass spending bills rather than in stand-along regulatory bills. Each of these suggestions points toward how empirical scholars could undertake fuller analysis of changes in Congress’s productivity, but for present purposes I restrict myself to analysis based on the Mayhew data.

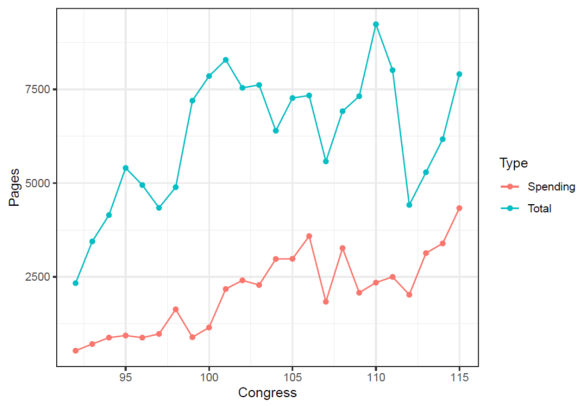

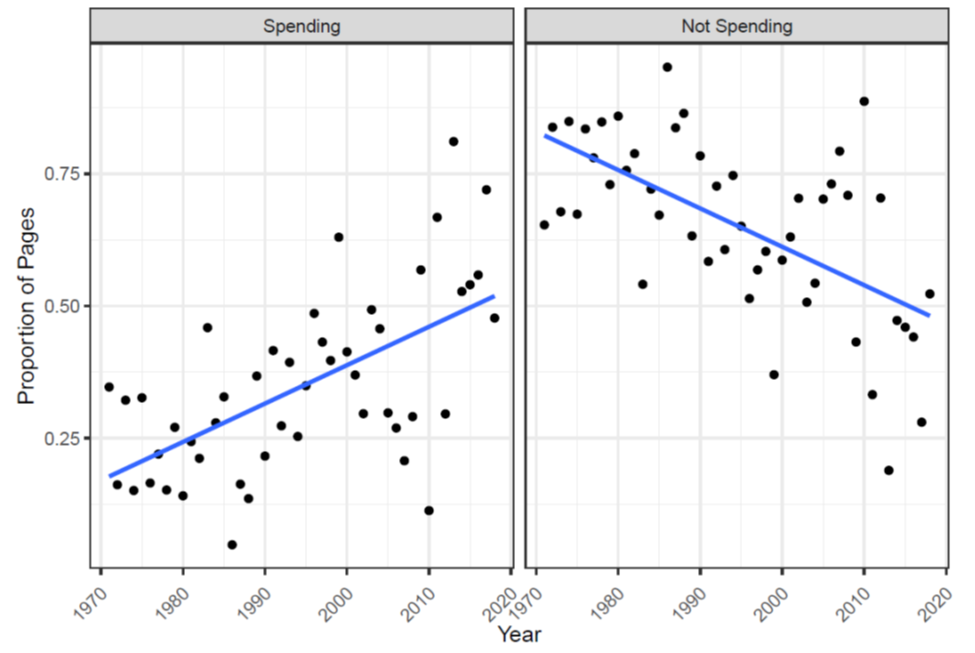

Additional analysis of Congress’s legislative output further supports the view that a greater share of Congress’s energy is going toward spending rather than regulatory legislation. One way of measuring how much of Congress’s attention is devoted to spending-related matters is by comparing the number of pages of legislative output of spending-related legislation to other types of legislation.74One empirical analysis finds, for example, that even as the number of laws enacted has declined, the number of pages of legislation has remained roughly constant since the 1980s. See James M. Curry & Frances E. Lee, The Limits of Party: Congress and Lawmaking in a Polarized Era 33–34 (2020). This analysis does not, however, account for pages of spending versus regulatory measures, or the number of provisions of either type.

Original empirical analysis, based on pages in the United States Statutes at Large, shows a steady increase in the share of spending-related legislation, as measured by legislative pages. In the 1970s and 1980s, spending-related statutes never made up more than half of total pages of legislative output, and often made up less than one-quarter of total pages. Pages of spending-related legislation first comprised around half of the total legislative output in the late 1990s. Several times in the 2010s, pages of spending-related legislation made up upwards of two-thirds of total legislative pages.75See Appendix, sec. B (presenting figures on this data and describing research methodology).

To be sure, measures of legislative pages are not a precise measure of how Congress is allocating its time or what its priorities are. Nor is the length of a statute a measure of its importance; some of the most important statutes are quite short. Nonetheless, changes in the number of legislative pages enacted over time is a standard metric used by political scientists studying legislative productivity.76See, e.g., Curry & Lee, supra note 74, at 33–34; E. Scott Adler & John D. Wilkerson, Congress and the Politics of Problem Solving 4 (2012); Paul J. Quirk, Deliberation and Decision Making, in The Legislative Branch 314, 327 (Paul J. Quirk & Sarah A. Binder eds., 2005).

And analysis of pages of spending-related versus other legislation demonstrates a clear trend toward Congress doing a greater share of its lawmaking through spending-related measures.

In terms of dollars, federal spending has continued apace even though Congress has at times struggled to enact spending legislation. Criticisms of the budget process are many: Congress routinely misses deadlines for enacting the annual budget resolution,77Molly E. Reynolds, What’s Wrong with the Congressional Budget Process?, Brookings: Unpacked (Nov. 3, 2017), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/whats-wrong-with-the-congressional-budget-process [perma.cc/2RGQ-9FKG].

it has not completed all of its spending bills on time since 1996,78Id.; see also McCarty, supra note 1, at 237–40.

it has become heavily reliant on continuing resolutions,79See Ellen Ioanes, How Congress’s Dependence on Short-Term Funding Keeps Us Stuck in the Past, Vox (Feb. 19, 2022, 5:43 PM), https://www.vox.com/2022/2/19/22941984/congress-government-funding-continuing-resolution-appropriations [perma.cc/MK5L-64SS].

and its failure to enact spending measures has led to costly government shutdowns.80See Clinton T. Brass et al., Cong. Rsch. Serv., RL34680, Shutdown of the Federal Government: Causes, Processes, and Effects 2–4 (2018), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL34680.pdf

[perma.cc/DSP9-9FYR]; see also infra notes 225–227 and accompanying text.

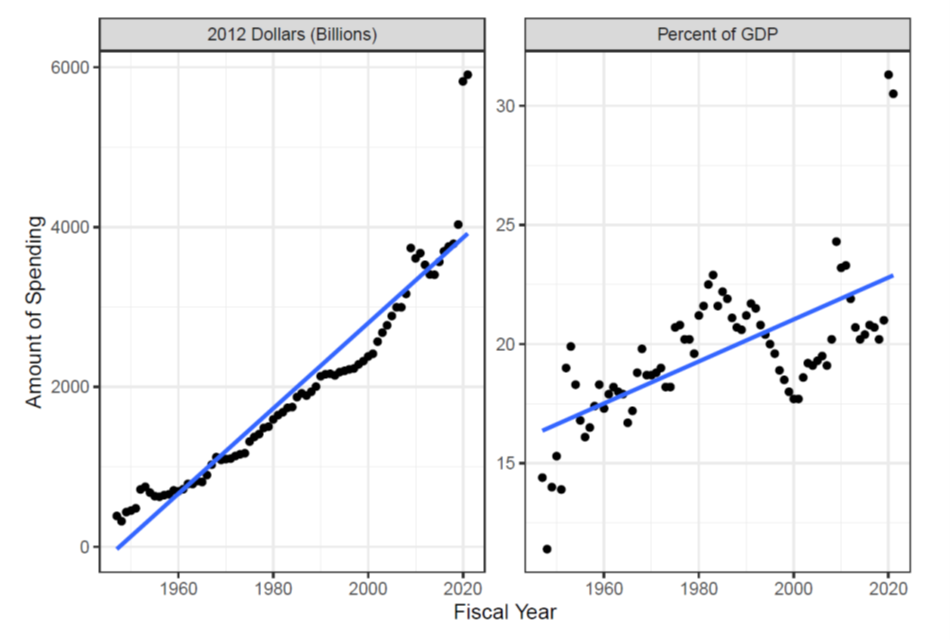

Despite these challenges, however, outlays steadily increased since the mid-twentieth century. Annual federal spending was generally less than $1 trillion from the end of World War II until the mid-1960s, $1–2 trillion from the mid-1960s to the late 1980s, $2–3 trillion in the 1990s and 2000s, and more than $3 trillion since (all figures in inflation-adjusted dollars).81See Table 1.3—Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-) in Current Dollars, Constant (FY 2012) Dollars, and as Percentages of GDP: 1940–2027, Off. Mgmt. & Budget (on file with author) (providing these figures, all of which are reported in 2012 dollars); see also Appendix, sec. C (charting change in federal spending over time).

Similar increases appear when evaluating spending as a percentage of GDP. Annual federal spending ranged from 13–23 percent of GDP during the second half of the twentieth century, has ranged from 17–32 percent of GDP in the twenty-first century, and has not fallen below 20 percent of GDP in any year since 2008.82See id.

The trend of generally rising federal spending holds across many policy areas, from national defense to health care, housing assistance to veterans’ benefits.83See Table 8.8—Outlays for Discretionary Programs in Constant (FY 2012) Dollars: 1962–2027, Off. Mgmt. & Budget (on file with author).

Nondefense discretionary spending as a percentage of GDP is lower than it was in the mid-twentieth century, but, except in times of emergency, it has consistently been roughly 3–4 percent of GDP since the 1980s.84See Ctr. on Budget & Pol’y Priorities, Policy Basics: Non-Defense Discretionary Programs 5 (2023), https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/PolicyBasics-NDD.pdf [perma.cc/5UVJ-FJ95].

Further, though Congress has occasionally attempted to create institutional rules to rein in spending, those efforts have largely failed.85The caps on discretionary spending set out in the Budget Control Act of 2011, Pub. L. No. 112-25, 125 Stat. 239, for example, were repeatedly adjusted by Congress in the years that followed, leading to almost trillion in additional spending, before expiring without being renewed. See Budget Roundup: Review of Almost Trillion in Cap-Adjusted Spending, U.S. Senate Comm. on the Budget: Chairman’s Press (Mar. 1, 2019), https://www.budget.senate.gov/chairman/newsroom/press/budget-roundup-review-of-almost-1-trillion-in-cap-adjusted-spending [perma.cc/FH8P-EUE5]; Megan S. Lynch & Grant A. Driessen, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R46752, Expiration of the Discretionary Spending Limits: Frequently Asked Questions 2 (2022), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46752 [perma.cc/YUT3-2C39]. Similarly, PAYGO budget rules have often been waived or inconsistently enforced, making them ineffective as a tool for limiting spending. See Tax Pol’y Ctr.’s Briefing Book 30 (2020), https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/briefing-book/tpc_briefing_book-may2022.pdf [perma.cc/EZ7Y-PFYM].

The result is continued spending—as a means of continuing to fund longstanding operations and programs, as a way for the majority party to fulfill various policy objectives, and as a response to emergencies.

2. Major new spending initiatives. The major legislative enactments of the first Trump and Biden Administrations exemplify Congress’s openness to large-scale new spending, even in the face of gridlock on many regulatory issues. Recent Congresses have spent record amounts of money, often on a bipartisan basis and often outside of the traditional budget process. Despite frequent changes in partisan control of both the executive and legislative branches, a common feature of the contemporary Congress is major new spending initiatives even as efforts to enact major nonspending (and nontax) legislation have often faltered.

A new wave of congressional spending began with the Covid-19 pandemic, under a Republican White House and Senate. In the first year of the pandemic, Congress enacted two major spending bills: the CARES Act,86Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020); see also Andrew Taylor, Alan Fram, Laurie Kellman & Darlene Superville, Trump Signs .2T Stimulus After Swift Congressional Votes, AP (Mar. 28, 2020, 12:09 AM), https://apnews.com/article/donald-trump-financial-markets-ap-top-news-bills-virus-outbreak-2099a53bb8adf2def7ee7329ea322f9d [perma.cc/8Z4B-WQ6L].

which totaled $2.2 trillion, and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021,87Pub. L. No. 116-260, 134 Stat. 1182 (2020).

which combined omnibus annual appropriations of $1.4 trillion with $900 billion in further pandemic relief measures.88Jeff Stein & Mike DeBonis, Senate Approves Huge Spending Package, Sends Economic Relief Measure to Trump for Enactment, Wash. Post (Dec. 22, 2020, 12:08 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2020/12/21/stimulus-congress [perma.cc/7ZXK-4XYH]; Caitlin Emma & Marianne Levine, Breaking Down the 0B Stimulus Package and .4T Omnibus Bill, Politico (Dec. 21, 2020, 11:48 PM), https://www.politico.com/news/2020/12/20/details-stimulus-package-omnibus-bill-449499 [perma.cc/39TD-X8R6].

The Covid-19 spending bills provided economic relief for individuals—in the form of stimulus checks for most Americans and expansions of unemployment insurance—along with financial support for businesses and subnational governments.89See Emily Cochrane & Sheryl Gay Stolberg, Trillion Coronavirus Stimulus Bill Is Signed into Law, N.Y. Times (Mar. 27, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/27/us/politics/coronavirus-house-voting.html [perma.cc/M2PL-L6GN]; Stein & DeBonis, supra note 88.

Those bills were heralded as “remarkable” for both their size and bipartisan support.90See, e.g., Amber Phillips, ‘Totally Unprecedented in Living Memory’: Congress’s Bipartisanship on Coronavirus Underscores What a Crisis This Is, Wash. Post (Mar. 26, 2020, 12:35 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/03/26/totally-unprecedented-living-memory-congresss-bipartisanship-coronavirus-underscores-what-crisis-this-is [perma.cc/26BX-TR9Y] (describing the CARES Act). But see Sharon Parrott et al., Ctr. on Budget & Pol’y Priorities, CARES Act Includes Essential Measures to Respond to Public Health, Economic Crises, but More Will Be Needed (2020), https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/3-27-20econ.pdf [perma.cc/CZ9L-5933] (criticizing the Act for not expanding SNAP benefits or covering costs of Covid-19 treatment for the uninsured).

Critically, they marked what some described as a sea change from Republicans’ traditional small-government stance, garnering the support of the sitting Republican president and nearly all congressional Republicans.91See Robert Costa & Philip Rucker, Trump’s Trillion Stimulus Is a Gamble for Reelection—And a Sea Change for Republicans Once Opposed to Bailouts, Wash. Post (Mar. 18, 2020, 6:44 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-coronavirus-economic-stimulus-reelection-bailout/2020/03/18/280a1a12-6947-11ea-9923-57073adce27c_story.html [perma.cc/LJ8A-TXNP].

The exceptional nature of the pandemic emergency certainly enabled these bills, but it does not detract from the massive scale and bipartisan nature of Congress’s response.

Congress continued to aggressively deploy its power of the purse in the early Biden Administration. Bolstered by unified Democratic control on Capitol Hill, the Administration’s first major legislative initiative was the American Rescue Plan (ARP),92Pub. L. No. 117-2, 135 Stat. 4 (2020).

a third spending bill spurred by the pandemic. Unlike earlier pandemic relief packages, ARP passed through the budget reconciliation process and along party lines.93See Grace Segers & Melissa Quinn, House Approves .9 Trillion COVID Relief Package, Sending Bill to Biden, CBS News (Mar. 11, 2021, 7:01 AM), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/covid-relief-bill-american-rescue-plan-passes-house-representatives [perma.cc/5RBG-E3PQ] (noting passage by a 50–49 vote in the Senate and a 220–211 vote in the House).

The $1.9 trillion package focused on short-term but ambitious federal spending measures.94See White House, The American Rescue Plan, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/American-Rescue-Plan-Fact-Sheet.pdf [perma.cc/8D64-NXA7].

It provided for additional stimulus checks; extended unemployment benefits; expanded assistance to low-income Americans, including Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, child and dependent tax credits, housing assistance, and Affordable Care Act subsidies; and allocated billions in funding for schools, public health, and state and local governments.95See id.

ARP’s proponents celebrated the bill as “the most far-reaching anti-poverty legislation” in decades, with the potential to cut child poverty in half.96See Dylan Matthews, Joe Biden Just Launched the Second War on Poverty, Vox (Mar. 10, 2021, 2:20 PM), https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/22319572/joe-biden-american-rescue-plan-war-on-poverty [perma.cc/H4J9-7FTE].

Despite partisan divisions in Washington, ARP enjoyed broad public support, including from a majority of Republican voters.97See Aaron Rupar, Republicans Shamelessly Take Credit for Covid Relief They Voted Against, Vox (Mar. 15, 2021, 3:40 PM), https://www.vox.com/2021/3/15/22331722/american-rescue-plan-salazar-wicker [perma.cc/5R4F-XYHR].

While the pandemic was an obvious spur to greater federal spending, the Biden Administration also sought to direct spending in pursuit of other policy goals untethered from a particular emergency. It achieved three major bipartisan victories.98The Biden Administration’s major spending-related failure was the proposed “Build Back Better” legislation, which packaged “major initiatives on the economy, education, social welfare, climate change[,] and foreign policy” into a .5 trillion spending bill. Jim Tankersley, Biden’s Entire Presidential Agenda Rests on Expansive Spending Bill, N.Y. Times (Oct. 5, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/18/business/economy/biden-spending-bill.html [perma.cc/TYR2-PJA3]; John Cassidy, Joe Manchin Kills the Build Back Better Bill, New Yorker (Dec. 19, 2021), https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/joe-manchin-kills-the-build-back-better-bill [perma.cc/RDR4-NCMH].

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)99Pub. L. No. 117-58, 135 Stat. 429 (2021).

provided for $550 billion in new spending “to upgrade the nation’s roads, bridges, pipes, ports, broadband and other public works.”100Heather Long, What’s in the .2 Trillion Infrastructure Law, Wash. Post (Nov. 16, 2021, 11:27 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/08/10/senate-infrastructure-bill-what-is-in-it [perma.cc/VT88-5UKE].

The IIJA allocated $550 billion in new investments, including $110 billion for roads and bridges, $55 billion for water infrastructure, and $12.5 billion for electric-vehicle charging stations and zero-emission school buses.101See id.

The CHIPS and Science Act102Pub. L. No. 117-167, 136 Stat. 1366 (2022).

provided $52.7 billion in subsidies for U.S. semiconductor production and an investment tax credit for chip plants, while also authorizing $200 billion over ten years to support scientific research.103David Shepardson & Jeff Mason, Biden Signs Bill to Boost U.S. Chips, Compete with China, Reuters (Aug. 9, 2022, 7:24 PM), https://www.reuters.com/technology/biden-sign-bill-boost-us-chips-compete-with-china-2022-08-09 [perma.cc/BDY9-V4NE].

The Honoring Our PACT Act104Pub. L. No. 117-168, 136 Stat. 1759 (2022).

was the largest expansion of veterans’ benefits in three decades, at a projected cost of $280 billion of mandatory spending over ten years to support veterans harmed by toxic substances during their service.105Stephanie Lai, Senate Passes Bill to Expand Benefits for Veterans Exposed to Burn Pits, N.Y. Times (Aug. 2, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/02/us/politics/senate-burn-pits-veterans.html [perma.cc/8LZP-MWTR].

Perhaps most important, however, was the emergence of spending as Congress’s tool of choice to address the climate crisis. I examine that effort next.

C. Climate Legislation: A Turn to Spending

No context better exemplifies Congress’s shift away from regulatory legislation and toward spending than efforts to fight climate change. After failed attempts to enact regulatory legislation to reduce carbon emissions, supporters of climate action in Congress pivoted toward advocacy for large-scale spending bills that would promote renewable energy and a greener economy. The turn to spending culminated in the enactment of historic 2022 legislation containing clean energy tax credits that analysts estimated may exceed $1 trillion.106See Inflation Reduction Act, Pub. L. No. 117-169, 136 Stat. 1818 (2022); see also David Lawder, U.S. Treasury to Issue More Clean Energy Tax Credit Guidance by Year-End, Reuters (Sept. 8, 2023, 5:03 AM), https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/sustainable-finance-reporting/us-treasury-issue-more-clean-energy-tax-credit-guidance-by-year-end-2023-09-08 [perma.cc/XKT3-XB9S] (noting that “strong demand for the credits from investment projects have prompted some analysts to estimate that the IRA’s fiscal costs could reach trillion,” nearly triple initial estimates).

While the passage of that legislation was seen by many as the culmination of decades-long efforts, it in fact marked a discontinuity: a shift away from regulatory legislation and toward spending in the climate sphere.

For decades, regulatory initiatives were the cornerstones of federal environmental law. The major environmental statutes of the twentieth century are regulatory statutes, setting out requirements binding on private parties and delegating power to administrative agencies to do the same.107See supra note 61 (citing statutes).

In the early twenty-first century, many who were concerned about climate change sought to enact a federal cap-and-trade program, a regulatory scheme that would have set a ceiling on carbon emissions while allowing companies to trade pollution permits, thereby creating a market-based incentive to lower emissions.108See, e.g., Robert N. Stavins, Opinion, Cap and Trade Is the Only Feasible Way of Cutting Emissions, N.Y. Times (June 2, 2014, 1:59 PM), https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2014/06/01/can-the-market-stave-off-global-warming/cap-and-trade-is-the-only-feasible-way-of-cutting-emissions [perma.cc/498X-TTM9].

A Republican president, George H.W. Bush, had earlier signed cap-and-trade legislation for airborne sulfur dioxide pollution, in response to acid rain.109See John M. Broder, ‘Cap and Trade’ Loses Its Standing as Energy Policy of Choice, N.Y. Times (Mar. 25, 2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/26/science/earth/26climate.html [perma.cc/643F-CBQP].

States adopted cap-and-trade programs as part of efforts to control carbon emissions.110See, e.g., Cap-and-Trade Program: About, Cal. Air Res. Bd., https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/cap-and-trade-program/about [perma.cc/97Q3-DDK9].

Congress considered bipartisan cap-and-trade bills several times during the early 2000s, but such efforts never resulted in the enactment of legislation.111See, e.g., American Clean Energy and Security Act, H.R. 2454, 111th Cong. (2009); Climate Stewardship Act, S. 139, 108th Cong. (2003).

Senate procedure and changing politics combined to doom Congress’s efforts to enact cap-and-trade legislation. The closest that a cap-and-trade bill came to becoming law was the American Clean Energy and Security Act,112H.R. 2454, supra note 111.

which passed the House in 2010 but was never brought to the Senate floor. The proximate cause was Senate rules: The bill’s proponents were simply unable to garner the sixty votes needed to break an anticipated Senate filibuster.113Ryan Lizza, As the World Burns, New Yorker (Oct. 3, 2010), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/11/as-the-world-burns [perma.cc/4RPH-QLEN] (“[I]f there weren’t sixty votes to pass the bill in the Senate, the White House would not expend much effort on the matter.”).

The Senate’s supermajority cloture threshold nearly always necessitates bipartisanship, which is challenging given political polarization, and also lowers the number of senators who industry opponents must persuade to oppose a bill.114Cf. Elaine Kamarck, The Challenging Politics of Climate Change, Brookings

(Sept. 23, 2019), https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-challenging-politics-of-climate-change [perma.cc/MW82-P585] (discussing the challenges of climate change legislation).

Further, though some conservatives had previously supported cap-and-trade policies, many came to brand them an “economy-killing tax,” which in turn made regulatory initiatives aimed at curbing emissions using market incentives a political third rail.115Broder, supra note 109; Darren Samuelsohn, Cap-and-Trade Policies Losing Steam, Politico (July 8, 2011, 8:25 AM), https://www.politico.com/story/2011/07/cap-and-trade-policies-losing-steam-058559 [perma.cc/T65T-LN4W]. Similar political challenges have doomed efforts to enact a carbon tax, another market-based policy designed to address climate change that once had some conservative support. See Robinson Meyer, Carbon Tax, Beloved Policy to Fix Climate Change, Is Dead at 47, Atlantic (July 20, 2021), https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2021/07/obituary-carbon-tax-beloved-climate-policy-dies-47/619507 [perma.cc/XT5J-Y2L9] (discussing political impediments to enacting a carbon tax).

In contrast, the political conditions for spending measures to address climate change are considerably more favorable. Senate rules allow Congress to spend on climate-related matters without facing a Senate filibuster.116See infra Section II.A.

Politically, spending money to promote greener sources of energy does not raise energy costs for consumers and in some instances even lowers them.117Rachel Koning Beals, State of the Union: Biden Tells Congress to Revive EV, Clean-Energy Incentives to Control Inflation, Save Households 0 a Year, MarketWatch (Mar. 2, 2022, 9:49 AM), https://www.marketwatch.com/story/biden-revive-ev-clean-energy-incentives-to-help-control-inflation-save-families-500-a-year-11646188975 [perma.cc/7PVW-9KPU] (quoting President Joe Biden’s prediction that making electric vehicles more affordable would save families “ a month”).

Further, because climate-related spending can provide concentrated economic benefits to industry, a climate spending package has natural allies in producers of solar, wind, and other renewable energy sources.118See Todd Woody, Solar Industry Takes on Coal and Oil Lobbies, N.Y. Times: Green (Oct. 27, 2009, 2:02 PM), https://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/10/27/solar-industry-takes-on-coal-and-oil-lobbies [perma.cc/68XC-52QU] (describing the solar industry’s call for increased lobbying, as well as the “slew of tax breaks, incentives and loan guarantees” the solar industry had won in the past year); see also infra note 210 (describing lobbying by clean energy industry groups).

And fossil fuel companies are less likely to oppose subsidies for renewable energy than they are to oppose climate regulation. Subsidies for renewables pose a less direct threat to fossil fuel company profits and can even benefit such firms if they have investments in renewables alongside their core fossil fuel business.119The degree of investment has varied considerably across firms. See Clifford Krauss, U.S. and European Oil Giants Go Different Ways on Climate Change, N.Y. Times (Oct. 13, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/21/business/energy-environment/oil-climate-change-us-europe.html [perma.cc/6QUH-XMYQ].

As one commentator noted, “by mostly focusing on financial rewards rather than punitive regulations,” advocates argue that climate spending “could build crucial political support among businesses and industries in the years to come.”120Jeff Tollefson, What Biden’s -Trillion Spending Bill Could Mean for Climate Change, Nature (Dec. 17, 2021), https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03787-7 [perma.cc/TYZ7-QB2E]; see also Danny Cullenward & David G. Victor, Making Climate Policy Work 180–81 (2020) (describing the question of “will incumbent firms and industry associations be part of the political problem, or part of the solution?” as “one of the most important political challenges in deep decarbonization”).

These dynamics help to explain why supporters of climate action in Congress shifted their focus toward spending. The Green New Deal called for spending on transportation and infrastructure to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, but it made no mention of cap and trade.121See H. Res. 109, 116th Cong. (2019) (calling for public investment in research and development of renewable energy, as well as investments in zero-emission vehicle infrastructure and manufacturing, public transit, and high-speed rail).

Progressive advocates argued that public investments made through budget reconciliation are key to climate policy.122See Trevor Higgins, Budget Reconciliation Is the Key to Stopping Climate Change, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Aug. 16, 2021), https://www.americanprogress.org/article/budget-reconciliation-key-stopping-climate-change [perma.cc/42AS-RRUF] (noting that reconciliation can be used to create incentives for clean energy and clean vehicles, investments in greener agriculture and forestry practice, and rebates for home electrification, among other investments).

Climate spending was central to the proposed Build Back Better bill, with more than half a trillion dollars dedicated to clean energy incentives and tax credits.123Denise Chow & Evan Bush, Billions and Trillions: Climate Efforts Set for Big Boost if Build Back Better Bill Passes, NBC News (Nov. 28, 2021, 7:33 AM), https://www.nbcnews.com/science/environment/climate-change-efforts-set-big-boost-build-back-better-bill-passes-rcna6471 [perma.cc/6D4D-LW3S].

Commentators noted that this spending-focused approach to climate represented a strategic shift away from the historic focus on regulation as the best means for Congress to fight climate change.124See, e.g., Tollefson, supra note 120 (describing “a strategic shift” from cap-and-trade legislation to “large government investments to curb emissions by driving down the cost of low-carbon technologies, creating new industries and jobs, and bolstering US competitiveness abroad”).

This shift in strategy bore fruit with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.125Pub. L. No. 117-169, 136 Stat. 1818.

The law was hailed as “the most ambitious action ever taken by the United States to try to stop the planet from catastrophically overheating.”126Lisa Friedman & Brad Plumer, Surprise Deal Would Be Most Ambitious Climate Action Undertaken by U.S., N.Y. Times (July 28, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/28/climate/climate-change-deal-manchin.html [perma.cc/ZP43-NGFB].

It included tax incentives to encourage consumers to purchase electric vehicles, financial inducements for electric utilities to pivot toward using renewable energy sources like wind or solar power, funds for oil companies that reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, and funds to spur development of green technologies.127See Ben Lefebvre, Kelsey Tamborrino & Josh Siegel, Historic Climate Bill to Supercharge Clean Energy Industry, Politico (Aug. 7, 2022, 4:53 PM), https://www.politico.com/news/2022/08/07/inflation-reduction-act-climate-biden-00050230 [perma.cc/K2ZX-37TC].

All told, the value of these incentives is expected to exceed $1 trillion.128See supra note 108 and accompanying text.

To be sure, implementing these programs requires administrative policymaking by federal and state agencies, but the use of carrots (largely tax credits) rather than sticks was key to the law’s passage. Its reliance on spending prompted less opposition from the fossil fuel industry, with one former senator characterizing the bill as an “easier [political] lift” because it was “all incentives.”129Maxine Joselow, Why the Inflation Reduction Act Passed the Senate but Cap-and-Trade Didn’t, Wash. Post: Climate 202 (Aug. 10, 2022, 8:10 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/08/10/why-inflation-reduction-act-passed-senate-cap-and-trade-didnt [perma.cc/ZJ7Q-SGDW] (quoting former Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-CA)). Independent of politics, there are also policy advantages to a spending-based approach. See Cullenward & Victor, supra note 120, at 176 (“Pushing early-stage technologies requires efforts tailored to each sector—something that is hard to do with market-based instruments that cover all sectors with a single carbon price determined by the opposition of the most entrenched sector.”).

* * *

Taken together, this recent history shows a clear pattern: Congress has slowed its pace of regulatory lawmaking, while passing some record-high spending measures. This change matters for both policy outcomes and the performance of our governing institutions. Before evaluating the trend, however, the next Part examines why it has occurred.

II. Why a Republic of Spending?

Why has Congress continued to spend money, often in historically large amounts, even as its productivity in enacting regulatory statutes has declined? One answer is that some policy goals require public spending: Congress has little choice but to appropriate funds if it wants to create and sustain a social safety net, maintain the military, or improve national infrastructure. But the necessity of spending for policymaking is only part of the story. Four other forces incentivize legislators to prioritize spending over regulatory legislation. First is legislative procedure, especially Senate rules that favor spending over regulation. Second, changes in the two major political parties create a political environment much more favorable to spending than regulation. Third, a collection of public choice dynamics can prompt Congress to pursue spending over regulatory legislation, although the longstanding character of public choice dynamics does not explain the turn toward spending rather than regulatory legislation over time. Fourth, constitutional doctrine is more deferential toward congressional spending choices than toward regulatory legislation, and that asymmetry may widen in the future. These forces are of course closely intertwined—procedural rules are products of party politics and public choice dynamics, for example—but it is helpful to consider them individually to see the multiple currents all pushing toward spending over regulatory legislation.

A. Bifurcated Legislative Procedure

Congress’s procedural rules make it easier to spend than to enact regulatory legislation. The Senate’s cloture rule, Rule XXII, requires a supermajority vote in order to close debate and move to a final vote on ordinary legislation.130See Standing Rules of the Senate, r. XXII(2), S. Doc. No. 113-18 (2013), https://rules.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/CDOC-113sdoc18.pdf [perma.cc/KL36-4VCZ].

Since 1975, that rule has required the assent of three-fifths of senators duly chosen and sworn in order to close debate, which equates to sixty senators when all Senate seats are filled.131Rule XXII previously required a two-thirds supermajority to close debate, and prior to 1917 the Senate’s rules contained no mechanism for closing debate. See Gregory J. Wawro & Eric Schickler, Filibuster: Obstruction and Lawmaking in the U.S. Senate 89 (2006).

In the nearly half-century that the contemporary cloture rule has been in effect, Republicans have never held sixty Senate seats, and Democrats have done so only briefly.132Party Division, U.S. Senate, https://www.senate.gov/history/partydiv.htm [perma.cc/P97W-ZNNB] (noting Democratic sixty-vote majorities for four years in the late 1970s and for roughly one year in 2009–10). On the importance of the close divisions in the modern Congress, see generally Morris P. Fiorina, Unstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political Stalemate (2017); Frances E. Lee, Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign (2016).

The sixty-vote cloture requirement has therefore almost always functioned as a de facto bipartisanship requirement, preventing the majority party from closing debate on legislation without the support of some minority party members.

Polarization in Congress in the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries made the supermajority cloture requirement a major cause of legislative gridlock. During that period, congressional Republicans became significantly more conservative and congressional Democrats became somewhat more liberal.133See Nolan McCarty, What We Know and Don’t Know About Our Polarized Politics, in Political Polarization in American Politics 1, 3 (Daniel J. Hopkins & John Sides eds., 2015) (describing the asymmetry in polarization between the parties).

With the parties sharply divided, the cloture rule allows a unified minority party to block legislation favored by the majority party. Polarized parties use the filibuster far more frequently than in earlier, less-polarized eras,134See Jacob S. Hacker & Paul Pierson, American Amnesia 329–30 (2016) (collecting statistics on the increasing prevalence of the filibuster).

leading bills to fail even when they have the strong support of the White House, a majority of the House, and a majority (but not a supermajority) of the Senate.135The failure of the DREAM Act provides a high-profile example. See Roll Call Vote 11th Congress—2nd Session: On the Cloture Motion (Motion to Invoke Cloture on the Motion to Concur in the House Amendment to the Senate Amendment No. 3 to H.R. 5281), U.S. Senate (Dec. 18, 2010), https://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_votes/vote1112/vote_111_2_00278.htm [perma.cc/2B3Q-9GA5] (reporting failure to invoke cloture despite 55 yea votes).

The cloture rule, combined with partisan divisions and widespread use of the filibuster, means that the only high-profile legislation subject to the filibuster that can pass in the contemporary Congress are bipartisan measures. The limits on legislative action imposed by the cloture rule led many to condemn the rule as a major cause of congressional gridlock.136See, e.g., McCarty, supra note 1, at 232–34; Daniel Wirls, Of Rules and Representation (and Dysfunction) in the United States Senate, 51 Tulsa L. Rev. 373 (2016).

The difficulty of garnering sixty votes to close debate in the Senate has led the body to create exceptions to the sixty-vote threshold.137See Molly E. Reynolds, Exceptions to the Rule: The Politics of Filibuster Limitations in the U.S. Senate 2 (2017) (defining “majoritarian exceptions” to Senate rules as “special procedures [to] empower simple majorities and make operations of the Senate more majoritarian”).

The most important of the Senate’s majoritarian exceptions is the budget reconciliation process.138See id. at 81–92 (describing the origins of budget reconciliation in the 1970s and its early history).

The choreography of the reconciliation process is elaborate, but its most salient feature is that it allows the Senate to close debate on some spending or tax measures with a simple majority vote.139See id. at 90 (describing how reconciliation sets time limits on floor debate and restricts amending activity).

Critically, however, the reconciliation process is limited to legislation relating to spending and taxation—not regulation. This limitation is set out in the Byrd rule,1402 U.S.C. § 644.

which, roughly speaking, distinguishes between revenue-related provisions, which are allowed under reconciliation, and regulatory provisions, which are not.141Id. § 644(b)(1)(D) (“[A] provision shall be considered extraneous if it produces changes in outlays or revenues which are merely incidental to the non-budgetary components of the provision.”).

This line is notoriously difficult to apply in practice, and the parties frequently disagree about whether a given provision may be included in a reconciliation bill.142For discussions of how the Byrd rule is applied in practice, see Ellen P. Aprill & Daniel J. Hemel, The Tax Legislative Process: A Byrd’s Eye View, 81 Law & Contemp. Probs. 99 (2018), and Jonathan S. Gould, The Senate’s Shadow Doctrine, 61 Harv. J. on Legis. 317 (2024).

To simplify, however, the Byrd rule forecloses major changes to regulatory law through reconciliation, even if those changes impact the federal fisc. The Byrd rule has impeded both parties’ attempts to include regulatory changes in reconciliation bills: It tied Republicans’ hands during their efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act in the late 2010s,143See Amber Phillips, The Budget Rule You’ve Never Heard of that Ties Republicans’ Hands on Obamacare, Wash. Post (Mar. 9, 2017, 10:45 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/03/09/the-budget-rule-youve-never-heard-of-that-ties-republicans-hands-on-obamacare [perma.cc/M53F-U9PN].

and it stopped Democrats from raising the minimum wage in 2021.144See Emily Cochrane, Top Senate Official Disqualifies Minimum Wage from Stimulus Plan, N.Y. Times (Sept. 10, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/25/us/politics/federal-minimum-wage.html [perma.cc/PB56-KDG8].

The reconciliation process has shaped the legislative agendas of presidents of both parties. The first Trump Administration’s signature legislative accomplishment, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,145Pub. L. No. 115-97, 131 Stat. 2054 (2017).

passed through reconciliation, on party lines and with a bare majority.146See Thomas Kaplan & Alan Rappeport, Republican Tax Bill Passes Senate in 51–48 Vote, N.Y. Times (Dec. 19, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/19/us/politics/tax-bill-vote-congress.html [perma.cc/VSF8-NV4C].

Its other major legislative effort, an unsuccessful attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act, was likewise pursued through reconciliation.147See Timothy Jost, Senate Approves Reconciliation Bill Repealing Large Portions of ACA (Updated), Health Affs. (Dec. 4, 2015), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20151204.052111/full [perma.cc/7R8G-G5ZU].